Role Name Affiliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

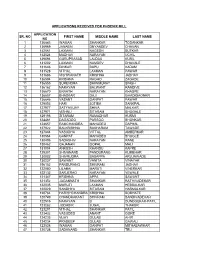

Applications Received for Phoenix Mill

APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR PHOENIX MILL APPLICATION SR. NO FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME NO 1 136843 WAMAN SHANKAR TODANKAR 2 136969 JANABAI DNYANDEV CHAVAN 3 142561 LAXMAN NAGESH BUTKAR 4 142524 MADHAV NARAYAN UCHIL 5 139594 GURUPRASAD LALDAS KURIL 6 131202 LAXMAN NAMDEV DHAVALE 7 131646 DINKAR BAPU KADAM 8 131528 VITHAL LAXMAN PAWAR 9 131686 VISHWANATH KRISHNA JADHAV 10 136594 KRISHNA RAGHO ZAGADE 11 136555 SURENDRA SHIWMURAT SINGH 12 136162 NARAYAN BALWANT RANDIVE 13 136670 EKNATH NARAYAN KHADPE 14 136657 BHASKAR DAJI GHADIGAONKR 15 136646 VASANT GANPAT PAWAR 16 129053 HARI JOTIBA SANKPAL 17 127977 SATYAVIJAY SHIVA MALKAR 18 127971 VISHNU SITARAM BHOGALE 19 129198 SITARAM RAMADHAR KURMI 20 124461 DAGADOO PARSOO BHONKAR 21 124657 RAMCHANDRA MAHADEO DAPHAL 22 127922 BALKRISHNA SAKHARAM TAWADE 23 127844 VASUDHA VITTAL AMBERKAR 24 130564 GANPAT MAHADEO BHOGLE 25 130496 SADASHIV NARAYAN RANE 26 130462 GAJANAN GOPAL MALI 27 131004 ANKUSH KHANDU KAPRE 28 129301 SHIVANAND PANDURANG KUMBHAR 29 130082 SHIVRUDRA BASAPPA ARJUNWADE 30 130237 SAWANT VANITA VINAYAK 31 196102 PANDURANG SHIVRAM JADHAV 32 122080 LILABAI MARUTI VINERKAR 33 122132 SARJERAO NARAYAN YEWALE 34 121347 KRISHNA APPA SAWANT 35 121352 JAGANNATH SHANKAR RATHIVADEKAR 36 122035 MARUTI LAXMAN HEBBALKAR 37 122029 SANDHYA SITARAM HARMALKAR 38 120784 HARISHCHANDRA KRISHNA BOBHATE 39 120749 CHANDRAKANT SHIVRAM BANDIVADEKAR 40 122516 NARAYAN B DUNDGEKAR-PATIL 41 123282 JODHBIR JUGAL THAKUR 42 123201 VITHAL SHANKAR PATIL 43 123432 VASUDEO ANANT GORE 44 124233 VIJAY GULAB AHIR 45 124234 -

Fairs and Festivals, Part VII-B

PRG. 179.11' em 75-0--- . ANANTAPUR CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII-B (10) FAIRS AND F ( 10. Anantapur District ) A. CHANDRA S:EKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Sltl}erintendent of Cens'Us Ope'rations. Andhru Pradesh Price: Rs. 7.25 P. or 16 Sh. 11 d.. or $ 2.fil c, 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PARt II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-1VJ PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IXJ PARt II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Housing Report and Subsidiary Tables PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe5 PART VI Village Survey Monographs (46") PART VII-A (I)) Handicraft Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) J PART VlI-B (1 to 20) Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration "'\ (Not for PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J Sale) PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census Handbooks (Separate Volume for each Dislricf) Plate I: . A ceiling painting of Veerabhadra in Lepakshi temple, Lepakshi, Hindupur Taluk FOREWORD Although since the beginning of history, foreign travellers and historians have recorded the principal marts and entrepots of commerce in India and have even mentioned impo~'tant festivals and fairs and articles of special excellence available in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

O Sai ! Thou Art Our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi Is Our Pandharpur !

O Sai ! Thou art our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi is our Pandharpur ! Shirdi majhe Pandharpur l Sai Baba Ramavar ll 1 ll Shuddha Bhakti Chandrabhaga l Bhav Pundalik jaga ll 2 ll Ya ho ya ho avghejan l Kara Babansi vandan ll 3 ll Ganu mhane Baba Sai l Dhav paav majhe Aai ll In this Abhang, which is often recited as a Prarthana (prayer), Dasganu Maharaj describes that Shirdi is his Pandharpur where his God resides. He calls upon the devotees to come and take shelter in the loving arms of Sai Baba. Situated in the devout destination of Pandharpur is a temple that is believed to be very old and has the most surprising aspects that only the pilgrim would love to feel and understand. This is the place where the devotees throng to have a glimpse of their favourite Lord. The Lord here is seen along with His consort Rukmini (Rama). The impressive Deities in their black colour look very resplendent and wonderful. Situated on the banks of the river Chandrabhaga or Bhima, this place is also known as Pandhari, Pandurangpur, Pundalik kshetra. The Skandha and the Padma puranas refer to places known as Pandurang kshetra and Pundalik kshetra. The Padma puran also mentions Dindiravan, Lohadand kshetra, Lakshmi tirtha, and Mallikarjun van, names that are associated with Pandharpur. The presiding Deity has many different names like Pandharinath, Pandurang, Pandhariraya, Vithai, Vithoba, Vithu Mauli, Vitthal Gururao etc. But, the well-known and commonly used names are Pandurang or Vitthal or Vithoba. The word Vitthal is said to be derived from the Kannad (a language spoken in the southern parts of India) word for Lord Vishnu. -

In the High Court of Karnataka at Bengaluru Dated This the 31St Day of October, 2015 Before the Hon'ble Mr.Justice B.S.Patil C

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 31 ST DAY OF OCTOBER, 2015 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE B.S.PATIL C.R.P.No.219/2012 BETWEEN VASUDEVA PURUSHOTHAM SHENOY S/O LATE PURUSHOTHAMA VITHOBA SHANBHOGUE AGED ABOUT 70 YEARS R/AT HOUSE NO.30, SIDDESHWARA PARK VIDYANAGARA, HUBLI-580031. ... PETITIONER (By Sri.S.K.ACHARYA, ADV.) AND 1. H.KOGGANNA SHENOY AGED ABOUT 86 YEARS S/O MANJUNATHA SHANBHOGUE R/AT HEJAMADI VILLAGE, UDUPI TALUK & DISTRICT 2. SMT. NARASIMHA SHENOY AGED ABOUT 77 YEARS W/O LATE NARASIMHA PURUSHOTHAMA SHENOY 3. JAYA SHENOI AGED ABOUT 57 YEARS 4. POORNIMA RAMAKANTHA NAIK AGED ABOUT 53 YEARS W/O RAMAKANTHA NAIK 2 5. SAVITHA JAYANATHA KAMATH AGED ABOUT 53 YEARS W/O JAYANATH KAMATH RESPS.2 TO 5 R/AT NO.9/271, CENTURY RAYAN COLONY, MURBAD ROAD, SHAHAD-421103 MAHARASHTRA STATE 6. SUMANA D. SHENOY AGED ABOUT 70 YEARS W/O DAYANANDA P. SHENOY 7. PURUSHOTHAMA D. SHENOY AGED ABOUT 57 YEARS S/O DAYANANDA P. SHENOY RESPS.6 & 7 R/AT NO.111, BHUVANENDRA APARTMENT BEHIND C.V. NAIK HALL, MANGALORE, D.K. DISTRICT 8. ARUNA @ VEENA VENKATESH GADIYAR AGED ABOUT 53 YEARS W/O VENKATESH S. GADIYAR R/AT NO.26, FLAT NO.106, 1ST FLOOR, YOGI NAGAR, EKASR RAOD, BARIVELI WEST MUMBAI-92 9. SATYAVATHI SHENOY AGED ABOUT 72 YEARS W/O MOHANDAS PURUSHOTHAMA 10. SUNIL MOHAN SHENOY AGED ABOUT 46 YEARS S/O MOHANDAS PURUSHOTHAMA SHENOY 11. HEMA MOHAN DAS SHANBHOGUE S/O MOHANDAS PURUSHOTHAMA SHENOY AGED ABOUT 40 YEARS R/AT MUDA FLAT NO.15, PRASHANTH NAGAR,MAIN ROAD, BEHIND DERE BAIL CHURCH, MANGALORE-06 3 12. -

Precure History

History (PRE-Cure) June 2019 - March 2020 Visit our website www.sleepyclasses.com or our YouTube channel for entire GS Course FREE of cost Also Available: Prelims Crash Course || Prelims Test Series Table of Contents 1. Srirangam Ranganathaswamy Temple Tiruchirapalli ............................................................1 2. Losar Bahubali, Khajuraho ...............................................................................................................2 3. Khajuraho Temples ..............................................................................................................................3 4. Jagannath Temple ................................................................................................................................4 5. Madhubani Paintings ..........................................................................................................................6 6. Adilabad Dhokra Warangal Dhurries Monument Mitras ....................................................7 7. GI Tags ......................................................................................................................................................8 8. Adopt a Heritage ..................................................................................................................................8 9. Bhakti Movement ................................................................................................................................9 10. Bhakti Saints ..........................................................................................................................................11 -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance. -

Eligible Candidates

List of Applicants Found Eligible for Re-Draw for Selection of LPG Distributor Name of Area/ Territory/ Regional Office: Wai LPG Territory (BPC) Name of Location: SHAHPUR -ICHALKARANJI Category: SC Oil Company: BPC Type of Distributorship: RURBAN Name of District: KOLHAPUR MKT Plan: Against Termination S.NO. NAME OF PERSON FATHER / HUSBAND'S NAME APPLICATION REFERENCE NO. 1 AJAY ASHOK KAMBLE ASHOK AKARAM KAMBLE BPC03408018027082019 2 SANJAY ASHOK KAMBLE ASHOK AKARAM KAMBLE BPC03408018127082019 3 GEETA GANESH KHANDEKAR GANESH BAJIRAO KHANDEKAR BPC03408019414092019 4 MANGESH SHAHAJI KAMBLE SHAHAJI ANANDA KAMBLE BPC03408018228082019 5 GANESH ASHOK KAMBLE ASHOK GANPATI KAMBLE BPC03408018328082019 6 NIKET GAUTAM KAMBLE GAUTAM BALVANT KAMBLE BPC03408023217092019 7 NITIN VIJAY MANE VIJAYKUMAR GANPATI MANE BPC03408018429082019 8 MAYUR SHIVAJI AWALE SHIVAJI VISHNU AWALE BPC03408018602092019 9 PRITAM BABASAHEB MANE BABASAHEB BHAGWAN MANE BPC03408018705092019 10 SMITA DIPAK BHOSALE PRABHAKAR MAHIPATI MANE BPC03408018809092019 11 RAGHAVENDRA TANAJI KAMBLE TANAJI KESHAV KAMBLE BPC03408023618092019 12 AMRUTA AMAR PUJARI AMAR TANAJI PUJARI BPC03408023518092019 13 SAGAR PANDIT CHANDANE PANDIT LAXMAN CHANDANE BPC03408023317092019 14 POOJA RAJARAM LOKARE RAJARAM SIDDHU LOKARE BPC03408019012092019 15 RAMESH ISHWAR MALAGI ISHWAR RAMAPPA MALAGI BPC03408019112092019 16 RAVINDRA VISHWANATH VIRKAR VISHWANATH RAMCHANDRA BPC03408019614092019 VIRKAR 17 RUPALI RAHUL GAIKWAD RAHUL ROHIDAS GAIKWAD BPC03408023918092019 18 SANTOSHI MALLU BENADE MALLU JINAPPA BENADE -

The Vithoba Temple of Pan<Jharpur and Its Mythological Structure

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 19S8 15/2-3 The Vithoba Faith of Mahara§tra: The Vithoba Temple of Pan<Jharpur and Its Mythological Structure SHIMA Iwao 島 岩 The Bhakti Movement in Hinduism and the Vithobd Faith o f MaM rdstra1 The Hinduism of India was formed between the sixth century B.C. and the sixth century A.D., when Aryan Brahmanism based on Vedic texts incor porated non-Aryan indigenous elements. Hinduism was established after the seventh century A.D. through its resurgence in response to non-Brah- manistic traditions such as Buddhism. It has continuously incorporated different and new cultural elements while transfiguring itself up to the present day. A powerful factor in this formation and establishment of Hinduism, and a major religious movement characteristic especially of medieval Hin duism, is the bhakti movement (a religious movement in which it is believed that salvation comes through the grace of and faith in the supreme God). This bhakti movement originated in the Bhagavad GUd of the first century B.C., flourishing especially from the middle of the seventh to the middle of the ninth century A.D. among the religious poets of Tamil, such as Alvars, in southern India. This bhakti movement spread throughout India through its incorporation into the tradition of Brahmanism, and later developed in three ways. First, the bhakti movement which had originated in the non-Aryan cul ture of Tamil was incorporated into Brahmanism. Originally bhakti was a strong emotional love for the supreme God, and this was reinterpreted to 1 In connection with this research, I am very grateful to Mr. -

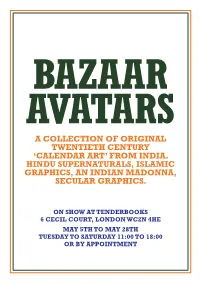

Bazaar Avatars a Collection of Original Twentieth Century ‘Calendar Art’ from India

BAZAAR AVATARS A COLLECTION OF ORIGINAL TWENTIETH CENTURY ‘CALENDAR ART’ FROM INDIA. HINDU SUPERNATURALS, ISLAMIC GRAPHICS, AN INDIAN MADONNA, SECULAR GRAPHICS. ON SHOW AT TENDERBOOKS 6 CECIL COURT, LONDON WC2N 4HE MAY 5TH TO MAY 28TH TUESDAY TO SATURDAY 11:00 TO 18:00 OR BY APPOINTMENT 10. C.S. Ananth & J. Raj –Jay Gange Mata (Hail Mother Ganges) HINDU SUPERNATURALS; 1–45 THE PANTHEON OF GODS, GOD-MEN, GURUS, PILGRIMAGE SITES, AND SCENES FROM THE EPICS ISLAMIC GRAPHICS 46–49 AN INDIAN MADONNA 50 SECULAR GRAPHICS 51–58 BAZAAR AVATARS ‘Avatars’ because some Hindus believe that the image (‘arca’ in Sanskrit) you’ve never heard of and that was once called ‘mini Japan’ by Nehru.They of their god is an actual incarnation or ‘avatara’ of Vishnu. Most probably were essentially a byproduct of the need for decorative labels for believe that images, even ones made in cheap, huge runs like calendar fireworks, a business in which the enterprising Nadar caste in Sivakasi prints, offer a way to access the gods or at least worship them. Nearly were pioneers. 80% of Indians are Hindus, which probably means that more than a billion Roots go deep, in terms of style, aesthetics and the way they are people worldwide believe to some extent that ‘arcas’ are the way to their manufactured, they are related to the Kalighat paintings of the Patuas of ‘avataras’. For Hindus, they are ‘darshan’ or an auspicious sight of the holy West Bengal that spanned the early nineteenth to early twentieth deity that reflects back on the observer.The holy being transmigrates into centuries. -

CHAPTER 7- Religion and Gods of Maharashtra

Tran DF sfo P rm Y e Y r B 2 B . 0 A Click here to buy w w m w co .A B BYY. CHAPTER 7—RELIGION AND GODS OF MAHARASHTRA IN MAHARASHTRA A MAJORTY OF PEOPLE OF ALL CASTES worship as family deity either one or two of the following Gods : (1) The Mother—goddess. (2) Shiva (3) Khandoba. The fourth God is Vithoba. He is worshipped and revered by most Marathi people but he is not the family deity of many families. Another very popular God is Maruti. The God is known as “ Hanumanta” in Maharashta, Karnatak and Andhra Pradesh, as “ Anjaneya “ in Tamilnad and “ Mahabir “ in the north. He is, however, never a family deity. Other Gods, besides these, are Vishnu, with his incarnations of Ram, Krishna, Narsimha, in rare cases Vamana, A count taken while doing field work in Satara showed that only a minority of people belonging to Brahmin, Maratha, and Mali castes claimed Rama, Krishna, Narsimha as their family deities. Of these again a small number only are worshippers of Narsimha. Narsimha used to be not an uncommon given name in Andhra, Karnatak and Maharashtra1. Dr. S. V. Ketkar wrote that there was an ancient King of Maharashtra called Narsimha perhaps then as later, parts of Maharashtra, Andhra and Karnatak were under one rule. The name would change to Narsu or Narsia in common parlance. It is possible that Narsimha was a legendary hero in this area. He is also connected in a legend of the Chenchu, a tribe from Andhra. People worship many gods Worshippers of Shiva also worship Vishnu. -

Mhada Mill Worker Lottery - MILLLOTTERY - MILL WORKER LOTTERY 2012

Mhada Mill Worker Lottery - MILLLOTTERY - MILL WORKER LOTTERY 2012 Mill: 8-INDIA_UNITED_2 {INDIA UNITED MILL NO.2} Winner List Priority No. Mill Worker Name Application Form Number / Numbers Flat 1 VIJAY JAGNNATH FADTARE 95359 1, F, 1, 101 2 SHANTARAM TUKARAM NIRMAL 406279 1, F, 2, 201 3 ASHOK JAGANNATH POTEKAR 300537 1, F, 2, 202 4 KRISHNA NARAYAN GHARAL 416168 1, F, 2, 203 5 BALKRISHNA DHONDIBA PAWAR 7583 1, F, 2, 204 6 SHANTARAM PUNDALIK MAYEKAR 93343 1, F, 2, 205 7 GANPAT RAMCHANDRA CHAVAN 26597 1, F, 2, 206 8 ANIL VIRJI SOLANKI 89511 1, F, 2, 207 9 CHANDRAKANT NARAYAN SATVILKAR 69838 1, F, 2, 208 10 PANDURANG SITARAM JADHAV 425539 1, F, 2, 209 11 PANDURANG HARI PARWADI 16105 1, F, 2, 210 12 RAM SOPAN GHULE 21103 1, F, 2, 211 13 SARERAO BAJARANG MANE 48067 1, F, 2, 212 14 ANKUSH RAJARAM NAWADKAR 39228 1, F, 3, 301 15 MAHADEO RAVJI PAWAR 56124 1, F, 3, 302 16 VITHOBA JAGANNATH POL 74863 1, F, 3, 303 17 DASHRATH GAINAJEE KALBHOR 52891 1, F, 3, 304 18 VISHWANATH DEWOO SAWANT 416295 1, F, 3, 305 19 RAMCHANDRA YASHWANT PHEPADE 48912 1, F, 3, 306 20 PANDURANG CHANDU YADAV 11721 1, F, 3, 307 21 ARJUN RAMCHANDRA NATEKAR 15528 1, F, 3, 308 22 HARIDAS NARAYAN PADIYAR 27125 1, F, 3, 309 23 DATTARAM TUKARAM SHETYE 20864 1, F, 3, 310 24 SHUBHANGI SURYAKANT PATKAR 136972 1, F, 3, 311 25 KISAN MARUTI HARPUDE 431988 1, F, 3, 312 26 MAHIPAT BABOO KADAM 13411 1, F, 4, 401 27 KASHINATH RAMCHANDRA RAHATE 51955 1, F, 4, 402 28 RAMESH MOTIRAM GAWDE 77358 1, F, 4, 403 29 RANGNATH LAXMAN MANDAWKAR 88036 1, F, 4, 404 30 PARWATY DATTARAM PAWAR 123900 1, F,