Squatting and the Undocumented Migrants Struggle in the Netherlands1 Deanna Dadusc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Albeniz Tugce Ezme Bachelor of City and Regional Planning Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey January 2009 Committee Chair: Dr. David Varady Submitted February 19, 2014 Abstract Sulukule was one of the most famous neighborhoods in Istanbul because of the Romani culture and historic identity. In 2006, the Fatih Municipality knocked on the residents’ doors with an urban renovation project. The community really did not know how they could retain their residence in the neighborhood; unfortunately everybody knew that they would not prosper in another place without their community connections. They were poor and had many issues impeding their livelihoods, but there should have been another solution that did not involve eviction. People, associations, different volunteer groups, universities in Istanbul, and also some trade associations were supporting the people of Sulukule. The Sulukule Platform was founded as this predicament began and fought against government eviction for years. In 2009, the area was totally destroyed, although the community did everything possible to save their neighborhood through the support of the Sulukule Platform. I cannot say that they lost everything in this process, but I also cannot say that anything was won. I can only say that the Fatih Municipality soiled its hands. No one will forget Sulukule, but everybody will remember the Fatih Municipality with this unsuccessful project. -

WAH Catalogue

Community Engaged Practice – An Emerging Issue for Australian ARIs 41 Contents Lisa Havilah Children, Creativity, Education& ARIs: Starting Young, Building Audiences 43 Claire Mooney The Feeling Will Pass... Space/Not Space 46 WAH Exhibition Documentation & Texts Brigid Noone The Feeling Will Pass… 2 The Subjectivity of Success 48 Brianna Munting Scot Cotterell We are (momentarily) illuminated 4 ARIs and Career Trajectories in the Arts 50 Georgie Meagher Lionel Bawden Exhibition Audience Survey Infographic Display 6 Money 52 Blood & Thunder Sarah Rodigari Tension Squared 10 ARIs in the National Cultural Policy 54 Cake Industries Tamara Winikoff The ooo in who? 12 Hossein Ghaemi WAH Debate It Was Never Meant To Last (BIG TIME LOVE) 16 The Half-Baked Notes of the First Speaker 57 Michaela Gleave Frances Barrett When there is no more anxiety, there is no more hope 20 Biljana Jancic WAH Essays I am here 22 We are...have been...here: Sebastian Moody a brief, selective look at the history of Sydney ARIs 62 Jacqueline Millner Unworkable Action 24 Nervous Systems A History of Sucess? 66 Din Heagney Path to the Possible: critique and social agency in artist run inititaives 27 Hugh Nichols Out of the Past: Beyond the Four Fundamental Fallacies of Artist Run Initiatives 70 Experiment 03: Viral Poster Experiment 30 Alex Gawronski S.E.R.I. (Carl Scrase) Dear friends, artists, and cultural workers 74 WAH Symposium: Presentations & Reflections Jonathan Middleton We Are Here – A View from the UK 79 We Are Here 34 Lois Keidan Welcome by Kathy Keele We Are Here 83 We were there. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project STEVE McDONALD Interviewed by: Dan Whitman Initial Interview Date: August 17, 2011 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Education MA, South African Policy Studies, University of London 1975 Joined Foreign Service 1975 Washington, DC 1975 Desk Officer for Portuguese African Colonies Pretoria, South Africa 1976-1979 Political Officer -- Black Affairs Retired from the Foreign Service 1980 Professor at Drury College in Missouri 1980-1982 Consultant, Ford Foundation’s Study 1980-1982 “South Africa: Time Running Out” Head of U.S. South Africa Leadership Exchange Program 1982-1987 Managed South Africa Policy Forum at the Aspen Institute 1987-1992 Worked for African American Institute 1992-2002 Consultant for the Wilson Center 2002-2008 Consulting Director at Wilson Center 2009-2013 INTERVIEW Q: Here we go. This is Dan Whitman interviewing Steve McDonald at the Wilson Center in downtown Washington. It is August 17. Steve McDonald, you are about to correct me the head of the Africa section… McDONALD: Well the head of the Africa program and the project on leadership and building state capacity at the Woodrow Wilson international center for scholars. 1 Q: That is easy for you to say. Thank you for getting that on the record, and it will be in the transcript. In the Wilson Center many would say the prime research center on the East Coast. McDONALD: I think it is true. It is a think tank a research and academic body that has approximately 150 fellows annually from all over the world looking at policy issues. -

Servicing the Story First: the Aesthetics and Politics of the Representation of Refugees

Servicing the Story First: The Aesthetics and Politics of the Representation of Refugees Alison Ranniger | Student Number 1943391 Master of Arts and Culture / Servicing the Story First: The Aesthetics and Politics of the Representation of Refugees Alison Ranniger MA Arts and Culture Specialization: Contemporary Art in a Global Perspective Leiden University Supervisor: Prof.dr. Kitty Zijlmans Leiden, The Netherlands January 2020 1 / Abstract: This thesis reflects on historical and contemporary issues around representational practices and visual politics of creating and displaying refugee subject matter in art. This paper aims to open up broader discussions about cultural institutions and artists’ responsibilities in producing counter-narratives that service refugees’ perspectives and voices. By doing so, museums and relevant artists can avoid perpetuating existing tropes and ensure that their own agendas are secondary to what the subject of their work (in this case, refugee and asylum seekers) wishes to convey. By means of concrete examples of artists and artwork, the author attempts to bring forth a discussion on the ethical considerations for artists involved in collaborative projects with refugees and asylum seekers by questioning and challenging various frameworks and existing modes of representation within contemporary art discourse. The author proposes different modes of representation that service the ‘protagonist’s’ story first, referring to concepts and practices through which to understand the construction of visual narratives -

Ffiffiffiffi*O*M% I.%Ff, Pesgf#Ffii"T$

&" gr I $ & r gcfuq.1 1GT.uG:' ss,jj o -Y bqrtd-Li"{; oE ffiffiffiffi*o*m% i.%ff, pesgf#ffii"T$ utr) tt, O L \B-) 8^t-b:a *t cE -.THE M&If$ ORCANJI BERS- Ss 1 a 3 c o) c o rgs -u g? it ".; \., PE i<s.' €'d S E.b <oP TQ- r-a6 ?iclore \ Su.a.to.o- d ,9 9; 96 L Ea d go-a gL 3e 'sg sll'g-'a) qf i O:\6 E turl*"f q XgE F f 3 fi refe lrrrP : /l wwu. fodl f,este'' ' "A ennoll f;anue,ro @ rnad.prk@g *k. corw €moTl Strzonra @ Sous!'es dJhot^olt - cor j; d Ladyfest, Ladyfest, Ladyfest, ... What is all this fuss about? You may ask? \{ell, if you stiil havenot heard about it, your grrl-head was under the crowds for the past 16 months at least (or are you one of thosc Hole fanatics that think rioting is putting on eye-liner?). LSDJrrr* ntH,Arrs Ii.ayfedts tttg current happening gathering for worldwide (feminisVactivi st/or just loudmouthed and opinionated) female artists. Born in 2000 with the great efforts of a team of ladies some of us know from bands and labels we cherish, this festival has had successions all over the Us and recently, in Europe. The first European one was in Glasgow, in August 2001. From these two fests, teams were born of more ladies that wanted to bring Ladyfest to their city. For, Ladyfests should be everywhere! For more info on what will happen in2002, go to: www.ladyfest.org and www'ladyfesteurope.org What happens at a Ladlfest? The basic concept of a Ladyfest is: to celebrate female talent in all its forms. -

Urban Europe.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag

omslag Urban Europe.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag. All Pages In Urban Europe, urban researchers and practitioners based in Amsterdam tell the story of the European city, sharing their knowledge – Europe Urban of and insights into urban dynamics in short, thought- provoking pieces. Their essays were collected on the occasion of the adoption of the Pact of Amsterdam with an Urban Agenda for the European Union during the Urban Europe Dutch Presidency of the Council in 2016. The fifty essays gathered in this volume present perspectives from diverse academic disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences. Fifty Tales of the City The authors — including the Mayor of Amsterdam, urban activists, civil servants and academic observers — cover a wide range of topical issues, inviting and encouraging us to rethink citizenship, connectivity, innovation, sustainability and representation as well as the role of cities in administrative and political networks. With the Urban Agenda for the European Union, EU Member States of the city Fifty tales have acknowledged the potential of cities to address the societal challenges of the 21st century. This is part of a larger, global trend. These are all good reasons to learn more about urban dynamics and to understand the challenges that cities have faced in the past and that they currently face. Often but not necessarily taking Amsterdam as an example, the essays in this volume will help you grasp the complexity of urban Europe and identify the challenges your own city is confronting. Virginie Mamadouh is associate professor of Political and Cultural Geography in the Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam. -

Humour As Resistance a Brief Analysis of the Gezi Park Protest

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS 2 PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS David and Toktamış (eds.) In May and June of 2013, an encampment protesting against the privatisation of an historic public space in a commercially vibrant square of Istanbul began as a typical urban social movement for individual rights and freedoms, with no particular political affiliation. Thanks to the brutality of the police and the Turkish Prime Minister’s reactions, the mobilisation soon snowballed into mass opposition to the regime. This volume puts together an excellent collection of field research, qualitative and quantitative data, theoretical approaches and international comparative contributions in order to reveal the significance of the Gezi Protests in Turkish society and contemporary history. It uses a broad spectrum of disciplines, including Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, Social Psychology, International Relations, and Political Economy. Isabel David is Assistant Professor at the School of Social and Political Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa (University of Lisbon) , Portugal. Her research focuses on Turkish politics, Turkey-EU relations and collective ‘Everywhere Taksim’ action. She is currently working on an article on AKP rule for the Journal of Contemporary European Studies. Kumru F. Toktamış, PhD, is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Depart- ment of Social Sciences and Cultural Studies of Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY. Her research focuses on State Formation, Nationalism, Ethnicity and Collective Action. In 2014, she published a book chapter on ‘Tribes and Democratization/De-Democratization in Libya’. Edited by Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış ‘Everywhere Taksim’ Sowing the Seeds for a New Turkey at Gezi ISBN: 978-90-8964-807-5 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 0 8 9 6 4 8 0 7 5 ‘Everywhere Taksim’ Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. -

We Are Here: Look with Us, Not at Us Notes on Powerless Sovereignty by Jo Van Der Spek for M2M “Alone We Are Nothing.” (Anon

We Are Here: Look with Us, Not at Us Notes on Powerless Sovereignty By Jo van der Spek for M2M “Alone we are nothing.” (anonymous member of We Are Here) Since 2011 irregular migrants, refused asylum seekers, undocumented aliens or whatever they are called, have taken the stage in the Netherlands. In Amsterdam this movement of refugees-on-the- street has a name: We Are Here (WAH http://wijzijnhier.org/who-we-are/) . No longer they are in hiding, no more relying on lawyers or helpers, no more being alone and exposed to all sorts of mistreatment. Out in the open, together, demonstrating and camping, demanding a solution. Demanding normal life. An impossible demand? False hope? Short cut to suicide? Or is WAH the solution? Could the show-‘n’-tell method finally succeed in toppling a deadly pyramid of cold measures? Is society moved enough to move their government, to rewind, undo and recreate another world? A world where no man or woman is illegal, where rich and poor can see through hate and fear, where the tourist is equal to the alien. We Are Here is a radical answer to a brutal denial. It’s NO, NO, NO against GO, GO, GO. Me and my migrant. Quite often people ask me “what is your solution?” Well, let us first understand what is the problem, because the way you define the problem defines the path to any solution. The power to define is at the heart of the struggle of people that are usually (made) invisible, unheard, disposable. Imagine you’re a lucky refugee from Eritrea, Sudan or Syria. -

Squatted Social Centres in England and Italy in the Last Decades of the Twentieth Century

Squatted social centres in England and Italy in the last decades of the twentieth century. Giulio D’Errico Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of History and Welsh History Aberystwyth University 2019 Abstract This work examines the parallel developments of squatted social centres in Bristol, London, Milan and Rome in depth, covering the last two decades of the twentieth century. They are considered here as a by-product of the emergence of neo-liberalism. Too often studied in the present tense, social centres are analysed here from a diachronic point of view as context- dependent responses to evolving global stimuli. Their ‗journey through time‘ is inscribed within the different English and Italian traditions of radical politics and oppositional cultures. Social centres are thus a particularly interesting site for the development of interdependency relationships – however conflictual – between these traditions. The innovations brought forward by post-modernism and neo-liberalism are reflected in the centres‘ activities and modalities of ‗social‘ mobilisation. However, centres also voice a radical attitude towards such innovation, embodied in the concepts of autogestione and Do-it-Yourself ethics, but also through the reinstatement of a classist approach within youth politics. Comparing the structured and ambitious Italian centres to the more informal and rarefied English scene allows for commonalities and differences to stand out and enlighten each other. The individuation of common trends and reciprocal exchanges helps to smooth out the initial stark contrast between local scenes. In turn, it also allows for the identification of context- based specificities in the interpretation of local and global phenomena. -

Divercities-City Book-Istanbul.Pdf

DIVERCITIES Governing Urban Diversity: governing urban diversity Creating Social Cohesion, Social Mobility and Economic Performance in Today’s Hyper-diversified Cities Dealing with Urban Diversity Dealing with This book is one of the outcomes of the DIVERCITIES project. It focuses on the question of how to create social cohesion, social Urban Diversity • mobility and economic performance in today’s hyper-diversified cities. The Case of Istanbul The Case of Istanbul The project’s central hypothesis is that urban diversity is an asset; it can inspire creativity, innovation and make cities more liveable. There are fourteen books in this series: Antwerp, Athens, Ayda Eraydin I˙smail Demirdag˘ Budapest, Copenhagen, Istanbul, Leipzig, London, Milan, Feriha Nazda Güngördü Paris, Rotterdam, Tallinn, Toronto, Warsaw and Zurich. Özge Yersen Yenigün This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under www.urbandivercities.eu grant agreement No. 319970. SSH.2012.2.2.2-1; Governance of cohesion and diversity in urban contexts. DIVERCITIES: Dealing with Urban Diversity The Case of Istanbul Ayda Eraydin I˙smail Demirdag˘ Feriha Nazda Güngördü Özge Yersen Yenigün Governing Urban Diversity: Creating Social Cohesion, Social Mobility and Economic Performance in Today’s Hyper-diversified Cities To be cited as: Eraydın, A., Demirdag˘ , I˙., Güngördü, Lead Partner F.N., and Yenigün, Ö. (2017). DIVERCITIES: Dealing - Utrecht University, The Netherlands with Urban Diversity – The case of Istanbul. Middle East Technical University, Ankara. Consortium Partners - University of Vienna, Austria This report has been put together by the authors, - University of Antwerp, Belgium and revised on the basis of the valuable comments, - Aalborg University, Denmark suggestions, and contributions of all DIVERCITIES - University of Tartu, Estonia partners. -

Public Hearing Before SENATE COMMUNITY and URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE

Public Hearing before SENATE COMMUNITY AND URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE SENATE BILL No. 1675 (Concerns municipal authority to deal with abandoned properties; establishes pilot program) SENATE BILL No. 1676 (Revises receivership statutes) LOCATION: Verizon Building DATE: October 10, 2002 Irvington, New Jersey 10:00 a.m. MEMBERS OF COMMITTEE PRESENT: Senator Ronald L. Rice, Co-Chair Senator Barbara Buono Senator Gerald Cardinale ALSO PRESENT: Assemblyman Craig A. Stanley Hannah Shostack Julius Bailey Magregoir Simeon Office of Legislative Services Senate Democratic Senate Republican Committee Aide Committee Aide Committee Aide Hearing Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Gwendolyn A. Faison Mayor Camden 4 Wayne Smith Mayor Irvington 7 Assemblyman Mims Hackett Jr. District 27, and Mayor Orange 16 Hector M. Corchado Councilman North Ward Newark 20 Robert L. Bowser Mayor East Orange 26 D. Bilal Beasley Councilman Irvington 31 Niathan Allen, Ph.D. Director Economic and Housing Development Newark 36 Patrick Morrissy Executive Director HANDS, Inc., and Co-Founder Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey 48 Mitchell Silver Business Administrator Irvington 53 TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page Sandy Accomando Chairperson New Jersey Alliance for the Homeless 61 Prentiss E. Thompson Director Housing Services Irvington 64 Richard Cammarieri Representing New Community Corporation, and Executive Committee -

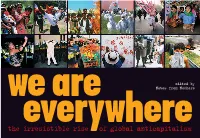

The Irresistible Rise of Global Anticapitalism for Struggling for a Better World All of Us Are Fenced In, Threatened with Death

edited by we are Notes from Nowhere everywhere the irresistible rise of global anticapitalism For struggling for a better world all of us are fenced in, threatened with death. The fence is reproduced globally. In every continent, every city, every countryside, every house. Power’s fence of war closes in on the rebels, for whom humanity is always grateful. But fences are broken. The rebels, whom history repeatedly has given the length of its long trajectory, struggle and the fence is broken. The rebels search each other out. They walk toward one another. They find each other and together break other fences. First published by Verso 2003 The texts in this book are copyleft (except where indicated). The © All text copyleft for non-profit purposes authors and publishers permit others to copy, distribute, display, quote, and create derivative works based upon them in print and electronic 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 format for any non-commercial, non-profit purposes, on the conditions that the original author is credited, We Are Everywhere is cited as a source Verso along with our website address, and the work is reproduced in the spirit of UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG the original. The editors would like to be informed of any copies produced. USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606 Reproduction of the texts for commercial purposes is prohibited www.versobooks.com without express permission from the Notes from Nowhere editorial collective and the publishers. All works produced for both commercial Verso is the imprint of New Left Books and non-commercial purposes must give similar rights and reproduce the copyleft clause within the publication.