Prometheus, Hermes, and Other Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Prometheus C Prometheus Helios Helios Hd

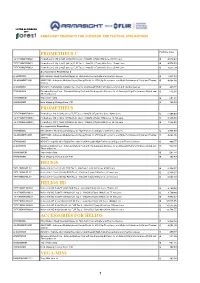

LISTINO AL PUBBLICO 2017 ARMASIGHT PRODUCTS FOR OUTDOOR AND TACTICAL APPLICATIONS PROMETHEUS C Pubblico ivato TAT179MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (9 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 9Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.078,63 TAT173MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (30 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 30Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.078,63 TAT176MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (60 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 60Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.247,79 Accessories for Prometheus C ATVR000002 IRIS Wireless Head Mounted Display for High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €2.836,03 IALA00AMRF22001 AMRF2200 - Advanced Modular (Laser) Range Finder for LFR Clip-On systems, and High- Performance Digital and Thermal €4.604,90 devices ATAM000005 HD DVR - High-Definition Digital Recorder for all Armasight High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €490,77 ATAM000008 Extended Battery Pack - Extended Battery Pack with Rechargeable Batteries for all Armasight High-Performance Digital and €542,98 Thermal devices ANAMTM0003 Tripod with a Grip €501,21 ANHC000001 Hard Shipping/ Storage Case #101 €162,89 PROMETHEUS TAT179MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (9 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 9Hz Core, 42mm Lens €5.306,60 TAT173MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (30 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 30Hz Core, 42 mm Lens €5.306,60 TAT176MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (60 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 60Hz Core, 42 mm Lens €5.548,85 Accessories for Prometheus ATVR000002 IRIS Wireless Head Mounted Display for High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €2.836,03 IALA00AMRF22001 -

Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville

Trickster's Way Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-2003 Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/trickstersway Recommended Citation Neville, Bernie (2003) "Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes ," Trickster's Way: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/trickstersway/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trickster's Way by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neville: Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Trickster's Way Vol 2 Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville The Story of Our Times For the past half century, we have been hearing from various sources that human consciousness and culture is undergoing some sort of transformation.[1] The story we hear is sometimes the story of a collapsing civilization and an inevitable global catastrophe and sometimes a story of a coming bright new age, but the pessimistic and optimistic versions have certain themes in common when they address the nature of th contemporary world. The story we hear is a story of complexity and chaos, of the dissolution of boundaries, of deceit, denial and delusion, of the preference for image over substance, of the loss o familial and tribal bonds, of the deregulation of markets, ideas and ethics, of an unwillingness of national leaders to confront reality and tell the truth, of the abandonment of rationality, of the proliferation of information, of a market-place so noisy that nothing can be clearly heard, of a world seen through a distorting lens, of an ever-tightening knot which we cannot unravel, or an ever-unraveling knot which we cannot tighten, of planetary dilemmas so profound that we cannot even think about them sensibly, let alone address them. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Read Book ^ Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate

[PDF] Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys,... Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, Asteria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, Astraeus, Cron Book Review A superior quality pdf along with the font used was intriguing to read through. It can be rally exciting throgh reading through time period. You may like how the blogger create this book. (Dr. Rylee Berg e) TITA NS: ATLA S, TITA N, RHEA , HELIOS, EOS, PROMETHEUS, HECATE, OCEA NUS, METIS, MNEMOSYNE, TITA NOMA CHY, SELENE, THEMIS, TETHYS, THEIA , IA PETUS, COEUS, CRIUS, A STERIA , EPIMETHEUS, HYPERION, A STRA EUS, CRON - To download Titans: A tlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, A steria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, A straeus, Cron PDF, you should access the web link under and save the ebook or have accessibility to other information which are have conjunction with Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, Asteria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, Astraeus, Cron book. » Download Titans: A tlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, A steria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, A straeus, Cron PDF « Our solutions was introduced with a want to serve as a total on the internet electronic digital catalogue that provides use of multitude of PDF file book assortment. You could find many kinds of e-publication and also other literatures from your paperwork database. -

Myth and Origins: Men Want to Know

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, October 2015, Vol. 5, No. 10, 930-945 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2015.10.013 D DAVID PUBLISHING Myth and Origins: Men Want to Know José Manuel Losada Université Complutense, Madrid, Spain Starting with a personal definition of “myth”, this paper seeks to substantiate the claim that every myth is essentially etiological, in the sense that myths somehow express a cosmogony or an eschatology, whether particular or universal. In order to do that, this study reassesses Classical and Judeo-Christian mythologies to revisit and contrast the narratives of origin—of the cosmos, of the gods and of men—found in ancient polytheism and in Judeo-Christian monotheism. Taking into consideration how these general and particular cosmogonies convey a specific understanding of the passage of time, this article does not merely recount the cosmogonies, theogonies, and anthropogonies found in the Bible and in the works of authors from Classical Antiquity, but it also incorporates a critical commentary on pieces of art and literature that have reinterpreted such mythical tales in more recent times. The result of the research is the disclosure of a sort of universal etiology that may be found in mythology which, as argued, explains the origins of the world, of the gods, and of men so as to satisfy humankind’s ambition to unveil the mysteries of the cosmos. Myth thus functions in these cases as a vehicle that makes it possible for man to return the fullness of a primordial age, abandoning the fleeting time that entraps him and entering a time still absolute. -

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique Copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS BY LILIAN STOUGHTON HYDE YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2008 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC. Th is edition, fi rst published in 2008 by Yesterday’s Classics, an imprint of Yesterday’s Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by D. C. Heath and Company in 1904. For the complete listing of the books that are published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Online Children’s Literature Project which presents the complete text of hundreds of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com. ISBN-10: 1-59915-261-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-261-5 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 PREFACE In the preparation of this book, the aim has been to present in a manner suited to young readers the Greek myths that have been world favorites through the centuries, and that have in some measure exercised a formative infl uence on literature and the fi ne arts in many countries. While a knowledge of these myths is undoubtedly necessary to a clear understanding of much in literature and the arts, yet it is not for this reason alone that they have been selected; the myths that have appealed to the poets, the painters, and the sculptors for so many ages are the very ones that have the greatest depth of meaning, and that are the most beautiful and the best worth telling. -

Heterogeny in Analyses of the Greek God Hermes: a Systematic Review

Research and Reviews on Healthcare: Open Access Journal DOI: 10.32474/RRHOAJ.2020.05.000223 ISSN: 2637-6679 Review Article Heterogeny In Analyses of The Greek God Hermes: A Systematic Review Trevor C Hunt BA* College of Health Professions, The University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA *Corresponding author: Trevor C Hunt BA, College of Health Professions, 4035 S Riverpoint Pkwy, Phoenix, AZ, USA Received: October 02, 2020 Published: October 12, 2020 Abstract Hermes was the ancient Greek god of trade, wealth, luck, fertility, animal husbandry, sleep, language, thieves, and travel. One of the cleverest and most mischievous of the Olympian gods, he was the patron of shepherds, invented the lyre, and was, above all, the herald and messenger of Mt. Olympus so that he came to symbolize the crossing of boundaries in his role as a guide between the two realms of gods and humanity. To the Romans, the god was known as Mercury. Herein, we present a review of the literature expoundingKeywords: upon Urology; significant Hermes; heterogeneity Greek; Mythology; in the classicalReview understanding and interpretation of this figure within urology. Main Text extremely broad work that is the Theogony, Hermes is given some The Slayer of Argos; Keeper of the Flocks; Messenger of the of his most crucial traits. His power over animals and ability to Gods: all of these are epithets for the glorious Greek god Hermes make them mate and produce offspring is referenced early on in a that appear in the urologic literature. Indeed, Hermes is quite the passage speaking primarily of Hecate, who shares the same power multifaceted character in the Greek mythological tradition. -

Prometheus ©Twentieth Century Fox ©Twentieth Directed By: Ridley Scott

Prometheus ©Twentieth Century Fox ©Twentieth DirecteD by: Ridley Scott certificate: 15 running time: 123 mins country: UK/USA year: 2012 KeyworDs: science fiction, film franchise, action heroine, faith suitable for: 14–19 media/film studies, religious education www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites synoPsis Ridley Scott, director of ‘Alien’ and ‘Blade Runner,’ returns to the genre he helped define. With Prometheus, he creates a groundbreaking mythology, in which a team of explorers discover a clue to the origins of mankind on Earth, leading them on a thrilling journey to the darkest corners of the universe. There, they must fight a terrifying battle to save the future of the human race. before Viewing the original ‘alien’ series Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) – Aliens (James Cameron, 1986) – Alien 3 (David Fincher, 1992) – Alien Resurrection (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997) Prometheus is an eagerly awaited science fiction adventure from Alien director Ridley Scott. In the run-up to its release, anticipation for this film was at fever pitch because it returns to a world created by Scott in the sci-fi horror classic Alien. The four original Alien films share certain things in common: ■ All were directed by visionary filmmakers at the very beginning of their career (Alien 3 was David Fincher’s first film and Alien Resurrection was the Hollywood debut of Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet). ■ Each film features the same female protagonist - Ripley (Sigourney eaver).W ■ Whilst all four are science fiction films, each has the framework of other genres. -

Flowers for Algernon

Si Summary Template Use this template to write a summary of a literary text. “How Fire Was Given to Men” SOMEBODY WANTED BUT SO THEN Who are the characters? What do the main What conflict or problem do What did the main How did the conflict resolve Which characters are the character(s) want to the main character(s) character(s) do in response itself? main characters? accomplish? encounter? to the problem? Jupiter and the Mighty Ones Prometheus wants to give Jupiter doesn’t want Prometheus sneaks fire to The humans become better Prometheus humans fire and help make humans to have fire because the humans and teaches and happy and Prometheus Humankind them better. he is worried they will take them lots of things. declares a new and brighter over. day will come. Jupiter and the Mighty Ones rule over humankind and want to keep them miserable. Prometheus feels badly and wants humans to have fire. Jupiter doesn’t want humans to have fire because he is worried they will take over the Mighty Ones. So, Prometheus sneaks fire to humans and teaches them lots of things. The humans become more knowledgeable and happy and Prometheus declares a new and brighter day will come. Revised summary: Jupiter and the Mighty Ones rule over humankind and want to keep them miserable. Prometheus wants to give humans fire and help make them better. However, Jupiter refuses to allow Prometheus to give fire to humankind. Jupiter doesn’t want humans to have fire because he is worried they will take control over the Mighty Ones. -

Deviant Origins: Hesiodic Theogony and the Orphica Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2018 Deviant Origins: Hesiodic Theogony and the Orphica Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .G 2018. "Deviant Origins: Hesiodic Theogony and the Orphica." In In Oxford Handbook of Hesiod, edited by A. Loney & S. Scully, 225-242. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/125 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Deviant Origins: Hesiod’s Theogony and the Orphica Oxford Handbooks Online Deviant Origins: Hesiod’s Theogony and the Orphica Radcliffe G. Edmonds III The Oxford Handbook of Hesiod Edited by Alexander C. Loney and Stephen Scully Print Publication Date: Sep 2018 Subject: Classical Studies, Classical Poetry, Classical Religions and Mythologies Online Publication Date: Aug 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190209032.013.43 Abstract and Keywords Hesiod’s Theogony provides one of the most widely authoritative accounts of the origin of the cosmos, but his account has always been challenged by rivals claiming to be older, wiser, and better, and the name of Orpheus has always been privileged in the evidence for ancient rivals to Hesiod. The Orphic accounts play their variations on the Hesiodic themes, riffing in different ways on the idea of the ultimate origin of the cosmos; the processes of reproduction by which subsequent entities were generated; the conflicts between these divinities that created the changes from the original state to the current one; the way in which humans entered the story; and the final resolution of the conflicts and changes that created the current, normal order of Zeus. -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34