Part 4: Advanced Life Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Life Support + First Aid for Healthcare Providers 2020 Course Introduction

Basic Life Support + First Aid for Healthcare Providers 2020 Course Introduction SECTION 1: Foundational concepts of BCLS SECTION 2: Response to an adult in cardiac arrest SECTION 3: Basic Life Support for infants and children SECTION 4: Automated external defibrillation in infants and children SECTION 5: Preventing cardiac arrest SECTION 6: First aid for adults SECTION 7: First aid for children Activity Summary • Activity Title: Basic Life Support (BLS) & First Aid (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), Automated External Defibrillator (AED), and First Aid) • Release date: 2021-06-01 • Expiration date: 2024-06-01 • Estimated time to complete activity: 8 hours • This course is accessible with any web browser. We recommend recent versions of • Google Chrome, Internet Explorer 9 and later, or Apple iPad. • This course is jointly provided by Pacific Medical Training and Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM). You may reach PIM at [email protected]. Target Audience This activity has been designed to meet the educational needs of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, pharmacists and dentists involved in the care of patients who require advanced life support. 3103 Philmont Ave, Suite 308 • Huntingdon Valley, PA 19006 • 800-417-1748 page 1 Educational Objectives After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to: • Explain the change in emphasis from airway and ventilation to compressions and perfusion. • Select the correct order of interventions for the victim of cardiopulmonary arrest. • List the steps required to safely operate an AED. • Differentiate between adult and pediatric guidelines for CPR. • Explain how to apply the various first aid interventions. • Describe how to apply the various pediatric first aid interventions. -

Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality 1

Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality 1 Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality Web-based Integrated 2010 & 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Key Words: cardiac arrest cardiopulmonary resuscitation defibrillation emergency 1 Highlights & Introduction 1.1 Highlights: Lay Rescuer CPR Summary of Key Issues and Major Changes Key issues and major changes in the 2015 Guidelines Update recommendations for adult CPR by lay rescuers include the following: The crucial links in the out-of-hospital adult Chain of Survival are unchanged from 2010, with continued emphasis on the simplified universal Adult Basic Life Support (BLS) Algorithm. The Adult BLS Algorithm has been modified to reflect the fact that rescuers can activate an emergency response (ie, through use of a mobile telephone) without leaving the victim’s side. It is recommended that communities with people at risk for cardiac arrest implement PAD programs. Recommendations have been strengthened to encourage immediate recognition of unresponsiveness, activation of the emergency response system, and initiation of CPR if the lay rescuer finds an unresponsive victim is not breathing or not breathing normally (eg, gasping). Emphasis has been increased about the rapid identification of potential cardiac arrest by dispatchers, with immediate provision of CPR instructions to the caller (ie, dispatch-guided CPR). The recommended sequence for a single rescuer has been confirmed: the single rescuer is to initiate chest compressions before giving rescue breaths (C-A-B rather than A-B-C) to reduce delay to first compression. The single rescuer should begin CPR with 30 chest compressions followed by 2 breaths. -

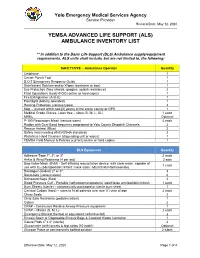

(Als) Ambulance Inventory List

Yolo Emergency Medical Services Agency Service Provider Revised Date: May 12, 2020 YEMSA ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT (ALS) AMBULANCE INVENTORY LIST ** In addition to the Basic Life Support (BLS) Ambulance supply/equipment requirements, ALS units shall include, but are not limited to, the following: SAFETY/PPE – Ambulance Operator Quantity Cellphone 1 Center Punch Tool 1 D.O.T Emergency Response Guide 1 Disinfectant Solution and/or Wipes (container or box) 1 Eye Protection (face shields, goggles, splash resistance) 2 Field Operations Guide (FOG) online or hard copies 1 Fire Extinguisher (A-B-C) 1 Flashlight (battery operated) 1 Hearing Protection (various types) 2 Map – (current within two [2] years) of the entire county or GPS 1 Medical Grade Gloves, Latex free – sizes (S, M, L, XL) 1 each MREs Optional P-100 Respiratory Mask (various sizes) 4 each Radios with Dual Band frequency programed to Yolo County Dispatch Channels 2 Rescue Helmet (Blue) 2 Safety Vest meeting ANSI/OSHA standards 2 Waterless Hand Cleanser (dispensing unit or wipes) 1 YEMSA Field Manual & Policies (current) online or hard copies 1 BLS Equipment Quantity Adhesive Tape 1", 2", or 3" 2 each Ankle & Wrist Restraints (4 per set) 2 sets Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM) - Self-inflating resuscitation device, with clear mask, capable of 1 each use with O2 (adult/pediatric/infant; mask sizes: adult/child/infant/neonate) Bandages (Rolled) 2" or 3" 3 Band-Aids (various sizes) 6 Biohazard Bags (Red) 2 Blood Pressure Cuff - Portable (sphygmomanometers) (adult/large arm/pediatric/infant) 1 each -

The Laryngeal Mask Airway: Potential Applications in Neonates

F485 Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed: first published as 10.1136/adc.2003.038430 on 21 October 2004. Downloaded from PERSONAL PRACTICE The laryngeal mask airway: potential applications in neonates D Trevisanuto, M Micaglio, P Ferrarese, V Zanardo ............................................................................................................................... Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004;89:F485–F489. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.038430 The laryngeal mask airway is a safe and reliable airway 2.5–5 kg.11 It has been postulated that a smaller size (0.5) could be useful in preterm management device. This review describes the insertion newborns. However, there are reports of techniques, advantages, limitations, and potential successful use of size 1 in preterm neonates applications of the laryngeal mask airway in neonates. weighing 0.8–1.5 kg.12–15 ........................................................................... (2) Fully deflate the cuff as described in the manual, and lubricate the back of the mask tip (for neonates in the labour ward, he ability to maintain a patent airway and lubrication may not be necessary, as oral provide effective positive pressure ventilation and pharyngeal secretions may reproduce T(PPV) is the main objective of neonatal this function). resuscitation and all anaesthesiological proce- (3) Press (flatten) the tip of the LMA against the dures.1–6 This is currently achieved with the use hard palate. During this manoeuvre, the of a face mask or an endotracheal tube. Both of these devices have major limitations from a operator should grasp the LMA like a pen strictly anatomical point of view and require with the index finger at the junction adequate operator skills. In certain situations, between the mask and the distal end of the both face mask ventilation and tracheal intuba- airway tube. -

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations Printed: August 2016 Effective: September 11, 2016 1 9/16/2016 Statutes and Regulations Table of Contents Title 63 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 3 - 13 Sections 1-2501 to 1-2515 Constitution of Oklahoma Pages 14 - 16 Article 10, Section 9 C Title 19 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 17 - 24 Sections 371 and 372 Sections 1- 1201 to 1-1221 Section 1-1710.1 Oklahoma Administrative Code Pages 25 - 125 Chapter 641- Emergency Medical Services Subchapter 1- General EMS programs Subchapter 3- Ground ambulance service Subchapter 5- Personnel licenses and certification Subchapter 7- Training programs Subchapter 9- Trauma referral centers Subchapter 11- Specialty care ambulance service Subchapter 13- Air ambulance service Subchapter 15- Emergency medical response agency Subchapter 17- Stretcher aid van services Appendix 1 Summary of rule changes Approved changes to the June 11, 2009 effective date to the September 11, 2016 effective date 2 9/16/2016 §63-1-2501. Short title. Sections 1-2502 through 1-2521 of this title shall be known and may be cited as the "Oklahoma Emergency Response Systems Development Act". Added by Laws 1990, c. 320, § 5, emerg. eff. May 30, 1990. Amended by Laws 1999, c. 156, § 1, eff. Nov. 1, 1999. NOTE: Editorially renumbered from § 1-2401 of this title to avoid a duplication in numbering. §63-1-2502. Legislative findings and declaration. The Legislature hereby finds and declares that: 1. There is a critical shortage of providers of emergency care for: a. the delivery of fast, efficient emergency medical care for the sick and injured at the scene of a medical emergency and during transport to a health care facility, and b. -

State Ambulance Policies and Services (OEI-09-95-00410; 2/98)

- - -- -------- --of -- - OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL FEBRUARY 1998 OEI-09-95-00410 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE To provide baseline data about the ambulance industry and determine how State and local ordinances affect the delivery of ambulance services. BACKGROUND According to Section 1861(s)(7) of Social Security Act, Medicare pays for medically necessary ambulance services when other forms of transportation would endanger the beneficiary’s health. Ambulance suppliers provide two distinct levels of service--advanced life support and basic life support. The major distinctions between the levels are the types of vehicles and the skills of the personnel and the services they render. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) is considering proposed Medicare regulations that would base reimbursement for ambulance services on the patient’s condition rather than the type of vehicle and personnel used. The final rule may include a special waiver for suppliers in non-Metropolitan Statistical Areas who would be hurt financially if they use only advanced life support ambulances. The HCFA may consider several options and may include a special waiver only if HCFA is convinced through overwhelming information of the need for the waiver. We decided to examine the effect and need for a special waiver based on Metropolitan Statistical Areas and non-Metropolitan Statistical Areas. In addition, we developed baseline information on the number of ambulance suppliers, vehicles, and personnel nationwide. We conducted in-person and telephone interviews with 53 State Emergency Medical Services Directors for the 50 States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Using a structured discussion guide, we (1) identified State, county, and municipal mandates that require specific levels of ambulance services and (2) obtained baseline data on the number of suppliers, licensed vehicles, and certified personnel operating within the States in 1995 and 1996. -

Intravenous Alfaxalone Anaesthesia in Two Squamate Species: Eublepharis Macularius and Morelia Spilota Cheynei

INTRAVENOUS ALFAXALONE ANAESTHESIA IN TWO SQUAMATE SPECIES: EUBLEPHARIS MACULARIUS AND MORELIA SPILOTA CHEYNEI Tesi per il XXIX Ciclo del Dottorato in Scienze Veterinarie, Curriculum Scienze Cliniche Veterinarie Dipartimento di Scienze Veterinarie, Universita’ degli Studi di Messina Tutor: Prof. Filippo Spadola Cotutor: Prof. Zdenek Knotek Dr. Manuel Morici Sommario L’anestesia negli Squamati è una costante sfida della medicina e chirurgia dei rettili. Le differenze morfo-fisiologiche di questi taxa, rendono difficilmente applicabile i comuni concetti di anestesiologia veterinaria usati con successo negli altri animali da compagnia. Diversi protocolli anestetici sono stati utilizzati, sia per l’induzione che per il mantenimento, sia negli ofidi che nei sauri, ma con risultati variabili. Di fatti la maggior parte dei protocolli risultano in induzione o recuperi troppo brevi o troppo lunghi. L’obbiettivo di questa tesi dottorale è di valutare l’efficacia di un anestetico steroideo (alfaxalone), somministrato per via endovenosa in due specie di squamati usati come modello: il geco leopardo (Eublepharis macularius) e il pitone tappeto (Morelia spilota cheynei). Due metodi di somministrazione endovenosa (vena giugulare nei gechi e vena caudale nei serpenti) sono stati analizzati e descritti, usando un dosaggio di anestetico di 5 mg/kg in 20 gechi leopardo, e di 10 mg/kg in 10 pitoni tappeto. Nei gechi il tempo di induzione, il tempo di perdita del tono mandibolare, l’intervallo di anestesia chirurgica e il recupero completo sono stati rispettivamente di 27.5 ± 30.7 secondi, 1.3 ± 1.4 minuti, 12.5 ± 2.2 minuti and 18.8 ± 12.1 minuti. Nei pitoni tappeto, il tempo di induzione, la perdita di sensazione, il tempo di inserimento del tubo endotracheale, l’intervallo di anestesia chirurgica e il recupero sono stati rispettivamente di 3.1±0.8 minuti, 5.6±0.7 minuti, 6.9±0.9 minuti, 18.8±4.7 minuti, e 36.7±11.4 minuti. -

Collective Advanced Life Support Ambulance an Innovative Transportation of Critical Care Patients by Bus in COVID-19 Pandemic Response

Collective Advanced Life Support Ambulance An Innovative Transportation of Critical Care Patients by Bus in COVID-19 Pandemic Response Thierry Lentz SAMU 92 Charles Groizard SAMU 92 Abel Colomes SAMU 92 Anna Ozguler ( [email protected] ) INSERM https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9277-610X Michel Baer SAMU 92 Thomas Loeb SAMU 92 Research article Keywords: Emergency medical service, Critical care transport, Interhospital transfer of critically ill patients, Collective Transport, Mass casualty incidents, Disaster DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-48425/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract Background: During the COVID-19 pandemic, as the number of available Intensive Care beds in France did not meet the needs, it appeared necessary to transfer a large number of patients from the most affected areas to the less ones. Mass transportation resources were deemed necessary. To achieve that goal, the concept of a Collective Advanced Life Support Ambulance (CALSA) was proposed in the form of a long-distance bus re-designed and equipped so as to accommodate up to six intensive care patients and allow Advanced Life Support (ALS) techniques to be performed while en route. Methods: The expected beneƒt of the CALSA, when compared to ALS ambulances accommodating a single patient, was to reduce the resources requirements, in particular by a lower personnel headcount for several patients being transferred to the same destination. A foreseen prospect, comparing to other collective transportation vectors such as airplanes, was the door-to-door capability, minimalizing patients’ handovers for safety concerns and time e∆ciency. -

Tracheal Intubation

//Tracheal Intubation http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/b/book.do?m... Tracheal Intubation Technique As previously discussed, because of differences in anatomy, there are differences in techniques for intubating the trachea of infants and children compared with adults.[1–4,17–19,99,114,115] Because of the smaller dimensions of the pediatric airway there is increased risk of obstruction with trauma to the airway structures. A technique to be avoided is that in which the blade is advanced into the esophagus and then laryngeal visualization is achieved during withdrawal of the blade. This maneuver may result in laryngeal trauma when the tip of the blade scrapes the arytenoids and aryepiglottic folds. There are several approaches to exposing the glottis in infants with a Miller blade. One philosophy consists of advancing the laryngoscope blade under constant vision along the surface of the tongue, placing the tip of the blade directly in the vallecula and then using this location to pivot or rotate the blade to the right to sweep the tongue to the left and adequately lift the tongue to expose the glottic opening. This avoids trauma to the arytenoid cartilages. One can thus lift the base of the tongue, which in turn lifts the epiglottis, exposing the glottic opening. If this technique is unsuccessful, one may then directly lift the epiglottis with the tip of the blade (see Video Clip 12-1, Coming Soon). Another approach is to insert the Miller blade into the mouth at the right commissure over the lateral bicuspids/incisors (paraglossal approach). The blade is advanced down the right gutter of the mouth aiming the blade tip toward the midline while sweeping the tongue to the left. -

Goals of Care and End of Life in the ICU

Goals of Care and End of Life in the ICU Ana Berlin, MD, MPH, FACS KEYWORDS Goals of care Shared decision making ICU Functional and cognitive outcomes End-of-life care Palliative care Communication KEY POINTS The trauma and long-term sequelae of critical illness affect not only patients but also their families and caregivers. Unrealistic expectations and erroneous assumptions about the outcomes acceptable to patients are important drivers of misguided and goal-discordant medical treatment. Compassionately delivering accurate and honest prognostic information inclusive of func- tional, cognitive, and psychosocial outcomes is crucial for helping patients and families understand what to expect from an episode of surgical crticial illness. Skilled communication and shared decision-making strategies ensure that treatments provided in the ICU are aligned with realistic and attainable patient goals. Attentive management of physical and nonphysical symptoms, including the psychosocial and spiritual needs of families and caregivers, eases suffering in the ICU and beyond. INTRODUCTION There is little doubt that the past half-century has seen tremendous advances in surgical critical care. The advent of lung-protective ventilation in the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the evolution of balanced resusci- tation strategies for the reduction of abdominal compartment syndrome, and the aggressive deployment of prevention and treatment strategies against the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis, along with many other technological innovations, have markedly reduced the morbidity and mortality associated with critical illness and multiorgan system failure. Nevertheless, at times even the Disclosure Statement: Support for Dr A. Berlin’s preparation of this article was provided by the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources and Services Administration through Grant D34HP26020. -

Required ALS and BLS Equipment and Supplies

S T A T E O F H A W A I I D E P A R T M E N T O F H E A L T H ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT and SUPPLIES FOR BASIC and ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT Ambulance Service Standards Revised 10-14-10 ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT FOR BASIC LIFE SUPPORT Ambulance cot w/ 3 seatbelts Sheets, linen or disp., 4 ea Cot fasteners, Floor/Wall Mount Blankets, non-synthetic, 4 ea Portable oxygen unit 360L min. tank Gauze pads, sterile, 3x3 min, 24 ea Flowmeter 0-15L/min Gauze rolls, sterile, 2" x 5 yds, 4 ea Positive pressure elder-type valve Gauze rolls, sterile 3"/4" x 5 yds, 4 ea Oxygen masks, clear, disposable, adult/pedi 1 ea Gauze rolls, sterile, 6" x 5 yds, 4 ea Oxygen nasal cannula, disposable 2 ea Triangle bandage, 40" min, 3 ea Oropharyngeal airways, adult/ped/infant 1 ea Universal dressing, 8 x 10 min, sterile, 1 ea Nasopharyngeal airways, 2 ea Tape, 1" and 2" x 5 yds, 1 ea Oxygen tanks, spare, 360L min, 2 ea Bandaids, assorted Bag-valve-mask, pedi w/02 reservoir Plastic wrap, 12" x' 12" min, 1 ea Bag-valve-mask, adult w/02 reservoir Burn sheets, sterile, 2 ea Suction, portable, battery operated Sphygmomanometer, adult, 1 ea Widebore tubing Extra large adult, 1 ea Rigid pharyngeal suction tip Pediatric, 1 ea Suction catheters 5, 10, 14, 18fr, 1 ea Stethescope, 1 ea Bite sticks (mouth gag), 2 ea Scissors, bandage, 5" min Ammonia inhalants, 3 ea Thermometer, oral and rectal, 1 ea Antiseptic swabs, 50 ea Spineboard, short, w/straps, 1 ea Bulb syringe, 3 oz. -

Removal of the Endotracheal Tube (2007)

AARC GUIDELINE: REMOVAL OF THE ENDOTRACHEAL TUBE AARC Clinical Practice Guideline Removal of the Endotracheal Tube—2007 Revision & Update RET 1.0 PROCEDURE RET 3.0 ENVIRONMENT Elective removal of the endotracheal tube from The endotracheal tube should be removed in an en- adult, pediatric, and neonatal patients. vironment in which the patient can be physiologi- cally monitored and in which emergency equipment RET 2.0 DESCRIPTION/DEFINITION and appropriately trained health care providers with The decision to discontinue mechanical ventilation airway management skills are immediately avail- involves weighing the risks of prolonged mechani- able (see RET 10.0 and 11.0). cal ventilation against the possibility of extubation failure.1,2 This guideline will focus on the predictors RET 4.0 INDICATIONS/OBJECTIVES that aid the decision to extubate, the procedure re- When the airway control afforded by the endotra- ferred to as extubation, and the immediate postextu- cheal tube is deemed to be no longer necessary for bation interventions that may avoid potential rein- the continued care of the patient, the tube should be tubation. This review will not address weaning removed. Subjective or objective determination of from mechanical ventilation, accidental extubation, improvement of the underlying condition impairing nor terminal extubation. pulmonary function and/or gas exchange capacity is made prior to extubation.2 To maximize the like- 2.1 The risks of prolonged translaryngeal intu- lihood for successful extubation, the patient should bation include but are not limited to: be capable of maintaining a patent airway and gen- 2.1.1 Sinusitis3,4 erating adequate spontaneous ventilation.