Stranger and Stranger: Creating Theory Through Ethnographic Distance And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Press of Kansas

CultureAmerica Reinventing Richard Nixon A Cultural History of an American Obsession Daniel Frick “Senator Bob Dole argued that the last half of the twentieth century was ‘the age of Nixon’ and Daniel Frick shows us why. The Nixon limned here is a mutable public figure constantly reinterpreted by his enemies and his admirers. They all find him an irresistible figure for thinking about who we are, who we want to be, and what we’re willing to do to get there. It is a brilliant and scary read.” —David Farber, author of The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s “All the cultural renderings of Nixon you might ever wish to explore are provocatively analyzed here.”—David Greenberg, author of Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image 336 pages, 45 illustrations, Cloth $34.95 Weather Matters An American Cultural History since 1900 Bernard Mergen “The definitive weather book for decades to come. From weather humor to the politics of weather disaster with Katrina, from weather lore to weather prediction, from weather watchers to weather consumers, this book offers a truly comprehensive and invaluable history of weather’s enormous social and cultural impact.”—Marita Sturken, author of Desiring the Weather and Tourists of History “Mergen may know more about the cultural history of weather than anyone around and his latest book overflows with fascinating discussions.”—Gary Alan Fine, author of Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction 448 pages, 22 illustrations, Cloth $34.95 University Press of Kansas Phone (785) 864-4155 • Fax (785) 864-4586 www.kansaspress.ku.edu American Angels Useful Spirits in the Material World Peter Gardella “Written in a sprightly style, with an eye to pop culture, this is the first study to describe the profoundly important role that angels play in the religious imagination. -

Download Download

Volume 22, No. 1, Art. 8 January 2021 Tiny Publics and Social Worlds—Toward a Sociology of the Local Gary Alan Fine in Conversation With Reiner Keller Key words: Abstract: Gary Alan FINE is among the most prominent figures in contemporary sociological collective ethnography worldwide. In this conversation, he talks about influences in his academic career and memories; culture; key intellectual choices. Considered to be a "serial ethnographer" who has worked in multiple ethnography; settings, his work focuses on small groups and peopled ethnography, as well as on rumors, gossip, group; interaction; and moral story telling in tiny and larger publics. FINE describes his core theoretical interest as narrative; rumor; residing in the interplay of structure, interaction, and culture and discusses the multiple local ways social theory; society is realized by people in formal and informal social settings: ranging from baseball teams, social worlds; restaurant kitchens, weather reporting to chess players—to name but a few research sites. structure Influenced by symbolic interactionist thinking and other important approaches to social worlds, he argues for a confident voice of ethnographic research and writing as well as the importance of conceptual work in a theory-informed empirical sociology of what people do together. Table of Contents 1. Starting Out With a Blend of Inspirations 2. A Sociological Trinity: Structure, Interaction, Culture 3. Morel Tales: About Peopled Ethnography 4. The Case for a Grounded Sociology 5. Too Much Knowledge Is a Dangerous Thing (for a Serial Ethnographer) 6. Moral Tales: The Worst President in American History 7. The Authority of an Ethnographer 8. -

WHITNEY JOHNSON University of Chicago Department of Sociology 1126 East 59Th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 219-628-3103 [email protected]

WHITNEY JOHNSON University of Chicago Department of Sociology 1126 East 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 219-628-3103 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Chicago, PhD in Sociology, 2018 Concentrations: Culture, Economy, Theory, Gender, Qualitative Methods Dissertation Title: “Learning to Listen: Knowledge of Value in Auditory Culture” Committee: Karin Knorr Cetina (chair), Andrew Abbott, and Gary Alan Fine University of Chicago, MA in Sociology, 2012 Concentrations: Theory, Culture, Economic, Globalization, Gender Qualifying Paper: “Weird Music and Suggested Donations: Taste Tensions in the Field of Cultural Production” Advisors: Karin Knorr Cetina and John Levi Martin University of Chicago, Harris School of Public Policy, Master of Public Policy, 2009 Concentrations: International Policy, Cultural Policy, Quantitative Methods Honors Paper: “Cultural Policy in Immigrant Communities: A Developmental Dialectic” Readers: Terry Nichols Clark and Alicia Menendez Cedarville University, BA in Theology, 2003 Minors: Psychology, Music, Literature PUBLICATIONS Peer-Reviewed “Weird Music: Tension and Reconciliation in Cultural-Economic Knowledge” Cultural Sociology, March 2017, Volume 11(1): 44-59 Other Publications Book Review for The Work of Art: Value in Creative Careers by Alison Gerber American Sociological Association Sociology of Culture Section Newsletter “Cultural Intermediation: Connecting Communities in the Creative Urban Economy” International Scoping Study, Arts & Humanities Research Council, University of Birmingham, 2013 Principal Investigator: Phil Jones “Cassette Tape Materiality” Shift: Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture, October 2011, Issue 4 “Cultural Policy in Immigrant Communities” Chicago Policy Review, Summer 2010, Volume 14 TEACHING EXPERIENCE University of Chicago Lecturer Self, Culture, and Society, Fall 2017 and Fall 2015 Sociology of the Arts, Spring 2017 (Robert E. -

Gathering of Card Players and Subcultural Expression

THE MAGIC OF COMMUNITY: GATHERING OF CARD PLAYERS AND SUBCULTURAL EXPRESSION Travis J. Limbert A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Dr. Marilyn Motz, Advisor Dr. Esther Clinton © 2012 Travis Limbert All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Marilyn Motz, Advisor When Magic: the Gathering was released in 1993, it was the first trading card game. It paved the way for the trading card game subculture and market that exists today. This thesis explores the implications of this subculture and the ways it can be thought of as an urban leisure subculture. This thesis also discusses Magic’s unique community, which has been instrumental in the game’s success over the last two decades. Magic’s community is created symbiotically, through official support by Wizards of the Coast, and the parent company Hasbro, as well as the usage and interaction by the fans and players. It is this interaction that creates a unique community for Magic, which leads to the game’s global popularity, including its tremendous growth since 2010. This thesis looks at trade publications, articles written about Magic, player responses collected through online surveys, and other works to create an extensive work on Magic and its community. This thesis focuses on how the community is important to the consumption of copyrighted cultural texts and how this creates of meaning in players’ lives. iv To my parents, James and Jona, who always encouraged me. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee, Dr. -

Gary Alan Fine Northwestern University, USA the Meso-World

Gary Alan Fine Northwestern University, U.S.A. The Meso-World: Tiny Publics and Political Action DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.15.2.02 Abstract In recent decades, sociologists have too often ignored the group level—the meso-level of analysis—in their emphasis on either the individual or the institution. This unfortunate absence misses much of what is central to a sociological analysis of community based on “action.” I draw upon Erving Goff- man’s (1983) concept of the interaction order as I argue that a rigorous political sociology requires a focus on group cultures and tiny publics. Group dynamics, idiocultures, and interaction routines are central in creating social order. This approach to civic life draws from the pragmatism of John Dewey, as well as the broad tradition of symbolic interactionist theorists. Ultimately, I argue that a commitment to local action constitutes a commitment to a more extended social system. Keywords Meso-Level of Analysis; Interaction Order; Tiny Publics; Political Order To love the little platoon we belong to in Small Groups and the Political Order society is the first principle…of public affections. It is the first link in the series by How can we explain a revolution, a democratic which we proceed towards a love to our transition, or a conspiracy by shadowy elites? If country, and to mankind. we examine the genesis of the First World War, the Reflections on the French Revolution(1790) French Revolution, the Civil Rights movement, or Edmund Burke the stable governance of a Midwestern farming town in the United States, we find a set of tiny publics (Fine 2012), either working together or Gary Alan Fine is James E. -

Sticky Cultures: Memory Publics and Communal Pasts in Competitive

CUS7410.1177/1749975512473460Cultural SociologyFine 4734602013 Article Cultural Sociology 7(4) 395 –414 Sticky Cultures: Memory © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: Publics and Communal Pasts in sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1749975512473460 Competitive Chess cus.sagepub.com Gary Alan Fine Northwestern University, USA Abstract Although examinations of social memory have largely focused on societies and large populations, much remembrance occurs within bounded publics. This memory, especially when it is held in common, ties individuals to their chosen groups, establishing an ongoing reality of affiliation. I term this form of memory work as sticky culture, recognizing the centrality of the linkage of selves and groups. To examine how sticky culture operates, I examine the social world of competitive chess with its deep history and rich literature. More specifically, I examine forms through which chess publics are cemented through remembrances of the past, focusing on the hero, the critical moment, and validated styles. Champions, memorable games, and recognized strategies establish a lasting public. Keywords chess, collective memory, communal, community, culture, groups, leisure, memory, tiny publics Chess gives not only contemporary fame, but lasting remembrance. To be a great chess player is to be surer of immortality than a great statesman or popular author . The chess player’s fame once gained is secure and stable. What one of all the countless chivalry of Spain is so familiar a name as Ruy Lopez? What American (except Washington) is so widely known as Paul Morphy? Chess, in fact, has lasted so long that we are sure it will last forever. Institutions decay, empires fall to pieces, but the game goes on. -

Curriculum Vitae

Updated: September, 2018 DONILEEN R. LOSEKE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY University of South Florida Tampa, Florida 33620 Office: (813) 974-2517 fax: (813) 974-6455 [email protected] Education: Ph.D. (Sociology) University of California Santa Barbara M.A. (Behavioral Science) California State University B. A. (Psychology) Dominguez Hills Employment: 2012/ Professor of Sociology University of South Florida, Tampa Present 2002/ Professor/Sociology University of South Florida, Tampa 2011 and Graduate Director 1996/ Associate Professor and Chair/ University of South Florida, Tampa 2001 Sociology 1990/ Assistant to Associate Professor/ Skidmore College 1996 Sociology Saratoga Springs, New York 1988/ Visiting Assistant Professor/ Union College 1990 Sociology and Acting Schenectady, New York Director/Women's Studies 1984/ Visiting Assistant Professor/ Skidmore College 1988 Sociology Saratoga Springs, New York Loseke -2- 1982/ Assistant Professor / State University of New York 1983 Sociology Geneseo, New York Awards: 1994: Mentor Award from Sociologists for Women in Society. 1994: Charles Horton Cooley Award for The Battered Woman and Shelters: The Social Construction of Wife Abuse from the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction. 2014: George H. Mead Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction. 2015: Mentor Award from the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction. Publications Books: Narrative Productions of Meaning: Exploring the Work of Stories in Social Life. Lexington Books (forthcoming, 2019) Methodological Thinking: Basic Principles of Social Research Design. Newbury Park: Sage 1st edition: 2013 2nd edition: February 2017 Thinking About Social Problems: An Introduction to Constructionist Perspectives, 2nd edition. NJ: Transaction Books (2003) Reprinted chapter: “How to Successfully Construct a Social Problem.” Pp. -

Towards a Peopled Ethnography: Developing Theory from Group Life Gary Alan Fine Ethnography 2003; 4; 41 DOI: 10.1177/1466138103004001003

Ethnography http://eth.sagepub.com Towards a Peopled Ethnography: Developing Theory from Group Life Gary Alan Fine Ethnography 2003; 4; 41 DOI: 10.1177/1466138103004001003 The online version of this article can be found at: http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/4/1/41 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Ethnography can be found at: Email Alerts: http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://eth.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 9 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/4/1/41 Downloaded from http://eth.sagepub.com at UNIV CALIFORNIA IRVINE on November 26, 2007 © 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. 03 Fine (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:36 am Page 41 ARTICLE graphy Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) www.sagepublications.com Vol 4(1): 41–60[1466–1381(200303)4:1;41–60;031886] Towards a peopled ethnography Developing theory from group life ■ Gary Alan Fine Northwestern University, USA ABSTRACT ■ This article argues for a distinctive form of participant observation which I label peopled ethnography. I contrast this to two alternative ethnographic approaches, the personal ethnography and the postulated ethnography. In a peopled ethnography the text is neither descriptive narrative nor conceptual theory; rather, the understanding of the setting and its theoretical implications are grounded in a set of detailed vignettes, based on field notes, interview extracts, and the texts that group members produce. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Michele\My Documents

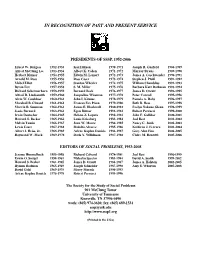

IN RECOGNITION OF PAST AND PRESENT SERVICE PRESIDENTS OF SSSP, 1952-2006 Ernest W. Burgess 1952-1953 Kai Erikson 1970-1971 Joseph R. Gusfield 1988-1989 Alfred McClung Lee 1953-1954 Albert K. Cohen 1971-1972 Murray Straus 1989-1990 Herbert Blumer 1954-1955 Edwin M. Lemert 1972-1973 James A. Geschwender 1990-1991 Arnold M. Rose 1955-1956 Rose Coser 1973-1974 Stephen J. Pfohl 1991-1992 Mabel Elliot 1956-1957 Stanton Wheeler 1974-1975 William Chambliss 1992-1993 Byron Fox 1957-1958 S. M. Miller 1975-1976 Barbara Katz Rothman 1993-1994 Richard Schermerhorn 1958-1959 Bernard Beck 1976-1977 James D. Orcutt 1994-1995 Alfred R. Lindesmith 1959-1960 Jacqueline Wiseman 1977-1978 Peter Conrad 1995-1996 Alvin W. Gouldner 1960-1961 John I. Kitsuse 1978-1979 Pamela A. Roby 1996-1997 Marshall B. Clinard 1961-1962 Frances Fox Piven 1979-1980 Beth B. Hess 1997-1998 Marvin B. Sussman 1962-1963 James E. Blackwell 1980-1981 Evelyn Nakano Glenn 1998-1999 Jessie Bernard 1963-1964 Egon Bittner 1981-1982 Robert Perrucci 1999-2000 Irwin Deutscher 1964-1965 Helena Z. Lopata 1982-1983 John F. Galliher 2000-2001 Howard S. Becker 1965-1966 Louis Kriesberg 1983-1984 Joel Best 2001-2002 Melvin Tumin 1966-1967 Joan W. Moore 1984-1985 Nancy C. Jurik 2002-2003 Lewis Coser 1967-1968 Rodolfo Alvarez 1985-1986 Kathleen J. Ferraro 2003-2004 Albert J. Reiss, Jr. 1968-1969 Arlene Kaplan Daniels 1986-1987 Gary Alan Fine 2004-2005 Raymond W. Mack 1969-1970 Doris Y. Wilkinson 1987-1988 Claire M. Renzetti 2005-2006 EDITORS OF SOCIAL PROBLEMS, 1953-2008 Jerome Himmelhoch 1953-1958 Richard Colvard 1978-1981 Joel Best 1996-1999 Erwin O. -

Gary Alan Fine to Edit Social Psychology Quarterly

VOLUME 34 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2006 NUMBER 7 Gary Alan Fine to Edit Social Psychology Quarterly by Ruth Horowitz and Guillermina (Willie) of Restaurant Work (California 2000) and work. The second is Gary as an academic found them exacting and to the point. Jasso, New York University Moral Tales: The Culture of Mushrooming and his enormous integrity and collegial- Born in New York City, Gary has trav- (Harvard 1998). ity and his strong com- eled across the country in the unfolding Gary Alan Fine, the John Evans Looking over his mitment to the values of of his scholarly life. After Cambridge Professor of Sociology at Northwestern extraordinary 55-page university life. The third, he took his first job at the University University, is an inspired choice for the vita, we were once again as we alluded to above, of Minnesota, then became chair at editorship of Social Psychology Quarterly. suffused with admira- is Gary as connoisseur Georgia before moving to Northwestern Though his appointment is not a sur- tion and delight, as in par excellence of food and University. In between he has visited in prise, some readers may be surprised by all the years we have wine, and especially his Europe, South Africa, and different loca- the varied interests and activities of this known him. One of us youthful annual vigil for tions across this country. This past year creative and prolific sociologist. As the was Gary’s colleague Beaujolais Nouveau. he returned home to New York City as writer of a restaurant blog, Veal Cheeks, he for five years at the Gary took many a Russell Sage Fellow, an appointment describes the birth of his interest in food, University of Minnesota graduate sociology which provided him with ample oppor- “Once long ago in College, I worked where his office was next classes as an undergrad- tunity to research and write his blog. -

Bin Xu Curriculum Vitae Email: [email protected] Personal Website: POSITIONS Associate Professor of Sociology, Emory University

Updated: July 2021 Bin Xu Curriculum Vitae Email: [email protected] Personal Website: www.binxu.net POSITIONS Associate Professor of Sociology, Emory University. 2019- Assistant Professor of Sociology, Emory University. 2016-2019 Postdoctoral Associate, the Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University, 2014-2015 Assistant Professor of Sociology and Asian Studies, Florida International University. 2011-2016 EDUCATION Ph.D., Sociology, Northwestern University. 2011 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS 1. The Politics of Compassion: the Sichuan Earthquake and Civic Engagement in China (2017, Stanford University Press). (http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=26599 ) • The Mary Douglas PriZe for Best Book, Section on the Sociology of Culture, American Sociological Association, 2018 • Best Book on Asia/Transnational, Honorable Mention, Section on Asia and Asian America, American Sociological Association, 2018 • Reviewed in American Journal of Sociology, Choice, Culture Section Newsletter, Journal of Asian Studies, Journal of Chinese Political Science, China Quarterly, China Review International, among others. 2. Chairman Mao’s Children: Generation and the Politics of Memory in China (2021, Cambridge University Press) 3. The Culture of Democracy: A Sociological Approach to Civil Society. Under contract with Polity Press. In “Cultural Sociology” series. SPECIAL ISSUE 1 1. Special Issue. “Catastrophes, Meanings, and Politics in a Global World: Toward a Cultural Sociology of Disasters.” Co-edited with Ming-Cheng Lo (UCDavis). Status: Accepted by Poetics, forthcoming. PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLES 1. Weirong Guo and Bin Xu. Forthcoming. “Dignity in Red Envelopes: Disreputable Exchange and Cultural Reproduction of Inequality in Informal Medical Payment.” Social Psychology Quarterly. Conditional acceptance. 2. Bin Xu and John A. Bernau. 2021. “The Sympathetic Leviathan: Modern States’ Cultural Responses to Disasters.” Poetics. -

KENT L. SANDSTROM Dean and Professor College of Arts

KENT L. SANDSTROM Dean and Professor College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences North Dakota State University NDSU Dept. 2300 Fargo, ND 58108-6050 Tel: (701) 231-8932 EDUCATION 1994 Ph.D. in Sociology, University of Minnesota. 1988 M.A. in Sociology, University of Minnesota. 1977 B.A. in Sociology, Magna Cum Laude, University of Minnesota, Duluth AWARDS 2011 James F. Lubker Award for Faculty Research – Granted by the Office of the Provost and the Awards Committee, University of Northern Iowa, for outstanding research accomplishments. 2005 President’s Special Award – Granted by the Board of Directors of the Midwest Sociological Society for outstanding service and contributions to the Society and profession. 2005 Human Rights Advocacy Award – Granted by Amnesty International, University of Northern Iowa, for outstanding leadership in promoting and defending human rights. 2005 Ross A. Nielsen Professional Service Award – Granted by the Office of the Provost and the Awards Committee, University of Northern Iowa 2005 Distinguished Service Award – Granted by the Faculty Senate of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Northern Iowa 2000 Regents Award for Faculty Excellence – Granted by the Office of the Provost, University of Northern Iowa, for “outstanding contributions across the spectrum of faculty endeavors.” 1999 Outstanding Teaching Award – Granted by the Office of the Provost and the Office of Alumni Relations for Outstanding Teacher of the Year, University of Northern Iowa. 1999 CSBS Outstanding Teaching Award – Granted by the Faculty Senate of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Northern Iowa 1992 Don Martindale Award (co-winner) – Granted for outstanding progress and accomplishments as a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Minnesota.