The COLETTE SEWING HANDBOOK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

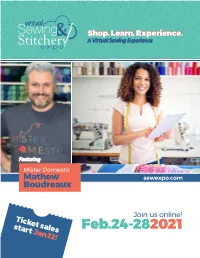

2021 Virtual Sewing & Stitchery Expo Schedule Checklist

Virtual Expo Schedule Use this checklist to plan your Virtual Expo experience. Don’t forget to buy your class tickets online beginning Jan. 12! All times listed are Pacific Standard Time (PST). Registration for Three & Four Needle classes that require a kit will end Feb. 2 to allow time for shipping. Wednesday 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4104 The Victorian Sewing Box 1:00 PM - 1:45 PM FS Lighting your Sewing Room 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4106 Beyond the Basics in Free Motion Quilting 1:00 PM - 2:00 PM Cutting Line Designs 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4107 Cadence Top Sew-A-Long 1:00 PM - 2:00 PM Fit for Art Patterns 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4110 A TempLee Quilted Medallion 1:00 PM - 2:00 PM The Rain Shed 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4111 From Thread to Lace 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4101 Flowermania English Paper Piecing 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4114 Scrappy Wonky Quilt Blocks 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4103 The Caprice Organizer 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4119 Temari—Japanese Thread Balls 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4105 Featherweight Spa Day 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4121 Easy Fit and Sew Yoga Pants 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4109 Enchantress Bracelet 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4122 The Ultimate Stabilizer Class 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4112 Vintage Windmill 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM 4123 Coverstitch Workshop 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4115 The Boro and Sashiko Pillow 9:00 AM - 9:30 AM FS Rulerwork Tips for Any Machine 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4117 Sew For You: Panties 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM WonderFil Specialty Threads 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4118 No Pins, No Basting, No Kidding! 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Paradiso Designs 1:00 PM - 5:00 PM 4120 Viking Knitting: Trichinopoly on a Dowel -

About the Designer ...Margaret Pierce

Bear in Mind An electronic newsletter from Bear Threads Ltd. Volume 3 – Issue 8 August 2011 From The Editor – About the designer . Margaret Pierce Jim and I just returned from a refreshing vacation to the Baltic’s Margaret has taught French Handsewing for 37 years. She and North Cape. Refreshing in many ways, not just the cool studied with Sarah Howard Stone in Montgomery, AL; with the temperatures – although I confess the temperatures ranged embroideresses on the island of Madeira; and at La Maison R. from the mid‐40s Fahrenheit at the North Cape to the mid‐60s Malbranche Embroidery School in Paris. She also received a BA in Home Economics Education at Queens University in in southern Norway. But the trip was refreshing also in seeing Charlotte, North Carolina. how the Scandinavian countries cling to their heritage with such zeal and commitment. Children still enjoy not only wearing the She taught for National and Regional SAGA and EGA Seminars native costumes of their local communities, but love sharing and Conventions; for Valentine Museum Assembly-Richmond, their local games, folklore and heritage. Girls continue to be VA; Callaway Gardens School of Needlework; in Ireland at the taught such arts as yarn spinning and fabric weaving as well as Au Grianan School for the Guild of Irish Lacemakers bread making and other ‘lost’ arts. We visited several working Convention; in Australia for the Australian Needlework School; museums which was very interesting. One mother and her 3 and local needlework guilds and shops throughout the US and small children were baking cinnamon rolls in the old fashioned Canada. -

Stitch Overview Utility Stitches

Stitch overview Utility stitches Stitch Stitch number Name Description For seaming and topstitching. Select from 37 different needle 1.1.1 Straight stitch positions. Note: This stitch makes a stronger tie-off than stitch 2.1.1. Stretch triple straight 1.1.2 Reinforced seam. Topstitching. stitch 1.1.3 Straight stitch reverse Sew continuous reverse with strong tie-off. Single stitch used for basting. Touch foot control to sew one stitch. 1.1.4 Basting stitch Move fabric manually to desired position and touch foot control again to sew another stitch. 1.1.5 Zigzag stitch 5HLQIRUFHVHDPVFOHDQÀQLVKVWUHWFKVHZLQJODFHLQVHUWLRQ Zigzag stitch, right or 1.1.6 5HLQIRUFHVHDPVFOHDQÀQLVKVWUHWFKVHZLQJ left needle position 1.1.7 Z-zigzag stitch Applique, couching, eyelets. Stretch triple zigzag 1.1.8 Elastic stitch for decorative hems or topstitching. stitch Three-step zigzag 1.1.9 Sewing elastic, darning, patching and decorative sewing. stitch 1.1.10 Elastic stitch Sewing elastic, darning, patching. 1.1.11 Triple stretch stitch Sewing elastic, darning, patching and decorative sewing. Decorative stitch for stretch fabrics and hems. Also used with elastic 1.1.12 Honeycomb stitch thread in the bobbin. Joining fabrics and quilt batting, decorative stitch for quilting, 1.1.13 Bridging stitch hemstitching. Foundation elastic Joining stitch for undergarments, terry cloth, leather, bulky fabrics 1.1.14 stitch where overlapping the seams. 1.1.15 Crosshem stitch Elastic decorative hem for stretch fabrics. 1.1.16 Blindhem stitch Sewing blindhems on woven fabrics. 1.1.17 Elastic blindhem stitch Sewing blindhems on stretch fabrics. 1.1.18 Stretch tricot stitch Sewing seams on stretch fabrics. -

Just Sew-It Twin Needles

BERNINA eBook Series JUST SEW IT! Exploring Twin Needles Written by Megann Freese EXPLORING TWIN NEEDLES In the wide array of techniques used in the sewing, quilting, and embroidery worlds, different needles are needed to provide the best results for every project. Twin needles, or double needles, are a type of needle that is often overlooked, but prove to be very useful in every category of sewing, not to mention that they are fun to use. Twin needles are two needles leading to two identical rows of parallel stitching accomplished using a single bobbin. Available in different types, sizes, and needle distances, there are few techniques that the twin needle cannot accomplish. This eBook discusses the anatomy of the twin needle, the different sizes and types, how to set up the sewing machine to operate with this type of needle, and different sewing techniques that are enhanced with the twin needle. ANATOMY How is the twin needle designed? The anatomy is simple: The two needles are connected to a single shank by a plastic bridge piece. The bridge piece acts as the shoulder for both needle shafts. Each needle has its own groove, eye, and point; however, both are the exact same size. The shank of a twin needle has a flat side, like that of a singular needle, which should be positioned to the back when inserted into the machine. Each needle has its own thread supply. Two spools of thread are needed for proper threading. NEEDLE ANATOMY LABELED Point Eye Shank Bridge Groove Two Needles PAGE 1 © 2020 BERNINA of America bernina.com EXPLORING TWIN NEEDLES HOW THE STITCHES ARE MADE In order to use a twin needle, or double needle, the sewing machine must be able to do a zigzag stitch. -

KVQG Library Book List 2017, by Author.Xlsx

KVQG Library Book List 2017, by author Author Title Filed Under Donated By 62 Group Contemporary British Textile Group C Carol Shankel Adams, B & Allen, A Nuts & Berries A Alma Allen Adams, B & Allen, A Summer Weekend A Alma Allen Adams, B. and Allen, A Women of Grace and Charm A donated 11/2017 Aiken, J & Jean Ray Laury The Total Tote Bag Books A Marge Ragle Alexander Karla New Cuts for New Quilts A Purchased 2012 Alexandrakis, Jessica Get Started Quilting A purchased 2017 American Quilt Renaissance American Quilt Renaisssance A Carol Shankel American Quilters Society 2004 Quilt Show CD FP&T American Quilters Society AQS Show & Contest (video - 2 copies) FP&T Andersen, Charlotte Warr Faces and Places - Images in Applique A Eva Hudson Andersen, Charlotte Warr One Line at a Time A Charlotte Andersen Ayers, Mimi See Campbell Pat Baatz, Barbara Iron-on Transfers for Quilt Labels B Babylon, Donna Decorator Quilts in a Hurry B Bacon, Lenice Ingram American Patchwork Quilts B Brackman/O'dowd Baker, Sharon K Fabulous Flowers B Purchased 2012 Bakker, Maaike Cups and Saucers B Martingale Barney, P & Schock, C Magic Base Block B Patchwork Place Becker, Joyce Nature's Paterns B Ellen Heck Bellino, Vicki English Paper Piecing Fresh New B Purchased 2/2014 Benberry, Cuesta & Crabb, C Love of Quilts B Mary Bouche Benberry, Cuesta & Crabb, C Patchwork of Pieces, A B Berg, Johnson, Van Holt Little Quilts B Better Homes and Gardens 501 Quilt Blocks B Better Homes and Gardens America's Patchwork and Quilting B Better Homes and Gardens Creative American -

2021 Class Catalog

Shop. Learn. Experience. A Virtual Sewing Experience Featuring Mister Domestic Mathew sewexpo.com Boudreaux Join us online! Ticket sales start Jan.12! Feb.24-282021 Mathew Boudreaux Sewist, Crafter, Teacher, Speaker, Designer, Advocate Mathew Boudreaux of Mister Domestic learned to sew as a kid, but never really got into it until he had his daughter Helena, who is now seven. He thought it would be a great way to connect with her if he could make her cool clothes. With a new motivation to up his attention-to-detail, the quality and coolness far exceeded even his own expectations. Once he started posting his projects on social media, the quilting world quickly took notice of his fearless use of color and print, incomprehensibly fast output, carefree enthusiasm and humor, and ability to seek out, acquire and share new skills. Making projects from fabric weaving to English Paper Piecing to apparel to the 3-Dimensional, you can find his fabric party on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. As a fabric designer, get ready to bring this party into overdrive as he translates his chic, edgy, and whimsical style into an experience for everyone to enjoy. Join Mathew at these Virtual Expo classes and special events! 4101 Flowermania English Paper Piecing WEDNESDAY, 1:00 - 5:00 PM (PST) Come learn English Paper Piecing with Mister Domestic! He’ll walk you through tips and tricks of this portable and super fun sewing technique as you stitch up your own flowers from his Flowermania Quilt Pattern. 4102 Tumbling Blocks Weave SUNDAY, 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PST) Fabric weaving is basically the coolest thing that you can do with fabric. -

163 Sophia Inst 11X17 New.Cdr

163 Revised: April 2018 seam allowance with the Seams Great using a long, wide zig zag stitch. Sophia On heavier fabrics including corduroy or velvet it is more difficult to fold the 163 General Sewing Information Seams Great in place. Place the edge of the Seams Great on the stitching line of Carefully READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS before beginning project. the seam and zig-zag in place. Then fold the Seams Great over the seam allowance and zig-zag again inclosing the seam allowance. Sophia has been redesigned! DO NOT CUT PATTERN SHEET. Trace onto tracing paper each pattern New Fit and Lengths, New Designs and More piece as needed. Be sure to mark your tracing with grain lines, fold lines and other Machine Finished Seam Allowance: Wide zig-zag stitch, three-step zig-zag information as given on pattern piece. These may be stored in small zipper seal stitch or serger stitch may also be used to finish seam allowances. If seam is to be Detailed Instructions Sophia pressed open, overcast the edges before stitching the seam. If seam will be bags inside your pattern. pressed to one side, overcast the raw edges after stitching the seam. Sizes 6 months to 10 years in one package! High Yoke Dresses Check Pattern Pieces for Correct Fit. Compare body measurements to measurements on back of pattern. Ready to wear clothing and pattern French Seam: companies use various standards and this will eliminate disappointment later. 1. Place fabric, wrong sides together and zig-zag stitch using a short narrow Sophia are very versatile round and square neck dresses. -

Threads of Love 8Th BI-Annual National Conference April 25-27

# Rec’d___________ Date Rec’d________ Check #__________ Amount__________ Threads of Love 8th BI-Annual National Conference April 25-27, 2018 Location: Greenwell Springs Baptist Church 19421 Greenwell Springs Rd Greenwell Springs, LA 70739 (225-261-2246) Non-Members Name: _______________________________________________________________________________________ **REQUIRED** Email: ________________________________________________ Name as you would like it to appear on name tag: _________________________________________ Address: ______________________________________________ City________________________________ STATE_________________ ZIP_______________ Phone: H (____) _____-___________Cell (_____) ______-_____________ Conference fee for Non-Members $ 100 I will be attending: Wednesday______ Thursday______ Friday______ (There will be a Kick Off Celebration on Wednesday after the Dinner Meal) I would like to make reservations for Wednesday (Dinner) to eat at the Church. (Meal cost $5, if over 55 $4) *** How many – Myself_____ or Myself and Spouse_______ or Myself and Guest(s)_____ Spouse name if attending conference: _______________________________________ Meals for spouse------------------------ $35.00 **Please make Conference check out to Threads of Love and MUST be attached with your application. If you do not cancel by April 4, 2018 the Conference Cancellation fee will be forfeited. * Conference includes: Classes, Wednesday Lunch, Thursday & Friday Lunch & Dinner, and Snacks. ***Conference Cancelation Fee -----MUST CANCEL by April 4, 2018 or forfeit your $100 for non-members*** If you are flying into Baton Rouge, We can make-arrangements for transportation. Need transportation □ Arriving on 4 /__ / 2018 Airline______________________ Flight # _________ Arrival Time_____________ I will be returning home on Day________, Date___________, and Time____________ There will be 10 Baby Lock Sewing machines available for your use on a first-come-first-serve basis. If you would like to Reserve one, check here. -

Heirloom-Sewing-2017-Brochure.Pdf

EMELINE’S DIAGONAL LACE DRESS WITH WENDY SCHOEN Please join me in my studio for 5 full days of heirloom sewing! This class is structured on the premise of a christening gown I designed some years ago and taught at the Martha Pullen School in Alabama. One student, Cindy Farmer, asked if she could make a child’s dress instead of a christening gown and knowing her sewing skills, I agreed as long as she could provide the alterations on her own. This beautiful creation is the result and wow! I was blown away, much like the rest of the heirloom sewing family. Her pins on pinterest went viral on the internet and I have been itching to do this class ever since. Luckily, Cindy agreed. In order to participate in this workshop, you must have a basic knowledge of heirloom sewing and have completed at least one garment using the traditional roll and whip method of joining laces. I would place this project as an Advanced Beginner to Intermediate Level sewing class. I am offering a kit for this workshop but if you wish, you may bring your own materials instead. Many of you have been collecting lace for years and I would love to see your vision fulfilled while making this magnificent creation. I can assist you in choosing lace configurations and fabric choice. You have the chance to make it a “One of a Kind” creation. My 30-plus years of sewing and teaching experience and drafting and fitting expertise will help you create the perfect dress up to a size 6. -

Important Safety Instructions

IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using an electrical appliance, basic safety 3. Never operate this sewing computer if precautions should always be followed, including • it has a damaged cord or plug the following: • it is not working properly • it has been dropped or damaged Read all instructions before using this sewing • it has fallen into water computer. Return the sewing computer to the nearest authorized BERNINA dealer or service center When the sewing computer is not in use, it for examination, repair, electrical or mechanical should be disconnected from the electricity adjustment. supply by removing the plug from the outlet. 4. Never operate the sewing computer with any air openings blocked. Keep ventilation openings of the sewing computer and foot controller free from accumulation of lint, dust and loose DANGER cloth. 5. Keep fingers away from all moving parts. To reduce risk of electrical shock: Special care is required around the sewing needle. 1. An appliance should never be left unattended when plugged in. 6. Always use the BERNINA original stitch plate. The wrong plate can cause the needle 2. Always unplug this sewing computer from to break. the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning. 7. Do not use bent needles. 8. Do not pull or push fabric while stitching. It may deflect the needle, causing it to break. 9. Turn power switch to «0» (off) when making WARNING any adjustments in the needle area, such as threading or changing the needle, threading To reduce the risk of burns, fire, electric shock the bobbin or changing the presser foot etc. -

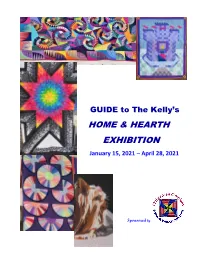

GUIDE to the Kelly's

GUIDE to The Kelly’s HOME & HEARTH EXHIBITION January 15, 2021 – April 28, 2021 Sponsored by Elements of Art in Quilting Fabric art is often overlooked or undervalued in the art world. People will spend $100’s on a painting, but expect someone to sew for free or well less than minimum wage. Maybe that is because so many of our quilts have been heirlooms, received free with inheritance or as a gift. There is expectation that a quilt is just made of old clothes, which truly was a necessity in the past. However, today quilting and other handwork have really been raised to an art form, one more method of expression. Proof? COLOR—like other art, color is of major consideration in quilting CHIAROSCURO or CONTRAST—is very important to showcase the design MOTIF or more general REPETITION—certainly, many quilts are made with blocks that are repetitive by nature; some have repeated motifs IMAGE—whether appliquéed in place or created by the blocks, many quilts and wall hangings have gorgeous images. A few mimic photographs or even have photos worked into the design. They also often have BALANCE and even PERSPECTIVE. TEXTURE—the very nature of quilting creates texture, but more and more fabric artists are working 3-dimensional elements into the designs as well ORIGINALITY—while some quilters follow patterns almost like paint-by-numbers, others design their own patterns or bring original elements into traditional patterns That originality plus the other elements takes sewing or quilting from a craft to an art form. I am delighted to be allowed to sponsor this marvelous exhibit that displays such wonderful needlework. -

Stitches Stitch № Presser Name Description Foot A1 a Straight Stitch, Center for All Types of Sewing

Stitch Overview Utility Stitches Stitch № Presser Name Description foot A1 A Straight stitch, center For all types of sewing. needle position A2 A Straight stitch with For all types of sewing. Begins and ends with forward and reinforced tie-off reverse stitches. A3 A Stretch stitch, left needle For seams in tricot and stretch fabrics. position A4 A Zigzag, center needle For sewing on lace, trims and appliqués. position A5 A Reinforced straight stitch, Triple and elastic, for reinforced seams. For top stitch, increase center needle position the stitch length. A6 B Reinforced zigzag stitch For joining fabric edge to edge or overlapping in leather. For decorative sewing. A7 J Seam/overcast stitch Seam and overcast in one step along the edge or trim later. For light stretch and non-stretch fabrics. A8 B Stretch seam/overcast Seam and overcast in one step along the edge or trim later. For stitch medium and heavy stretch fabrics. A9 B Double overlock stitch Seam and overcast in one step along the edge or trim later. For heavy stretch and heavy woven fabrics. A10 B Overlock stitch Seam and overcast in one step along the edge or trim later. For medium stretch fabrics. A11 B Flatlock stitch Decorative hems and overlapped seams, belts and bands. For medium/heavy stretch fabrics. A12 D Stretch blind hem stitch Blind hems in medium and heavy stretch fabrics. A13 D Woven blind hem stitch Blind hems in medium and heavy woven fabrics. A14 A Shell edge stitch For edging, sewing over the edge on light woven fabrics.