The Future of Squaw Valley and Alpine Meadows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games Pyeongchang 2018 English

English The Olympic&Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 Welcome to Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 PyeongChang 2018! days February PyeongChang 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games will take place in 17 / 9~25 PyeongChang, Gangneung and Jeongseon for 27 days in Korea. Come and watch the disciplines medal events new records, new miracles, and new horizons unfolding in PyeongChang. 15 102 95 countries 2 ,900athletes Soohorang The name ‘Soohorang’ is a combinati- on of several meanings in the Korean language. ‘Sooho’ is the Korean word for ‘protection’, meaning that it protects the athletes, spectators and all participants of the Olympic Games. ‘Rang’ comes from the middle letter of ‘ho-rang-i’, which means ‘tiger’, and also from the last letter of ‘Jeongseon Arirang’, a traditional folk music of Gangwon Province, where the host city is located. Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 10 days/ 9~18 March 6 disciplines 80 medal events 45 countries 670 athletes Bandabi The bear is symbolic of strong will and courage. The Asiatic Black Bear is also the symbolic animal of Gangwon Province. In the name ‘Bandabi’, ‘banda’ comes from ‘bandal’ meaning ‘half-moon’, indicating the white crescent on the chest of the Asiatic Black Bear, and ‘bi’ has the meaning of celebrating the Games. VISION PyeongChang 2018 will begin the world’s greatest celebration of winter sports from 9 February 2018 in PyeongChang, Gangneung, New Horizons and Jeongseon. People from all corners of the PyeongChang 2018 will open the new horizons for Asia’s winter sports world will gather in harmony. PyeongChang will and leave a sustainable legacy in PyeongChang and Korea. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

2011-Summer.Pdf

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE VOL. 82 NO. 2 SUMMER 2011 BV O L . 8 2 N Oow . 2 S UMMER 2 0 1 1 doin STANDP U WITH ASOCIAL FOR THECLASSOF1961, BOWDOINISFOREVER CONSCIENCE JILLSHAWRUDDOCK’77 HARI KONDABOLU ’04 SLICINGTHEPIEFOR THE POWER OF COMEDY AS AN STUDENTACTIVITIES INSTRUMENT FOR CHANGE SUMMER 2011 CONTENTS BowdoinMAGAZINE 24 AGreatSecondHalf PHOTOGRAPHS BY FELICE BOUCHER In an interview that coincided with the opening of an exhibition of the Victoria and Albert’s English alabaster reliefs at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last semester, Jill Shaw Ruddock ’77 talks about the goal of her new book, The Second Half of Your Life—to make the second half the best half. 30 FortheClassof1961,BowdoinisForever BY LISA WESEL • PHOTOGRAHS BY BOB HANDELMAN AND BRIAN WEDGE ’97 After 50 years as Bowdoin alumni, the Class of 1961 is a particularly close-knit group. Lisa Wesel spent time with a group of them talking about friendship, formative experi- ences, and the privilege of traveling a long road together. 36 StandUpWithaSocialConscience BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY KARSTEN MORAN ’05 The Seattle Times has called Hari Kondabolu ’04 “a young man reaching for the hand-scalding torch of confrontational comics like Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor.” Ed Beem talks to Hari about his journey from Queens to Brunswick and the power of comedy as an instrument of social change. 44 SlicingthePie BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY DEAN ABRAMSON The Student Activity Fund Committee distributes funding of nearly $700,000 a year in support of clubs, entertainment, and community service. -

June 21, 2017 Purpose: Update the Board Of

June21,2017 Purpose:UpdatetheBoardofDirectorsontheprocessofhiringamasterplanconsultantforthe downhillskiareaatTahoeDonnerAssociation. Background: Tahoe Donner’s current Downhill Ski Lodge was built by DART in 1970, with subsequent additions and remodels through the last 45 years, attempting to accommodate growingvisitationnumbersandservicelevels.Afewyearsago,theGeneralPlanCommittee’s DownhillSkiAreaSubͲgroupworkedtoprovideacomprehensive2013report,includinganalysis ofthefollowingmetricsoftheDownhillSkiOperations,seeattached; OnAugust6,2016,Aprojectinformationpaper(PIP)wasprovidedtotheBoardofDirectors,and duringthe2016BudgetProcess,a$50KDevelopmentFundbudgetwasidentifiedandapproved bytheBoardofDirectorsforexpenditurein2017.OnNovember10,2016,TheGPCinitiateda TaskForcetoregainthe2013momentum,toidentifyanddetailfurtheropportunitiesatthe DownhillSkiArea.InAprilof2017,theTaskForcereceivedapprovaltoproceedwiththeRFP processtosolicittwoindustryleaderswithexperienceinskiareamasterplanning,seeattached SOQ’s. Discussion: 1. BothconsultantsprovidedfeeproposalsbythedeadlineofJune16th.Afterqualifying bothproposals,bothwerethoroughandwellmatched,bothwithpositivereferences. 2. BothfeeproposalsarewithintheBoardapproved$50KDFbudgetfor2017. 3. Furtherclarificationsandquestionsarecurrentlyunderwaywithbothconsultants,so thatscoringresultsandweightingcanbefinalizedandtallied.Ifacontractcanbe executedinearlyJuly,thedraftreportcouldbeavailableandpresentedatthe SeptemberGPCMeeting,whichwouldreflectnearly80%ofthecontentinfinalreport. 4. Oncefeedbackisprovided,thefinalversionwouldbecompletedwithinsixweeks. -

Ski Resorts (Canada)

SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] ALBERTA • WinSport's Canada Olympic Park (1988 Winter Olympics • Canmore Nordic Centre (1988 Winter Olympics) • Canyon Ski Area - Red Deer • Castle Mountain Resort - Pincher Creek • Drumheller Valley Ski Club • Eastlink Park - Whitecourt, Alberta • Edmonton Ski Club • Fairview Ski Hill - Fairview • Fortress Mountain Resort - Kananaskis Country, Alberta between Calgary and Banff • Hidden Valley Ski Area - near Medicine Hat, located in the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park in south-eastern Alberta • Innisfail Ski Hill - in Innisfail • Kinosoo Ridge Ski Resort - Cold Lake • Lake Louise Mountain Resort - Lake Louise in Banff National Park • Little Smokey Ski Area - Falher, Alberta • Marmot Basin - Jasper • Misery Mountain, Alberta - Peace River • Mount Norquay ski resort - Banff • Nakiska (1988 Winter Olympics) • Nitehawk Ski Area - Grande Prairie • Pass Powderkeg - Blairmore • Rabbit Hill Snow Resort - Leduc • Silver Summit - Edson • Snow Valley Ski Club - city of Edmonton • Sunridge Ski Area - city of Edmonton • Sunshine Village - Banff • Tawatinaw Valley Ski Club - Tawatinaw, Alberta • Valley Ski Club - Alliance, Alberta • Vista Ridge - in Fort McMurray • Whispering Pines ski resort - Worsley British Columbia Page 1 of 8 SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] • HELI SKIING OPERATORS: • Bearpaw Heli • Bella Coola Heli Sports[2] • CMH Heli-Skiing & Summer Adventures[3] • Crescent Spur Heli[4] • Eagle Pass Heli[5] • Great Canadian Heliskiing[6] • James Orr Heliski[7] • Kingfisher Heli[8] • Last Frontier Heliskiing[9] • Mica Heliskiing Guides[10] • Mike Wiegele Helicopter Skiing[11] • Northern Escape Heli-skiing[12] • Powder Mountain Whistler • Purcell Heli[13] • RK Heliski[14] • Selkirk Tangiers Heli[15] • Silvertip Lodge Heli[16] • Skeena Heli[17] • Snowwater Heli[18] • Stellar Heliskiing[19] • Tyax Lodge & Heliskiing [20] • Whistler Heli[21] • White Wilderness Heli[22] • Apex Mountain Resort, Penticton • Bear Mountain Ski Hill, Dawson Creek • Big Bam Ski Hill, Fort St. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

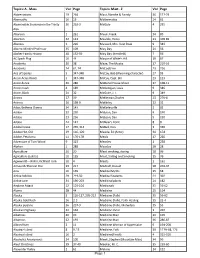

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Master's Degree Thesis

Master’s degree thesis IDR950 Sport Management “Marketing Mountains for the future of Geilo”: Co-creating value by including stakeholders in the sustainable development process of a ski resort Benjamin Moeyersons Number of pages including this page: 100 Molde, 14/05/2018 Mandatory statement Each student is responsible for complying with rules and regulations that relate to examinations and to academic work in general. The purpose of the mandatory statement is to make students aware of their responsibility and the consequences of cheating. Failure to complete the statement does not excuse students from their responsibility. Please complete the mandatory statement by placing a mark in each box for statements 1-6 below. 1. I/we hereby declare that my/our paper/assignment is my/our own work, and that I/we have not used other sources or received other help than mentioned in the paper/assignment. 2. I/we hereby declare that this paper Mark each 1. Has not been used in any other exam at another box: department/university/university college 1. 2. Is not referring to the work of others without acknowledgement 2. 3. Is not referring to my/our previous work without acknowledgement 3. 4. Has acknowledged all sources of literature in the text and in the list of references 4. 5. Is not a copy, duplicate or transcript of other work 5. I am/we are aware that any breach of the above will be considered as cheating, and may result in annulment of the examination and 3. exclusion from all universities and university colleges in Norway for up to one year, according to the Act relating to Norwegian Universities and University Colleges, section 4-7 and 4-8 and Examination regulations section 14 and 15. -

Bear Creek Watershed Assessment Report

BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT PLACER COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Prepared by: PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96162 February 16, 2018 And Dr. Susan Lindstrom, PhD BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA February 16, 2018 A REPORT PREPARED FOR: Truckee River Watershed Council PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96161 (530) 550-8760 www.truckeeriverwc.org by Brian Hastings Balance Hydrologics Geomorphologist Matt Wacker HT Harvey and Associates Restoration Ecologist Reviewed by: David Shaw Balance Hydrologics Principal Hydrologist © 2018 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. Project Assignment: 217121 800 Bancroft Way, Suite 101 ~ Berkeley, California 94710-2251 ~ (510) 704-1000 ~ [email protected] Balance Hydrologics, Inc. i BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA < This page intentionally left blank > ii Balance Hydrologics, Inc. BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Goals and Objectives 1 1.2 Structure of This Report 4 1.3 Acknowledgments 4 1.4 Work Conducted 5 2 BACKGROUND 6 2.1 Truckee River Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) 6 2.2 Water Resource Regulations Specific to Bear Creek 7 3 WATERSHED SETTING 9 3.1 Watershed Geology 13 3.1.1 Bedrock Geology and Structure 17 3.1.2 Glaciation 18 3.2 Hydrologic Soil Groups 19 3.3 Hydrology and Climate 24 3.3.1 Hydrology 24 3.3.2 Climate 24 3.3.3 Climate Variability: Wet and Dry Periods 24 3.3.4 Climate Change 33 3.4 Bear Creek Water Quality 33 3.4.1 Review of Available Water Quality Data 33 3.5 Sediment Transport 39 3.6 Biological Resources 40 3.6.1 Land Cover and Vegetation Communities 40 3.6.2 Invasive Species 53 3.6.3 Wildfire 53 3.6.4 General Wildlife 57 3.6.5 Special-Status Species 59 3.7 Disturbance History 74 3.7.1 Livestock Grazing 74 3.7.2 Logging 74 3.7.3 Roads and Ski Area Development 76 4 WATERSHED CONDITION 81 4.1 Stream, Riparian, and Meadow Corridor Assessment 81 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. -

TAS References-List 15 06 2018

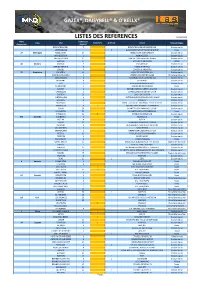

GAZEX®, DAISYBELL ® & O'BELLX ® LISTES DES REFERENCES 15/06/2018 Nbre Exploseurs Pays Site DAISYBELL O'BELLX Client Sites protégés d'appareils GAZEX® BERCHTESGADEN 7 BERCHTESGADENER BERGBAHN Station de ski MITTENWALD 2 WASSERWIRTSCHAFTSAMT WILHEIM Route 27 Allemagne NEBELHORN 17 NEBELHORN OBERSTDORF Station de ski WENDELSTEIN 1 WENDELSTEIN Station de ski PAS DE LA CASA 15 SAETDE / SAS Porte des Neiges Station de ski ARINSAL 13 GOVERN D'ANDORRA Village 46 Andorre ARINSAL 3 PAL ARINSAL Station de ski ORDINO ARCALIS 8 COMU D'ORDINO Station de ski SOLDEU 7 GOVERN D'ANDORRA Station de ski 15 Argentine LAS LEÑAS 12 VALLE DE LAS LEÑAS S.A. Station de ski BARRICK VELADERO 3 MINERA ARGENTINA GOLD Mine/Site industriel AUSSERGOLM 4 VORARLBERGER LLLWERKE AG Station de ski BERWANG 4 BERWANG Station de ski FISS 7 FISSER BERGBAHNEN / FISS Station de ski FUGENBERG 4 GEMEINDE FÜGENBERG Route GALTÜR 2 BERGBAHNEN SILVRETTA GALTÜR Station de ski GARGELLEN 5 GARGELLENER SEILBAHN GmbH Station de ski GASTEIN 20 1 BAD HOFGASTEIN Station de ski HINTERGLEM 9 HINTERGLEMMER BERGBAHNEN GMBH Station de ski HOCHOTZ 4 HOCHOTZ Station de ski HOCHSOLL 5 BERG- und SKILIFT HOCHSÖLL Gmbh & co KG Station de ski INNSBRUCk 4 1 INNSBRUCKER NORDKETTENBAHNEN Station de ski ISCHGL 36 SILVRETTA SEILBAHN AG / ISCHGL Station de ski KAUNERTAL 20 KAUNERTALER GLETSCHERBAHN Route KITZBÜHEL 12 1 KITZBUHEL BERGBAHN Station de ski 375 Autriche KLEINSOLK 2 KLEINSOLK Route KUTHAI 4 KUTHAI Station de ski LOSER 11 GEMEINDE ALTAUSSEE / LOSER Station de ski NAUDERS 4 BERGBAHNEN NAUDERS / NAUDERS Station de ski NEUKIRCHEN 4 NEUKIRCHEN Station de ski OBERTAUERN 2 OBERTAUERN SEILBAHN GmbH Station de ski PITZTAL 10 PiITZALER GLETSCHERBAHNEN Station de ski RIEZLERN 2 KANZELWAND Station de ski SAALFELDEN 3 LAND SALZBURG Route SANKT ANTON 65 ARLBERGER BERGBAHNEN / St. -

Eco Brochure for Website1.Cdr

Mountain Resort Planners Ltd. President’s Message EcosignMountainResortPlannersLtd.wasformedin1975withasingle corporatemission: Design the most efficient, humanly pleasing mountain resorts in the world. We remain committed to accomplishing this goal through the use of sensitive design practices and high technology tools that allow us to create resorts that carefully balance human activity with the surroundingnaturalenvironment. Ecosign has firmly established itself as a world leader in the design of successful,awardwinningandprofitablemountainresorts. Creative . innovative and courageous are words used by our clients to describe our services and design solutions. All of Ecosign’s professionals possess these qualities and remain passionate about assisting our clients in these dynamic and challenging times for the resortbusiness. PAUL E. MATHEWS President Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners Ltd. General Information Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners Ltd. (”Ecosign”) is the world’s most experienced mountain resort planning firmwithsuccessfulprojectexperiencespanningsixcontinents. Ecosign provides a wide range of consulting services including: ski area design, resort planning, urban design, landscape architecture, market and financial analysis, resort operations and environmental assessment. We have the expertise to assist at any stage of the resort development process whether it is introducing new industry technology to an existing resort or evaluating the feasibility of creating a new resort. In consultation with the client, Ecosign establishes -

On Arriving at Snake River They Commenced at Once to Build a Fort

quarterlyoverland of the oregon-california trails association journalvolume 34 · number 1 · spring 2016 On arriving at Snake river they commenced at once to build a fort. quarterlyoverland of the oregon-california trails association journalvolume 34 · number 1 · spring 2016 John Winner President The Oregon-California Trails Association Pat Traffas Vice President Marvin Burke Treasurer P.O. Box 1019 · Independence, mo 64051 Sandra Wiechert Secretary www.octa-trails.org · (816) 252-2276 · [email protected] Jere Krakow Preservation Officer John Krizek Past President preserving the trails F. Travis Boley Association Manager octa’s membership and volunteer leadership seek to preserve our heritage. Our Kathy Conway Headquarters Manager accomplishments include: Marlene Smith-Baranzini · Purchasing Nebraska’s “California Hill,” with ruts cut by emigrant wagons as they climbed Overland Journal Editor from the South Platte River. Ariane C. Smith Design & production · Protecting emigrant graves. · Initiating legislation designating the California and Santa Fe trails as National Historic trails. board of directors Cecilia Bell · Persuading government and industry to relocate roads and pipe lines to preserve miles of Don Hartley pristine ruts. Duane Iles Jere Krakow conventions and field trips Our annual convention is held in a different location with proximity to a historical area each Matt Mallinson Dick Nelson August. Convention activities include tours and treks, papers and presentations, meals and Vern Osborne socials, and a display room with book dealers, publishers, and other materials. Loren Pospisil Local chapters also plan treks and activities throughout the year. Bill Symms publications Overland Journal—Issued four times each year, O.J. contains new research and publications committee re-examinations of topics pertaining to the history of the American West, especially the William Hill, Chair Camille Bradford development and use of the trails. -

Travel the Usa: a Reading Roadtrip Booklist

READING ROADTRIP USA TRAVEL THE USA: A READING ROADTRIP BOOKLIST Prepared by Maureen Roberts Enoch Pratt Free Library ALABAMA Giovanni, Nikki. Rosa. New York: Henry Holt, 2005. This title describes the story of Alabama native Rosa Parks and her courageous act of defiance. (Ages 5+) Johnson, Angela. Bird. New York: Dial Books, 2004. Devastated by the loss of a second father, thirteen-year-old Bird follows her stepfather from Cleveland to Alabama in hopes of convincing him to come home, and along the way helps two boys cope with their difficulties. (10-13) Hamilton, Virginia. When Birds Could Talk and Bats Could Sing: the Adventures of Bruh Sparrow, Sis Wren and Their Friends. New York: Blue Sky Press, 1996. A collection of stories, featuring sparrows, jays, buzzards, and bats, based on African American tales originally written down by Martha Young on her father's plantation in Alabama after the Civil War. (7-10) McKissack, Patricia. Run Away Home. New York: Scholastic, 1997. In 1886 in Alabama, an eleven-year-old African American girl and her family befriend and give refuge to a runaway Apache boy. (9-12) Mandel, Peter. Say Hey!: a Song of Willie Mays. New York: Hyperion Books for Young Children, 2000. Rhyming text tells the story of Willie Mays, from his childhood in Alabama to his triumphs in baseball and his acquisition of the nickname the "Say Hey Kid." (4-8) Ray, Delia. Singing Hands. New York: Clarion Books, 2006. In the late 1940s, twelve-year-old Gussie, a minister's daughter, learns the definition of integrity while helping with a celebration at the Alabama School for the Deaf--her punishment for misdeeds against her deaf parents and their boarders.