Does Governance Improve with Globalisation? a Case Study of Village Level Institutions in Maharashtra, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Offices

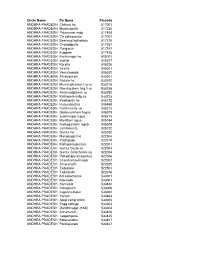

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Dr. Sachinkumar B.Patil

CURRICULAM VITAE Dr. Sachinkumar B.Patil B.Sc. , MLISc. , SET, NET, Ph.D. __________________________________________________________ GENERAL INFORMATION AND BACKGROUND Name : Dr. Sachinkumar Balasaheb Patil Date of Birth : 03/04/1983 Department : Library and Information Science, Shivaji University, Kolhapur - 416004 Designation : Assistant Professor Present Address : 530/11-12 E Ward, Flat No. 105, D.S.Park, Ingalenagar Kolhapur-416001 Permanent Address : C/O. - Mr.B.R.Patil, Sutar Galli, A/P - Jarandi, . Tal. - Tasgaon, Dist. - Sangli. Mobile No. : 9766482782 (M) : 0231-2609390 (O) E-mail : [email protected] Working Experience : - As a Librarian, Smt. Mathubai Garware Kanya Mahavidyalaya, Sangli from 18/12/2008 to 30/6/2017 [8 Years & 6 Months] 1 - At present as a Assistant Professor, Department of Library & Information Science, Shivaji University, Kolhapur [From 1/7/2017] Academic Achievements : Shri. B.N. Keskar Merit Award of Shivaji University, Kolhapur [Year 2006] Research Guidance : 5 Sudents of MLISc. Research Interests : Bibliometrics, Scientometrics, Stress Management, Social Media Analytics Research IDs : ORCid - https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8086-5025 Google Scholar - 35t6r6IAAAAJ Languages Known : Marathi, Hindi, and English ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS (FROM GRADUATION) Examination Name of the Year of Percentage Class Subject Board/University Passing of Marks Obtained Shivaji University, B.Sc. Kolhapur 2003 59.52 Higher Zoology Second Shivaji University, B.Lib.I.Sc. Kolhapur 2006 70.89 Distinction Library & Information Science Shivaji University, M.Lib.I.Sc. Kolhapur 2007 63.33 First Library & Information Science NET U.G.C. , New Delhi 2007 -- -- Library & Information Science SET Savitribai Phule Pune University, 2014 -- -- Library & Pune As a SET Information Science Agency Ph.D. -

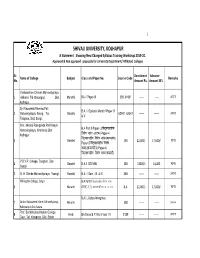

New Changed Syllabus 2019-20.Pdf

0 SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR A Statement Showing New Changed Syllabus Training Workshop 2019-20. Approved & Non approved proposals for University Department/ Affiliated Colleges Sr. Sanctioned Advance Name of College Subject Class and Paper No. Course Code Remarks No. Amount Rs. Amount 80% Yashwantrao Chavan Mahavidyalaya, 1 Halkarni, Tal-Chandgad, Dist. Marathi BA-II Paper-III 388, 61931 ------ ----- vekU; Kolhapur Sjri.Raosaheb Ramrao Pati B.A. II Optional Marathi Paper III 2 Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj, Tal. Marathi 62041, 62341 ------ ------ vekU; & V Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli. Smt. Akkatai Ramgonda Patil Kanya Mahavidyalaya, Ichalkarnji Dist: B.A Part II Paper- 3 वयाशाखीय Kolhapur. वशेष गाभा (नाटक ) Paper-4 वयाशाखीय वशेष गाभा (कायगंध ) 3 Marathi 388 22,000/- 17,600/- ekU; Paper-5 वयाशाखीय वशेष गाभा (आमचर ) Paper-6 वयाशाखीय वशेष गाभा (कादंबर ) P.D.V.P. College, Tasgaon, Dist- 4 Marathi B.A.II IDS/HML 388 18000/- 14,400 ekU; Sangli 5 M. H. Shinde Mahavidyalaya, Tisangi, Marathi B.A. II Sem - III & IV 388 ------ ------ vekU; Willingdon College, Sangli B.A.Part II fo|k'kk[kh; fo'ks"k xkHkk 6 Marathi (DSC-C1) vH;klif=dk dz- 3 o 5 B.A. 22,000/- 17,600/- ekU; B.A.II, Gadya Wangmay 7 Sardar Babasaheb Mane Mahavidyalaya, Marathi 388 ------ ------ vekU; Rahimatpur,Dist-Satara Prof. Sambhajirao Kadam College, 8 Hindi BA Second P. No.IV and VI 3129 ------ ------ vekU; Deur, Tal. Koregaon, Dist. Satara Sr. Sanctioned Advance Name of College Subject Class and Paper No. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : Mr. SUTAR APPASAHEB PANDIT Permanent Address : A/P. Savlaj, Tal. Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli Pin- 416311, Maharashtra. Correspondence Address : Shri. Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Mahavidhyalaya, Savlaj. Tal. Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli- 416311 Phone ( Mobile No.) : +91 9665864787, + 91 7709811877 Email- ID : [email protected], [email protected] Personal Details: Date of Birth :01st , October, 1984 Marital Status : Married Gender : Male Nationality : Indian Religion : Hindu Caste : Panchal (O.B.C.) Hobbies : Reading & Listening Music Interest : Listening lectures & Anchoring Languages Known : Marathi, Hindi and English. Educational Details Course Board/University Year of Passing Percentage/ Class/Grade Grade Ph.D S.U.K Submitted - - NET UGC Mar. 2013 - - M.A. S.U.K Apr.2009 60.67 1st class (Geography) B.A. S.U.K Mar.2007 58.94 2nd Class (Geography) H.S.C. Pune Board Feb.2004 44.00 Pass Class S.S.C. Pune Board Mar.2002 71.81 1st Class with Distinction Other Qualification Course Board/ Year of Percentage Class/ Institution/Univ Passing / Grade Grade ersity Summer Training Programme Smt. P.C.C. of May 2012 A+ A+ in Geospatial Technologies & Arts & Sci., Application Under NRDMS Margaon, Goa Programme in DST, Govt. of India Rural Journalism & Mass S.U.K May 2011 66.50 A Communication MS-CIT MKCL July 2005 79.00 A+ Teaching Experience: College Years Post Asst. Professor (C.H.B.) Rayat Shikshan Sansta‟s 9 Years Shri. R.R. Patil Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj Work Experience in Various Committee’s at Collage Level: Committee Chairman/ -

Faculty Profile

F aculty Profile Faculty Name : Dr. Vinod Vitthal Pawar Date of Birth : 24th August, 1980 Subject : Geography Education Qualification : M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D., PGDDC Gender : Male Designation : Assistant Professor Address : A/p- Songaon, Tal- Jaoli, Dist- Satara Pin- 4150514(MS) Mobile no. : 9604042525 Email Id : [email protected] PAN : AUYPP0727B Appointment Date : 1st August, 2009 Educational Qualification: Sr. Qualified Board/ Subject Passing Percentage/ Class No Exams University Year Obtained Obtained Marks 1. PGDDC Shivaji Digital May 74% First Class University Cartography & 2018 With Kolhapur GIS Distinction 2. Ph.D. Shivaji Generation of April - - University Village 2017 Kolhapur Information System for Development Planning 3. M. Phil Tilak Rural Periodic Jan 2009 70.16% First Class Maharashtra Market Centers With Vidhyapith In Jaoli Taluka Distinction Pune 4. M.A. Shivaji Geography Mar 57.75% Second University 2003 Class Kolhapur 5. B.A. Shivaji Geography Mar 69.00% First Class University 2001 Kolhapur 6. 12th Kolhapur --- Mar 62.67% First Class Board 1998 7. 10th Kolhapur --- Mar 71.06% First Class Board 1996 With Distinction Other Qualification: Sr. Qualified Board/ Subject Passing Percentage/ Class No Exams University Year Obtained Obtained Marks MS-CIT Maharashtra Operating Oct 62.00% First Class Computer State Board Of System 2009 1. Course Technical Education, Mumbai Details of Service: Sr. Name Of The Institution Period Years No. 1. Arts And Commerce College, Medha June 2004 To 2009 06 Tal- Jaoli, Dist- Satara 2. Amdar Shashikant Shinde Mahavidyalay, 1st August to onward 09 Medha Tal- Jaoli, Dist- Satara Research Publication: Sr. Title with Page Name of Level ISSN/ Peer Impact No. -

PERSONAL PROFILE PERSONAL INFORMATION: 1 Name : Katkar

Photo PERSONAL PROFILE PERSONAL INFORMATION: 1 Name : Katkar Gautam Ganpati 2 Educational Qualification : M.A.NET,B.J. 3 Subject : History 4 Area of specialization : History 5 Designation : Assistant Professor 6 Date of Birth : 07/05/1973 7Gender: Male 8 Date of Appointment : 05/10/2009 9Date of Retirement: Radha Nivas,Killa Bhag ,Miraj, Tal –Miraj Dist.Sangli 10 Address : (MS) Office Address 117 Shukrwar Peth, Satara : Residential Address : Radha Nivas,Killa Bhag ,Miraj, Tal –Miraj Dist.Sangli (MS) 11. Phone Number Mobile : 9881550706 Resi.: : Office : 02162-280235 12. E-mail : [email protected] 13. Aadhaar No. (UIA) : 297867196436 14. Religion - Caste : Hindu- Mahar 15. Nationality: Indian 16. Teaching Experience : 9 Years A) EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION: Board/ Percentage Sr.No. Exam. Passed Year University / Grade NET 1 UGC NEW DELHI 2005 Master of Arts 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur 2003 B+ Bachelor of Arts 3 Shivaji University, Kolhapur 1995 B Bachelor of Journalism 4 YCMOU, Nashik 2008 B+ 5 HSC Kolhapur 1992 B 6 SSLC Karnataka 1990 B Page 1 of 10 B) RESEARCH EXPERIENCE & TRAINING: Research University where the Completed Title of work/Theses Stage work was carried out, Year & Grade M.Phil. lkaxyh ftYg;krhy fuoMd eafnjkapk Tilak Maharashtra Ph.D. LFkkiR;]f’kYidyk o lkaLd`frd In Process University, Pune vH;kl ¼b-l-10 os rs 17 os ‘krd) C) RESEARCH PROJECTS CARRIED OUT (MAJOR/MINOR) FUNDED BY GOVT./NGO/INDUSTRY Name of the Funds Academic Title of the Project funding Received Remarks Year Agency In Rs. Sardar Parshurambhau 90000 Patwardhan’s Policy 1 Towards Karnataka 1557- UGC 2011 -2015 1799 D) DETAILS OF THE REFRESHER/ORIENTATION/SHORT TERM COURSES ATTENDED Orientation/ Refresher Course Name of ASC / University Date Academic Staff College,Goa 21/03/2017 to 1 Orientation Course University Goa 17/04/2017 2 Refresher course Page 2 of 10 RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS IN THE JOURNALS AND PROCEEDING WITH ISSN/ISBN NUMBERS SR.NO. -

Shri. Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj, Tal: Tasgaon

Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of Rayat Shiksahan Sanstha’s Shri. Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj, Tal: Tasgaon, Dist: Sangali Accredited Institution (As per the revised of October 2013) For the Academic Year 2017-18 Submitted on 25th December 2018 NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL An Autonomous Institution of the University Grants Commission P. O. Box. No. 1075, Opp: NLSIU, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore - 560 072 India S.R.R. Patil Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj, Tal: Tasgaon, Dist: Sangli (M.S) AQAR for 1st July 2017 to 30th June 2018 Page 1 Contents Page Nos. Part – A 1. Details of the Institution ...... 3 2. IQAC Composition and Activities ...... 7 Part – B 3. Criterion – I: Curricular Aspects ...... 9 4. Criterion – II: Teaching, Learning and Evaluation ...... 10 5. Criterion – III: Research, Consultancy and Extension ...... 12 6. Criterion – IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources ...... 17 7. Criterion – V: Student Support and Progression ...... 19 8. Criterion – VI: Governance, Leadership and Management ...... 22 9. Criterion – VII: Innovations and Best Practices ...... 26 10. Plans of Institution for Next Year ....... 29 11. Annexure-I …… 30 12. Annexure- II ....... 31 13. Annexure-III ...... 33 14. Annexure-IV ...... 34 15. Annexure-V ...... 35 ___________________________ S.R.R. Patil Mahavidyalaya, Savlaj, Tal: Tasgaon, Dist: Sangli (M.S) AQAR for 1st July 2017 to 30th June 2018 Page 2 The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Part – A 1. Details of the Institution Rayat Shikshan Sanstha‘s 1.1 Name of the Institution Shri. Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Mahavidyalaya 1.2 Address Line 1 A/P: Savlaj Address Line 2 Tal: Tasgaon City/Town Dist: Sangali Maharashtra State Pin Code 416311 [email protected] Institution e-mail address Contact Nos. -

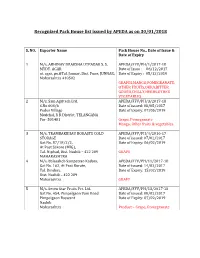

Recognized Pack House List Issued by APEDA As on 30/01/2018

Recognized Pack House list issued by APEDA as on 30/01/2018 S. NO. Exporter Name Pack House No., Date of Issue & Date of Expiry 1 M/s. ABHINAV DRAKSHA UTPADAK S. S. APEDA/FFV/PH/1/2017-18 MYDT. AGAR Date of Issue : 06/12/2017 at. agar, po.&Tal. Junnar, Dist. Pune, JUNNAR, Date of Expiry : 05/12/2019 Maharashtra 410502 GRAPES,MANGO,POMEGRANATE, OTHER FRUITS,OKRA,BITTER GOURD,CHILLY,HERBS,OTHER VEGETABLES 2 M/s. Sam Agritech Ltd. APEDA/FFV/PH/3/2017-18 S.No 608/6 Date of issued: 08/05/2017 Pudur Village Date of Expiry: 07/05/2019 Medchal, R R District, TELANGANA Pin- 501401 Grape, Pomegranate Mango, Other fruits & vegetables. 3 M/s. TRAMBAKBHAU BORASTE COLD APEDA/FFV/PH/4/2016-17 STORAGE Date of issued: 07/02/2017 Gat No. 87/1B/2/2, Date of Expiry: 06/02/2019 At Post Sakore (MIG), Tal. Niphad, Dist. Nashik – 422 209 GRAPE MAHARASHTRA 4 M/s. Balasaheb Sampatrao Kadam, APEDA/FFV/PH/11/2017-18 Gat No. 162, At Post Korate, Date of issued: 14/02/2017 Tal. Dindori, Date of Expiry: 15/02/2019 Dist. Nashik – 422 209 Maharashtra GRAPE 5 M/s. Seven Star Fruits Pvt. Ltd. APEDA/FFV/PH/13/2017-18 Gat No. 454, Pimpalgaon Vani Road Date of issued: 08/02/2017 Pimpalgaon Baswant Date of Expiry: 07/02/2019 Nashik Maharashtra Product – Grape, Pomegranate 6 M/s. Parik Grapes APEDA/FFV/PH/14/2014-15 Gat No. 107 Date of issued: 17/02/2015 At Post Dahegaon(Vahegaon) Date of Expiry: 16/02/2017 Tal Niphad Dist. -

Final List of Contesting Candidates

GENERAL ELECTION TO MAHARASHTRA STATE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY-2014 List of Contesting Candidates MAHARSHTRA STATE DATE OF POLL 15TH OCTOBER 2014 Sr. No. Name Of Candidate Address Of Candidate Party Affiliation Symbol Allottted 1-Akkalkuwa (ST) 1 Aamshya Fulji Padavi At- Koylivihir, Post - British Ankushvihir Tal- Akkalkuwa Shivsena Bow And Arrow Dist- Nandurbar 2 Paradake Vijaysing Rupsing At June Dhadgaon, Post- Dhadgaon Tal- Akrani Dist- Nationalist Congress Party Clock Nandurbar 3 Padavi Adv. K.C. At Asali, Post Talai, Tal- Akkalkuwa Dist- Nandurbar Indian National Congress Hand 4 Padavi Nagesh Dilwarsing At Post Vanyavihir, Tal - Akkalkuwa Dist- Nandurbar Bharatiya Janata Party Lotus 5 Mamata Ravindra Valavi At Post Mundalvad, Tal- Akrani Dist- Nandurbar Maharashtra Navnirman Sena Railway Engine 6 Adv. Ranjit Jugla Padavi At Danel, Post- Bhagdari Tal- Akkalkuwa Dist- Bahujan Mukti Party Cot Nandurbar 7 Padavi Narendrasing Bhagatsing At- Sorapada, Post- Akkalkuwa Tal- Akkalkuwa, Dist - Independent Cup And Saucer Nandurbar 8 Padavi Madhukar Shamsing At- Khatwani, Post- British Ankushvihir Tal- Akkalkuwa, Independent Slate Dist- Nandurbar 9 Madan Jahangir Padavi At Post- Jamana, Tal- Akkalkuwa, Dist- Nandurbar Independent Table 2-Sahada (ST) 1 Kisan Runjya Pawar Balaji, 35-Bramhastrushti Colony, Juna Mohida Road, Maharashtra Navnirman Sena Railway Engine Post Shahada, Tal. Shahada, Dist.Nandurbar Shahada 2 Gavit Rajendrakumar Krushnarao Plot No.5, Pratap Nagar, Taloda, Tal.Taloda Nationalist Congress Party Clock Dist.Nandurbar Taloda 3 Naik Suresh Sumersing At.Post Chikhali Digar Tal.Shahada Dist.Nandurbar Shivsena Bow And Arrow Chikhali Digar 4 Padmakar Vijaysing Valvi At.Post Modalpada, Tal.Taloda Dist.Nandurbar Indian National Congress Hand Modalpada 5 Padvi Udesing Kocharu At.Somaval Bk, Post.Nalgavhan, Tal.Taloda, Bharatiya Janata Party Lotus Dist.Nandurbar At.Somaval Bk Post.Nalgavhan 6 Padvi Savitri Magan At Post. -

Annexure-I CA LIST for FRUITS & VEGETABLE

Annexure-I C.A. LIST FOR FRUITS & VEGETABLE (TABLE GRAPE/POMOGRANATE/ONION) FOR EXPORT NASHIK SUB-OFFICE Sl.N Name & Address of party C.A.No. Commodity C.A. expiry date Grading in Pack Houses o. approved Approved by APEDA 01 M/s. Earth Fresh Fruits Pvt. Ltd, A/1 31/03/2017 M/s.Vegetable & Fruits co-operative marketing society Ltd., Gat A/503, Redwood, Vasant No-003724 31/3/2013 No.90, Vinchur Road, Lasalgaon, Tal Niphad Dist. Nashik.Canal Garden, Mulund(W), Mumbai. Bagaidar Sangh, Post Ozar(Mig) Mumbai-agra road, Dist Nashik. 02 Kshirsagar Cold Storage, At: A/1No. 31/3/2016 Table Grapes 1.M/s. Vijayshree Exports, Gat No. 87, Railway Stn Rd, Ugaon At: Shivdi Tal: Niphad Dist: Nashik 003578 Shivdi Tal: Niphad 2. Kshirsagar Cold Storage,A/p: Kokan gaon Tal: Niphad Dist: Nashik. 03 M/s.Farmland A/1 31/03/2013 Table Grapes N.D.Grape Pvt.Ltd., Gat No.99, Post Godegaon, Tal.Dindori , Dist. Export,17/18,Patel Building, No.003904 Nashik. M.K.Amin Road, Fort, Mumbai 04 Shree Gajanan Impex, A/p: A/1No. 31/3/2013 Table Grapes M/s.Canal Bagaithar Sah. Sangh Ltd.,Ozar(Mig) Tal: Niphad Dist: Chandori, Tal: Niphad, Dist: 003908 Nashik Nashik 05 M/s.Kohilico Foods & A/1 No- 31/03/2013 Table Grapes 1) Shree Durga Fresh Fruits& Foods Beverages Pt. Ltd., 390 Mahesh 003910 GAT No 126/1B & 2B Kadwa Chamber,Narsi Natha Mhalungi Near Seagram Street,Mumbai-9 Distilleries Tal Dindori DisttNashik 2) Gangotri Agro Exports At Post: Dawachwadi-422 209Tal.