Download the Issue As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Air Force OA-X Light Attack Aircraft/SOCOM Armed Overwatch Program

Updated March 30, 2021 Air Force OA-X Light Attack Aircraft/SOCOM Armed Overwatch Program On October 24, 2019, the U.S. Air Force issued a final OA-X, its ability to operate with coalition partners, and to request for proposals declaring its intent to acquire a new initially evaluate candidate aircraft. The first phase included type of aircraft. The OA-X light attack aircraft is a small, four aircraft: the Sierra Nevada/Embraer A-29; two-seat turboprop airplane designed for operation in Textron/Beechcraft AT-6B; Air Tractor/L3 OA-802 relatively permissive environments. The announcement of a turboprops, variants of which are in service with other formal program followed a series of Air Force countries; and the developmental Textron Scorpion jet. “experiments” to determine the utility of such an aircraft. First-phase operations continued through August 2017. Following conclusion of the Air Force experiments, the program passed to U.S. Special Operations Command as Figure 1. Sierra Nevada/Embraer A-29 the “Armed Overwatch” program, with a goal of acquiring 75 aircraft. Why Light Attack? During 2018, then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson often expressed the purpose of a new light attack aircraft as giving the Air Force an ability to free up more sophisticated and expensive assets for other tasks, citing the example of using high-end F-22 jets to destroy a drug laboratory in Afghanistan as an inefficient use of resources. Per-hour operating costs for light attack aircraft are typically about 2%-4% those of advanced fighters. She and other officials have also noted that the 2018 Source: U.S. -

The Quandary of Allied Logistics from D-Day to the Rhine

THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 Director: Dr. Wade G. Dudley Program in American History, Department of History This thesis analyzes the Allied campaign in Europe from the D-Day landings to the crossing of the Rhine to argue that, had American and British forces given the port of Antwerp priority over Operation Market Garden, the war may have ended sooner. This study analyzes the logistical system and the strategic decisions of the Allied forces in order to explore the possibility of a shortened European campaign. Three overall ideas are covered: logistics and the broad-front strategy, the importance of ports to military campaigns, and the consequences of the decisions of the Allied commanders at Antwerp. The analysis of these points will enforce the theory that, had Antwerp been given priority, the war in Europe may have ended sooner. THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 © Parker Roberson, 2018 THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Dr. Wade G. Dudley, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Gerald J. Prokopowicz, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Michael T. Bennett, Ph.D. CHAIR OF THE DEP ARTMENT OF HISTORY: Dr. Christopher Oakley, Ph.D. DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL: Dr. Paul J. -

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1 WELCOME TO Pacifica Military History FREE SAMPLE CHAPTERS *** The 28 sample chapters in this free document are drawn from books written or co-written by noted military historian Eric Hammel. All of the books are featured on the Pacifca Military History website http://www.PacificaMilitary.com where the books are for sale direct to the public. Each sample chapter in this file is preceded by a line or two of information about the book's current status and availability. Most are available in print and all the books represented in this collection are available in Kindle editions. Eric Hammel has also written and compiled a number of chilling combat pictorials, which are not featured here due to space restrictions. For more information and links to the pictorials, please visit his personal website, Eric Hammel’s Books. All of Eric Hammel's books that are currently available can be found at http://www.EricHammelBooks.com with direct links to Amazon.com purchase options, This html document comes in its own executable (exe) file. You may keep it as long as you like, but you may not print or copy its contents. You may, however, pass copies of the original exe file along to as many people as you want, and they may pass it along too. The sample chapters in this free document are all available for free viewing at Eric Hammel's Books. *** Copyright © 2009 by Eric Hammel All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Cost of Replacing Today's Air Force Fleet

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE The Cost of Replacing Today’s Air Force Fleet DECEMBER 2018 Notes The years referred to in this report are federal fiscal years, which run from October 1 to September 30 and are designated by the calendar year in which they end. All costs are expressed in 2018 dollars. For the years before 2018, costs are adjusted for inflation using the gross domestic product price index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Costs for years after 2018 are adjusted for inflation using the Congressional Budget Office’s projection of that index. On the cover: An F-15C Eagle during takeoff. U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sergeant Joe W. McFadden. www.cbo.gov/publication/54657 Contents Summary 1 Today’s Air Force Aircraft and Their Replacement Costs 1 BOX 1. MAJOR AIRCRAFT IN THE AIR FORCE’S FLEET AND THEIR PRIMARY FUNCTIONS 2 How CBO Made Its Projections 5 Projected Costs of New Fighter Aircraft 6 F-35A 7 Light Attack Aircraft 7 Penetrating Counter Air Aircraft 8 Managing Procurement Costs in Peak Years 9 Appendix: Composition of the Current Air Force Fleet and CBO’s Estimate of Replacement Costs 11 List of Tables and Figures 18 About This Document 19 The Cost of Replacing Today’s Air Force Fleet Summary different missions (seeBox 1 and the appendix). They The U.S. Air Force has about 5,600 aircraft, which range range widely in age from the 75 new aircraft that entered in age from just-delivered to 60 years old. -

P-38 Lightning

P-38 Lightning P-38 Lightning Type Heavy fighter Manufacturer Lockheed Designed by Kelly Johnson Maiden flight 27 January 1939 Introduction 1941 Retired 1949 Primary user United States Army Air Force Produced 1941–45 Number built 10,037[1] Unit cost US$134,284 when new[2] Variants Lockheed XP-49 XP-58 Chain Lightning The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was a World War II American fighter aircraft. Developed to a United States Army Air Corps requirement, the P-38 had distinctive twin booms with forward-mounted engines and a single, central nacelle containing the pilot and armament. The aircraft was used in a number of different roles, including dive bombing, level bombing, ground strafing, photo reconnaissance missions,[3] and extensively as a long-range escort fighter when equipped with droppable fuel tanks under its wings. The P-38 was used most extensively and successfully in the Pacific Theater of Operations and the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations, where it was flown by the American pilots with the highest number of aerial victories to this date. The Lightning called "Marge" was flown by the ace of aces Richard Bong who earned 40 victories. Second with 38 was Thomas McGuire in his aircraft called "Pudgy". In the South West Pacific theater, it was a primary fighter of United States Army Air Forces until the appearance of large numbers of P-51D Mustangs toward the end of the war. [4][5] 1 Design and development Lockheed YP-38 (1943) Lockheed designed the P-38 in response to a 1937 United States Army Air Corps request for a high- altitude interceptor aircraft, capable of 360 miles per hour at an altitude of 20,000 feet, (580 km/h at 6100 m).[6] The Bell P-39 Airacobra and the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk were also designed to meet the same requirements. -

Corona KH-4B Satellites

Corona KH-4B Satellites The Corona reconnaissance satellites, developed in the immediate aftermath of SPUTNIK, are arguably the most important space vehicles ever flown, and that comparison includes the Apollo spacecraft missions to the moon. The ingenuity and elegance of the Corona satellite design is remarkable even by current standards, and the quality of its panchromatic imagery in 1967 was almost as good as US commercial imaging satellites in 1999. Yet, while the moon missions were highly publicized and praised, the CORONA project was hidden from view; that is until February 1995, when President Clinton issued an executive order declassifying the project, making the design details, the operational description, and the imagery available to the public. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has a web site that describes the project, and the hardware is on display in the National Air and Space Museum. Between 1960 and 1972, Corona satellites flew 94 successful missions providing overhead reconnaissance of the Soviet Union, China and other denied areas. The imagery debunked the bomber and missile gaps, and gave the US a factual basis for strategic assessments. It also provided reliable mapping data. The Soviet Union had previously “doctored” their maps to render them useless as targeting aids and Corona largely solved this problem. The Corona satellites employed film, which was returned to Earth in a capsule. This was not an obvious choice for reconnaissance. Studies first favored television video with magnetic storage of images and radio downlink when over a receiving ground station. Placed in an orbit high enough to minimize the effects of atmospheric drag, a satellite could operate for a year, sending images to Earth on a timely basis. -

Jacques Tiziou Space Collection

Jacques Tiziou Space Collection Isaac Middleton and Melissa A. N. Keiser 2019 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series : Files, (bulk 1960-2011)............................................................................... 4 Series : Photography, (bulk 1960-2011)................................................................. 25 Jacques Tiziou Space Collection NASM.2018.0078 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Jacques Tiziou Space Collection Identifier: NASM.2018.0078 Date: (bulk 1960s through -

Operational Requirements for Soldier-Robot Teaming

CAN UNCLASSIFIED Operational Requirements for Soldier-Robot Teaming Simon Banbury Kevin Heffner Hugh Liu Serge Pelletier Calian Ltd. Prepared by: Calian Ltd. 770 Palladium Drive Ottawa, Canada K2V 1C8 Contractor Document Number: DND-1144.1.1-01 PSPC Contract Number: W7719-185397/001/TOR Technical Authority: Ming Hou, DRDC – Toronto Research Centre Contractor's date of publication: August 2020 The body of this CAN UNCLASSIFIED document does not contain the required security banners according to DND security standards. However, it must be treated as CAN UNCLASSIFIED and protected appropriately based on the terms and conditions specified on the covering page. Defence Research and Development Canada Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2020-C172 November 2020 CAN UNCLASSIFIED CAN UNCLASSIFIED IMPORTANT INFORMATIVE STATEMENTS This document was reviewed for Controlled Goods by Defence Research and Development Canada using the Schedule to the Defence Production Act. Disclaimer: This document is not published by the Editorial Office of Defence Research and Development Canada, an agency of the Department of National Defence of Canada but is to be catalogued in the Canadian Defence Information System (CANDIS), the national repository for Defence S&T documents. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Department of National Defence) makes no representations or warranties, expressed or implied, of any kind whatsoever, and assumes no liability for the accuracy, reliability, completeness, currency or usefulness of any information, product, process or material included in this document. Nothing in this document should be interpreted as an endorsement for the specific use of any tool, technique or process examined in it. Any reliance on, or use of, any information, product, process or material included in this document is at the sole risk of the person so using it or relying on it. -

Chapter 1 a Theoretical and Observational Overview of Brown

Chapter 1 A theoretical and observational overview of brown dwarfs Stars are large spheres of gas composed of 73 % of hydrogen in mass, 25 % of helium, and about 2 % of metals, elements with atomic number larger than two like oxygen, nitrogen, carbon or iron. The core temperature and pressure are high enough to convert hydrogen into helium by the proton-proton cycle of nuclear reaction yielding sufficient energy to prevent the star from gravitational collapse. The increased number of helium atoms yields a decrease of the central pressure and temperature. The inner region is thus compressed under the gravitational pressure which dominates the nuclear pressure. This increase in density generates higher temperatures, making nuclear reactions more efficient. The consequence of this feedback cycle is that a star such as the Sun spend most of its lifetime on the main-sequence. The most important parameter of a star is its mass because it determines its luminosity, ef- fective temperature, radius, and lifetime. The distribution of stars with mass, known as the Initial Mass Function (hereafter IMF), is therefore of prime importance to understand star formation pro- cesses, including the conversion of interstellar matter into stars and back again. A major issue regarding the IMF concerns its universality, i.e. whether the IMF is constant in time, place, and metallicity. When a solar-metallicity star reaches a mass below 0.072 M ¡ (Baraffe et al. 1998), the core temperature and pressure are too low to burn hydrogen stably. Objects below this mass were originally termed “black dwarfs” because the low-luminosity would hamper their detection (Ku- mar 1963). -

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan The Early Years – 1954- 1974 Early Years Overview - The idea for the Chapter actually got started in June of 1954, when a group of Convair engineers got together over coffee at the old La Mesa airport. The four were Bjorn Andreasson, Frank Hernandez, Ladislao Pazmany, and Ralph Wilcox. - The group applied for a Chapter Charter which was granted two years later, on October 5, 1956. - Frank Hernandez was Chapter President for the first seven years of the Chapter, ably assisted by Ralph Wilcox as the Vice President. Frank later served as VP as well. The first four first flights of Chapter members occurred in 1955 and 1957. They were: Lloyd Paynter – Corbin; Sam Ursham - Air Chair; Frank Hernandez - Rapier 65; and Waldo Waterman - Aerobile. - A folder in our archives described the October 15-16, 1965 Ramona Fly-in which was sponsored by our chapter. Features: -Flying events: Homebuilts, antiques, replicas, balloon burst competition and spot landing competitions. - John Thorp was the featured speaker. - Aerobatic display provided by John Tucker in a Starduster. - Awards given: Static Display; Safety; Best Workmanship; Balloon Burst; Aircraft Efficiency; Spot Landings. According to an article published in 1997, in 1969 we hosted a fly-In in Ramona that drew 16,000 people. Some Additional Dates, Numbers, Activities June 1954: 7 members. First meeting was held at the old La Mesa Airport. 1958: 34 members. First Fly-in was held at Gillespie Field. 1964: 43 members. Had our first Chapter project: ten PL-2’s were begun by ten Chapter 14 members. -

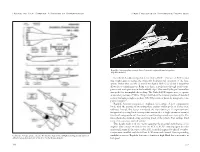

Facing the Heat Barrier: a History of Hypersonics First Thoughts of Hypersonic Propulsion

Facing the Heat Barrier: A History of Hypersonics First Thoughts of Hypersonic Propulsion Republic’s Aerospaceplane concept showed extensive engine-airframe integration. (Republic Aviation) For takeoff, Lockheed expected to use Turbo-LACE. This was a LACE variant that sought again to reduce the inherently hydrogen-rich operation of the basic system. Rather than cool the air until it was liquid, Turbo-Lace chilled it deeply but allowed it to remain gaseous. Being very dense, it could pass through a turbocom- pressor and reach pressures in the hundreds of psi. This saved hydrogen because less was needed to accomplish this cooling. The Turbo-LACE engines were to operate at chamber pressures of 200 to 250 psi, well below the internal pressure of standard rockets but high enough to produce 300,000 pounds of thrust by using turbocom- pressed oxygen.67 Republic Aviation continued to emphasize the scramjet. A new configuration broke with the practice of mounting these engines within pods, as if they were turbojets. Instead, this design introduced the important topic of engine-airframe integration by setting forth a concept that amounted to a single enormous scramjet fitted with wings and a tail. A conical forward fuselage served as an inlet spike. The inlets themselves formed a ring encircling much of the vehicle. Fuel tankage filled most of its capacious internal volume. This design study took two views regarding the potential performance of its engines. One concept avoided the use of LACE or ACES, assuming again that this craft could scram all the way to orbit. Still, it needed engines for takeoff so turbo- ramjets were installed, with both Pratt & Whitney and General Electric providing Lockheed’s Aerospaceplane concept.