Mozart & Shostakovich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos

Olli Mustonen Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 5 SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891–1953) Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 33:55 1 I Andantino 11:57 2 II Scherzo. Vivace 2:59 3 III Intermezzo. Allegro moderato 7:04 4 IV Finale. Allegro tempestoso 11:55 Piano Concerto No. 5 in G major, Op. 55 23:43 5 I Allegro con brio 5:15 6 II Moderato ben accentuato 4:02 7 III Toccata. Allegro con fuoco 1:58 8 IV Larghetto 6:27 9 V Vivo 6:01 OLLI MUSTONEN, piano Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra HANNU LINTU, conductor 3 Prokofiev Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 5 Honestly frank, or just plain rude? Prokofiev was renowned for his uncompromisingly direct behaviour. On one occasion he berated a famous singer saying – within the hearing of her many admirers – that she understood nothing of his music. Seeing her eyes brim, he mercilessly sharpened his tongue and humiliated her still further: ‘All of you women take refuge in tears instead of listening to what one has to say and learning how to correct your faults.’ One of Prokofiev’s long-suffering friends in France, fellow Russian émigré Nicolas Nabokov, sought to explain the composer’s boorishness by saying ‘Prokofiev, by nature, cannot tell a lie. He cannot even say the most conventional lie, such as “This is a charming piece”, when he believes the piece has no charm. […] On the contrary he would say exactly what he thought of it and discuss at great length its faults and its qualities and give valuable suggestions as to how to improve the piece.’ Nabokov said that for anyone with the resilience to withstand Prokofiev’s gruff manner and biting sarcasm he was an invaluable friend. -

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

THURSDAY SERIES 7 John Storgårds, Conductor Golda

2.3. THURSDAY SERIES 7 Helsinki Music Centre at 19.00 John Storgårds, conductor Golda Schultz, soprano Ernest Pingoud: La face d’une grande ville 25 min 1. La rue oubliée 2. Fabriques 3. Monuments et fontaines 4. Reclames lumineuses 5. Le cortege des chomeurs 6. Vakande hus 7. Dialog der Strassenlaternen mit der Morgenröte W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Misera, dove son” 7 min W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Vado, ma dove” 4 min W. A. Mozart: Aria “Non più di fiori” 9 min from the opera La clemenza di Tito INTERVAL 20 min John Adams: City Noir, fpF 30 min I The City and its Double II The Song is for You III Boulevard Nighto Interval at about 20.00. The concert ends at about 21.00. 1 ERNEST PINGOUD rare in Finnish orchestral music, as was the saxophone that enters the scene a (1887–1942): LA FACE moment later. The short, quick Neon D’UNE GRANDE VILLE Signs likewise represents new technol- ogy: their lights flicker in a xylophone, The works of Ernest Pingoud fall into and galloping trumpets assault the lis- three main periods. The young com- tener’s ears. The dejected Procession of poser was a Late-Romantic in the spirit the Unemployed makes the suite a true of Richard Strauss, but in the 1910s he picture of the times; the Western world turned toward a more animated brand was, after all, in the grips of the great of Modernism inspired by Scriabin and depression. Houses Waking provides a Schönberg. In the mid-1920s – as it glimpse of the more degenerate side happened around the time the days of urban life, since the houses are of of the concert focusing on a particular course brothels in which life swings composer began to be numbered – he to the beat of a fairly slow dance-hall entered a more tranquil late period and waltz. -

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List FLUTE

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List Please submit additional repertoire, including concertante pieces, to both Dr. Andrizzi and to your respective Department Head for consideration before the application deadline. FLUTE Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto for flute and strings, Op. 45 strings Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto No 2, Op. 111 orchestra Bach, Johann Sebastian: Suite in B Minor BWV1067, Orchestra Suite No. 2, strings Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel: Concerto in D Minor Wq. 22, strings Berio, Luciano: Serenata for flute and 14 instruments Bozza, Eugene: Agrestide Op. 44 (1942) orchestra Bernstein, Leonard: Halil, nocturne (1981) strings, percussion Bloch, Ernest: Suite Modale (1957) strings Bloch, Ernest: "TWo Last Poems... maybe" (1958) orchestra Borne, Francois: Fantaisie Brillante on Bizet’s Carmen orchestra Casella, Alfredo: Sicilienne et Burlesque (1914-17) orchestra Chaminade, Cecile: Concertino, Op. 107 (1902) orchestra Chen-Yi: The Golden Flute (1997) orchestra Corigliano, John: Voyage (1971, arr. 1988) strings Corigliano, John: Pied Piper Fantasy (1981) orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 7 in E Minor, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 10 in D Major, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto in D Major, orchestra Doppler, Franz: Hungarian Pastoral Fantasy, Op. 26, orchestra Feld, Heinrich: Fantaisie Concertante (1980) strings, percussion Foss, Lucas: Renaissance Concerto (1985) orchestra Godard, Benjamin: Suite Op. 116; Allegretto, Idylle, Valse (1889) orchestra Haydn, Joseph: Concerto in D Major, H. VII f, D1 Hindemith, Paul: Piece for flute and strings (1932) Hoover, Katherine: Medieval Suite (1983) orchestra Hovhaness, Alan: Elibris (name of the DaWn God of Urardu) Op. 50, (1944) Hue, Georges: Fantaisie (1913) orchestra Ibert, Jaques: Concerto (1933) orchestra Jacob, Gordon: Concerto No. -

FRIDAY SERIES 6 Hannu Lintu, Conductor Augustin Hadelich

23.11. FRIDAY SERIES 6 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 Hannu Lintu, conductor Augustin Hadelich, violin Pelageya Kurennaya, sopranoe Henri Dutilleux: L’arbre des songes 25 min 1. Librement, Interlude 2. Vif, Interlude 2 3. Lent, Interlude 3 4. Large et animé. INTERVAL 20 min Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major 58 min I. Bedächtig, nicht eilen II. In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast III. Ruhevoll, poco adagio IV. Sehr behaglich Also playing in this concert will be five students from the Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, chosen for the Helsinki Music Centre’s Orchestra Academy: Andrew Ng, violin I, Elizabeth Stewart, violin 2, Anna-Maria Viksten, viola, Basile Ausländer, cello, and Kaapo Kangas, double bass. The Helsinki Music Centre Orchestra Academy is a joint venture by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, the FRSO and the Sibelius Academy aiming at training that is of an increasingly high standard and with a more practical and international orientation. Players, conductors and composers take part in the project under professional guidance. The Orchestra Academy started up in autumn 2015.. Interval at about 19:40. The concert will end at about 21:15. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and streamed at yle.fi/areena.Dutilleux’s L’arbre des songes will be shown in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 10.2. with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 16.2. 1 HENRI DUTILLEUX The concerto falls into four main sec- tions joined by three interludes looking (1916–2013): VIOLIN back to the one just ended and ahead CONCERTO L'ARBRE to the one to follow. -

Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola, and String Ensemble, K

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Edited and reduced by Joshua Dieringer Sinfonia concertante, K.364 (320d) in E-flat Major for Violin, Viola, and String Ensemble (Violin, Viola, and Two Violoncellos) Introduction writing into that characteristic of contemporary 4 chamber music. BACKGROUND PURPOSE OF ARRANGEMENT Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)1 composed his Sinfonia Concertante, K.364 The present new arrangement, scored for solo (320d) at Salzburg around 1779. Few details are violin, solo viola, and a string ensemble of violin, known about the origin of this piece beyond the viola, and two violoncellos, allows the Sinfonia place and date of composition.2 Concertante to be performed as a true soloistic piece while accommodating both the difficulty of Mozart’s choice of a combination of arranging a full orchestra accompaniment and violin and viola as solo instruments for the the shortcomings of piano reductions that concertante group followed naturally from the necessarily miss important melodic and harmonic combination’s popularity in Salzburg at the material. While the instruments involved are time;3 the orchestra section calls additionally for those of the standard string sextet, the editor has two oboes, two horns, and strings. The solo viola renamed the instrumentation to reflect the has a transposing part that specifies scordatura importance of preserving the solo violin and solo tuning up a whole tone, with the likely intent of viola lines. The ensemble material took into brightening the tone and increasing its volume account both the original orchestral parts and and soloistic qualities. decisions made in the 1808 sextet arrangement. The editorial priority lay in preserving as much SEXTET ARRANGEMENT BACKGROUND musical material from the original instrumentation as was feasible, prioritizing the The idea of arranging this piece for string sextet original orchestral balance over a chamber is not new, although the origins of this practice texture. -

FRIDAY SERIES 5 Hannu Lintu, Conductor Li-Wei Qin, Cello

9.11. FRIDAY SERIES 5 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 Hannu Lintu, conductor Li-Wei Qin, cello Witold Lutosławski: Symphony No. 2 30 min Hesitant Direct INTERVAL 20 min Pyotr Tchaikovsky: Variations on a Rococo Theme, 18 min Op. 33 Thema. Moderato assai quasi Andante–Moderato semplice Var. I. Tempo della Thema Var. II. Tempo della Thema Var. III. Andante sostenuto Var. V. Andante grazioso Var. V. Allegro moderato Var. VI. Andante. Var. VII e Coda. Allegro vivo Sergei Prokofiev (arr. Palmer): War and Peace, 26 min symphonic suite I The Ball 1. Fanfare and Polonaise (Maestoso e brioso) 2. Waltz (Allegro ma non troppo) 3. Mazurka (Animato) II Intermezzo – May Night (Andante assai) III Finale 1. Snowstorm (Tempestoso) 2. Battle (Allegro) 3. Victory (Allegro fastoso – Andante maestoso) 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Petri Aarnio, violin Li-Wei Qin, cello Ossi Tanner, piano Pyotr Tchaikovsky: Piano Trio A Minor Op. 50 47 min 1. Pezzo elegiaco 2. Tema con variazioni Interval at about 19:40. The concert will end at about 21:00, the late-night chamber music at about 22:00. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and Yle Areena and later on Yle Teema on 30.12. with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 5.1. 2 WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI of movements. The two movements of roughly the same size achieve bal- (1913–1994): ance but not symmetry, since they dif- SYMPHONY NO. -

ODE 1251-2 DIGITAL.Indd

MESSIAEN TURANGALÎLA- SYMPHONIE Angela Hewitt Valérie Hartmann-Claverie Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra Hannu Lintu OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908–1992) TURANGALÎLA-SYMPHONIE (1946–48) SYMPHONY FOR PIANO, ONDES MARTENOT AND ORCHESTRA (75:03) I Introduction Modéré, un peu vif (6:32) II Chant d’amour (Love song) 1 Modéré, lourd (8:02) III Turangalîla 1 Presque lent, rêveur (5:23) IV Chant d’amour 2 Bien modéré (10:19) V Joie du Sang des Étoiles Vif, passionné avec joie (6:11) VI Jardin du Sommeil d’amour Très modéré, très tendre (9:52) VII Turangalîla 2 Un peu vif, bien modéré (3:52) VIII Développement d’amour Bien modéré (11:37) IX Turangalîla 3 Bien modéré (5:37) X Final Modéré, presque vif, avec une grande joie (7:32) ANGELA HEWITT, piano VALÉRIE HARTMANN-CLAVERIE, ondes Martenot Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra HANNU LINTU, conductor 3 OLIVIER MESSIAEN 4 MESSIAEN: TURANGALÎLA-SYMPHONIE It says much about the music of Olivier Messiaen that, despite the intervening two decades since the composer’s death, his compositions are still played, performed and recorded regularly by some of the greatest living musicians of all ages and nationalities. Born in 1908 in the town of Avignon, the son of a Shakespearean scholar on his father’s side and a well-known poetess on his mother’s, Olivier Messiaen’s early influences must have stemmed in part from that unusually rich, literary and theatrical awareness of his parents. His sensitivity, however, was not limited merely to intellectual pursuits and his lifelong fascination with the natural world also dates from his childhood. -

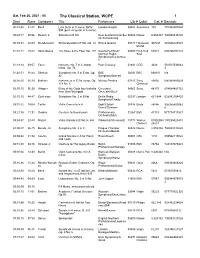

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Feb 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 21:47 Bach Lute Suite in G minor, BWV Gordon Kreplin 05308 Ascencion 103 791022009224 995 (perf. on guitar in A minor) 00:24:1709:56 Mozart, L. Sinfonia in B flat New Zealand Chamber 05006 Naxos 8.553347 730099434720 Orch/Armstrong 00:35:43 24:09 Mendelssohn String Quartet in E flat, Op. 12 Eroica Quartet 05377 Harmonia 907245 093046724528 Mundi 01:01:2215:42 Saint-Saëns The Muse & the Poet, Op. 132 Isserlis/Bell/North 04008 RCA Red 63518 090266351824 German Radio Seal Symphony/Eschenbac h 01:18:1409:07 Fauré Nocturne No. 7 in C sharp Paul Crossley 01881 CRD 3406 501515534062 minor, Op. 74 3 01:28:51 30:44 Sibelius Symphony No. 5 in E flat, Op. BBC 04593 BBC MM103 n/a 82 Symphony/Bamert 02:01:0505:10 Brahms Intermezzo in E flat minor, Op. Murray Perahia 07915 Sony 89856 696998985629 118 No. 6 Classical 02:07:15 06:30 Wagner Entry of the Gods Into Valhalla Cleveland 04563 Sony 48175 074644481752 from Das Rheingold Orchestra/Szell 02:15:1544:47 Zemlinsky Symphony No. 2 in B flat Berlin Radio 02297 London 421 644 028942164420 Symphony/Chailly 03:01:32 19:04 Tartini Violin Concerto in A Ughi/I Solisti 00939 Erato 88096 326965880962 Veneti/Scimone 6 03:21:3611:31 Rossini Overture to Semiramide Philharmonia 01267 EMI 47118 077774711821 Orchestra/Muti 03:34:57 23:40 Mozart Violin Sonata in B flat, K. -

DVOŘÁK Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 14, 2016, 8:00pm Saturday, October 15, 2016, 8:00pm Sunday, October 16, 2016, 3:00pm Hannu Lintu, conductor Alban Gerhardt, cello LUTOSŁAWSKI Chain 3 (1986) (1913-1994) DVOŘÁK Cello Concerto in B minor, op. 104 (1895) (1841-1904) Allegro Adagio, ma non troppo Finale: Allegro moderato Alban Gerhardt, cello INTERMISSION STRAVINSKY Petrushka (1947 version) (1882-1971) The Shrove-Tide Fair— Petrushka— The Moor— The Shrove-Tide Fair and the Death of Petrushka Peter Henderson, piano 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Hannu Lintu is the Essman Family Foundation Guest Artist. Alban Gerhardt is the Jean L. Rainwater Guest Artist. The concert of Friday, October 14, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Margaret P. Gilleo and Charles J. Guenther, Jr. The concert of Saturday, October 15, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. Galvin. The concert of Sunday, October 16, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Ted and Robbie Beaty, in memory of Derek S. Beaty. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of the Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the STL Symphony free mobile app available on iTunes or android. SYMPHONIC DANCES: Fri, Oct 21, 8:00pm Sat, Oct 22, 8:00pm | Sun, Oct 23, 3:00pm Cristian Macelaru, conductor; Orli Shaham, piano BALAKIREV Islamey BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. -

All Mozart with Yannick

23 Season 2019-2020 Thursday, October 10, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Sunday, October 13, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Juliette Kang Violin Choong-Jin Chang Viola Mozart Symphony No. 35 in D major, K. 385 (“Haffner”) I. Allegro con spirito II. Andante III. Menuetto IV. Presto Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 364, for violin, viola, and orchestra I. Allegro maestoso II. Andante III. Presto Intermission Mozart Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 I. Molto allegro II. Andante III. Menuetto (Allegretto)—Trio—Menuetto da capo IV. Allegro assai This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. The October 10 concert is sponsored by an anonymous donor. These concerts are part of The Philadelphia Orchestra’s WomenNOW celebration. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. The app will now automatically advance slides as the live concert progresses. Helpful Hints » You can follow different tracks of content in LiveNote.