An In-Depth Study of Camera Phone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Slide Title

December 2007 Updated 12/17/07 AT&T Mobility December ~ Washington Government WSCA – AT&T Mobility Device and Rate Plan Update for 2007 All Offers for Government Use ONLY On the attached pages you will find updates to the December WSCA pricing for Equipment and Rate Plans. Table of Contents Page 2: Voice Rate Plans Page 3: FREE Cellular Phones Page 4: Cellular Phones Page 5: BlackBerry Devices Page 6: SmartPhones (Microsoft, Nokia, Palm) Page 7: Push-to-Talk Devices Page 8: Aircards Page 9: Accessories Page 10: Nationwide Coverage Map December Highlights: ¾New Blackberry 8310 Curve! ~ Onboard GPS ~ Available in Titanium & Red! ¾ New Samsung Blackjack 2 – GPS ~ Available in Black & Red! ¾ Air Card Promotion: Sierra AC881 & Option GT Max FREE! *Certain devices may not be shown due to policy or otherwise WSCA Pricing. For more Information Contact: Prices and Promotions subject to change without notice Rob Holden All Offers for Government Use ONLY 425-580-7741 Master Price Agreement: T07-MST-069 [email protected] All plans receive WSCA 20% discount on monthly recurring service charges December 2007 December 2007 Updated 12/17/07 AT&T Mobility Oregon Government WSCA All plans receive 20% additional discount off of monthly recurring charges! AT&T Mobility Calling Plans REGIONAL Plan NATION Plans (Free Roaming and Long Distance Nationwide) Monthly Fee $9.99 (Rate Code ODNBRDS11) $39.99 $59.99 $79.99 $99.99 $149.99 Included mins 0 450 900 1,350 2,000 4,000 5000 N & W, Unlimited Nights & Weekends, Unlimited Mobile to 1000 Mobile to Mobile Unlim -

Down and Dirty Camera Tricks Even for Your CELL PHONE

Down and Dirty Camera Tricks Even for Your CELL PHONE Educational Seminar GCSAA Presenter - John R. Johnson Creating Images That Count The often quoted Yogi said, “When you come to a Fork in the Road – Take it!” What he meant was . “When you have a Decision in Life – Make it.” Let’s Make Good Decisions with Our Cameras I Communicate With Images You’ve known me for Years. Good Photography Is How You Can Communicate This one is from the Media Moses Pointe – WA Which Is Better? Same Course, 100 yards away – Shot by a Pro Moses Pointe – WA Ten Tricks That Work . On Big Cameras Too. Note image to left is cell phone shot of me shooting in NM See, Even Pros Use Cell Phones So Let’s Get Started. I Have My EYE On YOU Photography Must-Haves Light Exposure Composition This is a Cell Phone Photograph #1 - Spectacular Light = Spectacular Photography Colbert Hills - KS Light from the side or slightly behind. Cell phones require tons of light, so be sure it is BRIGHT. Sunsets can’t hurt either. #2 – Make it Interesting Change your angle, go higher, go lower, look for the unusual. Resist the temptation to just stand and shoot. This is a Cell Phone Photograph Mt. Rainier Coming Home #2 – Make it Interesting Same trip, but I shot it from Space just before the Shuttle re-entry . OK, just kidding, but this is a real shot, on a flight so experiment and expand your vision. This is a Cell Phone Photograph #3 – Get Closer In This Case Lower Too Typically, the lens is wide angle, so things are too small, when you try to enlarge, they get blurry, so get closer to start. -

Visual Mobile Communication Camera Phone Photo Messages As Ritual Communication and Mediated Presence Mikko Villi’S Background Is in Com- Munication Studies

mikko villi Visual mobile communication Camera phone photo messages as ritual communication and mediated presence Mikko Villi’s background is in com- munication studies. He has worked as a researcher at the University of Art and Design Helsinki, University of Tampere and University of Helsin- ki, where he has also held the position of university lecturer. Currently, he works as coordinator of educational operations at Aalto University. Villi has both researched and taught sub- jects related to mobile communica- tion, visual communication, social media, multi-channel publishing and media convergence. Visual mobile communication mikko villi Visual mobile communication Camera phone photo messages as ritual communication and mediated presence Aalto University School of Art and Design Publication series A 103 www.taik.fi/bookshop © Mikko Villi Graphic design: Laura Villi Original cover photo: Ville Karppanen !"#$ 978-952-60-0006-0 !""$ 0782-1832 Cover board: Ensocoat 250, g/m2 Paper: Munken Lynx 1.13, 120 g/m2 Typography: Chronicle Text G1 and Chronicle Text G2 Printed at %" Bookwell Ltd. Finland, Jyväskylä, 2010 Contents acknowledgements 9 1 introduction 13 2 Frame of research 17 2.1 Theoretical framework 19 2.1.1 Ritual communication 19 2.1.2 Mediated presence 21 2.2 Motivation and contribution of the study 24 2.3 Mobile communication as a field of research 27 2.4 Literature on photo messaging 30 2.5 The Arcada study 40 2.6 Outline of the study 45 3 Camera phone photography 49 3.1 The real camera and the spare camera 51 3.2 Networked photography -

Of-Device Finger Gestures

LensGesture: Augmenting Mobile Interactions with Back- of-Device Finger Gestures Xiang Xiao♦, Teng Han§, Jingtao Wang♦ ♦Department of Computer Science §Intelligent Systems Program University of Pittsburgh University of Pittsburgh 210 S Bouquet Street 210 S Bouquet Street Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA {xiangxiao, jingtaow}@cs.pitt.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT becomes the only channel of input for mobile devices, leading to We present LensGesture, a pure software approach for the notorious "fat finger problem" [2, 22], the “occlusion augmenting mobile interactions with back-of-device finger problem” [2, 18], and the "reachability problem" [20]. In gestures. LensGesture detects full and partial occlusion as well as contrast, the more responsive, precise index finger remains idle on the dynamic swiping of fingers on the camera lens by analyzing the back of mobile devices throughout the interactions. Because image sequences captured by the built-in camera in real time. We of this, many compelling techniques for mobile devices, such as report the feasibility and implementation of LensGesture as well multi-touch, became challenging to perform in such a "situational as newly supported interactions. Through offline benchmarking impairment" [14] setting. and a 16-subject user study, we found that 1) LensGesture is easy Many new techniques have been proposed to address these to learn, intuitive to use, and can serve as an effective challenges, from adding new hardware [2, 15, 18, 19] and new supplemental input channel for today's smartphones; 2) input modality, to changing the default behavior of applications LensGesture can be detected reliably in real time; 3) LensGesture for certain tasks [22]. -

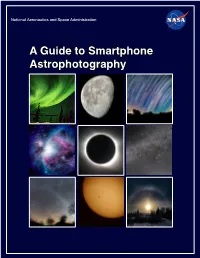

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

Smartwatch Instructions

SMARTWATCH INSTRUCTIONS IOS To download our app, search for RADLEY LONDON WATCH app or scan the appropriate QR code for installation. Use Thank you for purchasing your your smart phone camera or QR code RADLEY LONDON smartwatch reader app. Please follow these instructions The RADLEY LONDON WATCH app will carefully and we’ll soon have you ANDROID work on the following smartphones: up & running with your new watch. Android (version 4.4 and above) Apple IOS (version 8.0 and above) Please ensure the app is the latest version and have Bluetooth 5.0 QUICK START GUIDE CONNECTING BAND TO MOBILE PHONE CHARGING GUIDE 1. Enable Bluetooth on your smartphone. Charging for automatic power-on: 2. Open RADLEY App. on your smart phone, set your profile within settings. 1. Line up the 2 pins to the charging spots on the back of the watch case. 3. Tap connect device within settings. 2. The pins are magnetic and will secure the charger in place. 4. Select Smart Bracelet as shown. 3. Plug in the USB cable to a power source. Once connected, a charging icon 5. Follow the steps, search for RADLEY LONDON device will appear on screen. name and connect. 4. Please charge the band when it displays low battery. 6. Within the notifications section, select the 5. A 2 hour charge time is sufficient to fully charge your smartwatch. Please notification types you want your band to receive. ensure you do not exceed a 2 hour charge period. OPERATION INTRODUCTION DISCONNECTING YOUR SMART WATCH & PHONE • To switch on the watch, press and hold the side button until the display is on. -

Optical Design of the 13 Mega-Pixels Mobile Phone Camera Pengbo Chen

3rd International Conference on Materials Engineering, Manufacturing Technology and Control (ICMEMTC 2016) Optical design of the 13 mega-pixels mobile phone camera Pengbo Chen,Xingyu Gaoa,* Institute of Intelligent Opto-mechatronics and Advanced Manufacture Technology, College of Electromechanical Engineering, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin 541004,China. a,*[email protected] Corresponding Author:Xingyu Gao Keywords: Optical design ; Mobile phone lens; Aspherical surface; Abstract. According to the market demand for high resolution cell phone camera,a 13 mega-pixels camera lens applying aspherical surfaces is designed using the ZEMAX optical design software. The lens is consisted by four pieces of aspherical plastic lens, an optical filter and a piece of protection glass. The lens has the optical performance of F-number 2.8, viewing angle 76°, focal length 4.4 mm, back focal length 0.58 mm, and total length 5.6 mm. After the tolerance analyzing, its tolerance meets the processing requirements, which can satisfy the requirements of the commercial sell phone. 1. Introduction Since 2000, Japan's Sharp Co launched the world's first camera phone. Camera function has become an essential feature of the phone. In 2003, Sony launched the first mobile phone with camera function, model for Ericsson T618, this phone installed 10 million pixel mobile phone lens, which is the earliest a camera phone, marking China's entry into the era of mobile phone camera on the Chinese market. In 2006, Zhu Rihong [1], who designed a f / 3.2, field of view angle of 55 degrees, pixel reached 160 million of the lens, the lens system as the total length of 5mm.In 2008, Liu Maochao [2], who designed a F/2.85, field of view angle of 62 degrees, pixel to 3 million of the lens, the system length of the lens is 5.26mm.In 2009, Li Wenjing [3], who designed a F/2.8, the field of view angle of 65 degrees, pixel 5 million of the mobile phone lens, the total length of the lens system is 5.8mm. -

Samsung Galaxy Camera Forensics

Combining technical and legal expertise to deliver investigative, discovery and forensic solutions worldwide. SAMSUNG GALAXY April 11, 2013 Introduction. The Samsung Galaxy camera was Operating System: Abstract released on November 16, 2012. This Android 4.1 (Jellybean) Samsung Galaxy Camera device has the potential to replace mobile Network:2G, 3G or 4G (LTE) phones, as it has the same functionality GSM, HSPA+ Forensics of a smartphone, with the additional perk of a high quality camera. This creates an Processor:1.4 GHz Quad Core attractive incentive to buy the camera, Memory:microSD, 4GB on The purpose of this project which could lead to the possibility of it board, 1GB RAM was to determine whether or not forensics on the Samsung Galaxy becoming more popular. Connectivity: WiFI As the camera’s popularity rises in the 802.11a/b/g/n, WiFi hotspot camera was possible. Although market, and more users purchase the the camera runs an Android device, the risk of the camera being used Bluetooth:Yes operating system, there was still a chance that no data could be in an illicit manner rises as well. As the GPS:Yes extracted, as forensics on this Samsung Galaxy camera is now a part device had never been done of an investigator’s scope, understanding Table 1. before. To begin the process of where any evidence can be retrieved Goals. this project, as much data as is crucial. Using several different The goal for this project was to possible had to be created on forensic tools, any data that could be of develop an informational guide for the the camera by utilizing all of the applications and features that evidentiary value is detailed in this paper. -

Sony Ericsson C905a 8.1 Megapixel Cyber-Shot™ Camera Phone

Sony Ericsson C905a 8.1 Megapixel Cyber-shot™ Camera Phone The Sony Ericsson phone designed for the photographer in you. Picture this: A Sony Ericsson phone that’s also an 8.1 megapixel Cyber-shot™ camera. With the C905a, it’s a snap to create brilliant images with user-friendly features such as auto-focus, face detection, and xenon flash with red-eye reduction. Smart Contrast helps to brighten underexposed subjects. BestPic™ captures subjects that just won’t sit still. Scene options provide a simple method to set camera settings automatically for getting 8.1 Megapixel Cyber-shot™ Camera the best exposure out of a particular situation. GPS with AT&T Navigator The C905a is ready when you are to capture the moments you won’t want to miss. All this in a AT&T Video Share stylish 3G phone that offers all the high quality AT&T Mobile Music services and performance you expect from AT&T. Email and Messaging For more information, visit att.com/wireless or call 866-MOBILITY. Screen images are simulated or enhanced. The Liquid Identity logo is a trademark or registered trademark of Sony Ericsson Mobile Communications AB. Sony and Cyber-shot are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sony Corporation. Ericsson is a trademark or registered trademark of Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson. Yahoo! is a trademark or a registered trademark of Yahoo! Inc. Apple is a trademark or a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Facebook is a trademark or a registered trademark of Facebook, Inc. Wal-Mart is a trademark or registered trademark of Wal-Mart Stores Inc. -

Autofocus Measurement for Imaging Devices

Autofocus measurement for imaging devices Pierre Robisson, Jean-Benoit Jourdain, Wolf Hauser Clement´ Viard, Fred´ eric´ Guichard DxO Labs, 3 rue Nationale 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt FRANCE Abstract els of the captured image increases with correct focus [3], [2]. We propose an objective measurement protocol to evaluate One image at a single focus position is not sufficient for focus- the autofocus performance of a digital still camera. As most pic- ing with this technology. Instead, multiple images from differ- tures today are taken with smartphones, we have designed the first ent focus positions must be compared, adjusting the focus until implementation of this protocol for devices with touchscreen trig- the maximum contrast is detected [4], [5]. This technology has ger. The lab evaluation must match with the users’ real-world ex- three major inconveniences. First, the camera never can be sure perience. Users expect to have an autofocus that is both accurate whether it is in focus or not. To confirm that the focus is correct, and fast, so that every picture from their smartphone is sharp and it has to move the lens out of the right position and back. Sec- captured precisely when they press the shutter button. There is ond, the system does not know whether it should move the lens a strong need for an objective measurement to help users choose closer to or farther away from the sensor. It has to start moving the best device for their usage and to help camera manufacturers the lens, observe how contrast changes, and possibly switch di- quantify their performance and benchmark different technologies. -

Digital Cameras and Expanding Mobile Handset Functions: Competing Value Chains in the Consumer Imaging Industry

Digital Cameras and Expanding Mobile Handset Functions: Competing Value Chains in the Consumer Imaging Industry Yuri Park, Seoul National University, Techno-Economics and Policy Program, Seoul, South Korea Milton Mueller, Syracuse University, School of Information Studies, Syracuse, New York We selected six attributes for purchasing devices. (See Table Abstract 1) The alternatives that we considered in this study are confined to This paper explores the competition between specialized, digital cameras and camera phones in order to isolate the stand-alone digital cameras and digital cameras that are bundled relationship between them. with mobile telephones. It uses conjoint survey research to Our conjoint survey of capture devices relied on six attributes. determine whether camera phones and digital cameras are The first attribute was resolution; i.e., the quality of the pictures complements or substitutes, and to find out how much consumer taken by the device. The resolution of most camera phones is lower value specific features of cameras, such as LCD screen size, an than the norm for digital cameras, but can be expected to increase.1 internet connection, zoom, and so on. But no one knows the extent to which consumers want higher resolution. If consumers are satisfied with moderate resolution Introduction levels, there will be no reason to concentrate on developing camera Handheld phones now can provide digital cameras, PDAs, phones with significantly higher resolution. The second attribute of storage and playback of images, video and music. The convergence a capture device is the zoom function. This includes both optical of mobile handsets with digital imaging capabilities in particular has and digital zoom. -

DXOMARK Objective Video Quality Measurements

https://doi.org/10.2352/ISSN.2470-1173.2020.9.IQSP-166 © 2020, Society for Imaging Science and Technology DXOMARK Objective Video Quality Measurements Emilie Baudin1, Franc¸ois-Xavier Bucher2, Laurent Chanas1 and Fred´ eric´ Guichard1 1: DXOMARK, Boulogne-Billancourt, France 2: Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA Abstract thus they cannot be considered comprehensive video quality mea- Video capture is becoming more and more widespread. The surement protocols. Temporal aspects of video quality begin to be technical advances of consumer devices have led to improved studied; for instance, a perceptual study of auto-exposure adapta- video quality and to a variety of new use cases presented by so- tion has been presented by Oh et al. [8]. To the best of our knowl- cial media and artificial intelligence applications. Device man- edge, there is not as yet a measurement protocol with correlation ufacturers and users alike need to be able to compare different to subjective perception for video image quality. cameras. These devices may be smartphones, automotive com- The goal of this work is to provide a measurement protocol ponents, surveillance equipment, DSLRs, drones, action cameras, for the objective evaluation of video quality that reliably allows to etc. While quality standards and measurement protocols exist for compare different cameras. It should allow to automatically rank still images, there is still a need of measurement protocols for cameras in the same order a final user would do it. In this article, video quality. These need to include parts that are non-trivially we focus on three temporal metrics: exposure convergence, color adapted from photo protocols, particularly concerning the tem- convergence, and temporal visual noise.