State's Brief on Defendant's Intention to Call Joyette Holmes As a Witness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

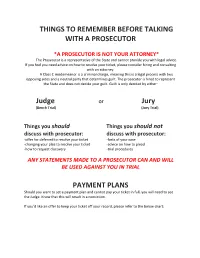

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

The Prosecutor, the Term “Prosecutorial Miscon- Would Clearly Fall Within a Layperson’S Definition of Prose- Duct” Unfairly Stigmatizes That Prosecutor

The P ROSECUTOR Measuring Prosecutorial Actions An Analysis of Misconduct versus Error B Y S HAWN E. MINIHAN Rampant Prosecutorial Misconduct The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2014 The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, And The System That Protects Them The Huffington Post, Aug. 5, 2013 Misconduct by Prosecutors, Once Again The New York Times, Aug. 13, 2012 22 O CTOBER / NOVEMBER / DECEMBER / 2014 P ROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT has become nation- in cases where such a perception is entirely unwarranted… .”11 al news. To a layperson, the term “prosecutorial miscon- The danger inherent in the court’s overbroad use of the duct” expresses “intentional wrongdoing,” or a “deliberate term “prosecutorial misconduct” is twofold. First, in cases violation of a law or standard” by a prosecutor.1 where there is an innocent mistake or poor judgment on The newspaper articles cited at left describe acts that the part of the prosecutor, the term “prosecutorial miscon- would clearly fall within a layperson’s definition of prose- duct” unfairly stigmatizes that prosecutor. A layperson may cutorial misconduct. For example, the article “Rampant assume that the prosecutor intentionally committed a Prosecutorial Misconduct” discusses United States v. Olsen, wrongdoing or deliberately violated a law or ethical stan- where federal prosecutors withheld a report that revealed dard. sloppy work on the part of the government’s forensic sci- In those cases where the prosecutor has, in fact, commit- entists, resulting in wrongful convictions.2, 3 The article ted misconduct, the term “prosecutorial misconduct” may “The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, not impose a harsh enough degree of stigmatization. -

The Role of the Prosecutor: Serving the Interests of All the People

V INE.2PPR 03/14/01 10:33 AM THE ROLE OF THE PROSECUTOR: SERVING THE INTERESTS OF ALL THE PEOPLE Alan Vinegrad* The legal profession’s conception of public interest work has tradi- tionally focused on the work of pro bono or civil liberties-based organi- zations, such as the American Civil Liberties Union and its local chapters, a variety of legal defense funds, the Legal Aid Society, and other similar organizations. Certain law schools provide financial incentives and insti- tutional support designed to actively encourage their students to pursue job opportunities with these groups. Many students—the author in- cluded—can easily spend three years at a law school and not have any notion that public interest work also includes the job of being an Assistant District Attorney (local prosecutor), an Assistant Attorney General (state prosecutor), or an Assistant United States Attorney (federal prosecutor). Many others, aware of the general role of the prosecutor in our legal system, nevertheless have been steeped in publicity in recent years about the rather unique and increasingly politicized work of our most prominent prosecutors—the special prosecutors appointed under the now defunct Independent Counsel statute.1 From this publicity, one can easily draw incomplete, if not unfair, judgments about what it means to be a prose- cutor in our society. It did not occur to me until well into my legal career that my own notion of public interest work was under-inclusive in this one significant respect: it did not include the work of the tens of thousands of federal, state, and local prosecutors across the country who lead the legal fight against crime and protect our society and its citizens from those who seek to enrich themselves at society’s expense. -

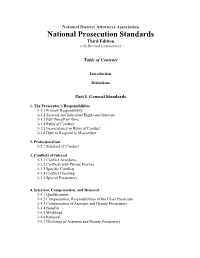

National Prosecution Standards, Third Edition Updated 2009

National District Attorneys Association National Prosecution Standards Third Edition with Revised Commentary Table of Contents Introduction Definitions Part I. General Standards 1. The Prosecutor’s Responsibilities 1-1.1 Primary Responsibility 1-1.2 Societal and Individual Rights and Interests 1-1.3 Full-Time/Part-Time 1-1.4 Rules of Conduct 1-1.5 Inconsistency in Rules of Conduct 1-1.6 Duty to Respond to Misconduct 2. Professionalism 1-2.1 Standard of Conduct 3. Conflicts of Interest 1-3.1 Conflict Avoidance 1-3.2 Conflicts with Private Practice 1-3.3 Specific Conflicts 1-3.4 Conflict Handling 1-3.5 Special Prosecutors 4. Selection, Compensation, and Removal 1-4.1 Qualifications 1-4.2 Compensation; Responsibilities of the Chief Prosecutor 1-4.3 Compensation of Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 1-4.4 Benefits 1-4.5 Workload 1-4.6 Removal 1-4.7 Discharge of Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 5. Staffing and Training 1-5.1 Transitional Cooperation 1-5.2 Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 1-5.3 Orientation and Continuing Legal Education 1-5.4 Office Policies and Procedures 6. Prosecutorial Immunity 1-6.1 Scope of Immunity Part II. Relations 1. Relations with Local Organizations 2-1.1 Chief Prosecutor’s Involvement 2-1.2 Information Input 2-1.3 Organization Establishment 2-1.4 Community Prosecution 2-1.5 Enhancing Prosecution 2. Relations with State Criminal Justice Organizations 2-2.1 Need for State Association 2-2.2 Enhancing Prosecution 3. Relations with National Criminal Justice Organizations 2-3.1 Enhancing Prosecution 2-3.2 Prosecutorial Input 4. -

The American Prosecutor in Historical Context

The American Prosecutor in Historical Context By Joan E. Jacoby This is the second of two articles detailing the development of the office of the American prosecutor. The first part appeared in the March/April issue of the magazine. For this reason, the endnotes begin with number 32, where they left off in the first part of the article. The American Prosecutor From Appointive to Elective Status This section examines the democratic movement during the period from 1789 to the Civil War that changed the local prosecutor from an appointed to an elected official. In these early days of the new republic, the country shifted from a limited democracy that was ruled by a few franchised citizens to a democracy that extended the vote to almost all citizens. At the same time, governing power continued to be decentralized as the state’s influence over local authority declined and weakened. With the power of the vote and the election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828, more and more offices became elective. As Jacksonian democracy swept the land, sparked by the spirit of independence in the new states, two important changes occurred. The position of the local judge changed from appointed to elected, which in turn directly helped make the office of the local prosecutor elective as well. A separation of powers occurred that moved the prosecutor from the judicial branch of government to the executive. These two changes gave the American prosecutor a new set of responsibilities, power and authority. Ultimately they became the foundation for the independent discretionary authority that was to distinguish this office from that of any other prosecutor in any country in the world. -

The Federal Prosecutor by ROBERT H

[VoL. 24 18 JouRNAL oP niE AMERICAN JuDICATURE SociETY The Federal Prosecutor BY ROBERT H. JACKSON* "The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which mark a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway." It would probably be within the range of that ate of the United States. You are thus required exaggeration permitted in Washington to aay to win ·an expression of confidence in your char that assembled in this room is one of the most acter by both the legislative and the executive powerful peace-time forces known to our coun branches P.f the government before assuming try. The prosecutor has more control over life, the responsibilities of a federal prosecutor. liberty, and reputation than any other person in Your responsibility in your several districts America. His discretion is tremendous. He for law enforcement and for its methods can can have citizens investigated and, if he is that not be wholly surrendered to Washington, and kind of person, he can have this done to the tu~e ought not to be assumed by a centralized de of public statements and veiled or unveiled in partment of justice. It is an unusual and rare timations. Or the prosecutor may choose a instance in which the local district attorney more subtle course and simply have a citizen's should be superseded in the ha~dling of litiga friends interviewed. The prosecutor can order tion, except where be requests help of Wash arrests, present cases to the grand· jury in se ington. -

Opening Statement 4. Prosecutor 2 – Direct of Dana Capro 5. P

ROLES TO ASSIGN 1. Judge 2. Courtroom Deputy 3. Prosecutor 1 – opening statement 4. Prosecutor 2 – direct of Dana Capro 5. Prosecutor 3 – direct of Jamie Medina 6. Prosecutor 4 – cross of Pat Morton 7. Prosecutor 5 – cross of J.D. Morton 8. Prosecutor 6 – closing argument 9. Defense attorney 1 – opening statement 10. Defense attorney 2 – cross of Dana Capro 11. Defense attorney 3 – cross of Jamie Medina 12. Defense attorney 4 – direct of Pat Morton 13. Defense attorney 5 – direct of J.D. Morton 14. Defense attorney 6 – closing argument 15. Dana Capro 16. Jamie Medina 17. Pat Morton 18. J.D. Morton Theft in the 1st degree occurs when a person wrongfully obtains unauthorized control over the property of another with intent to deprive the owner of that property, and the value of the property is more than $1,500. 1 United States of America v. Pat Morton1 Courtroom Deputy: (bang gavel) All rise, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington is now in session, the Honorable __________ presiding. Judge (walk to judge’s bench and sit): Please be seated. Before we begin, I will ask the courtroom deputy to administer the oath to the jurors. Courtroom Deputy: Would the jurors please rise and raise your right hand. DO YOU AND EACH OF YOU SOLEMNLY SWEAR THAT THE ANSWERS YOU SHALL GIVE TO THE QUESTIONS ASKED BY THE COURT, TOUCHING UPON YOUR QUALIFICATIONS TO ACT AS JURORS IN THE CAUSE NOW BEFORE THE COURT, SHALL BE THE TRUTH, THE WHOLE TRUTH, AND NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH? Jurors: I do. -

Sizing up the Prosecution a Quick Guide to Local Prosecution

SIZING UP THE PROSECUTION A QUICK GUIDE TO LOCAL PROSECUTION Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest Advising 2010 Edition: Harvard Law School Lisa D. Williams, Esq. Pound 329 Associate Director for J.D. Advising 1563 Massachusetts Avenue Iris Hsiao Cambridge, MA 02138 Summer Fellow (617) 495-3108 Fax: (617) 496-4944 2007 Edition: Lisa D. Williams, Esq. © 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College Assistant Director for J.D. Advising Andrew Chan Summer Fellow; Current 1L at HLS 1997 Edition: Carolyn Stafford Stein, Esq. Assistant Director for Alumni Advising Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: WHY PROSECUTION? ......................................................................................... 3 DIFFERENCES AMONG FEDERAL, STATE, AND LOCAL PROSECUTING OFFICES . 3 WHAT A LOCAL PROSECUTOR DOES ................................................................................................. 5 DECIDING TO BECOME A PROSECUTOR ........................................................................................ 6 CHOOSING THE RIGHT OFFICE .......................................................................................................... 8 APPLYING TO BECOME A PROSECUTOR .................................................................................... 111 BACKGROUND CHECK ............................................................................................................................. 14 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................. -

Judicial Review: Appeals and Postconviction Proceedings –

Judicial Review: Appeals and Postconviction Proceedings Nancy J. King Judicial review has provided at best an incomplete remedy for individuals convicted of crimes they did not commit. In a groundbreaking study, Professor Brandon Garrett (2011) examined whether and how judicial remedies helped 250 of the first DNA exonerees. By tracking these wrongfully convicted individuals’ attempts to challenge their convictions in the courts before they obtained the DNA test results that ultimately led to their exonerations, his study provides a glimpse of what judicial review offers the wrongfully convicted who lack DNA evidence to prove their innocence. Of those who challenged their non-capital convictions, more than 90% failed — a success rate not significantly different from that of judicial challenges brought by similar defendants convicted of similar crimes who were not exonerated. Those who succeeded in securing a judicial order reversing their initial convictions often faced continued prosecution. Garrett’s research “demonstrates that normal legal mechanisms were incapable of detecting innocence in these (now indisputable) innocence cases” (Aronson & Cole, 2009, p. 614). In another study comparing the cases of 260 defendants exonerated after conviction for committing violent felonies with the cases of 200 similar defendants who avoided conviction, Professor Jon Gould and his colleagues also noted that most of the wrongfully convicted individuals were freed only after action by prosecutors and pardoning authorities (Gould, Carrano, Leo, & Young, 2013a, p. 22). Judicial review may have played an indirect role in these exonerations by attracting the attention of advocates who helped to collect and present new evidence of innocence. Only rarely, however, did the judicial system correct its own mistakes.