Laufenberg, D. and C. Woodward. 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecuador’s Biodiversity Hotspots Destination: Andes, Amazon & Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Duration: 19 Days Dates: 29th June – 17th July 2018 Exploring various habitats throughout the wonderful & diverse country of Ecuador Spotting a huge male Andean bear & watching as it ripped into & fed on bromeliads Watching a Eastern olingo climbing the cecropia from the decking in Wildsumaco Seeing ~200 species of bird including 33 species of dazzling hummingbirds Watching a Western Galapagos racer hunting, catching & eating a Marine iguana Incredible animals in the Galapagos including nesting flightless cormorants 36 mammal species including Lowland paca, Andean bear & Galapagos fur seals Watching the incredible and tiny Pygmy marmoset in the Amazon near Sacha Lodge Having very close views of 8 different Andean condors including 3 on the ground Having Galapagos sea lions come up & interact with us on the boat and snorkelling Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Gustavo (Andean Naturalist Guide) Day 1: Quito / Puembo Francisco (Antisana Reserve Guide) Milton (Cayambe Coca National Park Guide) ‘Campion’ (Wildsumaco Guide) Day 2: Antisana Wilmar (Shanshu), Alex and Erica (Amazonia Guides) Gustavo (Galapagos Islands Guide) Days 3-4: Cayambe Coca Participants Mr. Joe Boyer Days 5-6: Wildsumaco Mrs. Rhoda Boyer-Perkins Day 7: Quito / Puembo Days 8-10: Amazon Day 11: Quito / Puembo Days 12-18: Galapagos Day 19: Quito / Puembo Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview Ecuador may be a small country on a map, but it is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of life and biodiversity. -

EASTERN ECUADOR RARITIES Custom Tour/ Nov-Dec 2020

Tropical Birding Tours - Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR RARITIES Custom Tour/ Nov-Dec 2020 A Tropical Birding Tours CUSTOM BIRDING TOUR EASTERN ECUADOR RARITIES 26 Nov-6 Dec, 2020 Report and photos by ANDRES VASQUEZ N., the guide for this tour One of the most wanted birds of the World, the mighty queen of the jungle, Harpy Eagle (picture above at a nesting site). This is probably the easiest access to a nest of this awesome bird of prey in all of Latin America. It involves only a 5-minute car ride from the door of the hotel, 15 minute boat ride on the Napo River, and 2 easy walks of about 10 minutes each on flat but muddy terrain. The nesting pair has been recorded on this site a couple years ago by a local farmer who did not know much about the importance of the bird and therefore it remained “hidden” to the birding world until this year when the same farmer saw the couple again and this time mentioned it to the local guides who recently had been more active in terms of birding. The word spread out quickly and we were forced to tweak the itinerary that we already had for this custom tour and included a visit to the site. It was a tricky visit since just two days before our arrival, a group of scientists that visited the site recommended that no tourists should visit yet. However, since we were already there and it was only two visitors, we joined an already scheduled monitoring visit during which we stayed at the nest site for exactly 3.5 minutes, saw the bird, took a couple photos and left. -

Magpie Jay General Information and Care

Magpie Jay General Information and Care: Black Throated Magpie Jays (Calocitta colliei) and White Throated Magpie Jay (Calocitta formosa) are the only two species in their genus. Black Throated Magpie Jays are endemic to Northwestern Mexico. The range of White Throated Magpie Jays lies to the south, overlapping with Black Throats slightly in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Colima, and running into Costa Rica. Both of these birds are members of the family Corvidae. Magpie Jays are energetic, highly intelligent animals and need to be kept in a large planted aviary - not just a cage. These birds are highly social and are commonly found in the wild as cooperative nesters. They are omnivores and favor a great variety of fruits, insects, small rodents, and nuts. A captive diet that works well in my aviaries is a basic pellet low iron softbill diet such as Kaytee’s Exact Original Low Iron Maintenance Formula for Toucans, Mynas and other Softbills. A bowl of this is in the cage at all times and is supplemented with nuts, fruits and veggies like apples, papaya, grapes, oranges, peas and carrots and the occasional treat of small mice and insects like meal worms, crickets, megaworms, and waxworms are relished by the birds. Extra protein is essential if you want these birds to breed. Fresh water should always be provided. I use a shallow three to four inch deep, twelve inch wide crock the birds can drink from and bath in. The birds you are receiving from my aviaries are hand fed and closed banded. How recently they were weaned will affect how tame they are at first. -

S Largest Islands: Scenarios for the Role of Corvid Seed Dispersal

Received: 21 June 2017 | Accepted: 31 October 2017 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13041 RESEARCH ARTICLE Oak habitat recovery on California’s largest islands: Scenarios for the role of corvid seed dispersal Mario B. Pesendorfer1,2† | Christopher M. Baker3,4,5† | Martin Stringer6 | Eve McDonald-Madden6 | Michael Bode7 | A. Kathryn McEachern8 | Scott A. Morrison9 | T. Scott Sillett2 1Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA; 2Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, USA; 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia; 4School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 5CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Ecosciences Precinct, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 6School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 7ARC Centre for Excellence for Coral Reefs Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia; 8U.S. Geological Survey- Western Ecological Research Center, Channel Islands Field Station, Ventura, CA, USA and 9The Nature Conservancy, San Francisco, CA, USA Correspondence Mario B. Pesendorfer Abstract Email: [email protected] 1. Seed dispersal by birds is central to the passive restoration of many tree communi- Funding information ties. Reintroduction of extinct seed dispersers can therefore restore degraded for- The Nature Conservancy; Smithsonian ests and woodlands. To test this, we constructed a spatially explicit simulation Institution; U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Grant/Award Number: DEB-1256394; model, parameterized with field data, to consider the effect of different seed dis- Australian Reseach Council; Science and persal scenarios on the extent of oak populations. We applied the model to two Industry Endowment Fund of Australia islands in California’s Channel Islands National Park (USA), one of which has lost a Handling Editor: David Mateos Moreno key seed disperser. -

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty About the Past Against Uncertainty About the Future in Channel Islands National Park

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty about the Past against Uncertainty about the Future in Channel Islands National Park Scott A. Morrison Introduction Climate change threatens many species and ecosystems. It also challenges managers of protected areas to adapt traditional approaches for setting conservation goals, and the phil- osophical and policy framework they use to guide management decisions (Cole and Yung 2010). A growing literature discusses methods for structuring management decisions in the face of climate-related uncertainty and risk (e.g., Polasky et al. 2011). It is often unclear, how- ever, when managers should undertake such explicit decision-making processes. Given that not making a decision is actually a decision with potentially important implications, what should trigger management decision-making when threats are foreseeable but not yet mani- fest? Conservation planning for the island scrub-jay (Aphelocoma insularis) may warrant a near-term decision about non-traditional management interventions, and so presents a rare, specific case study in how managers assess uncertainty, risk, and urgency in the context of climate change. The jay is restricted to Santa Cruz Island, one of the five islands within Chan- nel Islands National Park (CINP) off the coast of southern California, USA. The species also once occurred on neighboring islands, though it is not known when or why those populations went extinct. The population currently appears to be stable, but concerns about long-term viability of jays on Santa Cruz Island have raised the question of whether a population of jays should be re-established on one of those neighboring islands, Santa Rosa. -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1. -

Reconstructing the Geographic Origin of the New World Jays

Neotropical Biodiversity ISSN: (Print) 2376-6808 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tneo20 Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays Sumudu W. Fernando, A. Townsend Peterson & Shou-Hsien Li To cite this article: Sumudu W. Fernando, A. Townsend Peterson & Shou-Hsien Li (2017) Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays, Neotropical Biodiversity, 3:1, 80-92, DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 05 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 956 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tneo20 Neotropical Biodiversity, 2017 Vol. 3, No. 1, 80–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays Sumudu W. Fernandoa* , A. Townsend Petersona and Shou-Hsien Lib aBiodiversity Institute and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA; bDepartment of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan (Received 23 August 2016; accepted 15 February 2017) We conducted a biogeographic analysis based on a dense phylogenetic hypothesis for the early branches of corvids, to assess geographic origin of the New World jay (NWJ) clade. We produced a multilocus phylogeny from sequences of three nuclear introns and three mitochondrial genes and included at least one species from each NWJ genus and 29 species representing the rest of the five corvid subfamilies in the analysis. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca Iridicyana Merida

THE PUZZLING VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN COLLARED JAY, CYANOLYCA VZRIDZCYANA MERIDA JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Previously, I have indicated (Kansas Sci. Bull., 42: 113, 1961) that the New World jays could be systematically grouped in two tribes on the basis of a variety of morphological and behavioral characteristics. I subsequently demonstrated (Occas. Papers Adams Ctr. Ecol. Studies, No. 11, 1964) the relationships between Cyanolyca and Aphelocoma. The tribe Aphelocomini, comprising the currently recognized genera Aphelocoma and Cyanolyca, may be characterized as follows: pattern and ornamen- tation of head simple, consisting of a dark mask, pale superciliary lineation, and no tendency for a crest; tail plain-tipped; vocal repertoire of one to three basic com- ponents, including alarm calls, flock-social calls, or both, that are nasal, querulous, and upwardly or doubly inflected. In contrast, the Cyanocoracini may be charac- tized as follows: pattern of head complex, consisting of triangular cheek patch, super- ciliary spot, and tendency for a crest; tail usually pale-tipped; vocal repertoire usu- ally complex, commonly including a downwardly inflected cuwing call and never an upwardly inflected, nasal querulous call (when repertoire is limited it almost always includes the cazo!ingcall). None of the four Mexican aphelocomine jays has more than three basic calls in its vocal repertoire. There are two exclusively South American species of CyanuZyca (C. viridicyana and C. pulchra). On the basis of the consistency with which the Mexican and Central American speciesof this genus hew to a general pattern of vocalizations as I described it for the tribe, I inferred (1964 op. -

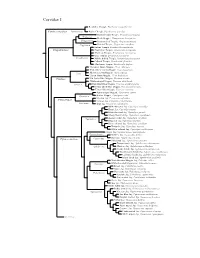

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus