ODE 1196-2 DIGITAL V3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos

Olli Mustonen Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 5 SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891–1953) Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 33:55 1 I Andantino 11:57 2 II Scherzo. Vivace 2:59 3 III Intermezzo. Allegro moderato 7:04 4 IV Finale. Allegro tempestoso 11:55 Piano Concerto No. 5 in G major, Op. 55 23:43 5 I Allegro con brio 5:15 6 II Moderato ben accentuato 4:02 7 III Toccata. Allegro con fuoco 1:58 8 IV Larghetto 6:27 9 V Vivo 6:01 OLLI MUSTONEN, piano Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra HANNU LINTU, conductor 3 Prokofiev Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 5 Honestly frank, or just plain rude? Prokofiev was renowned for his uncompromisingly direct behaviour. On one occasion he berated a famous singer saying – within the hearing of her many admirers – that she understood nothing of his music. Seeing her eyes brim, he mercilessly sharpened his tongue and humiliated her still further: ‘All of you women take refuge in tears instead of listening to what one has to say and learning how to correct your faults.’ One of Prokofiev’s long-suffering friends in France, fellow Russian émigré Nicolas Nabokov, sought to explain the composer’s boorishness by saying ‘Prokofiev, by nature, cannot tell a lie. He cannot even say the most conventional lie, such as “This is a charming piece”, when he believes the piece has no charm. […] On the contrary he would say exactly what he thought of it and discuss at great length its faults and its qualities and give valuable suggestions as to how to improve the piece.’ Nabokov said that for anyone with the resilience to withstand Prokofiev’s gruff manner and biting sarcasm he was an invaluable friend. -

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER the STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair

SYDNEY SYMPHONY Photo: Photo: Jamie Williams UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA PROGRAM Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian, 1906–1975) SYDNEY Festive Overture SYMPHONY John Williams (American, born 1932) Hedwig’s Theme from Harry Potter UNDER THE Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian, 1756–1791) Finale from the Horn Concerto No.4, K.495 STARS Ben Jacks, horn SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA THE CRESCENT Hua Yanjun (Chinese, 1893–1950) PARRAMATTA PARK Reflection of the Moon on the Lake at Erquan 8PM, 19 JANUARY 120 MINS John Williams Highlights from Star Wars: Imperial March Benjamin Northey conductor Cantina Music Diana Doherty oboe Main Title Ben Jacks horn INTERVAL Sydney Symphony Orchestra Gioachino Rossini (Italian, 1792–1868) Galop (aka the Lone Ranger Theme) from the overture to the opera William Tell Percy Grainger (Australian, 1882–1961) The Nightingale and the Two Sisters from the Danish Folk-Song Suite Edvard Grieg (Norwegian, 1843–1907) Highlights from music for Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt: Morning Mood Anitra’s Dance In the Hall of the Mountain King Ennio Morricone (Italian, born 1928) Theme from The Mission Diana Doherty, oboe Josef Strauss (Austrian, 1827–1870) Music of the Spheres – Waltz Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840–1893) 1812 – Festival Overture SYDNEYSYDNEY SYMPHONY SYMPHONY UNDER UNDER THE STARS THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair Benjamin Northey is Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Diana Doherty joined the Sydney Symphony Orchestra as Symphony Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the Principal Oboe in 1997, having held the same position with Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. -

Kaapo Johannes Ijas B

CV Kaapo Johannes Ijas b. 26.07.1988 Solvikinkatu 13 C 38 00990 Helsinki +358 44 5260788 [email protected] www.kaapoijas.com Kaapo Ijas (b.1988) is the Mills Williams Junior Fellow in Conducting at the Royal Northern College of Music. He has been fiercely interested in composing, performance, drama, group dynamics and the orchestra itself for all his life. In 2012 it lead him to conducting studies first in Sibelius Academy then Zürcher Hochschule der Künste and ultimately Royal College of Music in Stockholm where he graduated from in spring of 2017. His teachers during his studies and masterclasses include Jorma Panula, Johannes Schlaefli, Jaap van Zweden, Riccardo Muti, Esa-Pekka Salonen, David Zinman, Neeme and Paavo Järvi and Atso Almila. Ijas has conducted i.a. Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Norrköping SO, South Jutland SO, Musikkollegium Winterthur, Gävle Symfoniorkester, Kurpfälzisches Kammerorchester (Mannheim), Hradec Kralove Philharmonia, KMH Symphony Orchestra, Seinäjoki City Orchestra, KammarensembleN, Norrbotten NEO, Swedish Army Band, Helsinki Police band and numerous other project ensembles and choirs during masterclasses and in concerts. Ijas has been invited to various prestigious masterclasses including Gstaad Menuhin Festival 2018 with Jaap van Zweden, Riccardo Muti Opera Academy 2017 in Ravenna, the 8th Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich masterclass with David Zinman in 2017 and Järvi Academy with Paavo and Neeme Järvi in 2016. He was semifinalist in Donatella Flick Conducting Competition 2016 after invited to the competition with 2 weeks notice and among the top 7 in Cadaqués Conducting Competition 2017. In 2018 Ijas was selected as 24 conductors from 566 applicants to take part in Nikolai Malko competition in Copenhagen and won the 3rd prize in Jorma Panula Conducting Competition in Vaasa. -

THURSDAY SERIES 7 John Storgårds, Conductor Golda

2.3. THURSDAY SERIES 7 Helsinki Music Centre at 19.00 John Storgårds, conductor Golda Schultz, soprano Ernest Pingoud: La face d’une grande ville 25 min 1. La rue oubliée 2. Fabriques 3. Monuments et fontaines 4. Reclames lumineuses 5. Le cortege des chomeurs 6. Vakande hus 7. Dialog der Strassenlaternen mit der Morgenröte W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Misera, dove son” 7 min W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Vado, ma dove” 4 min W. A. Mozart: Aria “Non più di fiori” 9 min from the opera La clemenza di Tito INTERVAL 20 min John Adams: City Noir, fpF 30 min I The City and its Double II The Song is for You III Boulevard Nighto Interval at about 20.00. The concert ends at about 21.00. 1 ERNEST PINGOUD rare in Finnish orchestral music, as was the saxophone that enters the scene a (1887–1942): LA FACE moment later. The short, quick Neon D’UNE GRANDE VILLE Signs likewise represents new technol- ogy: their lights flicker in a xylophone, The works of Ernest Pingoud fall into and galloping trumpets assault the lis- three main periods. The young com- tener’s ears. The dejected Procession of poser was a Late-Romantic in the spirit the Unemployed makes the suite a true of Richard Strauss, but in the 1910s he picture of the times; the Western world turned toward a more animated brand was, after all, in the grips of the great of Modernism inspired by Scriabin and depression. Houses Waking provides a Schönberg. In the mid-1920s – as it glimpse of the more degenerate side happened around the time the days of urban life, since the houses are of of the concert focusing on a particular course brothels in which life swings composer began to be numbered – he to the beat of a fairly slow dance-hall entered a more tranquil late period and waltz. -

The Conductor As Part of a Creative Process

Kurs: DG1007 Examensarbete 15 hp (2016) Konstnärligt kandidatprogram i dirigering (Orkester) 180 hp Institutionen för komposition, dirigering och musikteori Handledare: B. Tommy Andersson Markus Luomala The conductor as part of a creative process Case: Students composing for a student orchestra Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt arbete Det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat på inspelning: xxx Table of contents Background ........................................................................................................... 1 Examination concert........................................................................................ 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 3 Work with student orchestras .......................................................................... 3 Shared leadership ............................................................................................ 4 Creativity......................................................................................................... 6 The Project ............................................................................................................ 8 1 Working with the composition students....................................................... 8 The schedule for the composers..........................................................................................9 Student A.............................................................................................................................9 -

“EL ESCORIAL”. SAN LORENZO DEL ESCORIAL (MADRID-SPAIN); 2017, JULY 3Rd-16Th with Prof

VI INTERNATIONAL CONDUCTORS MASTERCLASS “EL ESCORIAL”. SAN LORENZO DEL ESCORIAL (MADRID-SPAIN); 2017, JULY 3rd-16th with Prof. JORMA PANULA & ATSO ALMILA 1. General information Jorma Panula is one of the most recognized and admired teaching conductors today. Known as “maestro of maestros”, he trained several famous conductors, such as Esa-Pekka Salonen, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Osmo Vänska, Petri Sakari, Sakari Oramo, Atso Almila, among others. Maestro Panula has been a professor of Sibelius Academy and the Copenhagen Royal Academy. Today Jorma Panula is a guest conductor and a professor of conducting courses all over the world, in places such as Tanglewood, Aspen, Vaasa (Finland), Moscow, Paris, Australia, Holland and Spain. Atso Almila is composer, conductor, professor of Conducting and Orchestra Schooling. Jorma Panula's student at the Sibelius-Academy 1974-77. Almila has been worked as Music Chief of the Finnish National Theatre, Conductor of Tampere Philharmonic, of Joensuu Orchestra, of Kuopio Orchestra and principal guest of Seinäjoki Orchestra. Teacher of conducting at the Sibelius-Academy 1991-2010 and Professor of Conducting and Orchestral Education from August 2013. Furthermore, he usually teaches Master Classes in China, Finland, Ireland and Switzerland. The masterclass will take place in the Hotel Miranda & Suizo, located in the historic center of San Lorenzo del Escorial (Madrid – Spain), in front of the emblematic Monastery built by Philip the Second at the end of the XVIth century (see http://www.mirandasuizo.com/portada). There will be two sessions with two different groups of participants, in each of which will be worked with one of the teachers: Group A) July 3rd-9th, with Atso Almila Group B) July 10th-16th, with Jorma Panula Conditions and schedule for each session will be developed in the same terms (please see schedule below), while the requirement level will be higher in the Group B. -

Mozart & Shostakovich

CONCERT PROGRAM April 10-11, 2015 Hannu Lintu, conductor Jonathan Chu, violin Beth Guterman Chu, viola MOZART Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major for Violin, Viola, and (1756-1791) Orchestra, K. 364 (1779-80) Allegro maestoso Andante Presto Jonathan Chu, violin Beth Guterman Chu, viola INTERMISSION SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 8 in C minor, op. 65 (1943) (1906-1975) Adagio Allegretto Allegro non troppo— Largo— Allegretto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors series. These concerts are presented by Thompson Coburn LLP. Hannu Lintu is the Felix and Eleanor Slatkin Guest Artist. The concert of Friday, April 10, includes free coffee and doughnuts provided through the generosity of Krispy Kreme. The concert of Saturday, April 11, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Marjorie M. Ivey. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Link Auction Galleries and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 FROM THE STAGE Beth Guterman Chu, Principal Viola, on Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante: “Mozart wrote for the viola tuned up a half step, so the viola is playing in D major instead of E-flat, which makes the passagework easier and makes for a brighter sound. Musicians stopped because violists got better. We can play E-flat without the tuning. I know of only one recording where it is done. I’m sure it changes the sound of the piece as we know it, with all open strings. “There are two deterrents for playing Mozart’s way. -

Sydney Symphony Under the Starssydney Symphony Under the Stars

SYDNEY SYMPHONY Photos: Victor Photos: Frankowski UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA PROGRAM SYDNEY Ludwig van Beethoven (German, 1770–1827) SYMPHONY Fidelio: Overture Bedřich Smetana (Czech, 1824–1884) UNDER THE Má Vlast: Vltava (The Moldau) STARS John Williams (American, born 1932) SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA AND Theme from Schindler's List PARRAMATTA PARK TRUST | AUSTRALIA Sun Yi, violin THE CRESCENT PARRAMATTA PARK Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840–1893) 18 JANUARY The Nutcracker: Three Dances 120 MINS Alexander Borodin (Russian, 1833–1887) Benjamin Northey conductor Prince Igor: Polovtsian Dances Sun Yi violin Leah Lynn cello INTERVAL Sydney Symphony Orchestra Giuseppe Verdi (Italian, 1813–1901) The Force of Destiny: Overture Aram Khachaturian (Armenian, 1903–1978) Spartacus: Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia Camille Saint-Saëns (French, 1835–1921) (orch. Vidal) Carnival of the Animals: The Swan Leah Lynn, cello Jacques Offenbach (German-French, 1819–1880) (arr. Binder) Orpheus in the Underworld: Can-Can Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840–1893) 1812 – Festival Overture SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARSSYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY SUN YI CONDUCTOR VIOLIN Associate Concertmaster Benjamin Northey is Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Sun Yi was born in Hunan, China. He attended the Symphony Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music from 1988 to 1993 Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. He was previously where he was the Concertmaster for the Youth Orchestra Resident Guest Conductor of the Australia Pro Arte and Chamber Orchestra. In 1990, he won the third Chamber Orchestra (2002–2006) and Principal prize for the senior section in the China National Violin Conductor of the Melbourne Chamber Orchestra (2007– Competition, and also participated in the International 2010). -

FRIDAY SERIES 6 Hannu Lintu, Conductor Augustin Hadelich

23.11. FRIDAY SERIES 6 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 Hannu Lintu, conductor Augustin Hadelich, violin Pelageya Kurennaya, sopranoe Henri Dutilleux: L’arbre des songes 25 min 1. Librement, Interlude 2. Vif, Interlude 2 3. Lent, Interlude 3 4. Large et animé. INTERVAL 20 min Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major 58 min I. Bedächtig, nicht eilen II. In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast III. Ruhevoll, poco adagio IV. Sehr behaglich Also playing in this concert will be five students from the Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, chosen for the Helsinki Music Centre’s Orchestra Academy: Andrew Ng, violin I, Elizabeth Stewart, violin 2, Anna-Maria Viksten, viola, Basile Ausländer, cello, and Kaapo Kangas, double bass. The Helsinki Music Centre Orchestra Academy is a joint venture by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, the FRSO and the Sibelius Academy aiming at training that is of an increasingly high standard and with a more practical and international orientation. Players, conductors and composers take part in the project under professional guidance. The Orchestra Academy started up in autumn 2015.. Interval at about 19:40. The concert will end at about 21:15. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and streamed at yle.fi/areena.Dutilleux’s L’arbre des songes will be shown in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 10.2. with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 16.2. 1 HENRI DUTILLEUX The concerto falls into four main sec- tions joined by three interludes looking (1916–2013): VIOLIN back to the one just ended and ahead CONCERTO L'ARBRE to the one to follow. -

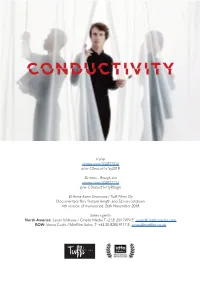

Trailer Vimeo.Com/302877016 P/W: C0nduct1v1ty2018 20 Mins

Trailer vimeo.com/302877016 p/w: C0nduct1v1ty2018 20 mins - Rough cut vimeo.com/302877713 p/w: C0nduct1v1tyR0ugh © Anna-Karin Grönroos / Tuffi Films Oy Documentary film, feature length and 52 min cutdown 4th version of manuscript, 26th November 2018 Sales agents North America: Jason Ishikawa / Cinetic Media T: (212) 204 7979 E: [email protected] ROW: Vesna Cudic / MetFilm Sales T: +44 20 8280 9117 E: [email protected] LOGLINE Sibelius Academy in Finland is the training ground for the future superstar conductors. What does it take to lead an orchestra and who’s got what it takes? SYNOPSIS Conductivity is a film about creative leadership and growing to become a leader. The three main characters are I-Han Fu from Taiwan, Emilia Hoving from Finland and James Kahane from France. They study orchestral conduction in the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, Finland. We follow their journey from being a student to world class artist during three years. It’s a rocky road, where tension, social fears and elements out of their control can create insurmountable obstacles. Our French student James is focused on networking and getting to know people in the industry. During his studies at the Academy he becomes more and more confident, to the point that he gets in trouble for his arrogant style. However, most of the time this feature works in his favour. He is a bit of an opportunist and knows it himself. Our Finnish student Emilia decided to study conducting because she wanted to work with people. But now she has understood, that the work of a conductor is in many ways very lonely. -

Elisa Talvitie Biography Conductor

ELISA TALVITIE BIOGRAPHY CONDUCTOR (917) 783-0797 [email protected] elisatalvitie.com Finnish-American, New York based conductor, ELISA TALVITIE, has gained recognition among orchestras for her dedicated artistry and dynamic leadership. Her detailed musical crafts- manship and broad scholarly perspective to the art form have inspired professionals, concert audiences and aspiring student musicians in Finland, around Europe and in the United States. Elisa Talvitie will make her recording and performance debut with Tacoma Symphony Chamber Orchestra in June 2021. The program consists of newly commissioned compositions by young American and international composers. Before Covid Pandemic halted all performance activities in the U.S. and elsewhere, Elisa Talvitie had received invitations to work with Fargo- Moorhead Symphony Orchestra, ND professional ensemble, and with Concordia College Orchestra, MN, as well as Lake Geneva Symphony Orchestra, WI. These collaborations have been postponed to spring 2022 while Elisa is currently actively engaging herself with the newly forged online music community, holding virtual performances and participating in online seminars, master classes and conferences with colleagues from around the world. Two-time featured guest conductor at Multicultural Sonic Evolution (MuSE), New York City musician and performing artist collective supporting contemporary performance practices and interaction between different fields of art, Elisa Talvitie engaged with the non-profit’s Musikapiphany Orchestra at Sounds of Arts Festival in Queens, NY, and at their 2019 annual concert in Manhattan. In summer 2018 she lead a performance of Stravinsky’s L’Oiseau de Feu Suite with Music in the Alps Festival Orchestra in Austria, and worked as assistant conductor in the festival production of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, supporting the work of Grammy nominated maestro Kenneth Kiesler.