The Police-Prosecutor Relationship and the No-Contact Rule: Conflicting Incentives After Montejo V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle School and High School Lesson Plan on the Sixth Amendment

AMERICAN CONSTITUTION SOCIETY (ACS) CONSTITUTION IN THE CLASSROOM SIXTH AMENDMENT RIGHT TO COUNSEL MIDDLE & HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM — SPRING 2013 Lesson Plan Overview Note: times are approximate. You may or may not be able to complete within the class period. Be flexible and plan ahead — know which activities to shorten/skip if you are running short on time and have extra activities planned in case you move through the curriculum too quickly. 1. Introduction & Background (3-5 min.) .................................................. 1 2. Hypo 1: The Case of Jasper Madison (10-15 min.) ................................ 1 3. Pre-Quiz (3-5 min.) ................................................................................. 3 4. Sixth Amendment Text & Explanation (5 min.) ..................................... 4 5. Class Debate (20 min.) ........................................................................... 5 6. Wrap-up/Review (5 min.)....................................................................... 6 Handouts: Handout 1: State v. Jasper Madison ........................................................... 7 Handout 2: Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution .............. 8 Handout 3: Franklin Adams’s Disciplinary Hearing ..................................... 9 Handout 4: The Case of Gerald Gault ....................................................... 10 Before the lesson: Ask the teacher if there is a seating chart available. Also ask what the students already know about the Constitution as this will affect the lesson -

The Role of Lawyers in Producing the Rule of Law: Some Critical Reflections*

The Role of Lawyers in Producing the Rule of Law: Some Critical Reflections* Robert W Gordon** INTRODUCTION For the last fifteen years, American and European governments, lending institutions led by the World Bank, and NGOs like the American Bar Association have been funding projects to promote the "Rule of Law" in developing countries, former Communist and military dictatorships, and China. The Rule of Law is of course a very capacious concept, which means many different things to its different promoters. Anyone who sets out to investigate its content will soon find himself in a snowstorm of competing definitions. Its barebones content ("formal legality") is that of a regime of rules, announced in advance, which are predictably and effectively applied to all they address, including the rulers who promulgate them - formal rules that tell people how the state will deploy coercive force and enable them to plan their affairs accordingly. The slightly-more-than barebones version adds: "applied equally to everyone."' This minimalist version of the Rule of Law, which we might call pure positivist legalism, is not, however, what the governments, multilateral * This Article is based on the second Annual Cegla Lecture on Legal Theory, delivered at Tel Aviv University Faculty of Law on April 23, 2009. ** Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University. I am indebted to the University of Tel Aviv faculty for their generous hospitality and helpful comments, and especially to Assaf Likhovski, Roy Kreitner, Ron Harris, Hanoch Dagan, Daphna Hacker, David Schorr, Daphne Barak-Erez and Michael Zakim. 1 See generallyBRIAN TAMANAHA, ON THE RULE OF LAW: HISTORY, POLITICS, THEORY 26-91 (2004) (providing a lucid inventory of the various common meanings of the phrase). -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

A Brief History of the Federal Magistrate Judges Program

A Brief History of the Federal Magistrate Judges Program he federal Magistrate Judges system judicial officers, to order the arrest, detention, and release of 1 is one of the most successful judicial federal criminal offenders. Four years later, drawing on the English and colonial tradition of local magistrates and justices Treforms ever undertaken in the fed- of the peace serving as committing officers, Congress autho- eral courts. Once the Federal Magistrates Act rized the new federal circuit courts to appoint “discreet persons learned in the law” to accept bail in federal criminal cases.2 was enacted in 1968, the federal judiciary rap- These discreet persons were later called circuit court com- idly implemented the legislation and estab- missioners and given a host of additional duties throughout the th lished a nationwide system of new, upgraded 19 century, including the power to issue arrest and search warrants and to hold persons for trial. They were compensated judicial officers in every U.S. district court. It for their services on a fee basis.3 then methodically improved and enhanced In 1896, Congress reconstituted the commissioner system. It adopted the title U.S. Commissioner, established a four-year the system over the course of the next several term of office, and provided for appointment and removal by decades. As a result, today’s Magistrate Judge the district courts rather than the circuit courts.4 No minimum qualifications for commissioners were specified and no limits system is an integral and highly effective com- imposed on the number of commissioners the courts could ponent of the district courts. -

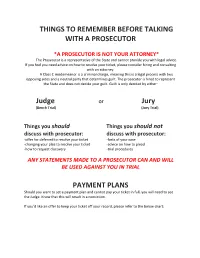

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

49 Tips for the New Lawyer ©Attorney at Work

TIPS FOR THE 49 NEW LAWYER attorneyatwork 49 Tips for the New Lawyer By Merrilyn Astin Tarlton This is not going to be easy. But you knew that well before you passed the bar. (Congratulations, by the way!) There are a lot of lessons you will need to learn the hard way. Still. It would be nice, wouldn’t it, to have a slight edge when starting out as a new lawyer? Perhaps an older, savvier friend to fill you in on subtler codes of conduct or to introduce you to the court clerk. Someone to grab you by the elbow and steer you away from trouble and toward better decisions. Or even a cranky old guy to “teach you a thing or two.” We think so, too. So consider this list of tips and truths your friendly kick to the shins under the conference table and, in some cases, a not-so-subtle kick in the pants. We’ve compiled “49 Tips for the New Lawyer” to help you get out of the blocks with the best start possible. Whether you’re backed up by an army of support staff and senior partners or valiantly braving it solo, soak up some of this sound advice and see if it doesn’t help the hard lessons hit a little softer. (Psssst. You’ll find more than just 49 great tips here — there are also 128 links to some of Attorney at Work’s most popular posts.) Merrilyn Astin Tarlton is a founding member of the Legal Marketing Association, past Trustee and President of the College of Law Practice Management and recipient of the LMA Hall of Fame award. -

The Lawyer As Counselor by Jack W

The Lawyer As Counselor by Jack W. Burtch Jr. In my second year of law school, I began working for a well-known Nashville defense lawyer. He was in his early sixties then, as I am now. One day he said, “JB, I want you to go to the county health department, find all the pamphlets on mental health, and bring them back here.” Thinking this was somewhat unusual, I asked the reason for his request. “Because many of my clients have trouble accepting real - ity,” he said, “and I want to find out why.” Sometimes simply bringing clients into reality is our job. When I look at my law license with its faded friends, and they strongly suggested I come and signatures, I see the words “Attorney and talk to you.” I didn’t know why he was calling Counsellor at Law.” For many years, only that first either, but I was certainly intrigued. And after we word registered. I was a lawyer. That meant I rep - had chatted for about half an hour, I started to see resented clients in their causes. Within the the picture. Here was a successful executive in a bounds of morality and legality, I helped them large organization who was being nudged toward achieve their goals by zealous advocacy. I listened the sidelines. To me, the signs were obvious: more to what they wanted and tried to make it happen responsibility for “special” projects; less line for them. accountability; exclusion from meetings he once Yet as the years went by, I began to notice led; less informal interaction with top manage - something unexpected. -

The Prosecutor, the Term “Prosecutorial Miscon- Would Clearly Fall Within a Layperson’S Definition of Prose- Duct” Unfairly Stigmatizes That Prosecutor

The P ROSECUTOR Measuring Prosecutorial Actions An Analysis of Misconduct versus Error B Y S HAWN E. MINIHAN Rampant Prosecutorial Misconduct The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2014 The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, And The System That Protects Them The Huffington Post, Aug. 5, 2013 Misconduct by Prosecutors, Once Again The New York Times, Aug. 13, 2012 22 O CTOBER / NOVEMBER / DECEMBER / 2014 P ROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT has become nation- in cases where such a perception is entirely unwarranted… .”11 al news. To a layperson, the term “prosecutorial miscon- The danger inherent in the court’s overbroad use of the duct” expresses “intentional wrongdoing,” or a “deliberate term “prosecutorial misconduct” is twofold. First, in cases violation of a law or standard” by a prosecutor.1 where there is an innocent mistake or poor judgment on The newspaper articles cited at left describe acts that the part of the prosecutor, the term “prosecutorial miscon- would clearly fall within a layperson’s definition of prose- duct” unfairly stigmatizes that prosecutor. A layperson may cutorial misconduct. For example, the article “Rampant assume that the prosecutor intentionally committed a Prosecutorial Misconduct” discusses United States v. Olsen, wrongdoing or deliberately violated a law or ethical stan- where federal prosecutors withheld a report that revealed dard. sloppy work on the part of the government’s forensic sci- In those cases where the prosecutor has, in fact, commit- entists, resulting in wrongful convictions.2, 3 The article ted misconduct, the term “prosecutorial misconduct” may “The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, not impose a harsh enough degree of stigmatization. -

The Rule of Law How Do We Preserve It in the Modern Age?

the rule of law How Do We Preserve It in the Modern Age? CBA President Jonathan M. Shapiro welcoming event attendees. It seems too often today we see the Rule of Law attacked and criticized. When a judge makes a decision that is unpopular, even if well-reasoned, it may be assailed as motivated by other factors. The media is criticized as distributing “fake news” and as biased. Social media does not apply the same journalistic standards as traditional media, and we have seen public opinion manipulated through social media. Connecticut has a re- quirement that all high school graduates must earn half a credit of civics education, but is that enough to instill civic principles in the public? By Alysha Adamo and Leanna Zwiebel 12 Connecticut Lawyer January/February 2019 Visit www.ctbar.org “Politics and the Rule of Law” panelists (L to R) Hon. Ingrid L. Moll, Hon. William H. Bright, Jr., Secretary of the State Denise W. Merrill, State Representative Matthew D. Ritter, State Representative Thomas P. O’Dea, Jr., State Representative Steven J. Stafstrom, and Kelley Galica Peck. Connecticut Supreme Court Chief “The Rule of Law: Ensuring the Future” panelists (L to R) CBA President Jonathan M. Shapiro Justice Richard A. Robinson provid- Justice Maria Araujo Kahn, Chief Justice Richard A. introducing Connecticut Supreme Court ing the event’s welcome remarks. Robinson, Hon. Douglas S. Lavine, and Hon. Ingrid L. Moll. Chief Justice Richard A. Robinson. (L to R) Justice Andrew J. McDonald; CBA President Jonathan M. Shapiro; Steven Hernández of the Commission on Women, Children and Seniors; Hon.