An Annotated Che Klist of the Fishes of Clipperton Atoll, Tropical Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

Abstract for Submission to the 11Th International Coral Reef

Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations in Aceh, Sumatra: Local Knowledge of Occurrence and Status Authors: Campbell S.J., Mukmunin, A., Prasetia, R The Wildlife Conservation Society, Indonesian Marine Program, Jalan Pangrango 8, Bogor 16141, Indonesia Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations (FSA) are critical in the life cycle of the fishes that use this reproductive strategy as sources of larvae, but are also highly vulnerable to over exploitation. With the exception of the Komodo (Pet et al. 2005) little if any research has been focused on FSAs in Indonesia. Interview surveys were conducted among fishing communities on the island of Weh in northern Aceh in order to determine the level of awareness of FSAs among fishers; which reef fish species form FSAs; sites of aggregation formation; seasonal patterns; and to assess fishing pressure on and status of FSAs. Results show that many fishers possess reliable knowledge of spawning areas, species and times. Possible FSAs were reported from a number of areas on Weh island inside and outside protected areas. Of the 47 species of fish mentioned by respondents, we conclude that six species are very likely to form spawning aggregations in marine waters of Weh island. All six species were mentioned by more than 10 fishers, and included Bolbometopoton muricatum (Scaridae: Bumpheaded parrotfish), Cepahpholis miniata (Serranidae: Coral grouper) Variola louti (Serranidae: Yellow Edged Lyretail), Cheilinus undulatas (Labridae: Napolean wrasse), Thunnus albacares (Yellow fin tuna) and Caranx lugubris (Carangidae: Black Jack Trevally). FSAs in Aceh were areas targeted by fishers, although many were inside existing marine protected areas where prohibitions on netting from boats are in place. -

Caranx Lugubris (Black Jack)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Caranx lugubris (Black Jack) Family: Carangidae (Jacks and Pompanos) Order: Perciformes (Perch and Allied Fish) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fish) Fig. 1. Black jack, Caranx lugubris. [http://marinebio.org/upload/Caranx-lugubris/1.jpg, downloaded 14 February 2016] TRAITS. Being built for speed, Caranx lugubris have a steep sloping head with a body that tapers down to a very narrow tail (Lin and Shao, 1999). The colour of the body and head are almost uniformly greyish-brown to black, they have a deeply forked tail (Fig. 1), and the average body length is around 70cm (Humann, 1989). The teeth of the upper jaw include strong canines, and there are about 8 upper and 18-21 lower gill-rakers on the gill arches. DISTRIBUTION. Caranx lugubris is widely distributed in tropical waters worldwide (Fig. 2), with a circumtropical distribution (Smith-Vaniz, 1986). This includes the waters of the Indian Ocean, Pacific, the Atlantic including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean (Smith-Vaniz et al., 2015). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. This species of fish lives in offshore waters at depths of 10-350m (Lieske and Myers, 1994). This species is a bentho-pelagic marine fish that dwells in coral reefs, at the edges of reefs and rocks (Carpenter, 2002). They tend to form schools and primarily feed on other fish (Smith-Vaniz et al., 2015). They tend to live in solitude or in schools consisting of up to 30 individuals (Fig. -

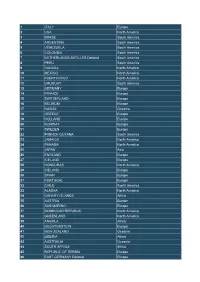

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

Morphological and Karyotypic Differentiation in Caranx Lugubris (Perciformes: Carangidae) in the St. Peter and St. Paul Archipelago, Mid-Atlantic Ridge

Helgol Mar Res (2014) 68:17–25 DOI 10.1007/s10152-013-0365-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Morphological and karyotypic differentiation in Caranx lugubris (Perciformes: Carangidae) in the St. Peter and St. Paul Archipelago, mid-Atlantic Ridge Uedson Pereira Jacobina • Pablo Ariel Martinez • Marcelo de Bello Cioffi • Jose´ Garcia Jr. • Luiz Antonio Carlos Bertollo • Wagner Franco Molina Received: 21 December 2012 / Revised: 16 June 2013 / Accepted: 5 July 2013 / Published online: 24 July 2013 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg and AWI 2013 Abstract Isolated oceanic islands constitute interesting Introduction model systems for the study of colonization processes, as several climatic and oceanographic phenomena have played Ichthyofauna on the St. Peter and St. Paul Archipelago an important role in the history of the marine ichthyofauna. (SPSPA) is of great biological interest, due to its degree The present study describes the presence of two morpho- of geographic isolation. The region is a remote point, far types of Caranx lugubris, in the St. Peter and St. Paul from the South American (&1,100 km) and African Archipelago located in the mid-Atlantic. Morphotypes were (&1,824 km) continents, with a high level of endemic fish compared in regard to their morphological and cytogenetic species (Edwards and Lubbock 1983). This small archi- patterns, using C-banding, Ag-NORs, staining with CMA3/ pelago is made up of four larger islands (Belmonte, St. DAPI fluorochromes and chromosome mapping by dual- Paul, St. Peter and Bara˜o de Teffe´), in addition to 11 color FISH analysis with 5S rDNA and 18S rDNA probes. smaller rocky points. The combined action of the South We found differences in chromosome patterns and marked Equatorial Current and Pacific Equatorial Undercurrent divergence in body patterns which suggest that different provides a highly complex hydrological pattern that sig- populations of the Atlantic or other provinces can be found nificantly influences the insular ecosystem (Becker 2001). -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Snake Eels (Ophichthidae) of the Remote St. Peter and St. Paul's Archipelago (Equatorial Atlantic): Museum Records After 37 Ye

Arquipelago - Life and Marine Sciences ISSN: 0873-4704 Snake eels (Ophichthidae) of the remote St. Peter and St. Paul’s Archipelago (Equatorial Atlantic): Museum records after 37 years of shelf life OSMAR J. LUIZ AND JOHN E. MCCOSKER Luiz, O.J. and J.E. McCosker 2018. Snake eels (Ophichthidae) of the remote St. Peter and St. Paul’s Archipelago (Equatorial Atlantic): Museum records after 37 years of shelf life. Arquipelago. Life and Marine Sciences 36: 9 - 13. Despite of its major zoogeographical interest, the biological diversity of central Atlantic oceanic islands are still poorly known because of its remoteness. Incomplete species inventories are a hindrance to macroecology and conservation because knowledge on species distribution are important for identifying patterns and processes in biodiversity and for conservation planning. Records of the snake-eel family Ophichthidae for the St. Peter and St. Paul’s Archipelago, Brazil, are presented for the first time after revision of material collected and deposited in a museum collection 37 yrs ago. Specimens of Apterichtus kendalli and Herpetoichthys regius were collected using rotenone on sand bottoms and one Myrichthys sp. was observed and photographed swimming over a rocky reef. Remarkably, these species were not seen or collected in the St. Peter and St. Paul’s Archipelago ever since despite the substantial increase of biological expeditions over the past two decades, suggesting that the unjustified rotenone sampling prohibition in Brazil is hindering advancement of the nation’s biological diversity knowledge. Key words: Central Atlantic islands, Anguilliformes, sampling bias, rotenone prohibition. Osmar J. Luiz (e-mail: [email protected]), Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0810 Australia. -

The Global Trade in Marine Ornamental Species

From Ocean to Aquarium The global trade in marine ornamental species Colette Wabnitz, Michelle Taylor, Edmund Green and Tries Razak From Ocean to Aquarium The global trade in marine ornamental species Colette Wabnitz, Michelle Taylor, Edmund Green and Tries Razak ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNEP World Conservation This report would not have been The authors would like to thank Helen Monitoring Centre possible without the participation of Corrigan for her help with the analyses 219 Huntingdon Road many colleagues from the Marine of CITES data, and Sarah Ferriss for Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK Aquarium Council, particularly assisting in assembling information Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 Aquilino A. Alvarez, Paul Holthus and and analysing Annex D and GMAD data Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 Peter Scott, and all trading companies on Hippocampus spp. We are grateful E-mail: [email protected] who made data available to us for to Neville Ash for reviewing and editing Website: www.unep-wcmc.org inclusion into GMAD. The kind earlier versions of the manuscript. Director: Mark Collins assistance of Akbar, John Brandt, Thanks also for additional John Caldwell, Lucy Conway, Emily comments to Katharina Fabricius, THE UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION Corcoran, Keith Davenport, John Daphné Fautin, Bert Hoeksema, Caroline MONITORING CENTRE is the biodiversity Dawes, MM Faugère et Gavand, Cédric Raymakers and Charles Veron; for assessment and policy implemen- Genevois, Thomas Jung, Peter Karn, providing reprints, to Alan Friedlander, tation arm of the United Nations Firoze Nathani, Manfred Menzel, Julie Hawkins, Sherry Larkin and Tom Environment Programme (UNEP), the Davide di Mohtarami, Edward Molou, Ogawa; and for providing the picture on world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. -

Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings for 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California

UC San Diego Fish Bulletin Title Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/93g734v0 Authors Pinkas, Leo Gates, Doyle E Frey, Herbert W Publication Date 1974 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISH BULLETIN 161 California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California By Leo Pinkas Marine Resources Region and By Doyle E. Gates and Herbert W. Frey > Marine Resources Region 1974 1 Figure 1. Geographical areas used to summarize California Fisheries statistics. 2 3 1. CALIFORNIA MARINE FISH LANDINGS FOR 1972 LEO PINKAS Marine Resources Region 1.1. INTRODUCTION The protection, propagation, and wise utilization of California's living marine resources (established as common property by statute, Section 1600, Fish and Game Code) is dependent upon the welding of biological, environment- al, economic, and sociological factors. Fundamental to each of these factors, as well as the entire management pro- cess, are harvest records. The California Department of Fish and Game began gathering commercial fisheries land- ing data in 1916. Commercial fish catches were first published in 1929 for the years 1926 and 1927. This report, the 32nd in the landing series, is for the calendar year 1972. It summarizes commercial fishing activities in marine as well as fresh waters and includes the catches of the sportfishing partyboat fleet. Preliminary landing data are published annually in the circular series which also enumerates certain fishery products produced from the catch. -

Training Manual Series No.15/2018

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CMFRI Digital Repository DBTR-H D Indian Council of Agricultural Research Ministry of Science and Technology Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Department of Biotechnology CMFRI Training Manual Series No.15/2018 Training Manual In the frame work of the project: DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals 2015-18 Training Manual In the frame work of the project: DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals 2015-18 Training Manual This is a limited edition of the CMFRI Training Manual provided to participants of the “DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals” organized by the Marine Biotechnology Division of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), from 2nd February 2015 - 31st March 2018. Principal Investigator Dr. P. Vijayagopal Compiled & Edited by Dr. P. Vijayagopal Dr. Reynold Peter Assisted by Aditya Prabhakar Swetha Dhamodharan P V ISBN 978-93-82263-24-1 CMFRI Training Manual Series No.15/2018 Published by Dr A Gopalakrishnan Director, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR-CMFRI) Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute PB.No:1603, Ernakulam North P.O, Kochi-682018, India. 2 Foreword Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi along with CIFE, Mumbai and CIFA, Bhubaneswar within the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and Department of Biotechnology of Government of India organized a series of training programs entitled “DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals”. -

Trematoda: Opecoelidae) with New Records of Trematodes of Marine Fishes from the Pacific Coast of Mexico Revista Mexicana De Biodiversidad, Vol

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Estrada-García, María Angélica; García-Prieto, Luis; Garrido-Olvera, Lorena Description of a new species of Pseudopecoelus (Trematoda: Opecoelidae) with new records of trematodes of marine fishes from the Pacific coast of Mexico Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 89, núm. 1, marzo, 2018, pp. 22-28 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42559253003 Abstract As a part of the revision of unidentified specimens harbored by the Colección Nacional de Helmintos of the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, we studied several specimens of trematodes collected and processed between 1950 and 1980 in marine fishes from several localities along the Pacific coast of Mexico. Among these specimens, we found 1 undescribed species of the genus Pseudopecoelus von Wicklen, 1946 (Pseudopecoelus ibunami n. sp.) of the intestine of the spotted grouper Epinephelus analogus Gill, 1863 (Actinopterygii: Serranidae) from Bahía de La Paz, Baja California Sur. This species is the number 40 known for this genus worldwide and the fifth registered parasitizing fishes from Mexico. The new species differs from the 17 species of Pseudopecoelus with vitelline follicles distributed anteriorly to ventral sucker by having a combination of the following traits: 1) body elongate, narrow, with irregular posterior end, 2) testes and ovary deeply-lobed, and 3) external seminal vesicle reaching only the anterior margin of ventral sucker. In addition, in this study we present new host and geographical records for 6 species of trematodes in marine fishes from Mexico and Pachycreadium gastrocotylum (Manter, 1940) Manter, 1954 is recorded for the first time in this country.