Myth and Origins: Men Want to Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Zeus *God of the Sky and Ruler of the Olympian Gods. He Is Lord of the Sky, the Rain God

Greek Mythology *Myths - Traditional stories about god and heroes. *The Greek people believed in many gods and goddesses. They were thought to have affected people's lives and also thought to shape events. *The gods and goddesses were thought to control nature. Some examples of the control over nature are: Zeus ruled the sky and threw lighting bolts, Demeter made the crops grow, and Poseidon caused earthquakes. *The 12 most important gods and goddesses lived on Mt. Olympus. Mt. Olympus was the highest mountain in Greece. Zeus *God of the Sky and Ruler of the Olympian gods. He is lord of the sky, the rain god. *He is represented as the god of justice and mercy, the protector of the weak, and the punisher of the wicked. Poseidon *God of the sea and protector of all the water. *Widely worshiped by seamen. *His weapon is a trident, which can shake the earth, and shatter any object. *He is second only to Zeus in power amongst the gods. *He was greedy. He had a series of disputes with other gods when he tried to take over their cities. Hades *Hades is the god of the undedrworld and ruler of the dead. *He is also the god of wealth, due to the precious metals mined from the earth. *He is a greedy god who is greatly concerned with increasing his subjects. Hestia *She plays no part in myths. *She is the Goddess of the Hearth, the symbol of the house around which a new born child is carried before it is received into the family. -

Physiology and Mysticism at Pherai. the Funerary Epigram for Lykophron

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 15 | 2002 Varia Physiology and Mysticism at Pherai. The Funerary Epigram for Lykophron Aphrodite A. Avagianou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/1368 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.1368 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2002 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Aphrodite A. Avagianou, « Physiology and Mysticism at Pherai. The Funerary Epigram for Lykophron », Kernos [Online], 15 | 2002, Online since 21 April 2011, connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/1368 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.1368 Kernos Kernos 15 (2002), p. 75-89. Physiology and Mysticism at Pherai. The Funerary Epigram for Lykophron* Ta the starry heaven, where my saut will live. For historians of religion, a funerary epigram from Pherai dated to the early Hellenistic period1 has special interest. The text is as follows: Znvàc; ànà QU;,nc; IlEyéû,ou AUXOqJQillV 6 <PLÀLOXOU oo1;nL, àÀn8ElaL ôÈ Èx nUQàc; à8uvérrou' xut セキ Èv OÙQUVLOLC; èiOtQOLC; iJJtà nutQàc; àEQ8ElC;' oWIlU ôÈ IlntQàc; ÈlliiC; IlntÉQu yf\v XatÉXEL. I, Lykophron, the son of Philiskos, seem sprung from the root of great Zeus, but in truth am from the immortal fire; and l live among the heavenly stars uplifted by my father; but the body born of my mother oecupies mother-earth. The main idea of the epigram, that the soul of the dead goes to the astral heaven while the body returns to the earth, that is, the mother, is easy to grasp and it could be argued that this notion is a standard expression in funerary epigrams. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

7Th Grade Lesson Plan: It's Greek to Me: Greek Mythology

7th grade Lesson Plan: It’s Greek to me: Greek Mythology Overview This series of lessons was designed to meet the needs of gifted children for extension beyond the standard curriculum with the greatest ease of use for the edu- cator. The lessons may be given to the students for individual self-guided work, or they may be taught in a classroom or a home-school setting. This particular lesson plan is primarily effective in a classroom setting. Assessment strategies and rubrics are included. The lessons were developed by Lisa Van Gemert, M.Ed.T., the Mensa Foundation’s Gifted Children Specialist. Introduction Greek mythology is not only interesting, but it is also the foundation of allusion and character genesis in literature. In this lesson plan, students will gain an understanding of Greek mythology and the Olympian gods and goddesses. Learning Objectives Materials After completing the lessons in this unit, students l D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths by Ingri and will be able to: Edgar Parin D’Aulaire l Understand the Greek view of creation. l The Gods and Goddesses of Olympus by Aliki l Understand the terms Chaos, Gaia, Uranus, Cro- l The Mighty 12: Superheroes of Greek Myths by nus, Zeus, Rhea, Hyperboreans, Ethiopia, Mediter- Charles Smith ranean, and Elysian Fields. l Greek Myths and Legends by Cheryl Evans l Describe the Greek view of the world’s geogra- l Mythology by Edith Hamilton (which served as a phy. source for this lesson plan) l Identify the names and key features of the l A paper plate for each student Olympian gods/goddesses. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

Prometheus C Prometheus Helios Helios Hd

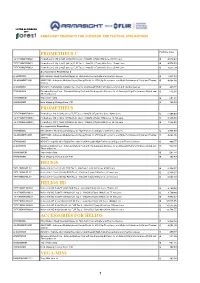

LISTINO AL PUBBLICO 2017 ARMASIGHT PRODUCTS FOR OUTDOOR AND TACTICAL APPLICATIONS PROMETHEUS C Pubblico ivato TAT179MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (9 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 9Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.078,63 TAT173MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (30 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 30Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.078,63 TAT176MN2PROC21 Prometheus C 336 2-8x25 (60 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 60Hz Core, 25 mm Lens €4.247,79 Accessories for Prometheus C ATVR000002 IRIS Wireless Head Mounted Display for High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €2.836,03 IALA00AMRF22001 AMRF2200 - Advanced Modular (Laser) Range Finder for LFR Clip-On systems, and High- Performance Digital and Thermal €4.604,90 devices ATAM000005 HD DVR - High-Definition Digital Recorder for all Armasight High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €490,77 ATAM000008 Extended Battery Pack - Extended Battery Pack with Rechargeable Batteries for all Armasight High-Performance Digital and €542,98 Thermal devices ANAMTM0003 Tripod with a Grip €501,21 ANHC000001 Hard Shipping/ Storage Case #101 €162,89 PROMETHEUS TAT179MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (9 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 9Hz Core, 42mm Lens €5.306,60 TAT173MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (30 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 30Hz Core, 42 mm Lens €5.306,60 TAT176MN4PROM31 Prometheus 336 3-12x42 (60 Hz) FLIR Tau 2 - 336x256 (17μm) 60Hz Core, 42 mm Lens €5.548,85 Accessories for Prometheus ATVR000002 IRIS Wireless Head Mounted Display for High-Performance Digital and Thermal devices €2.836,03 IALA00AMRF22001 -

Metamorphosis of Love: Eros As Agent in Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary France" (2017)

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2017 Metamorphosis of Love: Eros as Agent in Revolutionary and Post- Revolutionary France Jennifer N. Laffick University of Central Florida Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Laffick, Jennifer N., "Metamorphosis of Love: Eros as Agent in Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary France" (2017). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 195. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/195 METAMORPHOSIS OF LOVE: EROS AS AGENT IN REVOLUTIONARY AND POST-REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE by JENNIFER N. LAFFICK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Art History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2017 Thesis Chair: Dr. Margaret Zaho ABSTRACT This thesis chronicles the god of love, Eros, and the shifts of function and imagery associated with him. Between the French Revolution and the fall of Napoleon Eros’s portrayals shift from the Rococo’s mischievous infant revealer of love to a beautiful adolescent in love, more specifically, in love with Psyche. In the 1790s, with Neoclassicism in full force, the literature of antiquity was widely read by the upper class. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

MONEY and the EARLY GREEK MIND: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy

This page intentionally left blank MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND How were the Greeks of the sixth century bc able to invent philosophy and tragedy? In this book Richard Seaford argues that a large part of the answer can be found in another momentous development, the invention and rapid spread of coinage, which produced the first ever thoroughly monetised society. By transforming social relations, monetisation contributed to the ideas of the universe as an impersonal system (presocratic philosophy) and of the individual alienated from his own kin and from the gods (in tragedy). Seaford argues that an important precondition for this monetisation was the Greek practice of animal sacrifice, as represented in Homeric epic, which describes a premonetary world on the point of producing money. This book combines social history, economic anthropology, numismatics and the close reading of literary, inscriptional, and philosophical texts. Questioning the origins and shaping force of Greek philosophy, this is a major book with wide appeal. richard seaford is Professor of Greek Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of commentaries on Euripides’ Cyclops (1984) and Bacchae (1996) and of Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (1994). MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy RICHARD SEAFORD cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521832281 © Richard Seaford 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

Days Without End —Mortality and Immortality of Life Cycle— Kumi Ohno

(83) Days Without End —Mortality and Immortality of Life Cycle— Kumi Ohno Introduction Eugene O’Neill’s Days Without End (herein referred to as “Days” ) was premiered on December 27th, 1933 at Plymouth Theatre in Boston. The play consists of four acts and six scenes. The author tried to excavate the “crisis awareness” against an intrinsic nature of mankind through this play. In Dynamo which was written in 1929, O’Neill introduced four gods: “Puritan god”, “electricity god”, “Dynamo” and “the real god representing the eternal life”. In the story, however, Ruben, the main character, who seeks the salvation from these gods, is unable to find the true answer and commits suicide. In Days, the main character barely but successfully finds out the religious significance of the purpose of life and continues to have hope and the will to live, which is quite different from other O’Neill’s plays. This play was written in 1930s during the great economic depres sion and the anxiety of the people described in Dynamo is inherited by this play, although the subject is dug from the different aspect. However, as seen from the author’s efforts of rewriting the script several times, his attempts to reach the final conclusion was not successful for many years. The play was finally published after rewriting eight times during the period between 1931–1934.1 Days is considered to be the worst play of Eugene O’Neill. Ah, Wilderness!, which was highly acclaimed by the critics and which ran 289 performances, was written almost in the same 1 Doris V.