Management of Bladder Cancer Following Solid Organ Transplantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How I Do It Open Distal Ureteroureterostomy for Ectopic Ureters in Infants with Duplex Systems and No Vesicoureteral Reflux Under 6 Months of Age ______

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE Vol. 47 (3): 610-614, May - June, 2021 doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.0742 How I do it open distal ureteroureterostomy for ectopic ureters in infants with duplex systems and no vesicoureteral reflux under 6 months of age _______________________________________________ Yuding Wang 1, Luis H. Braga 1 1 Departament of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO We describe a step by step technique for open distal ureteroureterostomy (UU) in infants Luis H. Braga less than 6 months presenting with duplex collecting system and upper pole ectopic https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3953-7353 ureter in the absence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Keywords: Vesico-Ureteral Reflux; Ureter; Infant BACKGROUND Int Braz J Urol. 2021; 47: 610-4 Approximately 70% of ectopic ureters occur with ureteral duplication, with 80% of cases including contralateral duplication. They are found mainly _____________________ in Caucasian children and are four to seven times more common in females Submitted for publication: August 20, 2020 (1). The typical patient used to present with recurrent UTIs, flank pain from obstruction, or continuous incontinence (2). However, currently, the great ma- jority of these patients are discovered incidentally on routine investigation of _____________________ prenatal hydronephrosis (2). Accepted after revision: It has been common practice to defer surgical intervention of the September 10, 2020 patients diagnosed in the neonatal period until 12 months of age. Possi- ble management options include upper pole heminephrectomy, pyelou- reterostomy, common sheath ureteral reimplantation, upper pole ureteral _____________________ Published as Ahead of Print: clipping, and ipsilateral proximal or distal ureteroureterostomy. The deci- October 20, 2020 sion towards an ablative versus a reconstructive approach has traditionally been influenced by upper pole function, as well as surgeon preference. -

Urology Privilege

SAN GORGONIO MEMORIAL HOSPITAL PRIVILEGE DELINEATION LIST UROLOGY NAME OF APPLICANT:____________________________________ DATE:________________ YEAR OF BOARD CERTIFICATION/RECERTIFICATION___________________________ PRIVILEGES QUALIFICATIONS/CRITERIA CATEGORY CATEGORY I USUAL AND CUSTOMARY PRIVILEGES (Procedures considered included in minimal formal training.) QUALIFICATIONS: 1. Successful completion of an accredited Urology residency training program, AND, 2. Board qualified/certified by the American Board of Urology with specific training and recent experience in privileges requested, OR, (in lieu of Board Certification) 3. Demonstrate comparable competency to perform the privileges requested based on proctoring reports, reference letters, activity/operative reports or other documentation acceptable to the Surgical Service, AND have been practicing in Urology for the past 5 years. 4. Privileges will be proctored per Surgical Service Rules and Regulations. MODERATE SEDATION I.V. MEDICATIONS FOR SPECIAL PROCEDURES (All medications with potential loss of protective reflexes regardless of route of administration) QUALIFICATIONS: Physicians with Urology privileges, by virtue of their specialty training are qualified for Moderate Sedation privileges as requested below, but must continue to demonstrate current competency as outlined in the Medical Staff Rules and Regulations. R # Done D P/O G CATEGORY 1 - USUAL AND CUSTOMARY PRIVELEGES 24 mos CORE PRIVILEGES: For the initial evaluation and management of patients of all ages for admission, work-up, pre and post-operative care, and ordering and prescribing medications per DEA certificate ENDOSCOPY: 1. Urethroscopy 2. Cystoscopy 3. Ureteroscopy 4. Nephroscopy RENAL: 5. Flank exploration, nephrectomy and/or partial 6. Removal of stones 7. Reconstruction 8. Trauma repair 9. Pyelotomy, Pyelolithotomy, Pyeloplasty 10. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection 11. Nephroureterectomy 12. -

Obstruction of the Urinary Tract 2567

Chapter 540 ◆ Obstruction of the Urinary Tract 2567 Table 540-1 Types and Causes of Urinary Tract Obstruction LOCATION CAUSE Infundibula Congenital Calculi Inflammatory (tuberculosis) Traumatic Postsurgical Neoplastic Renal pelvis Congenital (infundibulopelvic stenosis) Inflammatory (tuberculosis) Calculi Neoplasia (Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma) Ureteropelvic junction Congenital stenosis Chapter 540 Calculi Neoplasia Inflammatory Obstruction of the Postsurgical Traumatic Ureter Congenital obstructive megaureter Urinary Tract Midureteral structure Jack S. Elder Ureteral ectopia Ureterocele Retrocaval ureter Ureteral fibroepithelial polyps Most childhood obstructive lesions are congenital, although urinary Ureteral valves tract obstruction can be caused by trauma, neoplasia, calculi, inflam- Calculi matory processes, or surgical procedures. Obstructive lesions occur at Postsurgical any level from the urethral meatus to the calyceal infundibula (Table Extrinsic compression 540-1). The pathophysiologic effects of obstruction depend on its level, Neoplasia (neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and other retroperitoneal or pelvic the extent of involvement, the child’s age at onset, and whether it is tumors) acute or chronic. Inflammatory (Crohn disease, chronic granulomatous disease) ETIOLOGY Hematoma, urinoma Ureteral obstruction occurring early in fetal life results in renal dys- Lymphocele plasia, ranging from multicystic kidney, which is associated with ure- Retroperitoneal fibrosis teral or pelvic atresia (see Fig. 537-2 in Chapter 537), to various -

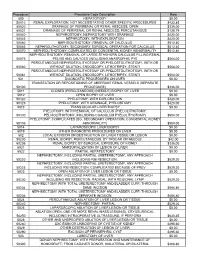

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Ureteric Reconstruction and Replacement Ralph Peeker

Ureteric reconstruction and replacement Ralph Peeker Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden Purpose of review Correspondence to Dr Ralph Peeker, President of The To review the recent advances on ureteric reconstruction and replacement, in particular, Swedish Association of Urology, Senior Consultant, ileal ureteric replacement and laparoscopic and robotic-assisted ureteral Associate Professor of Urology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, 413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden reconstruction. Tel: +46 313421000; fax: +46 31821741; Recent findings e-mail: [email protected] Recently, the ureteric replacement with bowel has been carefully assessed by several Current Opinion in Urology 2009, 19:563–570 authors, and the results are quite impressive. Also, very recent studies on laparoscopic and robotic-assisted ureteral repair have been published. Outcomes appear very promising, allowing for a faster recovery and shorter hospital stay for the patient. Summary Today, we can conclude that the field of ureteric reconstruction and replacement is still evolving. Old techniques are supported by an increasing degree of evidence, and new, more minimally invasive surgical strategies emerge. Clearly, there are some disadvantages as well as difficulties to overcome with the new techniques; however, recent studies appear to present promising results. Keywords iatrogenic injury, surgery, ureter, ureteral reconstruction, ureteral repair, ureteral replacement Curr Opin Urol 19:563–570 ß 2009 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 0963-0643 suggested that the introduction of laparoscopy in benign Introduction gynaecological surgery could possibly have increased The reasons necessitating reconstruction or replacement the frequency of injuries [8]. The patients risk side- of the ureter are manifold and include different kinds of effects such as infections, leakage and loss of renal trauma, ureteric removal due to extensive tumour growth function. -

Review of the Current Management of Upper Urinary Tract Injuries by the EAU Trauma Guidelines Panel

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 67 (2015) 930–936 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com Guidelines Review of the Current Management of Upper Urinary Tract Injuries by the EAU Trauma Guidelines Panel Efraim Serafetinides a,*, Noam D. Kitrey b, Nenad Djakovic c, Franklin E. Kuehhas d, Nicolaas Lumen e, Davendra M. Sharma f, Duncan J. Summerton g a Department of Urology, Asklipieion General Hospital, Athens, Greece; b Department of Urology, Chaim Sheba Medical Centre, Tel-Hashomer, Israel; c Department of Urology, Mu¨hldorf General Hospital, Mu¨hldorf am Inn, Germany; d London Andrology Institute, London, UK; e Department of Urology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium; f Urology Department, St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK; g Department of Urology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Leicester, UK Article info Abstract Article history: Context: The most recent European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on urologi- Accepted December 18, 2014 cal trauma were published in 2014. Objective: To present a summary of the 2014 version of the EAU guidelines on upper urinary tract injuries with the emphasis upon diagnosis and treatment. Keywords: Evidence acquisition: The EAU trauma guidelines panel reviewed literature by a Med- Kidney trauma/injury line search on upper urinary tract injuries; publication dates up to December 2013 were Ureteral trauma/injury accepted. The focus was on newer publications and reviews, although older key references could be included. Blunt trauma Evidence synthesis: A full version of the guidelines is available in print and online. Upper urinary tract trauma Blunt trauma is the main cause of renal injuries. The preferred diagnostic modality of Penetrating trauma renal trauma is computed tomography (CT) scan. -

Milestones in Robotic Kidney Surgery at Henry Ford Hospital

Milestones in Robotic Kidney Surgery at Henry Ford Hospital Craig Rogers MD, FACS Director of Renal Surgery Director of Urologic Oncology Fellowship Director Vattikuti Urology Institute, Detroit, Michigan USA My Road to HFH Senior Staff: 2007 Fellowship: Urologic Oncology Residency M.D. Building on a Successful Robotic Prostatectomy Program • 1st Robotic Prostatectomy program and largest experience (>6000 cases) • Techniques developed: – Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy (VIP)-2000 – “Veil” nerve sparing-2003 – Urethral catheter-free technique – Randomized Controlled Trial for double layer anastomosis Building a Legacy in Robotic Kidney Surgery • Among world’s largest experience • Firsts at HFH: – First live webcast of Robotic Partial Nephrectomy (RPN) via OR Live, 2007 – Barbed suture reconstruction of kidney during RPN – Developed Robotic bulldog clamps and robotic ultrasound probe – First live telecast of RPN at AUA meeting from HFH, 2008-9 – First “twittered” RPN (featured CNN and NPR) 2009 – First RPN with cooling and early tumor evaluation 2012. Developed “cooling syringe” – Hosted first AUA Hands-on course for small renal mass, 2014 – First endovascular removal of IVC tumor thrombus to facilitate robotic cytoreductive nephrectomy, 2014 Developing a World-class Robotic Kidney Surgery Program • Kuala Lumpur, “Mission Malaysia” 2005, 2007 (40 robotic cases in 7 days) • “Renal Week” Sunnyvale, CA 2007 Developed model to create pseudotumors in pig and cadaver kidneys (Eun et al, J Urol 2008) Performed robotic partial nephrectomy in -

Treating Ureteric Obstruction with Ureteroscope

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2017; 21: 5330-5336 Treating ureteric obstruction secondary to gynecological disease assisted with retrograde ureteroscopic stenting J.-C. CHEN1, S.-X. ZHU1, L.-G. REN2, J. CHEN2, W. ZHANG2 1Department of Urologic Oncology, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, No. 1, Gongshu District, Hangzhou, China 2Department of Urologic Oncology, Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province, Xihu District, Hangzhou, China Abstract. – OBJECTIVE: To analyze the techni- logical factor is one of the most common causes, cal experience and clinical efficacy of ureteroscop- including ureteral iatrogenic injury and gyne- ic treatment of middle and lower ureteral obstruc- cological tumors. Ureteral iatrogenic injury is a tion due to gynecological disease. potential complication in gynecological surgery PATIENTS AND METHODS: From January 2007 for tumors, which has increased in the past 20 to December 2015, 58 cases of ureteral obstruction w e r e c o l l e c t e d i n 5 5 p a t i e n t s c a u s e d b y g y n e c o l o g - years and is mostly caused by gynecologically ical factors. 19 cases had the history of gynecolog- laparoscopic surgery located in the lower seg- ical iatrogenic injury and 39 cases were secondary ment of ureter1. At the same time, gynecological to gynecological tumors. Different situations of lu- tumors tend to invade into pelvic cavity and lead minal stenosis included obliteration, suture pene- to an infringement or oppression to ureter. The tration, transection and unrecognized ureteral ori- development of malignant ureteric obstruction is fice. -

Retrograde Flexible Ureteroscopy-Assisted

CASE REPORT – OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 20 (2016) 77–79 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery Case Reports journa l homepage: www.casereports.com Retrograde flexible ureteroscopy-assisted retroperitoneal laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy for refractory ureteral stricture: A case report ∗ Nobuo Tsuru , Soichi Mugiya, Shigenori Sato Department of Urology and Endoscopic Surgery Center, Suzukake Central Hospital, Hamamatsu, Japan a r a t i b s c t l e i n f o r a c t Article history: INTRODUCTION: Laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy (UU) is a preferred and valid minimally invasive pro- Received 17 July 2015 cedure for treatment of benign ureteral strictures. In some cases with chronic inflammation or after Received in revised form 14 January 2016 repeated endoscopic ureteral surgery, it is difficult to identify the location of a ureteral stricture. Accepted 16 January 2016 PRESENTATION OF CASE: We report a case of 48-year-old man with an impacted stone after laparoscopic Available online 22 January 2016 partial nephrectomy. Although transurethral lithotripsy (TUL) was performed, the ureteral stricture did not improve by subsequent endoscopic ureteral Holmium laser incision and balloon dilation. Keywords: DISCUSSION: To simultaneously identify the exact location of the constriction, we performed retroperi- Laparoscopy toneal laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy with intraoperative observations via super-slim flexible Retroperitoneal approach Ureteroureterostomy fiberoptic ureteroscopy retrograde. Ureteral stricture CONCLUSIONS: Accurate identification of the ureteral stricture via observation by laparoscopy and obser- Ureteroscopy vation by ureteroscopy was feasible. In contrast to the use of a rigid ureteroscopy, flexible fiberoptic ureteroscopy did not require placing the patient in an unnatural position. -

Narrative Review of the Current Management of Radiation-Induced Ureteral Strictures of the Pelvis

17 Review Article Page 1 of 17 Narrative review of the current management of radiation-induced ureteral strictures of the pelvis Pooja Srikanth1^, Hannah E. Kay1^, Adan N. Tijerina1^, Arjun V. Srivastava1^, Aaron A. Laviana1,2^, J. Stuart Wolf Jr1,2^, E. Charles Osterberg1,2^ 1University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin, TX, USA; 2Dell Medical School Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, and Ascension Seton Hospital Network, Austin, TX, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: EC Osterberg, P Srikanth; (II) Administrative support: EC Osterberg, AA Laviana, JS Wolf Jr; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: P Srikanth, HE Kay, AN Tijerina, AV Srivastava; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: P Srikanth, HE Kay, AN Tijerina, AV Srivastava; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Pooja Srikanth. University of Texas Dell Medical School, 1501 Red River St., Austin, TX 78712, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Radiation therapy to the pelvis is indicated for cervical, prostate, rectal, and gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies. A rare, but known adverse effect of this treatment is radiation-induced ureteral stricture (RIUS). RIUS can cause infection, hydronephrosis, kidney stone formation, and ultimately, renal failure. Management of RIUS is a challenge to urologists as the strictures tend to be long, bilateral, and ischemic in etiology. Management of RIUS is divided into endoscopic, open, and minimally invasive techniques. Stents and percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) tubes are generally used as temporizing measures until definitive repair, but they may be a long-term option for patients unfit for surgery. -

Ureteroarterial Fistula After Urinary Diversion

■ 原 著 日血外会誌 14:583–586,2005 Ureteroarterial Fistula after Urinary Diversion Osamu Sato1, Hirohiko Sakamoto2, Yoichi Tanaka2, Takeshi Sekine2 and Yotsuo Higashi3 Abstract: Ureteroarterial fistula, a serious complication that sometimes arises after urinary diversion surgery, is fatal if untreated. The purpose of this study was to investigate the incidence and course of this condition and seek the method of prevention. We retrospectively reviewed the hospital records of 118 patients who underwent urinary diversion surgery at Saitama Cancer Center between 1994 and 1999. The urological procedure was cutaneous ureterostomy in 82 patients and ileal conduit in 36. Among those patients, four developed ureteroarterial fistula. The urinary diversion procedure used in these four patients was cutaneous ureterostomy and all the ureters had been stented, thus the incidence of fistula formation was 4.9% among the 82 patients with cutaneous ureterostomies. Dacron patch closure of the aortic defect in the first patient resulted in infection of the graft. Ligation of the aorta or iliac artery and extraanatomical revascularization was performed in two. One fistula was directly closed with sutures. Two patients survived the operation. We concluded that the rate of fistula formation between the ureter and a major artery within one year after surgery may reach nearly 5% if a cutaneous ureterostomy is created and the catheterized ureter crosses the major artery. In order to prevent fistula formation, we employed the omental cushion method, in which the greater omentum was interposed between the ureter and aorta or iliac arteries. After adoption of this method, there has been no fistula formation. Further observation is, however, necessary. -

Transperitoneal Laparoscopic Ureteroureterostomy with Excision of the Compressed Ureter for Retrocaval Ureter and Review of Literature

Original Article - Endourology/Urolithiasis Investig Clin Urol 2019;60:108-113. https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2019.60.2.108 pISSN 2466-0493 • eISSN 2466-054X Transperitoneal laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy with excision of the compressed ureter for retrocaval ureter and review of literature Ill Young Seo1, Tae Hoon Oh1, Seung Hyun Jeon2 1Department of Urology, Institute of Wonkwang Medical Science, Wonkwang University School of Medicine and Hospital, Iksan, 2Department of Urology, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea Purpose: We present surgical techniques and operative results of laparoscopic reconstruction for patients with retrocaval ureter (RCU) and review similar papers. Materials and Methods: Ten patients with RCU were enrolled in this study from April 2005 to January 2017. The mean age of 7 males and 3 females was 40.5 years old. The chief complaint was flank pain in 6 patients; the remaining patients were detected incidentally. All patients showed hydronephrosis and typical S-shaped deformity of the ureter on imaging studies. Five patients showed obstructed patterns on the renal scans. Two surgeons performed laparoscopic ureteroureterostomies with transperitoneal approaches including excision of the compressed ureter. Double-J ureteral stents were inserted intraoperatively. The operative and follow-up results were checked and compared with published papers. Results: All laparoscopic reconstructions were successfully completed without conversion to open surgery. The mean operative time was 199.6 minutes. The estimated blood loss was 154.4 mL. No operative complications were encountered. There were no obstruction and symptom after the mean follow-up of 40.7 months. We found 7 papers from PubMed, which had more than five cases of laparoscopic reconstruction of RCU.