Early Co-Operatives in Sheffield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Registers of General Admission South Yorkshire Lunatic Asylum (Later Middlewood Hospital), 1872 - 1910 : Surnames L-R

Index to Registers of General Admission South Yorkshire Lunatic Asylum (Later Middlewood Hospital), 1872 - 1910 : Surnames L-R To order a copy of an entry (which will include more information than is in this index) please complete an order form (www.sheffield.gov.uk/libraries/archives‐and‐local‐studies/copying‐ services) and send with a sterling cheque for £8.00. Please quote the name of the patient, their number and the reference number. Surname First names Date of admission Age Occupation Abode Cause of insanity Date of discharge, death, etc No. Ref No. Laceby John 01 July 1879 39 None Killingholme Weak intellect 08 February 1882 1257 NHS3/5/1/3 Lacey James 23 July 1901 26 Labourer Handsworth Epilepsy 07 November 1918 5840 NHS3/5/1/14 Lack Frances Emily 06 May 1910 24 Sheffield 30 September 1910 8714 NHS3/5/1/21 Ladlow James 14 February 1894 25 Pit Laborer Barnsley Not known 10 December 1913 4203 NHS3/5/1/10 Laidler Emily 31 December 1879 36 Housewife Sheffield Religion 30 June 1887 1489 NHS3/5/1/3 Laines Sarah 01 July 1879 42 Servant Willingham Not known 07 February 1880 1375 NHS3/5/1/3 Laister Ethel Beatrice 30 September 1910 21 Sheffield 05 July 1911 8827 NHS3/5/1/21 Laister William 18 September 1899 40 Horsekeeper Sheffield Influenza 21 December 1899 5375 NHS3/5/1/13 Laister William 28 March 1905 43 Horse keeper Sheffield Not known 14 June 1905 6732 NHS3/5/1/17 Laister William 28 April 1906 44 Carter Sheffield Not known 03 November 1906 6968 NHS3/5/1/18 Laitner Sarah 04 April 1898 29 Furniture travellers wife Worksop Death of two -

Agenda Item 7G

Agenda Item 7g Case Number 18/02802/FUL (Formerly PP-07138683) Application Type Full Planning Application Proposal Demolition of existing buildings and erection of a Class A1 retail foodstore including car parking, access, landscaping, ball stop netting and supporting structures and sportsfield parking facility (amended plans and description) Location Tudor Gates Unit 1 Parkers Yard Stannington Road Sheffield S6 5FL Date Received 20/07/2018 Team West and North Applicant/Agent GVA Recommendation Grant Conditionally Subject to Legal Agreement Time limit for Commencement of Development 1. The development shall be begun not later than the expiration of three years from the date of this decision. Reason: In order to comply with the requirements of the Town and Country Planning Act. Approved/Refused Plan(s) 2. The development must be carried out in complete accordance with the following approved documents: Site Location Plan - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2200-S4-P4 Existing Site Plan - Foodstore - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2201-S4-P4 Proposed Site Plan - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2202-S4-P17 Building Floor Plan - 7195-SMR-00-GF-DR-A-2301-S4-P4 Site Sections - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2203-S4-P7 External Works Plan - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2204-S4-P10 Cycle Parking and Trolley Bay - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2205-S4-P6 Roof Plan - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2302-S4-P3 Elevations - 7195-SMR-00-XX-DR-A-2303-S4-P5 Landscape Details - R/2103/1N Topographical Survey - D510-001 Page 175 Topographical Survey - D510-002 Highway Markings & Outbound Bus Stop Re-location - 7195-SMR-00-ZZ-DR-A-2211- -

Green Routes - November 2015 Finkle Street Old Denaby Bromley Hoober Bank

Langsett Reservoir Newhill Bow Broom Hingcliff Hill Pilley Green Tankersley Elsecar Roman Terrace Upper Midhope Upper Tankersley SWINTON Underbank Reservoir Midhopestones Green Moor Wortley Lea Brook Swinton Bridge Midhope Reservoir Hunshelf Bank Smithy Moor Green Routes - November 2015 Finkle Street Old Denaby Bromley Hoober Bank Gosling Spring Street Horner House Low Harley Barrow Midhope Moors Piccadilly Barnside Moor Wood Willows Howbrook Harley Knoll Top Cortworth Fenny Common Ings Stocksbridge Hoober Kilnhurst Thorncliffe Park Sugden Clough Spink Hall Wood Royd Wentworth Warren Hood Hill High Green Bracken Moor Howbrook Reservoir Potter Hill East Whitwell Carr Head Whitwell Moor Hollin Busk Sandhill Royd Hooton Roberts Nether Haugh ¯ River Don Calf Carr Allman Well Hill Lane End Bolsterstone Ryecroft Charltonbrook Hesley Wood Dog Kennel Pond Bitholmes Wood B Ewden Village Morley Pond Burncross CHAPELTOWN White Carr la Broomhead Reservoir More Hall Reservoir U c Thorpe Hesley Wharncliffe Chase k p Thrybergh Wigtwizzle b Scholes p Thorpe Common Greasbrough Oaken Clough Wood Seats u e Wingfield Smithy Wood r Brighthorlmlee Wharncliffe Side n Greno Wood Whitley Keppel's Column Parkgate Aldwarke Grenoside V D Redmires Wood a Kimberworth Park Smallfield l o The Wheel l Dropping Well Northfield Dalton Foldrings e n Ecclesfield y Grange Lane Dalton Parva Oughtibridge St Ann's Eastwood Ockley Bottom Oughtibridg e Kimberworth Onesacr e Thorn Hill East Dene Agden Dalton Magna Coldwell Masbrough V Bradgate East Herringthorpe Nether Hey Shiregreen -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009

6088 Core Strategy Cover:A4 Cover & Back Spread 6/3/09 16:04 Page 1 Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009 Sheffield Core Strategy Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted by the City Council on 4th March 2009 Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield City Council Sheffield Core Strategy Core Strategy Availability of this document This document is available on the Council’s website at www.sheffield.gov.uk/sdf If you would like a copy of this document in large print, audio format ,Braille, on computer disk, or in a language other than English,please contact us for this to be arranged: l telephone (0114) 205 3075, or l e-mail [email protected], or l write to: SDF Team Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield Core Strategy INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 Introduction to the Core Strategy 1 What is the Sheffield Development Framework about? 1 What is the Core Strategy? 1 PART 1: CONTEXT, VISION, OBJECTIVES AND SPATIAL STRATEGY Chapter 2 Context and Challenges 5 Sheffield: the story so far 5 Challenges for the Future 6 Other Strategies 9 Chapter 3 Vision and Objectives 13 The Spatial Vision 13 SDF Objectives 14 Chapter 4 Spatial Strategy 23 Introduction 23 Spatial Strategy 23 Overall Settlement Pattern 24 The City Centre 24 The Lower and Upper Don Valley 25 Other Employment Areas in the Main Urban Area 26 Housing Areas 26 Outer Areas 27 Green Corridors and Countryside 27 Transport Routes 28 PART -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

7 7A 8 8A Valid From: 29 January 2017

Bus service(s) 7 7a 8 8a Valid from: 29 January 2017 Areas served Places on the route Crystal Peaks Crystal Peaks Bus Stn Beighton (7, 7a) Sheffield Interchange Woodhouse (7, 7a) The Moor Market Birley (8, 8a) Owlerton Stadium Manor Sheffield Hillsborough Leisure Centre Hillsborough Sheffield Wednesday FC Owlerton Wadsley Bridge Ecclesfield What’s changed Services 7, 8 and 8a - Minor changes will be made to the timetable to improve punctuality. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 7, 7a, 8 and 8a 22/09/2015# Rockingham Greasbrough Chapeltown Scholes Thorpe Hesley Parkgate Munsbrough Grenoside Droppingwell Ecclesfield Ecclesfield, Monteney Rd/ Eastwood Monteney Cres 7 Ecclesfield, Monteney Rd/Wordsworth Av 8 8a Kimberworth Wadsley Bridge, East Dene Penistone Rd North/ Shiregreen Blackburn The Gate Inn Masbrough Clifton Fox Hill Ickles Wadsley Bridge, Halifax Rd/ Wincobank Southey Green Rd Broom Owlerton, Penistone Rd/ Meadowhall Canklow Sheeld Wednesday FC Owlerton, Penistone Rd/ Tinsley Hillsborough Leisure Ctr Whiston Owlerton, Carbrook Brinsworth Penistone Rd/ Owlerton Stadium Sheeld, Commercial St Tinsley Park Sheeld, Interchange Catclie Guilthwaite Broomhill, Darnall Glossop Rd/ Waverley Royal Hallamshire Hosp 7aÍ 8 Treeton 7a Ò 7aÑ 8 Ó Littledale Sheeld, Arundel Gate Handsworth Sheeld, Eyre St/Moor Mkt Fence Manor Top, Woodhouse, Cross St/ City Rd/ Tannery St -

Sheffield "!'Hades

1010 SHEFFIELD "!'HADES. HoTELS, INNS & TAVERNS-CC'ntiriued. Old Bradley 'Veil, Mrs. Sarah Green, Pigeon Cote, Geurge Pearce, 29 Steel st! Monad, John Henry Fletcber,- :Frederick 150 Main road, Darnall, S Holmes, R • ·street & 2 Howard street, R I Old Brown Cow, Alfred Harrison, 3 Plant hotel, George Jones, Watb road. l\<Iontagu Arms; Francis John Law, 1! Radford street, S Mexboro', R High street, Mexborougb., R ! Old Cart & Horses, John 'f. Ca.mpsall, Plough, Hy. Creswick, Low Bradfield, S Mor{leth Arms, Mrs. Mary Eleanorl 2 Wortley rd. Mortomley, High Gm. S Plough, Pat rick Lawlesil, 23 Greasbro' Ren~haw, 108 Upper Alien street, S ·Old Cottage, Thomas Leadbeater, Bole road, R Moseley's Arms, Geo. Baxter,8r-83 West Hill road, S Plough, John Lucas, 28 Broad street, S bar & Paradise street, S Old Crab Tree1 L.enry Moore, 137, Plough, John Roddis, Catcliff-e, R · Mulberry Tavern, George Mower, ~lul- Scotland street, S ·Plough, Jn. Arth. Senior, 20 l\lilner rd.S berry street, S Old Cricket Ground Inn, Char~es Tbos. Ploug-h inn, Samuel Lovell, 288 Sandy- Museum, Mrs. Jane E. l\Ioore, 25 Bent, 371 Darnall road, S gate road, Sandygate, S . Orchard street, S Old Cross Daggers, Fredk. Redfearn, Plumpers, \V m. Hazlehurst, 49Duke st.S Nag's Head, Ernest Ibbotson, H-old- l\'Iarket !Jlacc, Woodhouse, S Plumpers, John Hy. 1\Ieades, 'finsley, S. worth, Lnxley, S Old Cross Scythes, Tom Reeves, Totley,S Pomona, Harold Ernest Haycock. 2Il Nag's Head Hotel, George A. Howard, Old Crown, G-eorge De-xter, Green street, Ecelesall road, S Sheffield road, Dronfield, R GreasbrQugh, R Portobello, William Mosforth, 248 P')rto- Napier, Jn.Richd. -

135 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

135 bus time schedule & line map 135 Rotherham - She∆eld View In Website Mode The 135 bus line (Rotherham - She∆eld) has 8 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Grenoside <-> Hillsborough: 8:42 AM - 10:42 PM (2) Grenoside <-> She∆eld Centre: 7:51 PM - 10:51 PM (3) High Green <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 4:52 AM (4) High Green <-> She∆eld Centre: 4:54 AM - 7:19 AM (5) Hillsborough <-> Grenoside: 9:25 AM - 11:21 PM (6) Rotherham Town Centre <-> She∆eld Centre: 5:12 AM - 6:12 PM (7) She∆eld Centre <-> Grenoside: 5:10 PM - 11:25 PM (8) She∆eld Centre <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 5:40 AM - 5:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 135 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 135 bus arriving. -

Knife Crime Request Date

Date: Sat 11 November 2017 Reference Number: 20171863 FOI Category: Stats – Crime Title: Knife Crime Request Date: Wednesday, 18 October, 2017 Response Date: Saturday, 11 November, 2017 Request Details: Broken down by areas of the city, how many knife crimes and stabbings have taken place in Sheffield in the following time frames: 1 - Previous six months 2 - 2017 3 – 2016 SYP Response: I contacted our Crime Management System (CMS) Administrator for assistance with your request. She provided me with the enclosed data and the following explanation of her search criteria/result caveats: POSSESSION OFFENCES – this is a count of offences recorded under the Home Office Offence class - POSSESSION OF ARTICLE WITH BLADE OR POINT, broken down by the scene of crime area. Where the offence was recorded on the CMS crime register between the following dates in the District SHEFFIELD - 01-JAN-2016 AND 31-DEC-2016 01-JAN-2017 AND 31-OCT-2017 01-JAN-2017 AND 31-MAY-2017 USED – This is a count of offences where a KNIFE (in accordance with the Home Office Knife crime definition) has been recorded as USED, broken down by the Home Office Offence class and the Scene of Crime Area. Where the offence was recorded on the CMS crime register between the following dates in the District SHEFFIELD - 01-JAN-2016 AND 31-DEC-2016 01-JAN-2017 AND 31-OCT-2017 01-JAN-2017 AND 31-MAY-2017 The requester has not been specific regarding offence types, therefore I have included all offences types where a KNIFE was used. I have provided the data broken down by Home Office class. -

765 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

765 bus time schedule & line map 765 Grenoside - Bradƒeld School View In Website Mode The 765 bus line (Grenoside - Bradƒeld School) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Parson Cross <-> Worrall: 7:06 AM (2) Wadsley <-> Worrall: 8:04 AM (3) Worrall <-> Ecclesƒeld: 3:10 PM (4) Worrall <-> Hillsborough: 3:23 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 765 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 765 bus arriving. Direction: Parson Cross <-> Worrall 765 bus Time Schedule 37 stops Parson Cross <-> Worrall Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:06 AM Creswick Lane/School Driveway, Parson Cross Tuesday 7:06 AM Wheel Lane/Creswick Lane, Grenoside Wheel Lane, She∆eld Wednesday 7:06 AM Wheel Lane/Greenfolds Road, Grenoside Thursday 7:06 AM Friday 7:06 AM Penistone Road/Blacksmith Lane, Grenoside Rojean Road, She∆eld Saturday Not Operational Norfolk Hill/Penistone Road, Grenoside Norfolk Hill/The Frostings, Grenoside 765 bus Info Main Street/Norfolk Hill, Grenoside Direction: Parson Cross <-> Worrall Stops: 37 Main Street/Vicarage Road, Grenoside Trip Duration: 42 min Main Street, She∆eld Line Summary: Creswick Lane/School Driveway, Parson Cross, Wheel Lane/Creswick Lane, Main Street/Salt Box Lane, Grenoside Grenoside, Wheel Lane/Greenfolds Road, Grenoside, Penistone Road/Blacksmith Lane, Grenoside, Fox Hill Road/Cowper Avenue, Fox Hill Norfolk Hill/Penistone Road, Grenoside, Norfolk Hill/The Frostings, Grenoside, Main Street/Norfolk Hill, Grenoside, Main Street/Vicarage Road, Fox -

Sheffield Freq Guide.Pdf

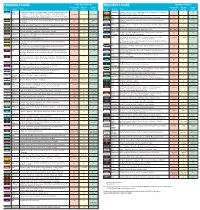

N FREQUENCY (MINUTES) FREQUENCY (MINUTES) 0 100 200 metres M U R 5.20.32 . I R E D FREQUENCY GUIDE FREQUENCY GUIDE L S K 88 R L E C Monday-Friday Saturday Evening/ Monday-Friday Saturday Evening/ Sheffield 0 100 200 yards S RY I CG14 L A W A 6.6a.10 S V Service Operator Route daytime daytime Sunday Service Operator Route daytime daytime Sunday G N T. I IBRA B D 24.25 29 N LTAR City Centre ST 31.31a.57.61.62 R S R R 52.52a S 83.83a E ID ’ E U 1/1a First/ (1) High Green - Chapeltown - Ecclesfield Common - Firth Park - Northern General Hospital - 71/71a/ Stagecoach Sheffield - Manor Top (71, 71a) - Mosborough (71,71a) - Crystal Peaks (72) - Sothall (72) - 60 60 60** E 81.82.85.86 G 56 Y F T E G 97.98 Bus Stops D D Stagecoach Burngreave - Sheffield - Newfield Green - Hemsworth - Jordanthorpe/Batemoor 72 Killamarsh - Spinkhill - Staveley - Chesterfield A I 6 combined 7/8 combined 15/30 combined CG13 L R CG15 (1a) High Green - Ecclesfield village - Firth Park - Northern General Hospital - Burngreave - STREET B 71 First Rotherham - Canklow - Brinsworth - Tinsley Park - Attercliffe - Meadowhall 30 30 60 WEST BA CASTLEGATE Sheffield - Newfield Green - Hemsworth - Herdings R 81.82 83.83a Victoria Supertram line and stop W 3 First Nether Edge - Sheffield - Pitsmoor - Northern General Hospital - Firth Park - Wincobank - 10 12 20/30 72/72a First Sheffield - Parkway Markets - Handsworth - Waverley - (Treeton 72a) - Brinsworth - 30 30 60 (72a) 85.88 CG16 5.32.35.70.71.265 A Quays Rotherham 31.31a.57.61.62 I Meadowhall CG6 SNIG HILL 1.1a CG12 N 81.82.85.86