02Founding Affidavit.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DIAZ EXPRESS (Pty) Ltd All Aboard the Diaz Express, a Fun Rail Experience in the Garden Route Region of South Africa

THE DIAZ EXPRESS (Pty) Ltd All aboard the Diaz Express, a fun rail experience in the Garden Route region of South Africa. Sit back and experience the lovely views over the Indian ocean, the river estuaries, the bridges, the tunnel, as the railway line meanders high above the seaside resorts and past the indigenous plant life of the Cape Floral Kingdom. The Diaz Express consists of three restored Wickham railcars, circa 1960, that operates on the existing Transnet Freight Rail infrastructure between George, the capital of the Southern Cape, and the seaside resort of Mossel Bay. With our variety of excursions we combine unsurpassed scenery, history, visits to quaint crafts shops and art galleries with gastronomic experiences par excellence!!! CONTACT US +27 (0) 82 450 7778 [email protected] www.diazexpress.co.za Reg No. 2014 / 241946 / 07 GEORGE AIRPORT SKIMMELKRANS STATION MAALGATE GREAT BRAK RIVER GLENTANA THE AMAZING RAILWAY LINE SEEPLAAS BETWEEN GEORGE AND MOSSEL BAY HARTENBOS MAP LEGEND Mossel Bay – Hartenbos shuttle Hartenbos – Glentana Lunch Excursion Hartenbos – Seeplaas Breakfast Excursion Great Brak – Maalgate Scenic Excursion PLEASE NOTE We also have a whole day excursion from Mossel Bay to to Maalgate, combining all of the above. MOSSEL BAY HARBOUR THE SEEPLAAS BREAKFAST RUN Right through the year (except the Dec school holiday) we depart from the Hartenbos station in Port Natal Ave (next to the restaurant “Dolf se Stasie”) at 09:00. Our destination is the boutique coffeeshop/art gallery Seeplaas where we enjoy a hearty breakfast at Seeplaas with stunning scenery and the artwork of Kenny Maloney. -

Dear Museum Friends Issue 7 of 201 the Museum Is Open Monday

July 2011 Phone 044-620-3338 Fax 044-620-3176 Email: [email protected] www.ourheritage.org.za www.greatbrakriver.co.za Editor3B Rene’ de Kock Dear Museum Friends Issue 7 of 201 The Museum is open Monday, Tuesday, Thursday The longest night for this year has passed and with it comes our longest news letter to date. and Friday between 9 am and Great Brak River and many other places have again been hard hit with storms and 4 pm and on bad weather and for the first time our Island in the river mouth has been really Wednesdays from and truly flooded. See report on www.ourheritage.org.za for more details. This 9.00 to 12.30 pm. web site is proving popular and we have already had nearly 5500 visits. Hopes next fund raising “Hands Nisde Mc Robert, our curator and Jan Nieuwoudt (BOC On” crafts member) attended this year’s museum heads annual workshop will be workshop and get together in Worcester and were in July and will be able to meet with amongst others Andrew Hall who is on Wednesday the new CEO of Heritage Western Cape. 20th. Subsequently, invited by Heritage Mossel Bay, Andrew was asked to be the keynote speaker at the Heritage Please call Hope de Mossel Bay AGM. Although very much in demand, Kock on during his two day visit Andrew was able to pay an 083 378 1232 extended visit to our museum. for full details and venue. More than seventy supporters of Heritage Mossel Bay attended the AGM which took place on the 22nd June and the past committee was re-elected for the April 2011- Short of a book March 2012 year. -

Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast

Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling Final May 2010 REPORT TITLE : Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling CLIENT : Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management PROJECT : Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast AUTHORS : D. Blake N. Chimboza REPORT STATUS : Final REPORT NUMBER : 769/2/1/2010 DATE : May 2010 APPROVED FOR : S. Imrie D. Blake Project Manager Task Leader This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Umvoto Africa. (2010). Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast. Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling. Prepared by Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd for the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management (May 2010). Phase 2: Eden DM Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd was appointed by the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP): Strategic Environmental Management division to undertake a sea level rise and flood risk assessment for a select disaster prone area along the Western Cape coast, namely the portion of coastline covered by the Eden District (DM) Municipality, from Witsand to Nature’s Valley. -

WC Covid 19.Town and Suburb Data. 23 October 2020. for Publication.Xlsx

Western Cape.COVID-19 cases.Town and Subrb data. -

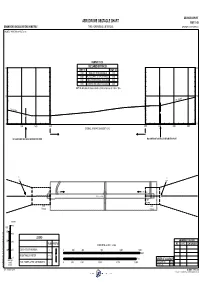

Aerodrome Obstacle Chart Rwy 11-29 Dimensions and Elevations in Metres Type a Operating Limitations George, South Africa Magnetic Variation 26° West (2015)

GEORGE AIRPORT AERODROME OBSTACLE CHART RWY 11-29 DIMENSIONS AND ELEVATIONS IN METRES TYPE A OPERATING LIMITATIONS GEORGE, SOUTH AFRICA MAGNETIC VARIATION 26° WEST (2015) RUNWAY 11-29 DECLARED DISTANCES 240 240 RWY 11 RWY 29 2000 TAKE-OFF RUN AVAILABLE 2120 2060 ACCELERATE-STOP DISTANCE 2120 2300 TAKE-OFF DISTANCE AVAILABLE 2500 2000 LANDING DISTANCE AVAILABLE 2000 RWY 29 declared distances include a starter extension of 120m x 45m. 210 210 OPE 1.2% SL 197.42 1.2% 29 SLOPE (!2 189.21 (!1 11 180 180 2600 2300 2000 2000 2300 2600 2900 OVERALL RUNWAY GRADIENT 1:245 0 0 NO SIGNIFICANT OBSTACLES BEYOND THIS POINT NO SIGNIFICANT OBSTACLES BEYOND THIS POINT (!1 (!2 197.1 202.9 190 114°M 294°M 197 11 .! 2000 x 45m ASPHALT 29 .! 60m Stopway 380m 300m Clearway Clearway METERS 120 FEET 300 90 LEGEND AMENDMENT RECORD 200 60 PLAN PROFILE NO DATE ENTERED BY HORIZONTAL SCALE 1:10 000 100 30 IDENTIFICATION NUMBER (!3 0200 400 800 1,200 1,600 Declared distances Meters HEIGHT AMSL IN METER 101.4 (!3 0 ORDER OF ACCURACY VERTICAL Feet SCALE POLE, TOWER, SPIRE, ANTENNA ETC. 5 0625 1,250 2,500 3,750 5,000 HORIZONTAL 5.0m 1:1000 VERTICAL 0.5m CHANGE: EFF: 10 NOV 2016 AD OBST TYPE A-01 Aerodrome information based on 2016 ACSA Survey data AERODROME CHART 34°00'24.13"S ELEV 648' GEORGE ATIS 126.225 GEORGE 022°22'27.41"E ALPHA OSCAR (APN) 122.65 FAGG TWR 118.90 APP 128.20 ELEV, ALT & HGT IN FEET NOTE CAUTION DIST IN METERS 1. -

Directorate: Planning & Integrated Services:– Enquiries

DIRECTORATE: PLANNING & INTEGRATED SERVICES:– ENQUIRIES GENERAL ENQUIRIES General enquiries from the public Ms Helené Bailey ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5073 TOWN PLANNING Enquiries regarding rezoning, departures, subdivisions, consent uses, relaxation of building lines, zoning certificates and removal of restrictive conditions Mr B Ndwandwe ..................................................................................................................................................................5077 Ms O Louw ...........................................................................................................................................................................5074 Intern ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6290 Enquiries regarding amendment of structure plan, amendment of urban edge, SDF, flood lines, availability of municipal properties and erven Mr J Roux …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….5071 Enquiries regarding application forms, erven sizes, erven dimensions, locality plans, SG-diagrams, maps (Office hours: 08H00-13H00 and 14H00-15H00) Ms D Truter 5075 Ms D Seconds 5247 Ms L Koen 5166 BUILDING CONTROL – SUBMISSION OF BUILDING PLANS (Office hours: 08H00-13H00 and 14H00-15H00) Enquiries regarding application forms, demolition permits, submission of building plans, copies of building plans Ms D Seconds 5247 Ms L Koen 5166 Ms D Truter 5075 BUILDING CONTROL – PROGRESS AND APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS Progress of submitted building plans (Enquiries from 7:45 to 10:00) -

WC043 Mossel

PREFACE The Constitution obliges all spheres of Government to respect, protect, promote and fulfill the rights contained in the Bill of Rights of South Africa. The key focus areas (priority objectives) of Mossel Bay Municipality are as follows: 1) Democratic and accountable governance; 2) Provision of services in a sustainable manner; 3) Promote social and economic development; 4) Safe and healthy environment; and 5) Public participation (community development) Through these key focus areas outlined in the IDP, we must intervene and focus our resources in order to achieve our goals. The Constitution compels municipalities to strive, within their financial and administrative capacity, to achieve these objectives. Local Government is the closest sphere to the communities and therefore has a key role in the delivering of basic services and to enhance the development of its communities. As derived in the previous revision of the IDP, this document is a strategic plan to help us set out our budget priorities. At the recent public participation workshops residents indicated maintenance of roads, low and middle income housing, community safety, mobile police stations, storm water, sewerage, clinics and unemployment as the key priorities. TABLE OF CONTENT Page FOREWORD OF THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR 1 FOREWORD OF THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER 2 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 3 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Governance Structure 1.2 Strategic and Administrative objectives 1.3 Institutional Capacity summary and Human Resource Development 1.4 The Integrated Development -

Status Quo Assessment Final

REVIEW OF THE AIR QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN STATUS QUO ASSESSMENT and MUNICIPAL RESOURCES Progress Report No. GRDM-2019 PR.2 Final Report May 2019 COMPILED BY GRDM AQMP Status Quo Assessment Page 1 of 39 May 2019 Progress Report No. GRDM-2019 PR.2 Final Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1: ............................................................................................................................... 5 STATUS QUO ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................. 5 1 GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHICS AND CLIMATE .................................................. 6 1.1 BITOU ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 KNYSNA ............................................................................................................... 10 1.3 GEORGE ............................................................................................................... 12 1.4 MOSSEL BAY ...................................................................................................... 14 1.5 HESSEQUA ........................................................................................................... 16 1.6 KANNALAND ...................................................................................................... 18 1.7 OUDTSHOORN ................................................................................................... -

Mossel Bay Municipality Idp Budget & Pms Representative Forum 20 May 2021

MOSSEL BAY MUNICIPALITY IDP BUDGET & PMS REPRESENTATIVE FORUM 20 MAY 2021 DRAFT IDP & BUDGETPUBLIC CONSULTATION • NO PHYSICAL PUBLIC MEETINGS: Limit risk of spreading Covid19 • INPUT SUBMISSION: DUE 30 APRIL 2021 • Email to [email protected] (IDP Related) OR [email protected] (Budget related) • Hand deliver written submissions to 101 Marsh Street • Post to: Private Bag X29, Mossel Bay, 6500 • Facebook live ward based Schedule: FACEBOOK LIVE: IDP & BUDGET CONSULTATION SCHEDULE DATE: APRIL 2021 DAY TIME WARD 07 Wednesday 18:00 6 & 8 08 Thursday 18:00 7 12 Monday 18:00 9 13 Tuesday 18:00 10 14 Wednesday 18:00 11 15 Thursday 18:00 12 19 Monday 18:00 13 20 Tuesday 18:00 14 21 Wednesday 18:00 1,2, & 3 22 Thursday 18:00 4 & 5 2020/2021 MID TERM PERFORMANCE Municipal Financial Corporate Community Planning and Infrastructure Manager Services Services Services Economic Services Development BUDGET OVERVIEW 2021-2022 BUDGET [VALUE] [PERCENTAGE] [VALUE] [PERCENTAGE] Operating Capital 2020-2021 Adj 2021-2022 % Increase / % of Total BUDGET BUDGET (Decrease) R 1 289 617 231 R 1 363 936 094 5.8 85.0 R 252 928 080 R 241 084 372 -4.7 15.0 R 1 542 545 311 R 1 605 020 466 4.1 100.0 21/22 MTREF DRAFT CAPITAL BUDGET – PER SOURCE FUNDING SOURCE 2021/2022 % of TOTAL BUDGET Capital Replacement Reserve (Internal) R 122 566 591 50.8% Municipal Infrastructure Grant R 21 980 000 9.1% Development of Sport & Recreation R 265 217 0.1% Facility Grant Integrated National Electrification R 8 718 261 3.6% Programme Department of Human Settlement R 53 913 043 22.4% -

Western Cape COVID-19 Cases at Town and Suburb Level.1 January

Western Cape COVID-19 at Town and Suburb levels. -

The Garden Route Golfscape: a Golfing Destination in the Rough

THE GARDEN ROUTE GOLFSCAPE: A GOLFING DESTINATION IN THE ROUGH LOUISE-MARI VAN ZYL Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Mr. BH Schloms December 2006 ii DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: iii SUMMARY The Garden Route is located along the southern Cape coast of South Africa, between the Outeniqua Mountain Range and the coast, stretching from Gourits River in the west to Bloukranz River in the east. This region is recognised as a holiday destination and the centre of the southern Cape’s tourism industry. It has also gained popularity as a golfing destination set to proliferate in terms of new golf- course developments (Golf Digest 2004; Gould 2004; Granger 2003). No known complete academic or public record is however available for the study area in which all the golf development types, namely short courses, public-municipal golf-courses and residential golf estates, are recorded. This leaves a gap in the understanding of the Garden Route as a golfing destination, as well as opening the floor for public speculation about the status of the Garden Route golfscape. This situation emphasises the need for a description of the Garden Route golfscape in order to achieve a better understanding of it and of the Garden Route as an emerging golfing destination. The research aspires to describe the Garden Route golfscape in terms of the geographic spatial distribution and characteristics of all the golf development types mentioned. -

Botanical Impact Assessment

BOTANICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT RENSBURG ESTATE 137 PROPERTY AT GROOT-BRAKRIVIER, MOSSEL BAY January 2020 Mark Berry Environmental Consultants Pr Sci Nat (reg. no. 400073/98) Tel: 083 286-9470 Fax: 086 759-1908 E-mail: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………………………..2 2 PROPOSED PROJECT……………………………………………………………………………………..2 3 TERMS OF REFERENCE…………………………………………………………………………………..4 4 METHODOLOGY…………………………………………………………………………………………….5 5 LIMITATIONS TO THE STUDY……………………………………………………….……………………5 6 LOCALITY & BRIEF SITE DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................... 6 7 BIOGEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT ..................................................................................................... 6 8 VEGETATION & FLORA .................................................................................................................. 7 9 CONSERVATION STATUS & BIODIVERSITY NETWORK........................................................... 14 10 IMPACT ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 15 11 SUMMARY & CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................... 17 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPENDICES CV OF SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 2 1 INTRODUCTION This report investigates the botanical