An Institutional Analysis of General Sir Charles Gordon's Counter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilberforce Penned These Words in His Diary: “God Almighty Has Set Before Me Two Great Objects, the Suppression of the Slave Trade and the Reformation of Manners”

“The unweary, unostentation, and inglorious crusade of England against slavery may probably be regarded as among the three or four perfectly virtuous pages comprised in the history of nations.” W. E. Lecky1 ”His standing in the country and in Parliament was unique. No man before, and no one since, has held quite his position. Unconnected to any great family, belonging to no party or faction, holding no office or official position, he was yet regarded by all as among the foremost men of his time, and by many in Parliament as the living embodiment of the national conscience.” Sir Patrick Cormack, M. P.2 A remarkable moment in a remarkable life occurred on Sunday, October 28, 1787 when William Wilberforce penned these words in his diary: “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners”. Indeed, the Lord had set before him two great goals and these goals were to provide the impetus for a life of almost frenetic activity – however it is vital to understand that the man who in these words articulates what would be his life’s work wrote as a man fully and fervently committed to Jesus Christ. If this was a defining moment in his life, his conversion to Christ was the great turning point! This man’s faith was a faith that worked (James 2:1-18). After his death the York Herald of August 3, 1833 said: “His warfare is accomplished, his cause is finished, he kept the faith. Those who regarded him merely as a philanthropist, in the worldly sense of that abused term, know but little of his character.”3 He was, in a very real sense, God’s Politician!4 EARLY LIFE. -

British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Gordon's Ghosts: British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GORDON‘S GHOSTS: BRITISH MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GEORGE GORDON AND HIS LEGACIES, 1885-1960 By STEPHANIE LAFFER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Stephanie Laffer All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Stephanie Laffer defended on February 5, 2010. __________________________________ Charles Upchurch Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Barry Faulk University Representative __________________________________ Max Paul Friedman Committee Member __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For my parents, who always encouraged me… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has been a multi-year project, with research in multiple states and countries. It would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the libraries and archives I visited, in both the United States and the United Kingdom. However, without the support of the history department and Florida State University, I would not have been able to complete the project. My advisor, Charles Upchurch encouraged me to broaden my understanding of the British Empire, which led to my decision to study Charles Gordon. Dr. Upchurch‘s constant urging for me to push my writing and theoretical understanding of imperialism further, led to a much stronger dissertation than I could have ever produced on my own. -

Bibliography of the Gordons. Section I

. /?• 26'tf National Library of Scotland *B000410047* j -> :s -f r*. n •:-, "'.-? g n u w ta» i « Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/bibliographyofgo1924bull Witjj Mt>. J. Malcolm BalloeB'? Compliments. 4r b^&tf'&^f. tie- f *Zn%i:r m£lvi*9&&A»d6&0! Aberdeen University Studies : No. 94 Bibliography of the Gordons —— University of Aberdeen. UNIVERSITY STUDIES. General Editor : P. J. Anderson, LL.B., Librarian to the University. 1900-1913. Nos. 1-63. 1914. No. 64. Zoological Studies. Professor Thomson and others. Ser. VIII. No. 65.—Highland Host of 1678. J. R. Elder, D.Litt. „ No. 66. Concise Bibliography of Aberdeen, Banff, and Kincardine. J. F. Kellas Johnstone. „ No. 67. Bishop Burnet as Educationist. John Clarke, M.A. 1915. No. 68. Territorial Soldiering in N.E. Scotland. J. M. Bulloch, M.A. ,, No. 69. Proceedings of the A natomical and Anthropological Society, 1908-14. ,, No. 70. Zoological Studies. Professor Thomson and others. Ser. IX. 1, No. 71. Aberdeen University Library Bulletin. Vol. II. 1916. No. 72. Physiological Studies. Professor Mac William, F.R.S., and others. Ser. I. 1917. No. 73. Concise Bibliography of Inverness-shire. P. J. Anderson. i, No. 74. The Idea of God. Professor Pringle-Pattison. (Gifford Lectures, 1912-13.) „ No. 75. Interamna Borealis. W. Keith Leask, M.A. ,, No. 76. Roll of Medical Service of British Army. Col. W. Johnston, C.B., LL.D. 1918. No. 77. Aberdeen University Library Bulletin. Vol. HI. „ No. 78. Moral Values and the Idea of God. -

Utd^L. Dean of the Graduate School Ev .•^C>V

THE FASHODA CRISIS: A SURVEY OF ANGLO-FRENCH IMPERIAL POLICY ON THE UPPER NILE QUESTION, 1882-1899 APPROVED: Graduate ttee: Majdr Prbfessor ~y /• Minor Professor lttee Member Committee Member irman of the Department/6f History J (7-ZZyUtd^L. Dean of the Graduate School eV .•^C>v Goode, James Hubbard, The Fashoda Crisis: A Survey of Anglo-French Imperial Policy on the Upper Nile Question, 1882-1899. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December, 1971, 235 pp., bibliography, 161 titles. Early and recent interpretations of imperialism and long-range expansionist policies of Britain and France during the period of so-called "new imperialism" after 1870 are examined as factors in the causes of the Fashoda Crisis of 1898-1899. British, French, and German diplomatic docu- ments, memoirs, eye-witness accounts, journals, letters, newspaper and journal articles, and secondary works form the basis of the study. Anglo-French rivalry for overseas territories is traced from the Age of Discovery to the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, the event which, more than any other, triggered the opening up of Africa by Europeans. The British intention to build a railroad and an empire from Cairo to Capetown and the French dream of drawing a line of authority from the mouth of the Congo River to Djibouti, on the Red Sea, for Tied a huge cross of European imperialism over the African continent, The point of intersection was the mud-hut village of Fashoda on the left bank of the White Nile south of Khartoum. The. Fashoda meeting, on September 19, 1898, of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, representing France, and General Sir Herbert Kitchener, representing Britain and Egypt, touched off an international crisis, almost resulting in global war. -

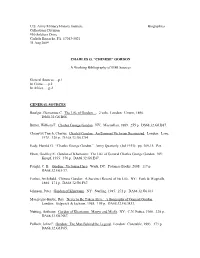

Gordon, Charles.Pdf

U.S. Army Military History Institute Biographies Collections Division 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 31 Aug 2009 CHARLES G. “CHINESE” GORDON A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources General Sources.…p.1 In China…..p.2 In Africa…..p.2 GENERAL SOURCES Boulger, Demetrius C. The Life of Gordon…. 2 vols. London: Unwin, 1896. DS68.32.G6.B68. Butler, William F. Charles George Gordon. NY: Macmillan, 1889. 255 p. DS68.32.G6.B87. Chenevix Tench, Charles. Charley Gordon: An Eminent Victorian Reassessed. London: Lane, 1978. 320 p. DA68.32.G6.C54. Eady, Harold G. “Charles George Gordon.” Army Quarterly (Jul 1933): pp. 309-15. Per. Elton, Godfrey E. Gordon of Khartoum: The Life of General Charles George Gordon. NY: Knopf, 1955. 376 p. DA68.32.G6.E47. Faught, C. B. Gordon: Victorian Hero. Wash, DC: Potomac Books, 2008. 117 p. DA68.32.G6.F37. Forbes, Archibald. Chinese Gordon: A Succinct Record of his Life. NY: Funk & Wagnalls, 1884. 171 p. DA68.32.G6.F67. Johnson, Peter. Gordon of Khartoum. NY: Sterling, 1985. 272 p. DA68.32.G6.J63. Macgregor-Hastie, Roy. Never to Be Taken Alive: A Biography of General Gordon. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1985. 195 p. DA68.32.G6.M33. Nutting, Anthony. Gordon of Khartoum: Martyr and Misfit. NY: C.N. Potter, 1966. 338 p. DA68.32.G6.N87. Pollock, John C. Gordon: The Man Behind the Legend. London: Constable, 1993. 373 p. DA68.32.G6.P65. Charles Gordon p.2 Stachey, Lytton. Eminent Victorians: Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold, General Gordon. NY: Modern Lib, 1918. -

A Camaraderie of Confidence Books by John Piper

A Camaraderie of Confidence Books by John Piper Battling Unbelief Bloodlines: Race, Cross, and the Christian Brothers, We Are Not Professionals Contending for Our All (Swans 4) The Dangerous Duty of Delight The Dawning of Indestructible Joy Desiring God Does God Desire All to Be Saved? Don’t Waste Your Life Fifty Reasons Why Jesus Came to Die Filling Up the Afflictions of Christ (Swans 5) Finally Alive Five Points Future Grace God Is the Gospel God’s Passion for His Glory A Godward Heart A Godward Life The Hidden Smile of God (Swans 2) A Hunger for God The Legacy of Sovereign Joy (Swans 1) Lessons from a Hospital Bed Let the Nations Be Glad! A Peculiar Glory The Pleasures of God The Roots of Endurance (Swans 3) Seeing and Savoring Jesus Christ Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully (Swans 6) Spectacular Sins The Supremacy of God in Preaching A Sweet and Bitter Providence Taste and See Think This Momentary Marriage What Jesus Demands from the World What’s the Difference? When I Don’t Desire God The Swans Are Not Silent Book Seven A Camaraderie of Confidence The Fruit of Unfailing Faith in the Lives of Charles Spurgeon, George Müller, and Hudson Taylor John Pi Per ® WHEATON, ILLINOIS A Camaraderie of Confidence: The Fruit of Unfailing Faith in the Lives of Charles Spurgeon, George Müller, and Hudson Taylor Copyright © 2016 by Desiring God Foundation Published by Crossway 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. -

General Gordon's Last Crusade: the Khartoum Campaign and the British Public William Christopher Mullen Harding University, [email protected]

Tenor of Our Times Volume 1 Article 9 Spring 2012 General Gordon's Last Crusade: The Khartoum Campaign and the British Public William Christopher Mullen Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mullen, William Christopher (Spring 2012) "General Gordon's Last Crusade: The Khartoum Campaign and the British Public," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 1, Article 9. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol1/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENERAL GORDON'S LAST CRUSADE: THE KHARTOUM CAMPAIGN AND THE BRITISH PUBLIC by William Christopher Mullen On January 26, 1885, Khartoum fell. The fortress-city which had withstood an onslaught by Mahdist forces for ten months had become the last bastion of Anglo-Egyptian rule in the Sudan, represented in the person of Charles George Gordon. His death at the hands of the Mahdi transformed what had been a simple evacuation into a latter-day crusade, and caused the British people to re-evaluate their view of their empire. Gordon's death became a matter of national honor, and it would not go un avenged. The Sudan had previously existed in the British consciousness as a vast, useless expanse of desert, and Egypt as an unfortunate financial drain upon the Empire, but no longer. -

John Wesley's Thoughts Upon Slavery

'John Wesley's Thoughts Upon Slavery and the Language of the Heart', The Bulletin 0/the John Rylands University Library 0/ Manchester, 85:2-3 (Summer/Autumn 2003), 269-84. John Wesley's Thoughts upon slavery and the language of the heart BRYCCHAN CAREY It is a commonplace, although one not often examined closely, that John Wesley was a lifelong opponent of slavery. Such claims originate with Wesley himself. 'Ever since I heard of it first', he wrote to Granville Sharp in October 1787, 'I felt a perfect detestation of the horrid Slave Trade'. I Whether that is true is impossible to know. What is certain is that Wesley actively opposed the slave trade from the early 1770s onwards. Scholars of both Methodism and of abolitionism have often noted in passing his contributions to the accelerating abolition movement, which have survived in the form of a pamphlet, a group of letters, and a number of Journal entries. As yet, however, these contributions have evaded extended analysis.2 Accordingly, my intention in this essay is twofold. In the first section, I chart the development of Wesley's views on slavery and assess his place in the development of the British abolition movement. In the second section, I examine Wesley's main contribution to that movement, his pamphlet Thoughts upon slavery, written in 1774, and read it not only as polemic, but also as 'literature' to demonstrate that Wesley's sentimental style is as important as his moral, religious and economic arguments. Indeed, Wesley, despite objecting to sentimental writing in his Journal, is in fact one of the first major writers on slavery to use a sentimental rhetoric to make arguments against it: an important innovation, since much of the ensuing debate was conducted in exactly those sentimental terms. -

Jaroslav Valkoun the Sudanese Life of General Charles George Gordon1

Anton Prokesch von Osten… | Miroslav Šedivý 48 | 49 He in no way gained the general esteem of his colleagues by assentation as claimed by Jaroslav Valkoun Hammer-Purgstall but, on the contrary, by raising arguments even in contradiction with the opinion prevailing at the Viennese Chancellery at the time, as happened in 1832. The validity of his opinions considerably improved his position and increased Me- tternich’s respect. Consequently, though more well-disposed towards Mohammed Ali than the Austrian chancellor himself, Prokesch continued to play the role of Metterni- ch’s adviser in the following years, and he did so either by his written comments to Laurin’s reports or through personal meetings with the chancellor in Vienna. With his two memoirs from late 1833 Prokesch also significantly influenced Metternich’s Egyp- tian policy for several years to come. Prokesch’s considerable reputation was so high that it survived Metternich’s fall in March 1848 and later brought him to the diplomatic post in Constantinople where, as mentioned above, he represented the Austrian and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1855 to 1871. References BEER, Adolf (1883): Die orientalische Politik Österreichs seit 1773. Prag, Leipzig: E. Tempsky und G. Freytag. BERTSCH, Daniel (2005): Anton Prokesch von Osten (1795–1876). Ein Diplomat Österreichs in Athen und an der Hohen Pforte. Beiträge zur Wahrnehmung des Orients im Europa des 19. Jahrhunderts. München: R. Ol- The Sudanese life of General denbourg Verlag. 1 FICHTNER, Paula Sutter (2008): Terror and Toleration. The Habsburg Empire Confronts Islam, 1526–1850. Charles George Gordon London: Reaktion Books. -

The Mahdiyya, Bib

BIBLIOGRAPHIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE MAHDIST STATE IN THE SUDAN (1881-1898) AHMED IBRAHIM ABU SHOUK The Sudanese Mahdiyya was a movement of social, economic and political protest, launched in 1881 by Mu˛ammad A˛mad b. fiAbd Allh (later Mu˛ammad al- Mahdı) against the Turco-Egyptian imperialists who had ruled the Sudan since 1821. After four years of struggle the Mahdist rebels overthrew the Turco-Egyptian administration and established their own ‘Islamic and national’ government with its capital in Omdurman. Thus from 1885 the Mahdist regime maintained sovereignty and control over the Sudanese territories until its existence was terminated by the Anglo-Egyptian imperial forces in 1898. The purpose of this article is first to give a brief survey of the primary sources of Mahdist history, secondly to trace the development of Mahdist studies in the Sudan and abroad, and finally to present a detailed bibliography of the history of the Mahdist revolution and state, with special reference to published sources (primary and secondary) and conference papers. Bibliographic overview The seventeen years of Mahdist rule in the Sudan produced a large number of published and unpublished primary textual sources on the history of the revolution and its state. Contri- butions from ‘Mahdist intellectuals’ in the Sudan were products of the state written in defence of the ideals of Mahdist ideology and the achievements of the Mahdi and his successor, the Khalifa fiAbdallhi. The Mahdi himself left a Sudanic Africa, 10, 1999, 133-168 134 AHMED IBRAHIM ABU SHOUK corpus of literary works, which manifest his own teachings, proclamations, sermons and judgements issued on various occasions. -

Some Corner of a Chinese Field: the Politics of Remembering Foreign Veterans of the Taiping Civil War

Jonathan Chappell Some corner of a Chinese field: the politics of remembering foreign veterans of the Taiping Civil War Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Chappell, Jonathan (2018) Some corner of a Chinese field: the politics of remembering foreign veterans of the Taiping Civil War. Modern Asian Studies. ISSN 0026-749X (In Press) DOI: 10.1017/S0026749X16000986 © 2018 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/87882/ Available in LSE Research Online: May 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Some Corner of a Chinese Field: The Politics of Remembering Foreign Veterans of the Taiping Civil War* Short title: Politics of Remembering Foreign Veterans Abstract The memory of the foreign involvement in the Taiping war lasted long after the fall of the Taiping capital at Nanjing in 1864. -

Billy Graham, Anticommunism, and Vietnam

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2017 "A Babe in the Woods?": Billy Graham, Anticommunism, and Vietnam Daniel Alexander Hays Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hays, Daniel Alexander, ""A Babe in the Woods?": Billy Graham, Anticommunism, and Vietnam" (2017). Masters Theses. 2521. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2521 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - " _...,,,,,;.._;'[£"' -�,,� �·�----�-·--·- - The Graduate School� EAs'rER,NILLINOIS UNIVERSITY" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis.