Download When Needing to See a Doctor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Student Study Abroad Survival Guide University of Rhode Island Japanese International Engineering Program

A Student Study Abroad Survival Guide University of Rhode Island Japanese International Engineering Program Table of Contents Pre-Departure Preparation……………………………………………………………2-6 Academic Year …………………………………………………………………. 2 Course Requirements………………………………………………………….. 2 Timeline for Preparing for your Year Abroad ……………………………… 2 Scholarships ………………………………………………………………….... 2 Additional Japanese Language Study Opportunities………..……………… 3 Visa Process……………………………………………….…………………….3 Summer ………………………………………………………………………...4 Travel……………….………………………………………………….. 4 Packing ………………………………………………………………… 5 Banking and Money ………………………………………………….. 6 Year Abroad …………………………………………………………………………... 7 Things to do upon arrival …………………………………………………….. 7 Leaving the Airport ………………………………………………….. 7 Establish Residency …………………………………………………… 8 Housing............………………………………………………………… 8 Communication and Cell Phones ……………………………………. 8 Banking ………………………………………………………………... 8 Orientation …………………………………………………………………….. 9 Life in Tokyo ………………………………………………………………….. 9 Transportation ……………………………………………………….. 10 Groceries ……………………………………………………………… 10 Nightlife ………………………………………………………………. 11 Day Trips ……………………………………………………………… 11 Cultural Integration ………………………………………………… 11 Health and Safety Tips…………………………………………... …………...12 Academics ……………………………………………………………………... 12 Internships ...…………………………………………………………………... 13 After Returning ……………………………………………………………………….. 14 Sharing Your Experiences! …………………………………………………... 14 Pre-departure Preparation This Survival Guide has been developed and maintained by students -

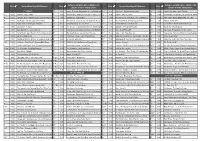

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

A Life Adrift

A Lf A A Life Adrift, the memoir of balladeer-political activist Soeda Azembō (1872- 1944), chronicles his life as one of Japan’s Þ rst modern mass entertainers and imparts an understanding of how ordinary people experienced and accommodated the tumult of life in prewar Japan. Azembō created enka songs sung by tenant farmers in rural hinterlands and factory hands in Tokyo and Osaka. Although his work is still largely unknown outside Japan, his poems and lyrics were so well known at his career’s peak that a single verse served as shorthand expressing popular attitudes about political corruption, sex scandals, spiralling prices, war, and love of motherland. As these categories attest, he embedded in his songs contemporary views on class conß ict, gender relations, and racial attitudes toward international rivals. Ordinary people valued Azembō’s music because it was of them and for them. They also appreciated it for being distinctively modern and home-grown, qualities rare among the cultural innovations that ß ooded into Japan from the mid- nineteenth century. A Life Adrift stands out as the only memoir of its kind, one written Þ rst-hand by a leader in the world of enka singing. The Author Michael Lewis is Professor of History at Michigan State University. 0001a-prelims-Life01a-prelims-Life AAdrift.indddrift.indd i 117/10/087/10/08 11:36:21:36:21 ppmm Routledge Contemporary Japan Series A Japanese Company in Crisis Political Reform in Japan Ideology, strategy, and narrative Leadership looming large Fiona Graham Alisa Gaunder Japan’s Foreign Aid Civil Society and the Internet in Japan Old continuities and new directions Isa Ducke Edited by David Arase Japan’s Contested War Memories Japanese Apologies for World War II The ‘memory rifts’ in historical A rhetorical study consciousness of World War II Jane W. -

Dining at Andaz Tokyo Man with a Mission

NOVEMBER 2015 Japan’s number one English language magazine OKINAWA Island Life and Local Color MAN WITH A MISSION Hungry Like the Wolf DINING AT ANDAZ TOKYO Haute Cuisine atop Toranomon ALSO: Revisiting the Heroic Return of Apollo 13, Fall Foliage Guide, Artistic Tokyo, People, Parties, and Places,www.tokyoweekender.com and Much NOVEMBERMore... 2015 ZP_IPTL_Pub_A4_151029_FIX_vcs6 copy.pdf 1 29/10/2015 15:36 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K NOVEMBER 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com ZP_IPTL_Pub_A4_151029_FIX_vcs6 copy.pdf 1 29/10/2015 15:36 NOVEMBER 2015 CONTENTS 26 C OKINAWA SPECIAL M Windows into the world under the waves, Y island cuisine, and music beyond eisa CM MY 16 24 32 CY CMY K DINING AT ANDAZ TOKYO FALL FOLIAGE GUIDE MAN WITH A MISSION A celebration of seasonal food—and Get out and see the autumn leaves before Bow wow wow yippee yo yippee yay: flowers—served at the highest level they make like a tree and... This wolfpack band is on the prowl 6 The Guide 12 Tokyo Motor Show 22 Dominique Ansel Fashion for the encroaching autumn chill These are a few of the concept cars that He brought the cronut to the foodie world, and the perfect cocktail for fall got our engines running but the French chef has more in store 8 Gallery Guide 14 Omega in Orbit 34 Noh Workshops Takashi Murakami brings the massive Apollo 13 Commander James Lovell believes Stepping into Japanese culture through a “500 Arhats” to the Mori Museum mankind should keep its eyes on the stars centuries-old theatrical tradition 10 Kashima Arts 20 RRR Bistro 38 People, Parties, Places For -

Liner Notes: Aesthetics of Capitalism and Resistance in Contemporary

LINER NOTES: AESTHETICS OF CAPITALISM AND RESISTANCE IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE MUSIC A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jillian Marshall December 2018 © 2018, Jillian Marshall LINER NOTES: AESTHETICS OF CAPITALISM AND RESISTANCE IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE MUSIC Jillian Marshall, Ph.D. Cornell University 2018 This dissertation hypothesizes that capitalism can be understood as an aesthetic through an examination and comparison of three music life worlds in contemporary Japan: traditional, popular, and underground. Through ethnographic fieldwork-based immersion in each musical world for nearly four years, the research presented here concludes that capitalism’s alienating aesthetic is naturally counteracted by aesthetics of community-based resistance, which blur and re-organize the generic boundaries typically associated with these three musics. By conceptualizing capitalism -- and socio-economics on whole – as an aesthetic, this dissertation ultimately claims an activist stance, showing by way of these rather dramatic case studies the self-destructive nature of capitalistic enterprise, and its effects on musical styles and performance, as well as community and identity in Japan and beyond. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Prior to undertaking doctoral studies in Musicology at Cornell in 2011, Jillian Marshall studied East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago, where she graduated with double honors. Jillian has also studied with other institutions, notably Princeton University through the Princeton in Beijing Program (PiB, 2007), and Columbia University through the Kyoto Consortium of Japanese Studies at Doshisha University (KCJS, 2012). Her interest in the music of Japan was piqued during her initial two-year tenure in the country, when she worked as a middle school English teacher in a rural fishing village. -

Punk / Dark / Wave / Indie / Alternative Sat, 21

Punk / Dark / Wave / Indie / Alternative www.redmoonrecords.com Artista Titolo ID Formato Etichetta Stampa N°Cat. / Barcode Condition Price Note 'TIL TUESDAY Welcome home 13217 1xLP Epic CBS NL EPC57094 EX+/EX 12,00 € 'TIL TUESDAY What about love 18067 1x12" Epic CBS UK 6501256 EX/EX 8,00 € 20-20s 20-20s 22418 1xCD Astralwerks USA 7242386093424 USED 7,00 € 20-20s Shake/shiver/moan 22419 1xCD TBD records USA 880882170721 USED 7,00 € Cardsleeve 3 COLOURS RED Beautiful day (3 tracks) 8725 1xCDs Creation rec. UK 50175556703083 USED 2,60 € 411 (four one one) This isn't me 16084 1xCD Cargo rec. USA 723248300427 USED 8,00 € 60ft DOLLS Alison's room (4 tracks) 7869 1xCDs Indolent BMG EU 743215668022 USED 2,60 € A CERTAIN RATIO Good together 8872 1xLP A&M Polygram UK 397011-1 EX+/EX 12,90 € A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS (It's not me) 19956 1x7" Jive Zomba GER 6.13928AC EX+/EX 6,00 € talking\Tanglimara A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I ran (Die Krupps 15005 1x12" Cleopatra USA CLP0590-1 SS 10,00 € remix)\Space age love song (KMFDM remix) A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Never again (the 18502 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.14237 EX+/EX 6,00 € dancer)\Living in heaven A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Nightmares \ 16984 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.13801 JIVE33 EX+/EX 6,00 € Rosenmontag A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Transfer affection\I ran 18501 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.13876AC EX+/EX 6,00 € (live vers.) A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Who's that girl? She's got 1989 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.14470AC EX+/EX+ 6,00 € it (vocal+instr.) A SOMETIMES PROMISE / 3 LETTER ENGAGEMENT 30 seconds in the police 5625 1x7"EP Stratagem USA SRC003 EX+/EX 6,00 € Split EP With inserts station ripcords A TESTA BASSA Clone o.g.m. -

Jogakusei: a Cultural Icon of Meiji Japan

Jogakusei: A Cultural Icon of Meiji Japan By C 2017 Yoko Hori Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Languages and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chair: Elaine Gerbert Akiko Takeyama Sanako Mitsugi Date Defended: 18 April 2017 The thesis committee for Yoko Hori certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Jogakusei: A Cultural Icon of Meiji Japan Chair: Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 18 April 2017 ii ABSTRACT The term joshidaisei, female college students, is often associated with an image of modernity, stylishness, and intelligence in contemporary Japan, and media such as TV, fashion magazines, and websites feature them as if they were celebrities. At the same time, intellectuals criticize joshidaisei for focusing too much on their appearance and leading an extravagant lifestyle. In the chapter, “Branded: Bad Girls Go Shopping” in the book Bad Girls of Japan, Jan Bardsley and Hiroko Hirakawa assert that male intellectuals have criticized the consumer culture of young single woman, which joshidaisei has been a major part of, as a cause of the destruction of the “good wives, wise mothers” ideal, which many people still consider to be the ideal for young women in Japan.1 I argue that educated young women have been a subject of adoration and criticism since the Meiji period when Japanese government started to promote women’s education as a part of the modernization and westernization process of Japan. It was also the time when people started to use the term “good wives, wise mothers” to promote an ideal image of women who could contribute to the advancement of the country. -

Germany in Japan

Since 1970 FREE Vol.41 No.18 Oct 1st - Oct 15, 2010 www.weekenderjapan.com Including Japan’s largest online classifieds Germany in Japan A 150 year-old-relationship that began in Yokohama Plus: The Forests of Aśoka at the Hara Oktoberfest! and Bill Hersey’s Parties People & Places CONTENTS Volume 41 Number 18 Oct 1st - Oct 15th, 2010 4 Executive Profiles: Trevor Reynolds 5 The View From Here 6-7 Tokyo Happenings 9 Arts and Entertainment 10-11 Tokyo Tables 12-16 Feature: Yokohama 19-21 Weekender Interview: Terrence Parker 22-25 Parties, People & Places 26-27 London Calling Event 28-29 Products: Designed in Deutschland 30-31 Real Estate 32-33 Classifieds 34 Back in the Day: Sumo comes to Germany CONTRIBUTORS Christopher Jones, Thomas PUBLISHER Ray Pedersen Fukuyama, Ian de Stains OBE, EDITOR Ray Pedersen ASSISTANT EDITOR Stephen Parker Cover and inside photo courtesy of: Library of Congress MEDIA MANAGER Tomas Castro MEDIA CONSULTANTS Mary Rudow, Pia von Waldau EST. Corky Alexander and Susan Scully, 1970 RESEARCHER Rene Angelo Pascua OFFICE Weekender Magazine, 5th floor, Regency Shinsaka Building, CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Owen Schaefer (Arts), Bill Hersey 8-5-8 Akasaka, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-0052 (Society), Elisabeth Lambert (Health & Eco), Darrell Nelson Tel. 03-6846-5615 Fax: 03-6846-5616 (Sustainable Business) Email: [email protected] Opinions expressed by Weekender contributors are not necessarily www.weekenderjapan.com those of the publisher. 3 WEEKENDER B u s i n e s s C-Level Profiles / Executives in Japan Photo courtesy of Australia Society of Australia courtesy Photo EdwardTrevor Reynolds Suzuki President of the Australia Society Tokyo A 20 year resident of Japan, Trevor Reynolds has many hats: father, money manager and president of the Australian Society of Japan. -

Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey: Araki Nobuyoshi’S

SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY/WINTER JOURNEY: ARAKI NOBUYOSHI’S CONTEMPORARY SHISHŌSETSU by ANNE CHRISTINE TAYLOR A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anne Christine Taylor Title: Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey: Araki Nobuyoshi’s Contemporary Shishōsetsu This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Akiko Walley Chairperson Joyce Cheng Member Sherwin Simmons Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Anne Christine Taylor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Anne Christine Taylor Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2013 Title: Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey: Araki Nobuyoshi’s Contemporary Shishōsetsu Senchimentaru na tabi fuyu no tabi or Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey, a photobook created and published by photographer Araki Nobuyoshi in 1991, documented two highly personal events of the photographer’s life. The first section consists of twenty- two images of Araki’s 1971 honeymoon with his wife Yōko Aoki, while the second section features ninety-one images and an essay documenting the last six months of Yōko’s life in 1989-90. This thesis measures SJ/WJ against a Japanese literary tradition invoked by Araki in his opening manifesto: the shishōsetsu. -

The Otaku Lifestyle: Examining Soundtracks in the Anime Canon

THE OTAKU LIFESTYLE: EXAMINING SOUNDTRACKS IN THE ANIME CANON A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by MICHELLE JURKIEWICZ B.M., University of Central Missouri, 2014 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 MICHELLE JURKIEWICZ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE OTAKU LIFESTYLE: EXAMINING SOUNDTRACKS IN THE ANIME CANON Michelle Jurkiewicz, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, or anime, has been popular around the globe for the last sixty years. Anime has its own fan culture in the United States known as otaku, or the obsessive lifestyle surrounding manga and anime, which has resulted in American production companies creating their own “anime.” Japanese filmmakers do not regard anime simply as a cartoon, but instead realize it as genre of film, such as action or comedy. However, Japanese anime is not only dynamic and influential because of its storylines, characters, and themes, but also for its purposeful choices in music. Since the first anime Astro Boy and through films such as Akira, Japanese animation companies combine their history from the past century with modern or “westernized” music. Unlike cartoon films produced by Disney or Pixar, Japanese anime do not use music to mimic the actions on-screen; instead, music heightens and deepens the plot and emotions. This concept is practiced in live-action feature films, and although anime consists of hand-drawn and computer-generated cartoons, Japanese directors and animators create a “film” experience with their dramatic choice of music. -

Japan Assemblage Mp3, Flac, Wma

Japan Assemblage mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Assemblage Country: UK & Ireland Released: 2004 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1304 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1161 mb WMA version RAR size: 1901 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 905 Other Formats: MP4 AHX AA TTA MMF VQF AUD Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Adolescent Sex 4:16 2 Stateline 4:48 3 Communist China 2:44 4 . Rhodesia 6:49 5 Suburban Berlin 5:01 Life In Tokyo 6 Music By, Lyrics By – David Sylvian, Giorgio MoroderProducer – Giorgio 3:34 Moroder 7 European Son 3:42 All Tomorrows Parties 8 Co-producer – Japan, Simon Napier-BellEngineer – Keith BesseyWritten-By – 4:15 Lou Reed 9 Quiet Life 4:52 I Second That Emotion 10 Engineer – Nigel WalkerMusic By, Lyrics By – Al Cleveland, Smokey 3:47 RobinsonProducer – John Punter Bonus Tracks European Son (John Punter 12" Mix) 11 5:04 Remix – John Punter I Second That Emotion (12" Version) 12 5:19 Remix – John Punter Life In Tokyo Part II (Special Remix) 13 4:06 Music By, Lyrics By – David Sylvian, Giorgio MoroderRemix – Giorgio Moroder Life In Tokyo (1982 Version) 14 Music By, Lyrics By – David Sylvian, Giorgio MoroderProducer – Giorgio 7:07 Moroder Bonus Videos Video1 I Second That Emotion 3:39 Video2 Life In Tokyo 3:31 Companies, etc. Distributed By – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Manufactured By – Deluxe Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Copyright (c) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Credits Art Direction [Original Art Direction] – David Shortt Artwork [Sleeve Restoration And Artwork By] – Cally Bass Guitar, Saxophone, -

WEST of JAPAN Ice? in This Day and Age? JAPAN 'I Don't Really Like II"

24 Record Mirror, Jahuary 5.1980 / JAPAN's David Sylvian: "I don't like dry Ice." WEST OF JAPAN ice? In this day and age? JAPAN 'I don't really like II". Sylvian told me later "I didn't Ryerson Theatre, know we were going to use it again, and we won't from Toronto now on. We had it when we played in Los Angeles and no-one saw us for the !UM three numbers Bul l like the DECEMBER HIFI FOR PLEASURE JAPAN Is not a rock 'n' roll band. You can't dance to smoke, we use it to emphasise the lights " music, sing to their songs. They their you can't along I asked Min it the band weren't making things dif- are not the kind of band you could work up a sweat ficult for themselves by using effects like that - and listening to So how come 1400 people In this the make up which out with the end of glam rock. polytechnic roared, applauded and stamped their feet - "I don't see It at a 1974 image," in appreciation of Japan's performance? answered David "I the tact that they're popular here is in no doubt The don't think we're glare rock. I'd wear make up anyway I'd be if I 11 fact that they're extremely popular in Japan (the coun. compromising didn't wear now. because I m £2,000 I try) Is hardly surprising. Japanese girls love the trail -doing what think I should do have strong principles and I looking bands, the boys who look as II all won't change them for anybody There's no point they spend in their daylight hours under a rock They aren't at all pre- being successful unless you are on your own terms 01 judlced (as we and the Americans are) in their view of "A tol what we do Is tongue In cheek There's a lot wear of men who make up offstage as well as on humour in what I write Sonie things lust aren't worth of Agfa But Canadians, the lumberjacks of the northern meant to be taken seriously " hemisphere.