Abstract Pluvial Deposits in Mudawwara, Jordan And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity. Wind Regimes, Spatial and Temporal Variations of the Aeolian Sediment Transport in Sistan Plain (East Iran) Dissertation Thesis Submitted for obtaining the degree of Doctor of Natural Science (Dr. rer. nat.) i to the Fachbereich Geographie Philipps-Universität Marburg by M.Sc. Hamidreza Abbasi Marburg, December 2019 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Christian Opp Physical Geography Faculty of Geography Phillipps-Universität Marburg ii To my wife and my son (Hamoun) iii A picture of the rock painting in the Golpayegan Mountains, my city in Isfahan province of Iran, it is written in the Sassanid Pahlavi line about 2000 years ago: “Preserve three things; water, fire, and soil” Translated by: Prof. Dr. Rasoul Bashash, Photo: Mohammad Naserifard, winter 2004. Declaration by the Author I declared that this thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis. Hamidreza Abbasi iv List of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. General Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Introduction and justification ........................................................................................................ -

100,000 Years of African Monsoon Variability Recorded in Sediments of the Nile Margin

Quaternary Science Reviews 29 (2010) 1342–1362 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev 100,000 Years of African monsoon variability recorded in sediments of the Nile margin Marie Revel a,*, E. Ducassou b, F.E. Grousset b, S.M. Bernasconi c, S. Migeon a, S. Revillon d, J. Mascle a, A. Murat e, S. Zaragosi b, D. Bosch f a Geosciences Azur, Observatoire Oce´anologique, La Darse, B.P. 48 06235 Villefranche/Mer, France b Universite´ Bordeaux 1, CNRS, UMR 5805-EPOC, avenue des faculte´s, 33405 Talence cedex, France c ETH Zurich, Geologisches Institut, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland d IFREMER, De´partement Ge´osciences Marines, BP70, 29280, Plouzane´, France e Cnam-Intechmer, BP324, 50103 Cherbourg, France f Laboratoire de Tectonophysique, Universite´ de Montpellier II, 34095 Montpellier, France article info abstract Article history: Multiproxy analyses were performed on core MS27PT recovered in hemipelagic sediments deposited on Received 20 April 2009 the Nile margin in order to reconstruct Nile River palaeohydrological fluctuations during the last 100,000 Received in revised form years. The strontium and neodymium isotope composition of the terrigenous fraction and the major 17 December 2009 element distribution reveal large and abrupt changes in source, oscillating between a dominant aeolian Accepted 4 February 2010 Saharan contribution during arid periods and a dominant Nile River contribution during pluvial periods. Iron content shows a strong correlation with strontium and neodymium isotopes. This allows the use of a high-resolution continuous Fe record as a proxy of Blue Nile sediment input over the last 100,000 years. -

L'.3350 Deposmon and DISSOLUTION of the MIDDLE DEVONIAN PRAIRIE FORMATION, Williston BASIN, NORTH DAKOTA and MONTANA By

l'.3350 DEPOsmON AND DISSOLUTION OF THE MIDDLE DEVONIAN PRAIRIE FORMATION, WilLISTON BASIN, NORTH DAKOTA AND MONTANA by: Chris A. Oglesby T-3350 A thesis submined to the Faculty and the Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date f:" /2 7 /C''i::-- i ; Signed: Approved: Lee C. Gerhard Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado - 7 Date' .' Samuel S. Adams, Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering II T-3350 ABSTRACf Within the Williston basin, thickness variations of the Prairie Formation are common and are interpreted to originate by two processes, differential accumulation of salt during deposition, and differential removal of salt by dissolution. Unambiguous evidence for each process is rare because the Prairie/Winnipegosis interval is seldom cored within the U.S. portion of the basin. Therefore indirect methods, utilizing well logs, provide the principal method for identifying characteristics of the two processes. The results of this study indicate that the two processes can be distinguished using correlations within the Prairie Formation. Several regionally correlative upward-brining, and probably shoaling-upward sequences occur within the Prairie Formation .. Near the basin center, the lowermost sequence is transitional with the underlying Winnipegosis Formation. This transition is characterized by thinly laminated carbonates that become increasingly interbedded with anhydrites of the basin-centered Ratner Member, the remainder of the sequence progresses up through halite and culminates in the halite-dominated Esterhazy potash beds. Two overlying sequences also brine upwards, however, these sequences lack the basal anhydrite and instead begin with halite and culminate in the Belle Plaine and Mountrail potash Members, respectively. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

The Arabian Gulf

Chapter 1 The Arabian Gulf Grace O. Vaughan, Noura Al-Mansoori, John A. Burt New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 1.1 THE REGION Bound by deserts and located between the north-eastern Arabian Peninsula and Iran, the Arabian Gulf (also known as the Persian Gulf, and hereafter known as “the Gulf”) is bordered by eight rapidly developing nations. The Gulf is located in the subtropics between 24°N and 30°N latitude and 48°E and 57°E longitude (Fig. 1.1), and is considered as a biogeographic subprovince of the northwestern Indian Ocean (Spalding et al., 2007). During summers, the Gulf is the hottest sea on the planet, particularly in the shallow southern basin where sea surface temperatures (SSTs) regu- larly exceed 35°C in August. Sea temperatures are also highly variable among seasons, ranging over 20°C between summer and winter. Geologically, the Gulf is relatively young with coastlines that formed only in the past 3000–6000 years when polar ice sheets receded (Riegl & Purkis, 2012a). Today, the Gulf is bordered to the northeast by the Zagros mountains in Iran and the Hajar mountains in the Musandam peninsula and in the southwest by the sedimentary Arabian coast (Purser & Seibold, 1973). Presently, it covers an area of 250,000 km2 (Riegl & Purkis, 2012a). Generally, terrestrial systems sur- rounding the Gulf are arid to hyperarid (Riegl & Purkis, 2012a), limiting the input of freshwater to this semienclosed sea. The main freshwater input enters at the northern Gulf at the Shatt Al Arab waterway through the Tigris, Euphrates, and the Karun rivers (Sheppard, Price, & Roberts, 1992), although recent damming efforts have resulted in substantial reductions in freshwater discharge from these rivers (Sheppard et al., 2010). -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

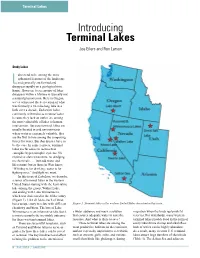

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Nutrient Dynamics in the Jordan River and Great

NUTRIENT DYNAMICS IN THE JORDAN RIVER AND GREAT SALT LAKE WETLANDS by Shaikha Binte Abedin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Shaikha Binte Abedin 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Shaikha Binte Abedin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Ramesh K. Goel , Chair 03/08/2016 Date Approved Michael E. Barber , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved Steven J. Burian , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved and by Michael E. Barber , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In an era of growing urbanization, anthropological changes like hydraulic modification and industrial pollutant discharge have caused a variety of ailments to urban rivers, which include organic matter and nutrient enrichment, loss of biodiversity, and chronically low dissolved oxygen concentrations. Utah’s Jordan River is no exception, with nitrogen contamination, persistently low oxygen concentration and high organic matter being among the major current issues. The purpose of this research was to look into the nitrogen and oxygen dynamics at selected sites along the Jordan River and wetlands associated with Great Salt Lake (GSL). To demonstrate these dynamics, sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and nutrient flux experiments were conducted twice through the summer, 2015. The SOD ranged from 2.4 to 2.9 g-DO m-2 day-1 in Jordan River sediments, whereas at wetland sites, the SOD was as high as 11.8 g-DO m-2 day-1. -

Middle-To-Late-Pleistocene.Pdf

Quaternary International 382 (2015) 200e214 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Middle to Late Pleistocene human habitation in the western Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia * Eleanor M.L. Scerri a, , Paul S. Breeze b, Ash Parton c, Huw S. Groucutt c, Tom S. White c, Christopher Stimpson c, Laine Clark-Balzan c, Richard Jennings c, Abdullah Alsharekh d, Michael D. Petraglia c a PACEA, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5199 Batiment^ B8, Allee Geoffrey St Hilaire, CS 50023, 33615 Pessac Cedex, France b Department of Geography, King's College London, K4U.06 Strand Campus, London WC2R 2LS, United Kingdom c School of Archaeology, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, 28 New Barnett House, Little Clarendon Street, Oxford OX1 2HU, United Kingdom d Department of Archaeology, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2627, Riyadh 12372, Saudi Arabia article info abstract Article history: The Nefud Desert is crucial for resolving debates concerning hominin demography and behaviour in Available online 8 October 2014 the Saharo-Arabian belt. Situated at the interface between the Mediterranean Westerlies and African Monsoonal climate systems, the Nefud lies at the centre of the arid zone crossed by Homo sapiens Keywords: dispersing into Eurasia and the edges of the southernmost known extent of the Neanderthal range. In Pleistocene Palaeoenvironments 2013, the Palaeodeserts Project conducted an intensive survey of the western Nefud, to: (1) evaluate Lower Palaeolithic Pleistocene population dynamics in this important region of the Saharo-Arabian belt and (2) Middle Palaeolithic contribute towards understanding early modern human range expansions and interactions between different hominin species. -

The Environmental History and Present Condition of Saudi Arabia's

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The environmental history and present condition of Saudi Arabia's northern sand seas by J. W. Whitney I/, D. J. Faulkender, and Meyer Rubin 2/ Open-File Report 83- 7V Prepared for Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources Jiddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature I/ U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, CO 80225 2/ U.S. Geological Survey, Radiocarbon Lab., Reston, VA 22092 1983 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION............................................ 2 PHYSICAL SETTING AND SEDIMENT SOURCES OF THE SAND SEAS.. 4 AGE AND ORIGIN OF THE SAND SEAS......................... 8 QUATERNARY EOLIAN AND LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS............... 12 Dune systems........................................ 12 Active versus stable dunes.......................... 15 Pleistocene and Holocene lake deposits.............. 18 Diatomite........................................... 24 PRESENT CONDITION OF THE SAND SEAS...................... 25 Precipitation and temperature....................... 25 Vegetation.......................................... 27 Modern and paleo-wind systems....................... 29 ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE SAND SEAS.................. 32 DATA STORAGE............................................ 35 REFERENCES CITED........................................ 36 ILLUSTRATIONS -

Origin of Intraformational Folds in the Jurassic Todilto Limestone, Ambrosia Lake Uranium Mining District, Mckinley and Valencia Counties, New Mexico by Morris W

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Origin of Intraformational Folds in the Jurassic Todilto Limestone, Ambrosia Lake Uranium Mining District, McKinley and Valencia Counties, New Mexico By Morris W. Green U.S. Geological Survey Open-file Report 82-69 1982 Contents Page Abstract................................................................ 1 Introducti on............................................................ 3 Stratigraphy and Environments of Deposition.............................3 The Formation of Intraformational Folds................................10 Todilto Uranium Deposits...............................................22 Exploration and Favorability...........................................24 References ci ted....................................................... 25 Illustrations Figure 1. Index map showing location of mineral belt, the Todilto study area, and adjacent areas.....................4 2. Index map of the Ambrosia Lake mining area...................5 3. Schematic diagram showing a segment of the Todilto depositional basin.........................................9 4. Remnants of a Summerville (Js) eolian dune overlying the Todilto Limestone (Jt)................................12 5. Schematic diagram showing the plastic and shear phases of Todilto load deformation...............................13 6. Large-scale, low amplitude intraformational fold within the Todilto Limestone.....................................14 7. Large-scale, high amplitude, intraformational fold within the Todilto Limestone..............................14 -

Coral Reefs Within a Siliciclastic Setting, 1997

Proc 8th Int Coral Reef Sym 2:1737-1742.1997 CORAL REEFS AND CARBONATE PLATFORMS WITHIN A SILICICLASTIC SETTING. GENERAL ASPECTS AND EXAMPLES FROM THE LATE JURASSIC OF PORTUGAL. Reinhold Leinfelder Institute of Geology and Paleontology, University of Stuttgart, Herdweg 51, D-70174 Stuttgart, Germany. ABSTRACT in the water (op. cit.). Additionally, terrigeneous influx is mostly accompanied by an unfavourable increase Both in the Modern and Ancient examples coral reefs and in nutrient and sometimes even freshwater influx. carbonate platforms occur frequently very close to or even directly within areas of siliciclastic sediment- ation. Particularly fine grained, often suspended terri- geneous influx is mostly problematic for the reef fauna due to lowering of illumination and oxygenation, in- TableÊ1: Possible negative effects of terrigeneous creasing nutrient values or directly settling on the influx on reefs: organims. The modern examples show that reef growth in such settings is only possible by the existence of sheltering mechanisms such as arid climate, structural REEFS AND SILICS? WHAT'S BAD ABOUT IT? and sedimentary traps or longshore currents. If not completely effective, reefs may still prosper under 1 . Increase of nutrient concentration reduced but noticeable siliciclastic sedimentation, but 2 . Freshwater influx both composition and diversity of the reefs changes drastically. The Ancient examples show that temporal 3 . Reduction of oxygen concentration relations are important as well: Autocyclic switches in 4 . Impoverished illumination depositional systems and especially allocyclic events 5 . Loss of hard substrates such as tectonic activation/deactivation or sea level 6 . Pollution / suffocation of reef organisms change may open and close reef windows through time.