The Cost of Making Disciples Walter Huffman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 23, Session 2 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship

Unit 23, Session 2 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship Summary and Goal In this session, we will learn about how our commitment to discipleship needs to start on the inside: with a heart and a mind that clearly understand that Jesus requires total submission from us and that submission is costly. It is no light thing to commit our lives to Christ; it isn’t something we can do halfway. But if we understand the immeasurable worth of Jesus’ commitment toward His disciples, we will be motivated to submit ourselves fully to Him. Session Outline 1. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a clear commitment (Luke 9:57-62). 2. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a total commitment (Luke 14:25-27). 3. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a costly commitment (Luke 14:28-35). Background Passages: Luke 9:57-62; 14:25-35 Session in a Sentence 2 Jesus shared that discipleship involves a clear, total, and costly commitment to following Him. Christ Connection Jesus taught that being His disciple comes at a cost. To be His disciple requires a clear and total commitment and will involve sacrifice. When we commit our entire lives to Jesus as His disciples, we emulate the One who laid down His life on our behalf for our salvation. Missional Application Because Jesus sacrificed His life on our behalf to provide our salvation, we seek to commit our time, resources, and energy for the work of sharing Christ with others so they too might be saved. 66 Date of My Bible Study: ______________________ © 2020 LifeWay Christian Resources Group Time GROUP MEMBER CONTENT Introduction EXPLAIN: Use the paragraphs in the DDG (p. -

Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship

Unit .23 Session .02 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship Scripture Luke 9:57-62; 14:25-35 57 As they were going along the road, someone said and come after me cannot be my disciple. 28 For which to him, “I will follow you wherever you go.” 58 And of you, desiring to build a tower, does not first sit down Jesus said to him, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air and count the cost, whether he has enough to complete have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his it? 29 Otherwise, when he has laid a foundation and head.” 59 To another he said, “Follow me.” But he said, is not able to finish, all who see it begin to mock him, “Lord, let me first go and bury my father.” 60 And Jesus 30 saying, ‘This man began to build and was not able said to him, “Leave the dead to bury their own dead. to finish.’31 Or what king, going out to encounter But as for you, go and proclaim the kingdom of God.” another king in war, will not sit down first and deliberate 61 Yet another said, “I will follow you, Lord, but let me whether he is able with ten thousand to meet him who first say farewell to those at my home.”62 Jesus said comes against him with twenty thousand? 32 And if to him, “No one who puts his hand to the plow and not, while the other is yet a great way off, he sends a looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.” …25 Now delegation and asks for terms of peace. -

Lecture Writeup on Bonhoeffer for Discovery 6-14-15

An ‘Ancient’ In Evil Days: Dietrich Bonhoeffer by J. Chester! Johnson Discovery;Trinity Wall Street June 14, 2015; New York, N. Y. ! WE WILL BE EXPLORING THIS MORNING ONE OF THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL, ONE OF THE MOST COMPLEX SPIRITUAL, CHURCH (IN THE BROADER SENSE) FIGURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY: DIETRICH BONHOEFFER, A DEVOTED PACIFIST WHO HELPED ORGANIZE ASSASSINATION ATTEMPTS AGAINST ADOLPH HITLER; BONHOEFFER, A DEVOTED CHRISTIAN WHO BELIEVED UNWAVERINGLY IN TRANSPARENT TRUTH, WHO ALSO WORKED AS A DOUBLE AGENT – A SPY, IF YOU WILL – PROVIDING INFORMATION TO THE ALLIES FROM HIS POSITION IN ABWEHR, THE MILITARY INTELLIGENCE ARM OF NAZI GERMANY. AND THAT’S JUST TO GET US STARTED. ! WE COULD LOOK AT ANY ONE OF SEVERAL ASPECTS OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER AND SPEND THE ENTIRE HOUR AND MORE ON THAT FACET. A RECENT BIOGRAPHY OF BONHOEFFER IS ENTITLED “PASTOR, MARTYR, PROPHET, SPY.” WE’LL INSTEAD CONCENTRATE ON HIS SPIRITUAL THEOLOGY; HE DISLIKED THE WORD, “RELIGIOUS,” SO WE’LL GIVE HIM DUE DEFERENCE AND USE “RELIGIOUS” IF AT !1 ALL, SPARINGLY, THIS MORNING. BEFORE CHARGING HEADLONG INTO THIS THEOLOGY, OR MORE ESPECIALLY, THE PHASES OF HIS THEOLOGY, WHICH WERE MEANINGFULLY ADJUSTED OVER TIME BY LIFE’S EXPERIENCES, I HAVE AN ADDITIONAL COMMENT OR TWO. WHILE BONHOEFFER STANDS FOR MANY AS THE SYMBOL OF THE MODERN OR POST-MODERN CHRISTIAN, I DON’T BELIEVE HE WAS EITHER. IF NOT, THEN WHAT? HE DID NOT WARM TO THE RELATIVE; HE ALIGNED WITH THE ABSOLUTE. I WOULD ACTUALLY CALL HIM A THROWBACK TO ONE OF THE “ANCIENTS.” INDEED, BONHOEFFER IS OFTEN DUBBED GERMANY’S JEREMIAH, WHICH PROBABLY COMES CLOSE – AN OLD-TIME PROPHET; I THINK HE WOULD HAVE ACTUALLY FAVORED THAT HANDLE. -

PDF Download the Cost of Discipleship

THE COST OF DISCIPLESHIP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dietrich Bonhoeffer | 316 pages | 25 Sep 1995 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780684815008 | English | New York, United States The Cost of Discipleship PDF Book Digital Wish. The aim of this study was to describe and compare the time and monetary costs associated with recruiting and interviewing a diverse sample of older adults living in south Florida. Is it Time to Switch Banks? First Book, a non-profit based in Washington, D. This implies that military cultures stand in stark contrast to civilian entities within the western world. Among those is a comprehensive toolkit on starting a school supply drive. Full Access. There is a cost for everything. Williams, D. You can unsubscribe at any time. Print Book. Since the early days of mankind, human beings have sought to be part of a group, to be accepted and protected. Gilbert New York: Routledge, , pp. Privacy Statement. Bonhoeffer interpreted the demands as high, hence the term costly grace; the Christian must open up to Christ through genuine discipleship. Social Media Overview. Click here to uncover the best-in-class picks that landed a spot on our shortlist of the best savings accounts for Specialty Products. Instead of saying I prefer this to this, they would say: This have I loved and this have I hated. This raises a number of questions which are seldom addressed and expound upon from a theological and cultural point of view: Does Bonhoeffer describe a sort of elite Christianity with impracticable ideals which is thereby less relevant for contemporary Christians? If you do not really realize that this is an all-encompassing way to go at life now, you cannot compartmentalize. -

Bonhoeffer on Baptism: Discipline for the Sake of the Gospel GLENN L

Word & World 1/1 (1981) Copyright © 1981 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 20 Bonhoeffer on Baptism: Discipline for the Sake of the Gospel GLENN L. BORRESON First Lutheran Church, Decorah, Iowa The baptism of infants continues to be the means by which the overwhelming majority of persons is added to membership in the Lutheran Church.1 It is a simple yet important observation, therefore, that this sacrament provides a primary and often ready-made evangelism opportunity for the church. Parents, for example, normally expect the church to address the situation of their unbaptized infant. Out of an awareness of this opportunity, but more fundamentally out of faithfulness to her Lord, this same church is called to care theologically and pastorally about baptism. The contention of this article is that indiscriminate baptism of infants is often not only poor evangelism but also weakened proclamation. This common practice frequently ignores the context of the sacrament’s reception and overlooks the radical claims of the Gospel itself. For this reason, a special care is herein advocated—referred to as a baptismal discipline—which deals with these concerns and the sensitive questions of when and for whom the sacrament is administered. For the sake of the Gospel, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was advocating such a discipline among Lutherans more than a generation ago, and this is an attempt to learn from him.2 THE BAPTISMAL DILEMMA Historically, Martin Luther’s own defense of the baptism of infants was evoked by the Gospel itself. If infants were not permitted baptism because they lacked faith, the sacrament was threatened with becoming a humanly-constituted act 1In 1978, for example, 44,095 children under 16 years were received into The American Lutheran Church by baptism. -

The Orthodox Betrayal: How German Christians Embraced and Taught Nazism and Sparked a Christian Battle. William D

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 The Orthodox Betrayal: How German Christians Embraced and Taught Nazism and Sparked a Christian Battle. William D. Wilson Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, William D., "The Orthodox Betrayal: How German Christians Embraced and Taught Nazism and Sparked a Christian Battle." (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 160. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/160 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Orthodox Betrayal: How German Christians Embraced and Taught Nazism and Sparked a Christian Battle. An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History. By: William D. Wilson Under the mentorship of Brian K. Feltman Abstract During the years of the Nazi regime in Germany, the government introduced a doctrine known as Gleichschaltung (coordination). Gleichschaltung attempted to force the German people to conform to Nazi ideology. As a result of Gleichschaltung the Deutsche Christens (German Christians) diminished the importance of the Old Testament, rejected the biblical Jesus, and propagated proper Nazi gender roles. This thesis will argue that Deutsche Christen movement became the driving force of Nazi ideology within the Protestant Church and quickly dissented from orthodox Christian theology becoming heretical. -

A Hope for the Church of Christ: the Influence of Dietrich Bonhoeffer's Seminary at Findenwalde on the Church in Nazi Germany, 1935-1940

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Projects & Theses Theology 5-2014 A Hope for the Church of Christ: The Influence of Dietrich Bonhoeffer's Seminary at Findenwalde on the Church in Nazi Germany, 1935-1940 Gerri Beal Whitworth University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theology_etd Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beal, Gerri , "A Hope for the Church of Christ: The Influence of Dietrich Bonhoeffer's Seminary at Findenwalde on the Church in Nazi Germany, 1935-1940" Whitworth University (2014). Theology Projects & Theses. Paper 1. https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theology_etd/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Projects & Theses by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. A HOPE FOR THE CHURCH OF CHRIST: THE INFLUENCE OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER’S SEMINARY AT FINKENWALDE ON THE CHURCH IN NAZI GERMANY, 1935-1940 A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology at Whitworth University Gerri Beal B. A., Whitworth University May 2014 i Acknowledgements My first thanks are for the outstanding faculty of the Master of Arts in Theology program at Whitworth University. I am so grateful to Gerald Sittser for designing and directing this great program and to all the faculty members under whom I was privileged to study. Many thanks to Jeremy Wynne for help on administrative issues as well as preparation of the thesis presentation, and to Adam Neder for reading the thesis and asking questions at the presentation that I could actually answer and that illuminated Bonhoeffer’s work for the listeners. -

Christian Moral Action Year Group: 12

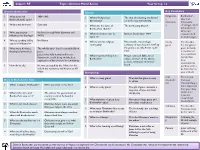

Subject: RE Topic: Christian Moral Action Year Group: 12 Key Vocabulary Dietrich Bonhoeffer Church Religionles Bonhoeffer’s 1 What years did 1906-1945 1 What is Religionless The idea of removing traditional s idea that Bonhoeffers life span? Christianity? set in the way Christianity Christianit Christianity 2 Where was he from? Germany 2 What was the name of The Confessing Church y should get rid of Bonhoeffers church? old-fashioned ideas and 3 What experience He lived through Nazi Germany and 3 What declaration was he Barmen Declaration 1934 separate itself influences his theology? WW2 apart of? from ideologies 4 Whose teaching did he Karl Barth 4 Where was his religious Finkenwalde- ran an illegal Costly The idea that use as an influence?= community? seminary. It was closed in 1937 by grace the free gift of 5 What were his three The wholly other God is revealed fully in the gestapo as only Arians could grace demands theological principles? Jesus train a response of Jesus is also fully human and for us true, sacrificial 5 What is spiritual disciple to Prayer-centered, Bible-based, Humans are social being and the best discipleship- Bonhoeffer? simple, focused on the whole- expression of this is found in community total person, communal and action abandonment based 6 How did he die? He was executed by the Nazi’s for his to Christ and to role in the resistance and his plot to kill be Christ like in Hitler Discipleship your attitude 1 What is cheap grace? The idea that grace is easy Civil The concept Duty to God and the state to obtain disobedie that your nce Christian Duty is 1 What is duty to Bonhoeffer? What you must do for God 2 What is costly grace? The gift of grace demands a more important response of true sacrificial than your duty 2 What is the state and The state is the government or discipleship to the state. -

Of 5 One of the Famous Quotes from the Lutheran Pastor and Holocaust

One of the famous quotes from the Lutheran Pastor and Holocaust victim Dietrich Bonhoeffer was: “Silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act. ” Dietrich Bonhoeffer. He might have been thinking about this when another German pastor, Hermann Gruner once said: “The time is fulfilled for the German people of Hitler. It is because of Hitler that Christ, God the helper and redeemer, has become effective among us. … Hitler is the way of the Spirit and the will of God for the German people to enter the Church of Christ.” Another pastor put it more succinctly: "Christ has come to us through Adolph Hitler.” So despondent had been the German people after the defeat of World War I and the subsequent economic depression that the charismatic Hitler appeared to be the nation's answer to prayer—at least to most Germans. One exception was theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was determined not only to refute this idea but also to topple Hitler. Bonhoeffer was not raised in a particularly radical environment. He was born into an aristocratic family. His mother was daughter of the preacher at the court of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his father was a prominent neurologist and professor of psychiatry at the University of Berlin. All eight children were raised in a liberal, nominally religious environment and were encouraged to dabble in great literature and the fine arts. Bonhoeffer's skill at the piano, in fact, led some in his family to believe he was headed for a career in music. -

The Cost of Discipleship a Sermon for September 4, 2016 Luke 14:2533 Lansdowne UMC

The Cost of Discipleship A sermon for September 4, 2016 Luke 14:2533 Lansdowne UMC Tomorrow is Labor Day. A lot of people are taking a 3day weekend before the full Fall schedule erupts on the scene. Yes, indeed, the slower paced days of summer are coming to a close. So, as your new pastor, it seems fitting that there be a nice, gentle word for us this morning. Something to encourage and strengthen all of us as the activities of school and church are about to get into full swing. I’ve gotta confess though I was so preoccupied with thinking about all of the activities that are starting up at church that I… uh… I didn’t get a chance to do much sermon preparation. And then just now gosh, this is embarrassing I forgot to pay attention to the Gospel reading. It’s ok though, because Jesus is always so comforting, isn’t he? Maybe if you don’t mind, I’ll just, uh, open up to it here and catch myself up on the encouraging message that it has for us today. What book was that? What chapter was it again? 14? Ok. Verse, uh, 25? I gotta be honest. I’m not really too familiar with this one, so I’ll just preach as I go along. Ok, here we go. “Large crowds were traveling with Jesus!” Ok, my brothers and sisters. You know Jesus started out with just a few followers. But now he’s apparently got a lot. It looks like Jesus was 1 finally becoming a truly successful preacher because successful preachers have large followings, right? We want crowds to come to our church, don’t we? I bet this is the part where Jesus tells us the key is to rapid church growth. -

The Cost of Discipleship

The Cost of Discipleship A Study of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Classic Book prepared by Peter Horne for Lawson Rd Church of Christ in Rochester, NY. Jan – Mar 2013 9 lessons My primary goal in studying this material is to expose my church to the concept of “cheap” and “costly” grace. Reflecting on this, I certainly didn’t gain 100% understanding or acceptance. However I do think though that most people in the class grasp the basics. I stopped the lessons at this point as the book really just turns into a study of the Sermon on the Mount and I’m not convinced that I want to use “Cost of Discipleship” as my primary text for that study. I included his discussion of Matt 5:1-16 as an opportunity to demonstrate how his teaching on discipleship and grace is applied to specific Scriptures. Other teachers may want to be more selective in the sections of the Sermon on the Mount they use to demonstrate this application. Primary Resources: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Cost of Discipleship (Touchstone: 1995). Jon Walker, Costly Grace (Leafwood Publishers: 2010). As an alternative to using my lesson plan, I would seriously consider just using Walker’s book. I found it much easier to read and apply to contemporary circumstances. I think enough of Bonhoeffer’s teaching is retained that it’s a good indirect way to expose people to his teaching. And makes reading Cost of Discipleship itself, unnecessary. What is Discipleship? Lawson Rd Church of Christ, Rochester, NY. 9 January, 2013 When I say the word “disciple” I’m guessing most of us think of The Twelve. -

The Cost of Discipleship

The Cost of Discipleship Louis Rushmore © 1985, revised 2018 Louis Rushmore www.gospelgazette.com www.WorldEvangelismMedia.com [email protected] Proofreaders: Rebecca Rushmore Martha Rushmore World Evangelism Media & Missions 705 Devine Street Winona, Mississippi 38967 Table of Contents PREFACE.................................................................................................4 CHAPTER1:DEFINITIONOFDISCIPLESHIP...............................................5 CHAPTER2:FORMULAOFDISCIPLESHIP...............................................10 CHAPTER3:TEACHINGSOFJESUSCHRIST#1........................................16 CHAPTER4:TEACHINGSOFJESUSCHRIST#2........................................26 CHAPTER5:ACTSANDTHEEPISTLES#1................................................30 CHAPTER6:ACTSANDTHEEPISTLES#2................................................37 CHAPTER7:THEEARLYCHURCH..........................................................43 CHAPTER8:LESSONSFROMTHEOLDTESTAMENT..............................50 CHAPTER9:BLESSINGSOFDISCIPLESHIP..............................................58 CHAPTER10:SPIRITUALIMMATURITY..................................................65 CHAPTER11:CONSEQUENCESOFREJECTINGDISCIPLESHIP..................72 CHAPTER12:MILITANTDISCIPLESHIP...................................................81 CHAPTER13:THEVALUEOFASOUL.....................................................86 WORKSCITED.......................................................................................93 GOD’SREDEMPTIVEPLAN.....................................................................94