How Should Inheritance Law Remediate Inequality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010 Contract negotiations, management and meeting arrangements for ASSA meetings are conducted by the American Economic Association. i ASSA_Program.indb 1 11/17/09 7:45 AM Thanks to the 2010 American Economic Association Program Committee Members Robert Hall, Chair Pol Antras Ravi Bansal Christian Broda Charles Calomiris David Card Raj Chetty Jonathan Eaton Jonathan Gruber Eric Hanushek Samuel Kortum Marc Melitz Dale Mortensen Aviv Nevo Valerie Ramey Dani Rodrik David Scharfstein Suzanne Scotchmer Fiona Scott-Morton Christopher Udry Kenneth West Cover Art is by Tracey Ashenfelter, daughter of Orley Ashenfelter, Princeton University, former editor of the American Economic Review and President-elect of the AEA for 2010. ii ASSA_Program.indb 2 11/17/09 7:45 AM Contents General Information . .iv Hotels and Meeting Rooms ......................... ix Listing of Advertisers and Exhibitors ................xxiv Allied Social Science Associations ................. xxvi Summary of Sessions by Organization .............. xxix Daily Program of Events ............................ 1 Program of Sessions Saturday, January 2 ......................... 25 Sunday, January 3 .......................... 26 Monday, January 4 . 122 Tuesday, January 5 . 227 Subject Area Index . 293 Index of Participants . 296 iii ASSA_Program.indb 3 11/17/09 7:45 AM General Information PROGRAM SCHEDULES A listing of sessions where papers will be presented and another covering activities such as business meetings and receptions are provided in this program. Admittance is limited to those wearing badges. Each listing is arranged chronologically by date and time of the activity; the hotel and room location for each session and function are indicated. CONVENTION FACILITIES Eighteen hotels are being used for all housing. -

TIWARI-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Bhavya Tiwari 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Bhavya Tiwari Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South Committee: Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Supervisor David Damrosch Martha Ann Selby Cesar Salgado Hannah Wojciehowski Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South by Bhavya Tiwari, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication ~ For my mother ~ Acknowledgements Nothing is ever accomplished alone. This project would not have been possible without the organic support of my committee. I am specifically thankful to my supervisor, Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, for giving me the freedom to explore ideas at my own pace, and for reminding me to pause when my thoughts would become restless. A pause is as important as movement in the journey of a thought. I am thankful to Martha Ann Selby for suggesting me to subhead sections in the dissertation. What a world of difference subheadings make! I am grateful for all the conversations I had with Cesar Salgado in our classes on Transcolonial Joyce, Literary Theory, and beyond. I am also very thankful to Michael Johnson and Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski for patiently listening to me in Boston and Austin over luncheons and dinners respectively. I am forever indebted to David Damrosch for continuing to read all my drafts since February 2007. I am very glad that our paths crossed in Kali’s Kolkata. -

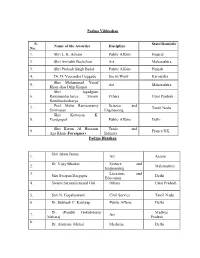

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

![Vf/Klwpukwww Ubz Fnyyh] 8 Vizsy] 2015 Laaaa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2764/vf-klwpukwww-ubz-fnyyh-8-vizsy-2015-laaaa-822764.webp)

Vf/Klwpukwww Ubz Fnyyh] 8 Vizsy] 2015 Laaaa

jftLVªh laö Mhö ,yö&33004@99 REGD. NO. D. L.-33004/99 vlk/kj.k EXTRAORDINARY Hkkx I—[k.M 1 PART I—Section 1 izkf/dkj ls izdkf'kr PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY la- 83] ubZ fnYyh] cq/okj] vçSy 8] 2015@pS=k 18] 1937 No. 83] NEW DELHI, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 8, 2015/CHAITRA 18, 1937 jk”Vªifr lfpoky; vf/vf/vf/kvf/ kkklwpuklwpuk ubZ fnYyh] 8 vizSy] 2015 lalala-la--- 35&izst@201535&izst@2015----&&&&Hkkjr ds jk”Vªifr fuEufyf[kr in~e iqjLdkj lg”kZ iznku djrs gSa %& in~e foHkw”k.k 1- Jh vferkHk cPpu] dyk] egkjk”Vª A 2- Jh /keZLFky ohjsUnz gsXxMs] lekt lsok] dukZVd A 3- egkefge ‘kgtknk djhe vkxk [kku] lekt lsok] Ýkal A 4- Jh eksgEen ;qlwQ [kku mQZ fnyhi dqekj] dyk] egkjk”Vª A 5- izks- ewywj jkeLokfe Jhfuoklu] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] rfeyukMq A 6- Jh ds- ds- os.kqxksiky] yksddk;Z] fnYyh A in~e Hkw”k.k 1- Jh tkg~uw c#vk] dyk] vle A 2- izks- e×ktqy HkkxZo] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] ;q-,l-,- A 3- MkW- fot; HkVdj] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] egkjk”Vª A 4- Lokeh lR;fe=kuUn fxfj] vk/;kfRed f’k{kk] mRrjk[kaM A 5- MkW- lqHkk”k dk’;i] yksddk;Z] fnYyh A 6- MkW- if.Mr xksdqyksRloth egkjkt] dyk] e/; izns’k A 1599 GI/2015 (1) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [P ART I—SEC . 1] 7- MkW- vEcjh’k feRFky] fpfdRlk] fnYyh A 8- Jh f’kodqekj Lokfexyq] vk/;kfRed f’k{kk] dukZVd A in~e Jh 1- Jhefr lck vatqe] [ksy] NRrhlx<+ A 2- Jh ,l- v:.ku] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] dukZVd A 3- MkW- csRrhuk ‘kkjnk ckSej] lkfgR; ,oa f’k{kk] fgekpy izns’k A 4- Jh v’kksd Hkxr] lekt lsok] >kj[kaM A 5- izks- tWd Cykeksa] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] Ýkal A 6- izks- ¼MkW-½ y{eh uUnu cjk] lkfgR; ,oa f’k{kk] vle A 7- MkW- ;ksxs’k -

An Agency Theory of Dividend Taxation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES AN AGENCY THEORY OF DIVIDEND TAXATION Raj Chetty Emmanuel Saez Working Paper 13538 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13538 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2007 We thank Alan Auerbach, Martin Feldstein, Roger Gordon, Kevin Hassett, James Poterba, and numerous seminar participants for very helpful comments. Joseph Rosenberg and Ity Shurtz provided outstanding research assistance. Financial support from National Science Foundation grants SES-0134946 and SES-0452605 is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Raj Chetty and Emmanuel Saez. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. An Agency Theory of Dividend Taxation Raj Chetty and Emmanuel Saez NBER Working Paper No. 13538 October 2007 JEL No. G3,H20 ABSTRACT Recent empirical studies of dividend taxation have found that: (1) dividend tax cuts cause large, immediate increases in dividend payouts, and (2) the increases are driven by firms with high levels of shareownership among top executives or the board of directors. These findings are inconsistent with existing "old view" and "new view" theories of dividend taxation. We propose a simple alternative theory of dividend taxation in which managers and shareholders have conflicting interests, and show that it can explain the evidence. Using this agency model, we develop an empirically implementable formula for the efficiency cost of dividend taxation. -

The Poverty Puzzle

THE POVERTY PUZZLE TIMESFREEPRESS.COM / POVERTYPUZZLE PUBLISHED MARCH 6, 2016 EDITOR’S NOTE n 2015, the Chatta- hood that has seen better times. And we see nooga Times Free panhandlers with cardboard signs standing Press poured an un- at intersections seeking a handout. But we precedented amount quickly forget, lost in our own lives. of time and energy Truth is, poverty usually doesn’t directly I into researching affect most of us unless someone we know the roots of and (maybe us) is laid off and finds it hard to solutions to Chat- land another job. Or perhaps someone in tanooga’s economic our family is hard hit by medical expenses reality; we made this investment as other re- and faces not having enough money, too gional news outlets were pulling back from many bills and a genuine fear of losing our long-term reporting projects. home. Suddenly, poverty becomes very real. Initially, the idea behind The Poverty In our reporting, we discovered that our Puzzle series was fairly cliché: the tale of region, state and city are being crippled by two cities. Chattanooga had been getting powerful forces that aren’t being discussed a significant amount of positive attention publicly. Chattanooga can certainly boast nationally, but on the ground, our reporters about its good numbers: lower unemploy- saw another story unfolding. ment, job growth in high-paying fields, low After the Great Recession, poverty in- taxes and relatively low cost of living. But creased among all ethnic groups in the city, its there are other numbers and cutting-edge outlying suburbs, the rural pockets of Hamil- research being ignored that will matter greatly ton County and the greater metro area. -

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Important Awards and Honours Winner Prize Awarded By/Theme/Purpose Hyderabad International CII - GBC 'National Energy Carbon Neutral Airport having Level Airport Leader' and 'Excellent Energy 3 + "Neutrality" Accreditation from Efficient Unit' award Airports Council International Roohi Sultana National Teachers Award ‘Play way method’ to teach her 2020 students Air Force Sports Control Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Air Marshal MSG Menon received Board Puruskar 2020 the award NTPC Vallur from Tamil Nadu AIMA Chanakya (Business Simulation Game)National Management Games(NMG)2020 IIT Madras-incubated Agnikul TiE50 award Cosmos Manmohan Singh Indira Gandhi Peace Prize On British broadcaster David Attenborough Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Best Screenplay award at Earlier, it was honoured with the Disciple Venice International Film International Critics’ Prize awarded Festival by FIPRESCI. Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland Golden Lion award at Venice International Film Festival Aditya Puri (MD, HDFC Bank) Lifetime Achievement Award Euromoney Awards of Excellence 2020. Margaret Atwood (Canadian Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s writer) lifetime achievement award 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB PO Mains 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB Clerk Mains 2020 Follow us: Telegram , Facebook , Twitter , Instagram 1 Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Rome's Fiumicino Airport First airport in the world to Skytrax (Leonardo -

GK Digest 2015 This Was Part of PM Modi’S Visit to Three Indian Ocean Island Countries

www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com GKBy Ramandeep Singh Digest 2015 my pc [Pick the date] www.BankExamsToday.com GK DigestIndex 2015 List of Prime Minister’s Foreign visits 2-5 MoUs signed between India and Korea 5-14 List of Countries - Their Capital, Currency and Official Language 14-20 Popular Governmentwww.BankExamsToday.com Welfare Schemes 20-21 Awards and Honours in India – 2014 22 Awards and Honours in India 2015 23-30 Appointments 30-40 List of Committees in India 2015 40 International Summits in 2015 List 41-43 People in News During August 2015 43-45 Deaths 45-51 International Military Training Exercises 51-52 List of Cabinet Minister as on 30.11.2014 53-54 Union Budget 2015-16 54-58 Ministers and their constituencies 58-59 Important Indian Organizations and their Heads 59-60 Mergers and Acquisitions - Explained in Simple Language 60-62 List of Latest schemes and apps launched by banks 2015 63 Important Parliamentary Acts related to Banking sector in India 63-65 List of important days for banking and insurance exams 65-66 List of important days, useful for general awareness Section of banking exams 66-68 Important days to remember for August, September and October 68-69 Indian States - Capital - Chief Minister (CM) - Governor 69-72 List of important International Organizations with their headquarters, foundation years, heads and purpose 72-75 Wilf Life Sanctuaries in India 75-81 Indian Cities on the Bank of Important Rivers 82-83 List of national parks of India 83-88 Important Airports 89 IMPORTANT TEMPLES OF INDIA 90-97 LIST OF IMPORTANT CUPS AND TROPHIES – SPORTS 98-99 UNESCO HERITAGE SITES 99-127 Must Know Articles of Indian Constitution 128-132 Important Fairs 133-134 World Major Space Centers 134 www.BankExamsToday.com Page 2 www.BankExamsToday.com List of PrimeGK Minister’sDigest 2015 Foreign visits State Visit to Bhutan (June 15-16, 2014): At the invitation of Shri Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the King of Bhutan, Shri Narendra Modi paid a State Visit to Bhutan from 15-16 June 2014. -

Elsa Dorfman, Portraitist

Criminal Injustice • Presidential Transition • Microbial Earth SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2017 • $4.95 Elsa Dorfman, Portraitist Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2017, VOLUME 120, NUMBER 1 FEATURES 30 The Portraitist | by Sophia Nguyen Elsa Dorfman’s Polaroid photographs captured generations, uniquely 38 Vita: Carl Thorne-Thomsen | by Bonnie Docherty Brief life of a man of principle: 1946-1967 p. 14 40 Life Beyond Sight | by Jonathan Shaw Tiny organisms loom large in shaping Planet Earth 44 Criminal Injustice | by Michael Zuckerman Alec Karakatsanis v. “money-based detention” in America JOHN HARVARD’S JOURNAL 14 President Faust sets her departure, campus building booms, making a MOOC at HarvardX, around and across the Bay of Bengal, proposed final-club finis, back-to-school bookshelf, crossing the Channel the hard way, a business-engineer- ing matchup, new Press director, College p. 25 friendship, new Undergraduate Fellows, and field p. 40 hockey’s finely tuned coach DEPARTMENTS 2 Cambridge 02138 | Letters from our readers—and a comment on presidential-search priorities 3 The View from Mass Hall , CAKEBOX PRODUCTIONS LLC; REBECCA CLARKE 6 Right Now | Enhanced amputation, analyzing anti-aging agents, why cities thrive 12A Harvard2 | Autumn events, river views of Boston, a Shaker village’s enduring appeal, World’s End, Watertown bistro LIFE THE AT EDGE OF SIGHT: A PHOTOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION OF THE THE JUSTICE PROJECT JUSTICE THE 53 Montage | Perfecting the pop song, leadership, American bards, Malka Older’s sci-fi thrillers, seeing the color in art, Adam and Eve, and more 63 Alumni | Precise bird painter, new alumni president 68 The College Pump | Crimson satire, memorial-minute meanings, Memorial Hall aflame p. -

The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children

The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment∗ Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz Harvard University and NBER August 2015 Abstract The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment offered randomly selected families living in high- poverty housing projects housing vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. We present new evidence on the impacts of MTO on children's long-term outcomes using administrative data from tax returns. We find that moving to a lower-poverty neighborhood significantly improves college attendance rates and earnings for children who were young (below age 13) when their families moved. These children also live in better neighborhoods themselves as adults and are less likely to become single parents. The treatment effects are substantial: children whose families take up an experimental voucher to move to a lower-poverty area when they are less than 13 years old have an annual income that is $3,477 (31%) higher on average relative to a mean of $11,270 in the control group in their mid-twenties. In contrast, the same moves have, if anything, negative long-term impacts on children who are more than 13 years old when their families move, perhaps because of the disruption effects of moving to a very different environment. The gains from moving fall with the age when children move, consistent with recent evidence that the duration of exposure to a better environment during childhood is a key determinant of an individual's long-term outcomes. The findings imply that offering vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods to families with young children who are living in high- poverty housing projects may reduce the intergenerational persistence of poverty and ultimately generate positive returns for taxpayers. -

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore Bharat Ratna Award: List of recipients Year Laureates Brief Description 1954 C. Rajagopalachari An Indian independence activist, statesman, and lawyer, Rajagopalachari was the only Indian and last Governor-General of independent India. He was Chief Minister of Madras Presidency (1937–39) and Madras State (1952–54); and founder of Indian political party Swatantra Party. Sarvepalli He served as India's first Vice- Radhakrishnan President (1952–62) and second President (1962–67). Since 1962, his birthday on 5 September is observed as "Teachers' Day" in India. C. V. Raman Widely known for his work on the scattering of light and the discovery of the effect, better known as "Raman scattering", Raman mainly worked in the field of atomic physics and electromagnetism and was presented Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930. 1955 Bhagwan Das Independence activist, philosopher, and educationist, and co-founder of Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapithand worked with Madan Mohan Malaviya for the foundation of Banaras Hindu University. M. Visvesvaraya Civil engineer, statesman, and Diwan of Mysore (1912–18), was a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. His birthday, 15 September, is observed as "Engineer's Day" in India. Jawaharlal Nehru Independence activist and author, Nehru is the first and the longest-serving Prime Minister of India (1947–64). 1957 Govind Ballabh Pant Independence activist Pant was premier of United Provinces (1937–39, 1946–50) and first Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh (1950– 54). He served as Union Home Minister from 1955–61. 1958 Dhondo Keshav Karve Social reformer and educator, Karve is widely known for his works related to woman education and remarriage of Hindu widows. -

Notice for Writtten EXAM (List of Provisonlly Eligible Candidates)

Notice of Written Examination The Written Exam for the following Posts will be conducted on 02.11.2008 (Sunday) in two shifts. The details are as under:- S.No. Name of the Post Shift Timings 1 Manager (Electrical /Cargo/ Commercial Morning Shift 10.00 AM Jr.Executive (P&A/ Arch.) 2 Manager (Airport Operation/Fire Service) Evening Shift 02.30 PM Jr.Executive (IT/Eqpt.) Admit cards have been dispatched to the provisionally eligible candidates individually. In case of non-receipt of Admit Card, duplicate Admit Card can be had in person from this office from 22nd October,08 except Saturday/Sunday and Gagetted holiday. Candidates who did not come here in person are advised to go directly to the examination centre (As per Centre for written exam adopted in the application form) and request to Nodal Officer, AAI at the Venue on the Schedule date of exam. It may be noted that duplicate Admit Card will be issued only those candidates whose name are exist in our master list of provisionally eligible candidates. Candidates are also advised to bring one passport size photo, identical to the photo pasted on their application forms for further enquires, candidates can contact over telephone No. 011-24632950 Extn.2431/2449/2467 from 9.30 AM to 5.30PM.on all working days. The names of the examination centre are as under:- S.No. Centre Venue for Morning Shift- Venue for Evening Shift- For Manager (Electrical For Manager (Airport /Cargo /Commercial) and Operation/Fire Service) JE (P&A/Arch) and JE (IT/Equpt) Kendriya Vidalaya No.1, 1.