A Guide to Landing a Job in a Prosecutor S Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of the Office of District Attorney

AN OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF DISTRICT ATTORNEY I. GENERAL INFORMATION FOR DISTRICT ATTORNEYS A. Authority 1. Louisiana Constitution Art. 5 Section 26 (B) Powers. Except as otherwise provided by this constitution, a district attor- ney, or his designated assistant, shall have charge of every criminal prosecu- tion by the state in his district, be the representation of the state before the grand jury in his district, and be the legal advisor of the grand jury. He shall perform other duties provided by law. 2. See also Code of Criminal Procedure Articles 61-66. The district attorney determines whom, when, and how to charge a State criminal law violation. Law enforcement agencies report to the district attor- ney on arrests made. He then evaluates (screening) each case based on the weight and admissibility of evidence in consideration of his greater burden of proof of guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” His obligation is to seek justice rather than merely to convict. 3. Other statutory authority. There are numerous statutes authorizing the district attorney to enforce certain laws. Examples are enforcement of election code matters and open meeting requirements. B. DUTIES AND FUNCTIONS 1. Criminal Duties a. Receive, data entry (case management system) and review(screen) all post arrest criminal files submitted for prosecution by local, parish, state and federal law enforcement agencies to determine the nature of the charges(probable cause for arrest) and weight of evidence for prosecution and to take one or more of the following actions: (1) If accepting or amending submitted charges, prepare bills of information. (2) If accepting charges but defendant qualifies for diversion, refer to diversion program (PTI). -

Jeffrey Brown

Jeffrey A. Brown Partner New York | Three Bryant Park, 1095 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY, United States of America 10036-6797 T +1 212 698 3511 | F +1 212 698 3599 [email protected] Services Litigation > White Collar, Compliance and Investigations > Anti-Corruption Compliance and Investigations > Asset Management Litigation/Enforcement > Automotive and Transportation > Banking and Financial Institutions > Jeffrey A. Brown focuses his practice on white collar defense, securities litigation, SEC and CFTC enforcement actions, and related commercial litigation. His experience includes conducting internal investigations across multiple industries and across international boundaries, representing companies and individuals in connection with investigations by the Department of Justice, the Securities Exchange Commission, and state and local prosecutors. Mr. Brown’s practice includes a number of matters representing individuals investigated for “spoofing” and other market manipulation in markets for various commodities. Mr. Brown previously worked for approximately 9 years at the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, where he served as Co-Chief of the General Crimes Unit and before that as Acting Deputy Chief of the Narcotics Unit. As an Assistant U.S. Attorney, Mr. Brown investigated and prosecuted crimes in the Terrorism, International Narcotics Trafficking, Narcotics, Violent Crimes and General Crimes Units. Many of Mr. Brown’s representations at Dechert involve investigations brought by his former Office. The recipient of the 2011 Attorney General’s Distinguished Service Award, during his time at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, he prosecuted several high-profile cases, including United States v. Faisal Shahzad, the Times Square bomber, and United States v. -

Product Retrieval Procedures

PRODUCT RETRIEVAL PROCEDURES X-1 INDEX PAGE Overview 3 Analysis of FDA Recall Guidelines 4 A Product Retrieval Blueprint for Action 11 Food & Drug Regulations Title 21, Chapter 1 32 Subchapter A, Parts 7, 7.1 through 7.49 Method for Conducting Retrieval Effectiveness Checks 46 Published by Food and Drug Administration Example -- Corporate Retrieval Program 56 X-2 FOOD AND DRUG RECALL GUIDELINES OVERVIEW The regulations set forth in the Federal Register on June 16, 1978, established the following facts: 1. If an emergency of retrieval arises, it is the responsibility of a manufacturer or distributor to initiate voluntarily and carry out a retrieval of its product that is found to be in violation of the Food and Drug Act. 2. The retrieval must be initiated when the manufacturer discovers or is informed of the infraction. 3. The burden in carrying out a retrieval is totally that of a manufacturer or distributor. 4. Although a retrieval will be conducted by a manufacturer or distributor, it must be carried out to satisfaction of the FDA. To be able to conduct a product retrieval to the satisfaction of the FDA, the following preparation and conditions are essential: 1. An established contingency plan. 2. Assigned responsibility and authority to specific management personnel to carry out the contingency plan. 3. A thorough understanding of the regulation guidelines on retrieval. 4. Recognition of the urgency that FDA places on effectiveness, promptness and thoroughness. 5. Accurate documentation of ingredient and materials used. 6. Accurate documentation of distribution of products. 7. Accurate coding. The proof of effectiveness can only be learned through Trial Runs. -

Hiring Practices of California District

HIRING PRACTICES OF CALIFORNIA DISTRICT ATTORNEY OFFICES 2017-2018 County Map of California 2 3 California District Attorney Office Hiring Practices INTRODUCTION This directory was compiled by the UC Davis School of Law in the Spring of 2017. It contains information about student and attorney positions at district attorney offices throughout California. This information is based on entries in an earlier directory, previous job listings, web site information, and follow-up telephone calls. Some counties conduct on campus interviews for third year students or both second and third year students at several law schools in the fall. The UC Davis School of Law will advertise these opportunities. Please note that you should always verify the names of any hiring attorney or District Attorney, and the office address, before corresponding with these offices. Before any interview, you should research each particular office and the background of the District Attorney. Also, hiring practices can change at any time due to changes in budgets and turnover. If you are particularly interested in a county, it is recommended that you contact the representative listed, the district attorney office, or the county’s personnel office directly to determine hiring needs. The vast majority of the offices are very helpful and willing to provide necessary information to those who are interested. Another great resource for finding employment opportunities in prosecution is the California District Attorneys’ Association website. The association’s web address is www.cdaa.org. Good luck! 4 Table of Contents Alameda ................................................. 4 Placer ..................................................... 25 Alpine ..................................................... 5 Plumas .................................................... 25 Amador .................................................. 5 Riverside ...................................................26 Butte ....................................................... 5 Sacramento ............................................ -

Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: a Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-To-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Brownlee, Katelyn Elizabeth, "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1597 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee entitled "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Michelle Violanti, Major Professor We have read this thesis -

The Office” Sample Script

“THE OFFICE” SAMPLE SCRIPT “The Masseuse” by John Chang [email protected] FADE IN: INT. OFFICE – MORNING MICHAEL enters and stops by PAM’S desk. MICHAEL Morning, Pam. Did you catch the ‘L Word’ last night? PAM No. I missed it. MICHAEL It was a great episode. Tim found out that Jenny was cheating on him with Marina, and Dana and Lara broke up. But the whole thing was totally unbelievable. PAM Why? MICHAEL Because. There’s no way that lesbians are that hot in real life. I know that we all have our fantasies about a pair of hot lesbian chicks making out with each other, but that’s just not how it is in the real world. PAM Um, o-kay. MICHAEL I mean, seriously, Pam. There’s no way in a million years that a smoking hot lesbian babe would come up to you and ask you out on a date. It just wouldn’t happen. I mean, I’m sure you must be very attractive to plenty of lesbians out there, but let’s face facts: they don’t look like Jennifer Beals, they look like Rosie O’Donnell. 2 MICHAEL (cont’d) That’s why the ‘L Word’ is just a TV show, and this is real life. And Pam, for what it’s worth, if you were a lesbian, you’d be one of the hotter ones. PAM Um, thanks. As Michael heads for his office, Pam turns to the camera. Her expression asks, “Did he just say that?” END TEASER INT. OFFICE - DAY It’s business as usual, when the entrance of an extremely attractive young woman (MARCI) interrupts the office’s normal placid calm. -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

District Attorney

GENERAL FUND DEPARTMENTS: Administration of Justice DISTRICT ATTORNEY MISSION The Fort Bend County District Attorney’s office represents the people of the State of Texas in all felony and misdemeanor criminal cases in the District Courts, County Courts at-Law, and Justice Courts. It is the primary duty of the District Attorney and his assistants, not to convict, but to see that justice is done. Additionally, the District Attorney represents the State in asset forfeiture cases, bond forfeiture cases, juvenile matters, and protective orders as well as aiding crime victims through its victim assistance coordinator. GOALS GOAL 1 Provide effective prosecution in all courts in order to effectively move the dockets while ensuring justice. Objective 1 Recruitment of prosecutors requires that we continue our dynamic internship program, whereby students are allowed to work and learn in a courtroom environment. Objective 2 Become more competitive with Harris County for prosecutors, and pay them at least 90 percent of what Harris County does. Objective 3 Upgrade positions to keep the best prosecutors. Currently, the office trains prosecutors to become excellent lawyers, only to have them leave (and take the County’s investment with them). A salary, which is more competitive with Harris County, should be achieved. GOAL 2 To improve prosecution in services, in order to ensure justice. Objective 1 Add assistants commensurate with the creation of new courts and increased caseload. Objective 2 As soon as practical, create an additional position for another full-time Assistant District Attorney to concentrate on filing of cases in the intake division. GOAL 3 Increase services to victims of family violence, in order to enhance education and protection of the public. -

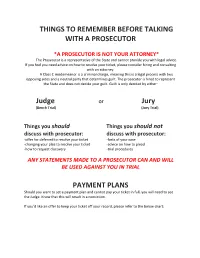

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

Julie Garcia District Attorney (Fmr.) Essex County, NY

Julie Garcia District Attorney (Fmr.) Essex County, NY Julie Garcia began her legal career in 1999 as an assistant district attorney within the Domestic Violence Unit of the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in New York, where she successfully prosecuted hundreds of domestic violence cases. In 2000, she moved to upstate New York to work in the Rensselaer County District Attorney’s Office and to be closer to family. After the death of her sister, she raised her two nieces and ran her own law firm, handling cases in Federal Court, Supreme Court, Family Court, County Court, and local courts for close to 20 years. In 2005, she made history by becoming the first woman elected District Attorney of Essex County. Her tenure as DA was focused on working to proactively reduce crime by collaborating with treatment agencies, law enforcement, probation, and other organizations to decrease underage drinking, driving while intoxicated, drug abuse, and domestic violence. Garcia left the District Attorney’s Office in 2009 and has since worked in private practice. She is a commissioner on the New York State Joint Commission on Public Ethics and is a sitting board member of the Legal Aid Society of Northeastern New York. She is a member of the Warren County Bar Association, Essex County Bar Association, Adirondack Women’s Bar Association, and New York State Defenders Association. She holds a BA in social work from Siena College and a JD from Albany Law School. The Law Enforcement Action Partnership is a nonprofit organization composed of police, prosecutors, judges, and other criminal justice professionals who use their expertise to advance drug policy and criminal justice solutions that improve public safety. -

Casino Skills for Working with Others Participant Manual: Edition 1.0

Casino Skills for Working with Others Participant Manual: Edition 1.0 Casino Skills for Working with Others: Essential Skills for the Gaming Industry Produced By: The Canadian Gaming Centre of Excellence (An operating division of The Manitoba Lotteries Corporation) 983 St. James Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3H 0X2 (204) 957-2504 ext. 8498 e-mail: [email protected] Contact: Judith Hayes, Director Dayna Hinkel, Business Development Officer © 2010 Canadian Gaming Centre of Excellence (CGCE). All rights reserved. All material in this manual is the property of the CGCE. This publication, or any part thereof, may be used free of charge and permission is granted to reproduce for personal or educational use only. Commercial copying or selling is prohibited. In all cases this copyright notice must remain intact. Special Thanks: The Canadian Gaming Centre of Excellence would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organizations and individuals in producing this manual: Aseneskak Casino Judy Goodridge, Chief Operating Officer Eleanor Gabriel, Human Resources Delores Lavallee, Manager, Human Resources Atlantic Lottery Corporation Alison Stultz, Director Organizational Development British Columbia Lottery Corporation: Mitch Romanchook, Manager Technical Services Talent Management – Human Resources Canadian Gaming Association Paul Burns, Vice President of Public Affairs Casino Rama Debra Pratt, Chief People Officer Century Casino & Hotel Nicole Jofre, Human Resources Great Canadian Gaming Corporation Sally Hart, Executive Director Human Resources -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE....................