Juvenile-Onset Immunodeficiency Secondary to Anti-Interferon-Gamma Autoantibodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case for Diagnosis* Caso Para Diagnóstico*

RevABDV81N5.qxd 09.11.06 09:42 Page 490 490 Qual o seu diagnóstico? Caso para diagnóstico* Case for diagnosis* Rodrigo Pereira Duquia1 Hiram Larangeira de Almeida Jr2 Ernani Siegmann Duvelius3 Manfred Wolter4 HISTÓRIA DA DOENÇA Paciente do sexo feminino, de 76 anos, há lesões liquenóides dorsais, solicitação do teste de dois anos apresentou linfadenopatias na região Mantoux e exames laboratoriais, com a suspeita de cervical (Figura 1) e axilar esquerda. Após um ano scrofuloderma e líquen scrofulosorum. Nessa oca- iniciou fistulização e drenagem de material esbran- sião a paciente apresentava-se em mau estado geral quiçado das lesões, emagrecimento e aparecimen- com febre persistente, emagrecimento importante to de lesões anulares liquenóides com centro atró- e astenia. fico na região dorsal (Figura 2), levemente prurigi- O Mantoux foi fortemente reator, 24mm, velo- nosas. Há seis meses realizou biópsia da região cer- cidade de sedimentação globular de 96mm, a cultura vical, que foi inconclusiva. Posteriormente foi enca- da secreção cervical foi negativa, e PCR foi positiva minhada para avaliação dermatológica, sendo reali- para Mycobacterium tuberculosis. zada coleta de material da região cervical, enviado O exame histopatológico das lesões do dorso então para cultura e reação em cadeia pela polime- revelou espongiose focal na epiderme com alguns rase (PCR). Além disso, realizaram-se biópsia das queratinócitos necróticos, apresentando na derme FIGURA 1: Lesões eritematosas com crosta hemática recobrindo as FIGURA 2: Lesões liquenóides, anulares, com atrofia central na fístulas na região cervical esquerda região dorsal. No detalhe à direita, a atrofia central e os bordos papulosos e anulares ficam mais evidentes Recebido em 22.02.2006. -

A Rare Case of Tuberculosis Cutis Colliquative

Jemds.com Case Report A Rare Case of Tuberculosis Cutis Colliquative 1 2 3 4 5 Shravya Rimmalapudi , Amruta D. Morey , Bhushan Madke , Adarsh Lata Singh , Sugat Jawade 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, India. INTRODUCTION Tuberculosis is one of the oldest documented diseases known to mankind and has Corresponding Author: evolved along with humans for several million years. It is still a major burden globally Dr. Bhushan Madke, despite the advancement in control measures and reduction in new cases1 Professor and Head, Tuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease. It is caused by Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an acid-fast bacillus with inhalation of airborne droplets Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, 2,3 being the route of spread. The organs most commonly affected include lungs, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical intestines, lymph nodes, skin, meninges, liver, oral cavity, kidneys and bones.1 About Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, India. 1.5 % of tuberculous manifestations are cutaneous and accounts for 0.1 – 0.9 % of E-mail: [email protected] total dermatological out patients in India.2 Scrofuloderma is a type of cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) which is a rare presentation in dermatological setting and is DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2021/67 difficult to diagnose. It was earlier known as tuberculosis cutis colliquative develops as an extension of infection into the skin from an underlying focus, usually the lymph How to Cite This Article: Rimmalapudi S, Morey AD, Madke B, et al. A nodes and sometimes bone. -

Delayed Granulomatous Lesion at the Bacillus Calmette-Gue´Rin Vaccination Site

302 Letters to the Editor baseline warts (imiquimod 11% vs. vehicle 6%; p = 0.488), 2. Buetner KR, Spruance SL, Hougham AJ, Fox TL, Owens ML, more imiquimod-treated patients experienced a 50% reduc- Douglas JM Jr. Treatment of genital warts with an immune- tion in baseline wart area (38% vs. 14%; p = 0.013). Use of response modi er (imiquimod). J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 32: imiquimod was not associated with any changes in laboratory 230–239. values, including CD4 count. It was not associated with any 3. Beutner KR, Tyring SK, Trofatter KF, Douglas JM, Spruance S, adverse drug-related events, and no exacerbation of HIV/AIDS Owens ML, et al. Imiquimod, a patient-applied immune-response was attributed to the use of imiquimod. However, it appeared modi er for treatment of external genital warts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 789–794. that topical imiquimod was still less eVective at achieving total 4. Tyring SK, Arany I, Stanley MA, Tomai MA, Miller RL, clearance than in the studies with HIV-negative patients, which Smith MH, et al. A randomized, controlled, molecular study of is most likely a re ection of the impaired cell-mediated condylomata acuminata clearance during treatment with imiqui- immunity seen in the HIV-positive population (8). mod. J Infect Dis 1998; 178: 551–555. There has also been a report of improved success when topical 5. Arany I, Tyring SK, Stanley MA, Tomai MA, Miller RL, imiquimod was combined with more traditional destructive Smith MH, et al. Enhancement of the innate and cellular immune therapy for HPV infection in HIV-positive patients, particularly response in patients with genital warts treated with topical imiqui- in the setting of the use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy mod cream 5%. -

Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis Presenting As an Annular Hyperkeratotic Plaque

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis Presenting as an Annular Hyperkeratotic Plaque Shahbaz A. Janjua, MD; Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS; Sabrina Guillen, MD GOAL To understand cutaneous tuberculosis to better manage patients with the condition OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Recognize the morphologic features of cutaneous tuberculosis. 2. Describe the histopathologic characteristics of cutaneous tuberculosis. 3. Explain the treatment options for cutaneous tuberculosis. CME Test on page 320. This article has been peer reviewed and approved Einstein College of Medicine is accredited by by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of Medicine, the ACCME to provide continuing medical edu- Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Review date: cation for physicians. October 2006. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates This activity has been planned and imple- this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA mented in accordance with the Essential Areas PRA Category 1 CreditTM. Physicians should only and Policies of the Accreditation Council for claim credit commensurate with the extent of their Continuing Medical Education through the participation in the activity. joint sponsorship of Albert Einstein College of This activity has been planned and produced in Medicine and Quadrant HealthCom, Inc. Albert accordance with ACCME Essentials. Drs. Janjua, Khachemoune, and Guillen report no conflict of interest. The authors discuss off-label use of ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and rifampicin. Dr. Fisher reports no conflict of interest. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TVC) is a form evolving cell-mediated immunity. TVC usually of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from acci- begins as a solitary papulonodule following a dental inoculation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis trivial injury or trauma on one of the extremi- in a previously infected or sensitized individ- ties that soon acquires a scaly and verrucous ual with a moderate to high degree of slowly surface. -

86A1bedb377096cf412d7e5f593

Contents Gray..................................................................................... Section: Introduction and Diagnosis 1 Introduction to Skin Biology ̈ 1 2 Dermatologic Diagnosis ̈ 16 3 Other Diagnostic Methods ̈ 39 .....................................................................................Blue Section: Dermatologic Diseases 4 Viral Diseases ̈ 53 5 Bacterial Diseases ̈ 73 6 Fungal Diseases ̈ 106 7 Other Infectious Diseases ̈ 122 8 Sexually Transmitted Diseases ̈ 134 9 HIV Infection and AIDS ̈ 155 10 Allergic Diseases ̈ 166 11 Drug Reactions ̈ 179 12 Dermatitis ̈ 190 13 Collagen–Vascular Disorders ̈ 203 14 Autoimmune Bullous Diseases ̈ 229 15 Purpura and Vasculitis ̈ 245 16 Papulosquamous Disorders ̈ 262 17 Granulomatous and Necrobiotic Disorders ̈ 290 18 Dermatoses Caused by Physical and Chemical Agents ̈ 295 19 Metabolic Diseases ̈ 310 20 Pruritus and Prurigo ̈ 328 21 Genodermatoses ̈ 332 22 Disorders of Pigmentation ̈ 371 23 Melanocytic Tumors ̈ 384 24 Cysts and Epidermal Tumors ̈ 407 25 Adnexal Tumors ̈ 424 26 Soft Tissue Tumors ̈ 438 27 Other Cutaneous Tumors ̈ 465 28 Cutaneous Lymphomas and Leukemia ̈ 471 29 Paraneoplastic Disorders ̈ 485 30 Diseases of the Lips and Oral Mucosa ̈ 489 31 Diseases of the Hairs and Scalp ̈ 495 32 Diseases of the Nails ̈ 518 33 Disorders of Sweat Glands ̈ 528 34 Diseases of Sebaceous Glands ̈ 530 35 Diseases of Subcutaneous Fat ̈ 538 36 Anogenital Diseases ̈ 543 37 Phlebology ̈ 552 38 Occupational Dermatoses ̈ 565 39 Skin Diseases in Different Age Groups ̈ 569 40 Psychodermatology -

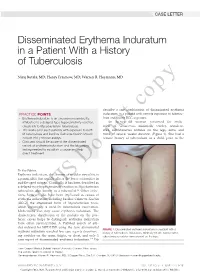

Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient with a History of Tuberculosis

CASE LETTER Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient With a History of Tuberculosis Niraj Butala, MD; Henry Fraimow, MD; Warren R. Heymann, MD copy describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema PRACTICE POINTS induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tubercu- • Erythema induratum is an uncommon panniculitis losis and recent BCG exposure. attributed to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, An 88-year-old woman presented for evalu- classically to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcer- • The workup for such patients with exposure to both ated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and M tuberculosis and bacillus Calmette-Guérin should trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a include IFN-γ release assays. remotenot history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the • Clinicians should be aware of the disseminated variant of erythema induratum and the laboratory testing needed to establish a cause and help direct treatment. Do To the Editor: Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infec- tions, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristicCUTIS distribution of the nodules on the pos- terior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of arti- cles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated FIGURE 1. -

Update on Cutaneous Tuberculosis*

Revista6Vol89ingles_Layout 1 10/10/14 11:08 AM Página 925 REVIEW 925 s Update on cutaneous tuberculosis* Maria Fernanda Reis Gavazzoni Dias1 Fred Bernardes Filho1 Maria Victória Quaresma1 Leninha Valério do Nascimento2 José Augusto da Costa Nery3 David Rubem Azulay1,4 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142998 Abstract: Tuberculosis continues to draw special attention from health care professionals and society in general. Cutaneous tuberculosis is an infection caused by M. tuberculosis complex, M. bovis and bacillus Calmette- Guérin. Depending on individual immunity, environmental factors and the type of inoculum, it may present var- ied clinical and evolutionary aspects. Patients with HIV and those using immunobiological drugs are more prone to infection, which is a great concern in centers where the disease is considered endemic. This paper aims to review the current situation of cutaneous tuberculosis in light of this new scenario, highlighting the emergence of new and more specific methods of diagnosis, and the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate the par- asite-host interaction. Keywords: Erythema Induratum; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Tuberculosis; Tuberculosis, Cutaneous INTRODUCTION Tuberculosis (TB) continues to draw special worsening of cutaneous tuberculosis and the emer- attention from health care professionals and society as gence of subclinical infections. The most common a whole. It still meets all the criteria for prioritization clinical presentations of infection by Mycobacterium of a public health disorder, i.e. large magnitude, vul- tuberculosis-associated IRIS are lymphadenitis or lym- nerability and transcendence.1 Cutaneous tuberculosis phadenopathy.7-9 is an infection caused by M. tuberculosis complex, M. Knowledge about TB infection and its clinical bovis and bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), which management were outside the scope of most dermato- depending on individual immunity, environmental logical practices. -

Original Article Cutaneous Manifestations of Extra Pulmonary

Original Article Cutaneous Manifestations of Extra pulmonary Tuberculosis Ahmad S1, Ahmed N2, Singha JL3, Mamun MAA4, Hassan ASMFU5, Aziz NMSB6, Alam SI7 Conflict of Interest: None Abstract: Received: 12-08-2018 Background: Ulcers and surgical wounds not healing well and expectedly are common problems Accepted: 06-11-2018 www.banglajol.info/index.php/JSSMC among patients in countries like us. Ulcers may develop spontaneously or following a penetrating injury. wounds not healing well are common among poor, lower middle class and middle class people. Postsurgical non-healing wound or chronic discharging sinuses at the scar site are also common in that class of people. Suspecting malignancy or tuberculosis in these types of wounds we have sent wedge or excision biopsy for these ulcers in about 500 cases and found tuberculosis in 65 cases. In rest of the cases histopathology reports found as non- specific ulcers, Malignant melanoma, squamous or basal cell carcinoma, Verruca vulgaris. Objectives: To find out the relationship of tuberculosis with chronic or nonhealing ulcers. Methods: This is a prospective observational study conducted for patients coming to our chambers, OPD of a district general hospital and Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital, Dhaka from July 2012 to June 2018. Results: Mean age of the study subjects were 28±2. Among the study subjects nonspecific ulcer or sinus tracts were found in 418 (83.6%), tuberculosis in 65 (13%), Malignant melanoma 7 (1.4%), Verruca vulgaris 5(1%), squamous cell carcinoma 3(0.6), basal cell carcinoma 2 (0.4%). Biopsy done only for very suspicious ulcers or wounds. Key Words: Cutaneous Conclusion: With this very small sample size it is difficult to conclude regarding incidence of manifestation, Extrapulmonary cutaneous involvement of extra pulmonary tuberculosis , but every clinician should think of it in case involvement, Tuberculosis. -

Ulcers of the Face and Neck in a Woman with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Presentation of a Clinical Case

CLINICAL CASE REPORT Ulcers of the face and neck in a woman with pulmonary tuberculosis: presentation of a clinical case A Morrone, F Dassoni, MC Pajno, R Marrone, R Calcaterra, G Franco, E Maiani National Institute for Health Migration and Poverty, Rome, Italy Submitted: 30 March 2010; Revised: 12 August 2010; Published: 4 October 2010 Morrone A, Dassoni F, Pajno MC, Marrone R, Calcaterra R, Franco G, Maiani E Ulcers of the face and neck in a woman with pulmonary tuberculosis: presentation of a clinical case Rural and Remote Health 10: 1485. (Online), 2010 Available from: http://www.rrh.org.au A B S T R A C T Introduction: Tuberculosis (TB), which is endemic in developing countries, is an important public health problem. Cutaneous TB (CT) represents 1.5% of all TB cases and is considered to be a re-emerging pathology in developing countries due to co-infections with HIV, multidrug-resistant TB, a shortage of health facilities with appropriate diagnostic equipment, reduced access to treatment, and poor treatment compliance among patients who often resort to traditional medicine. Case report: This report describes the case of a 70 year-old woman who attended the outpatients department of the Italian Dermatological Centre (IDC) in Mekelle, the capital city of Tigray (Northern Ethiopia), complaining of the appearance of two ulcers on her face and neck. The patient had a history of pulmonary TB, with her initial systemic treatment ceased after 1 month. Cytological examination of a needle aspiration from the neck lesion showed a non-specific bacterial superinfection. No acid-fast bacilli were found on Ziehl-Nielsen staining. -

Boards Fodder Vaccines in Dermatology by Caroline A

boards fodder Vaccines in dermatology By Caroline A. Nelson, MD LIVE INACTIVATED/KILLED TOXOID SUBUNIT/ CONJUGATE Adenovirus Hepatitis A virus Diphtheria, tetanus, and Anthrax Cholera (oral) Influenza (injection) pertussis Haemophilus influenzae Influenza (intranasal) Japanese encephalitis Hepatitis B virus Measles, mumps, rubella Polio (injection) Human papillomavirus Polio (oral) Rabies Influenza (injection) Rotavirus Meningococcus Smallpox Pneumococcus Tuberculosis Typhoid (injection) Typhoid (oral) Zoster (Shingrix) Varicella zoster virus Yellow fever Zoster (Zostavax) VACCINE ROUTINE INDICATIONS SKIN REACTIONS/ COMPLICATIONS* NOTES† Viral Infections Hepatitis B Infants at 0-, 2-, and 6-months of Anetoderma, granuloma annulare, lichen Patients without evidence of disease or immunity virus (HBV) age and at-risk adults planus, lichen nitidus, lichen striatus, on serologic testing and with risk factors should papular acrodermatitis of childhood be offered vaccination prior to immunosuppression (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome), polyarteritis nodosa, and pseudolymphoma Human papil- Gardasil and Gardasil-9: Patients Localized lipoatrophy Vaccines contain L1 capsid protein of specific HPV lomavirus 9-26 years of age with a second types: Cervarix has 16 and 18; Gardasil has 6, 11, (HPV) dose after 6-12 months (patients 16, and 18; and Gardasil-9 has 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 15-26 years of age should receive 45, 52, and 58 a second dose after 1-2 months and a third dose after 6 months) Can be administered regardless of history of abnor- mal PAP smear -

Lichen Scrofulosorum: an Uncommon Manifestation of a Common Disease

[Downloaded free from http://www.ijmyco.org on Thursday, September 24, 2020, IP: 62.193.78.199] Case Report Lichen scrofulosorum: An Uncommon Manifestation of a Common Disease Nirmal Chand Kajal1, P. Prasanth1, Ritu Dadra1 1Department of Chest and TB, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India Abstract Tuberculid is a cutaneous immunologic reaction to the presence of tuberculosis (TB), which is often occult, elsewhere in the body or their fragments released from a different site of manifest or past tuberculous infection. These eruptive lesions are due to hematogenous dissemination of bacilli in a host with a high degree of immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Although rare, these specific lesions are important diagnostic markers of TB. Lichen scrofulosorum (LS) is one of the recognized tuberculids, usually seen in children and young adults. We report a female who was diagnosed with LS and was treated appropriately. This case report highlights the uncommon, easily misdiagnosed but readily treatable case of LS and emphasizes its early diagnosis, detection, and treatment of otherwise an occult systemic TB in young patients. Keywords: Biopsy, cutaneous tuberculosis, hypersensitivity, tuberculid Submitted: 04‑Mar‑2020 Revised: 06‑Apr‑2020 Accepted: 14‑Apr‑2020 Published: 28‑Aug‑2020 INTRODUCTION they are important disorders in developing nations, where 95% of all cases of TB occur. A wide range of skin The disease tuberculosis (TB) is perhaps as old as humankind, disorders have been interpreted as tuberculids in the past. with evidence of the disease being found in the vertebrae However, currently, only three entities are regarded as true of the Neolithic man in Europe and Egyptian mummies. -

Disseminated Cutaneous BCG Infection Following BCG Immunotherapy in Patients with Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepr Rev (2015) 86, 180–185 CASE REPORT Disseminated cutaneous BCG infection following BCG immunotherapy in patients with lepromatous leprosy GEETI KHULLAR*, TARUN NARANG*, KUSUM SHARMA**, UMA NAHAR SAIKIA*** & SUNIL DOGRA* *Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh – 160012, India **Department of Medical Microbiology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh – 160012, India ***Department of Histopathology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh – 160012, India Accepted for publication 19 May 2015 Summary Cutaneous complications of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, especially in the form of generalised disease, are uncommon and mostly occur in immunocompromised individuals. There is a paucity of data on the cutaneous adverse reactions secondary to BCG immunotherapy in leprosy. We report two unique cases of disseminated cutaneous BCG infection following immunotherapy in patients with lepromatous leprosy. To our knowledge, cutaneous BCG infection presenting as widespread lesions after immunotherapy and confirmed by isolation of Mycobacter- ium bovis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has not been described. A high index of suspicion is required when leprosy patients who receive BCG immunotherapy develop new lesions that cannot be classified as either reaction or relapse, and diagnosis may be confirmed on histopathology and PCR. Introduction Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), a live attenuated vaccine