Rt Hon John Healey, Shadow Health Secretary Speech to IPPR – 22 June 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Emily Thornberry

1 EMILY THORNBERRY ANDREW MARR SHOW, 5TH FEBRUARY, 2017 I/V EMILY THORNBERRY, SHADOW FOREIGN SECRETARY Andrew Marr: We've been seeing this week the first signs of canvassers stumbling around the by-election centres of Stoke Central and Copeland. That's where Labour will hear a meaningful verdict on their recent performance. The Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry joins me now. Emily Thornberry, 47 Labour MPs, including 10 front benchers voted against the whip or didn’t support the whip this week. Were they right do so? You have a remain constituency. Emily Thornberry: Listen, I know your narrative is, as you said at the top of the programme, that we are hopelessly divided. I really don’t think that is fair. Let me say why. The Labour Party is a national party and we represent the nation and the nation is divided on this, and it is very difficult and many MPs representing majority remain constituencies have this very difficult balancing act between do I represent my constituency, or do I represent the nation? Labour, as a national party, have a clear view. We have been given our instructions. We lost the referendum. We fought to stay in Europe but the public have spoken and so we do as we’re told. But the important thing now is not to give Theresa May a blank cheque, we have to make sure we get the right deal for the country. Andrew Marr: Absolutely, and I want to come onto that, but it sounds as if you’re saying that you understand the motives of those Labour MPs who voted with their conscience against triggering Article 50 and will carry on doing so. -

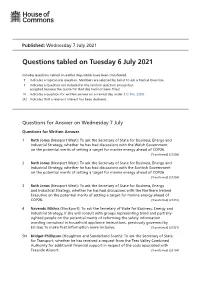

Questions Tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021

Published: Wednesday 7 July 2021 Questions tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 7 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Welsh Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27308) 2 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Scottish Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27309) 3 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Northern Ireland Executive on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27310) 4 Navendu Mishra (Stockport): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, if she will consult with groups representing blind and partially- sighted people on the potential merits of reforming the safety information wording contained in household appliance instructions, previously governed by EU law, to make that information more inclusive. -

Survey Report

YouGov / Election Data Survey Results Sample Size: 1096 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 27th February - 3rd March 2017 EU Ref Vote 2015 Vote Age Gender Social Grade Region Membership Length Not Rest of Midlands / Pre Corbyn After Corbyn Total Remain Leave Lab 18-39 40-59 60+ Male Female ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Lab South Wales leader leader Weighted Sample 1096 961 101 859 237 414 393 288 626 470 743 353 238 322 184 294 55 429 667 Unweighted Sample 1096 976 96 896 200 351 434 311 524 572 826 270 157 330 217 326 63 621 475 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION: Westminster [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote or don't know] Con 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 Lab 92 92 95 92 93 92 92 93 92 94 90 97 94 90 94 93 93 89 95 Lib Dem 5 6 1 6 3 5 5 6 7 3 7 2 5 8 4 4 4 9 3 UKIP 0 0 4 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 Other 1 2 0 1 3 2 1 1 1 3 2 0 1 2 1 1 3 1 2 Other Parties Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote or don't know] SNP/ PCY 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 Green 1 1 0 1 2 1 1 1 0 2 2 0 1 2 1 1 0 1 1 BNP 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Respect 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 © 2017 YouGov plc. -

Conduct of Ms Emily Thornberry

House of Commons Committee on Standards and Privileges Conduct of Ms Emily Thornberry Eleventh Report of Session 2005–06 Report and Appendix, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 27 June 2006 HC 1367 Published on 28 June 2006 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Committee on Standards & Privileges The Committee on Standards and Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to oversee the work of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards; to examine the arrangements proposed by the Commissioner for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of the Register of Members’ Interests and any other registers of interest established by the House; to review from time to time the form and content of those registers; to consider any specific complaints made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests referred to it by the Commissioner; to consider any matter relating to the conduct of Members, including specific complaints in relation to alleged breaches in the Code of Conduct which have been drawn to the Committee’s attention by the Commissioner; and to recommend any modifications to the Code of Conduct as may from time to time appear to be necessary. Current membership Rt Hon Sir George Young Bt MP (Conservative, North West Hampshire) (Chairman) Rt Hon Kevin Barron MP (Labour, Rother Valley) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton & Ripon) Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) Nick Harvey MP (Liberal Democrat, North Devon) Mr Brian Jenkins MP (Labour, Tamworth) Mr Elfyn Llwyd MP (Plaid Cymru, Meirionnydd Nant Conwy) Mr Chris Mullin MP (Labour, Sunderland South) The Hon Nicholas Soames MP (Conservative, Mid Sussex) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) Powers The constitution and powers of the Committee are set out in Standing Order No. -

Yougov / the Sunday Times Survey Results

YouGov / The Sunday Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1011 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 7th - 9th September 2010 1st Preference - September 2010 1st Preference - July 2010 September Choice July Choice Gender Age Diane Andy David Ed Diane Andy David Ed David Ed David Ed Total Ed Balls Ed Balls Male Female 18-34 35-54 55+ Abbott Burnham Miliband Miliband Abbott Burnham Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Weighted Sample 1008 106 86 91 354 287 99 45 65 244 209 431 474 320 340 577 432 331 303 374 Unweighted Sample 1011 102 89 97 344 296 93 45 69 239 221 429 485 310 353 654 357 307 317 387 % %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 1st Preference - September 2010 [Excluding Don't know and Wouldn't Vote] David Miliband 38 0001000824 9 79 16 83 0 68 11 36 42 41 39 35 Ed Miliband 31 00001001114 13 11 69 1 62 11 50 31 31 33 28 33 Diane Abbott 11 1000000702 3144164181112131111 Andy Burnham 10 001000029 66 4 6 7 10 10 10 12 7 8 10 11 Ed Balls 9 0100000852 10 5 6 5 12 7 11 10 8 5 13 10 Weighted Sample 846 92 82 84 320 268 84 41 55 214 186 384 427 279 296 493 353 280 258 308 Unweighted Sample 849 90 85 89 308 277 80 41 58 207 199 380 438 268 309 555 294 260 266 323 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 2nd Preference - September 2010 [Excluding Don't know and Wouldn't Vote] Ed Miliband 30 53 48 34 43 0 42 32 25 33 22 35 27 30 29 29 32 32 33 26 Ed Balls 22 200 2825251936 26 23 21 23 21 24 22 23 21 20 23 23 Andy Burnham 19 14 17 0 21 24 14 18 19 21 18 19 19 19 18 18 20 21 20 16 David Miliband 17 13 20 30 0 35 13 12 24 10 27 13 21 16 20 17 17 15 12 23 Diane Abbott 11 0 15 8 11 16 11 2 7 12 12 9 12 11 11 12 10 12 11 12 Weighted Sample 905 90 74 75 351 285 82 40 56 233 203 431 474 299 319 519 387 303 267 336 Unweighted Sample 914 87 78 84 341 293 79 40 60 228 214 429 485 290 334 592 322 283 280 351 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% Miliband preference - September [Excluding definitely wouldn't vote] David Miliband 48 19 28 41 100 1 25 34 37 86 17 100 0 80 17 47 49 48 46 48 Ed Miliband 52 81 72 59 0 99 75 66 63 14 83 0 100 20 83 53 51 52 54 52 1 © 2010 YouGov plc. -

Core Group Core Group Plus Neutral but Not Hostile

CORE GROUP NEUTRAL BUT CORE GROUP HOSTILE CORE GROUP PLUS NOT HOSTILE NEGATIVE GROUP Andy Alan Andy Slaughter Alan Whitehead Alan Johnon McDonald Campbell Catherine Alison Angela Rayner Adrian Bailey Alan Meale Smith McGovern Dennis Alex Andrew Gwynne Angela Smith Ann Coffey Skinner Cunningham Barry Diane Abbott Albert Owen Andy Burnham Anna Turley Sheerman Grahame Catherine West Andrew Smith Ed Miliband Caroline Flint Morris Margaret Ian Lavery Angela Eagle Ben Bradshaw Chris Evans Greenwood Bridget Ian Mearns Carolyn Harris Ann Clwyd Chris Leslie Phillipson Imran Chinyelu Chuka Barbara Keeley Diana Johnson Hussain Onwurah Umunna Jeremy Daniel Elizabeth Christina Rees Barry Gardiner Corbyn Zeichner Kendall John Emma Dave Anderson Bill Esterson Dan Jarvis McDonnell Reynolds Catherin Fiona Jon Trickett Dawn Butler Derek Twigg McKinnell Mactaggart Graham Kate Osamor David Winnick Chris Bryant Frank Field Jones Kelvin Debbie Gareth Harriet Chris Matheson Hopkins Abrahams Thomas Harman RIP Michael Emily George Clive Betts Ian Austin Meacher Thornberry Howarth Rebecca Emma Lewell- Geoffrey Clive Efford Ivan Lewis Long-Bailer Buck Robinson Ronnie Gloria de Vicky Foxcroft Colleen Fletcher Jamie Reed Campbell Piero Richard John Harry Harpham David Crausby Graham Allen Burgon Woodcock Luciana Clive Lewis Helen Goodman David Hanson Hilary Benn Berger Rachael Holly Lynch Derek Twigg Ian Murray Margaret Maskell Hodge Ian Lucas Gavin Shuker Jo Cox Mark Tami Jenny Jo Stevens Geraint Davies Mary Creagh Chapman Kate Hollern Gerald Jones Joan Ryan Melanie -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Women Mps in Westminster Photographs Taken May 21St, June 3Rd, June 4Th, 2008

“The House of Commons Works of Art Collection documents significant moments in Parliamentary history. We are delighted to have added this unique photographic record of women MPs of today, to mark the 90th anniversary of women first being able to take their seats in this House” – Hugo Swire, Chairman, The Speaker's Advisory Committee on Works of Art. “The day the Carlton Club accepted women” – 90 years after women first got the vote aim to ensure that a more enduring image of On May 21st 2008 over half of all women women's participation in the political process Members of Parliament in Westminster survives. gathered party by party to have group photographs taken to mark the anniversary of Each party gave its permission for the 90 years since women first got the vote (in photographs to be taken. For the Labour February 1918 women over 30 were first Party, Barbara Follett MP, the then Deputy granted the vote). Minister for Women and Equality, and Barbara Keeley MP, who was Chair of the Labour Party Women’s Committee and The four new composite Caroline Adams, who works for the photographs taken party by Parliamentary Labour Party helped ensure that all but 12 of the Labour women party aim to ensure that a attended. more enduring image of For the Conservative women's participation in the Party, The Shadow Leader of the House of political process survives Commons and Shadow Minister for Until now the most often used photographic Women, Theresa May image of women MPs had been the so called MP and the Chairman “Blair Babes” picture taken on 7th May 1997 of the Conservative shortly after 101 Labour women were elected Party, Caroline to Westminster as a result of positive action by Spelman MP, enlisted the Labour Party. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

New Ministerial Team at the Department of Health

New Ministerial Team at the Department of Health The Rt Hon Alan Johnson MP Secretary of State for Health Alan Johnson was first elected to Parliament in 1997 as the Member for Kingston upon Hull. A former postman, Alan Johnson served as a former General Secretary of the Communication Workers Union (CWU) and is one of the largest trade union names to have entered Parliament in recent decades. Often credited with the much coveted tag of being an "ordinary bloke", he is highly articulate and effective and is credited with the successful campaign that deterred the previous Conservative government from privatising the Post Office. Popular among his peers, Alan Johnson is generally regarded to be on the centre right of the Labour Party and is well regarded by the Labour leadership. As a union member of Labour's ruling NEC (up to 1996) he was seen as supportive of Tony Blair's attempts to modernise the Labour Party. He was the only senior union leader to back the abolition of Labour's clause IV. He becomes the first former union leader to become a cabinet minister in nearly 40 years when he is appointed to the Work and Pensions brief in 2004. After moving to Trade and Industry, he becomes Education and Skills Secretary in May 2006. After being tipped by many as the front-runner in the Labour deputy leadership contest of 2007, Alan Johnson was narrowly beaten by Harriet Harman. Commons Career PPS to Dawn Primarolo: as Financial Secretary, HM Treasury 1997-99, as Paymaster General, HM Treasury 1999; Department of Trade and Industry 1999-2003: