Emergency Cesarean Delivery for Umbilical Cord Prolapse: the Head

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Induction of Labor

36 O B .GYN. NEWS • January 1, 2007 M ASTER C LASS Induction of Labor he timing of parturi- nancies that require induction because of medical com- of labor induction, the timing of labor induction, and the tion remains a conun- plications in the mother. advisability of the various conditions under which in- Tdrum in obstetric Increasingly, however, patients are apt to have labor in- duction can and does occur. medicine in that the majority duced for their own convenience, for personal reasons, This month’s guest professor is Dr. William F. Rayburn, of pregnancies will go to for the convenience of the physician, and sometimes for professor and chairman of the department of ob.gyn. at term and enter labor sponta- all of these reasons. the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Ray- neously, whereas another This increasingly utilized social option ushers in a burn is a maternal and fetal medicine specialist with a na- portion will go post term and whole new perspective on the issue of induction, and the tional reputation in this area. E. ALBERT REECE, often require induction, and question is raised about whether or not the elective in- M.D., PH.D., M.B.A. still others will enter labor duction of labor brings with it added risk and more com- DR. REECE, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is prematurely. plications. Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, The concept of labor induction, therefore, has become It is for this reason that we decided to develop a Mas- and the John Z. -

ABCDE Acronym Blood Transfusion 231 Major Trauma 234 Maternal

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-26827-1 - Obstetric and Intrapartum Emergencies: A Practical Guide to Management Edwin Chandraharan and Sir Sabaratnam Arulkumaran Index More information Index ABCDE acronym albumin, blood plasma levels 7 arterial blood gas (ABG) 188 blood transfusion 231 allergic anaphylaxis 229 arterio-venous occlusions 166–167 major trauma 234 maternal collapse 12, 130–131 amiadarone, overdose 178 aspiration 10, 246 newborn infant 241 amniocentesis 234 aspirin 26, 180–181 resuscitation 127–131 amniotic fluid embolism 48–51 assisted reproduction 93 abdomen caesarean section 257 asthma 4, 150, 151, 152, 185 examination after trauma 234 massive haemorrhage 33 pain in pregnancy 154–160, 161 maternal collapse 10, 13, 128 atracurium, drug reactions 231 accreta, placenta 250, 252, 255 anaemia, physiological 1, 7 atrial fibrillation 205 ACE inhibitors, overdose 178 anaerobic metabolism 242 automated external defibrillator (AED) 12 acid–base analysis 104 anaesthesia. See general anaesthesia awareness under anaesthesia 215, 217 acidosis 94, 180–181, 186, 242 anal incontinence 138–139 ACTH levels 210 analgesia 11, 100, 218 barbiturates, overdose 178 activated charcoal 177, 180–181 anaphylaxis 11, 227–228, 229–231 behaviour/beliefs, psychiatric activated partial thromboplastin time antacid prophylaxis 217 emergencies 172 (APTT) 19, 21 antenatal screening, DVT 16 benign intracranial hypertension 166 activated protein C 46 antepartum haemorrhage 33, 93–94. benzodiazepines, overdose 178 Addison’s disease 208–209 See also massive -

Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline

Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline Document Control Title Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline Author Author’s job title Specialty Trainee in Obstetrics and Gynaecology Directorate Department Women’s and Children’s Obstetrics and Gynaecology Date Version Status Comment / Changes / Approval Issued 1.0 Mar Final Approved by the Maternity Services Guideline Group in 2011 April 2011. 1.1 Aug Revision Minor amendments by Corporate Governance to 2012 document control report, headers and footers, new table of contents, formatting for document map navigation. 2.0 Feb Final Approved by the Maternity Services Guideline Group in 2016 February 2016. 2.1 Apr Revision Harmonised with Royal Devon & Exeter guideline 2019 3.0 May Final Approved by Maternity Specialist Governance Forum 2019 meeting on 01.05.2019 Main Contact ST1 O&G Tel: Direct Dial– 01271 311806 North Devon District Hospital Raleigh Park Barnstaple Devon EX31 4JB Lead Director Medical Director Superseded Documents Nil Issue Date Review Date Review Cycle May 2019 May 2022 Three years Consulted with the following stakeholders: (list all) Senior obstetricians Senior midwives Senior management team Filename Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline v3. 01May 19.doc Policy categories for Trust’s internal Tags for Trust’s internal website (Bob) website (Bob) Cord, accidents, prolapse Maternity Services Maternity Page 1 of 11 Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline CONTENTS Document Control .................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction -

Management of Prolonged Decelerations ▲

OBG_1106_Dildy.finalREV 10/24/06 10:05 AM Page 30 OBGMANAGEMENT Gary A. Dildy III, MD OBSTETRIC EMERGENCIES Clinical Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Management of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans prolonged decelerations Director of Site Analysis HCA Perinatal Quality Assurance Some are benign, some are pathologic but reversible, Nashville, Tenn and others are the most feared complications in obstetrics Staff Perinatologist Maternal-Fetal Medicine St. Mark’s Hospital prolonged deceleration may signal ed prolonged decelerations is based on bed- Salt Lake City, Utah danger—or reflect a perfectly nor- side clinical judgment, which inevitably will A mal fetal response to maternal sometimes be imperfect given the unpre- pelvic examination.® BecauseDowden of the Healthwide dictability Media of these decelerations.” range of possibilities, this fetal heart rate pattern justifies close attention. For exam- “Fetal bradycardia” and “prolonged ple,Copyright repetitive Forprolonged personal decelerations use may onlydeceleration” are distinct entities indicate cord compression from oligohy- In general parlance, we often use the terms dramnios. Even more troubling, a pro- “fetal bradycardia” and “prolonged decel- longed deceleration may occur for the first eration” loosely. In practice, we must dif- IN THIS ARTICLE time during the evolution of a profound ferentiate these entities because underlying catastrophe, such as amniotic fluid pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical 3 FHR patterns: embolism or uterine rupture during vagi- management may differ substantially. What would nal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC). The problem: Since the introduction In some circumstances, a prolonged decel- of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) in you do? eration may be the terminus of a progres- the 1960s, numerous descriptions of FHR ❙ Complete heart sion of nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns have been published, each slight- block (FHR) changes, and becomes the immedi- ly different from the others. -

Cord Prolapse

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CORD PROLAPSE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CORD PROLAPSE Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland and the Clinical Strategy and Programmes Division, Health Service Executive Version: 1.0 Publication date: March 2015 Guideline No: 35 Revision date: March 2017 1 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CORD PROLAPSE Table of Contents 1. Revision History ................................................................................ 3 2. Key Recommendations ....................................................................... 3 3. Purpose and Scope ............................................................................ 3 4. Background and Introduction .............................................................. 4 5. Methodology ..................................................................................... 4 6. Clinical Guidelines on Cord Prolapse…… ................................................ 5 7. Hospital Equipment and Facilities ....................................................... 11 8. References ...................................................................................... 11 9. Implementation Strategy .................................................................. 14 10. Qualifying Statement ....................................................................... 14 11. Appendices ..................................................................................... 15 2 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CORD PROLAPSE 1. Revision History Version No. -

OBGYN-Study-Guide-1.Pdf

OBSTETRICS PREGNANCY Physiology of Pregnancy: • CO input increases 30-50% (max 20-24 weeks) (mostly due to increase in stroke volume) • SVR anD arterial bp Decreases (likely due to increase in progesterone) o decrease in systolic blood pressure of 5 to 10 mm Hg and in diastolic blood pressure of 10 to 15 mm Hg that nadirs at week 24. • Increase tiDal volume 30-40% and total lung capacity decrease by 5% due to diaphragm • IncreaseD reD blooD cell mass • GI: nausea – due to elevations in estrogen, progesterone, hCG (resolve by 14-16 weeks) • Stomach – prolonged gastric emptying times and decreased GE sphincter tone à reflux • Kidneys increase in size anD ureters dilate during pregnancy à increaseD pyelonephritis • GFR increases by 50% in early pregnancy anD is maintaineD, RAAS increases = increase alDosterone, but no increaseD soDium bc GFR is also increaseD • RBC volume increases by 20-30%, plasma volume increases by 50% à decreased crit (dilutional anemia) • Labor can cause WBC to rise over 20 million • Pregnancy = hypercoagulable state (increase in fibrinogen anD factors VII-X); clotting and bleeding times do not change • Pregnancy = hyperestrogenic state • hCG double 48 hours during early pregnancy and reach peak at 10-12 weeks, decline to reach stead stage after week 15 • placenta produces hCG which maintains corpus luteum in early pregnancy • corpus luteum produces progesterone which maintains enDometrium • increaseD prolactin during pregnancy • elevation in T3 and T4, slight Decrease in TSH early on, but overall euthyroiD state • linea nigra, perineum, anD face skin (melasma) changes • increase carpal tunnel (median nerve compression) • increased caloric need 300cal/day during pregnancy and 500 during breastfeeding • shoulD gain 20-30 lb • increaseD caloric requirements: protein, iron, folate, calcium, other vitamins anD minerals Testing: In a patient with irregular menstrual cycles or unknown date of last menstruation, the last Date of intercourse shoulD be useD as the marker for repeating a urine pregnancy test. -

Term Pregnancy with Umbilical Cord Prolapse

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 51 (2012) 375e380 www.tjog-online.com Original Article Term pregnancy with umbilical cord prolapse Jian-Pei Huang a,b,*, Chie-Pein Chen a,c, Chih-Ping Chen a,d, Kuo-Gon Wang a,c, Kung-Liahng Wang a,b,d a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan b Mackay Medicine, Nursing and Management College, Taipei, Taiwan c Division of High Risk Pregnancy, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan d Department of Medical Research, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan Accepted 10 March 2011 Abstract Objective: To investigate the incidence, management, and perinatal and long-term outcomes of term pregnancies with umbilical cord prolapse (UCP) at Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, from 1998 to 2007. Materials and Methods: For this retrospective study, we reviewed the charts, searched a computerized birth database, and contacted the families by telephone to acquire additional follow-up information. Results: A total of 40 cases of UCP were identified among 40,827 term deliveries, an incidence of 0.1%. Twenty-six cases (65%) were delivered by emergency cesarean section (CS). Of the neonates, 18 had an Apgar score of <7 at 1 minute, 10 of these scores being sustained at 5 minutes after birth, and three infants finally died. Eleven UCPs occurred at the vaginal delivery of a second twin, and nine with malpresentation. All of the infants who had good perinatal outcomes also had good long-term outcomes. -

Umbilical Cord Prolapse

Cord prolapse 2013–15 UMBILICAL CORD PROLAPSE All staff involved in maternity care should receive at least annual training in the management of obstetric emergencies including umbilical cord prolapse DEFINITION Descent of umbilical cord through cervix alongside (occult) or past presenting part (overt) in the presence of ruptured membranes Background Incidence of cord prolapse is between 0.1–0.6% 50% of cases are preceded by obstetric manipulation Cord prolapse carries a perinatal mortality rate of 91/1000 in hospital settings, mortality is largely secondary to prematurity and congenital malformations Cord prolapse is also associated with birth asphyxia asphyxia, predominantly caused by cord compression and umbilical arterial vasospasm, can result in long-term morbidity because of hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (see Staffordshire, Shropshire & Black country Newborn network Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy guideline) and cerebral palsy RECOGNITION AND ASSESSMENT Symptoms and signs Cord presentation and prolapse may occur with no outward physical signs and with a normal fetal heart rate pattern Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern (e.g. bradycardia, variable decelerations, prolonged deceleration of >1 min – particularly if soon after membrane rupture) Cord seen or felt at vaginal examination Investigations Auscultate fetal heart soon after rupture of membranes Routine vaginal examination is not indicated if liquor clear with spontaneous rupture of membranes in the presence of normal fetal heart rate and absence of risk factors Cord -

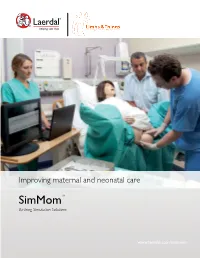

Simmomtm Birthing Simulation Solutions

Improving maternal and neonatal care SimMomTM Birthing Simulation Solutions www.laerdal.com/simmom Innovative simulation Improving patient safety Preventing adverse outcomes during birth Simulation has gathered increasing acceptance over the Simulation training is unique in its ability to facilitate effective years as an integral part of healthcare training and as a team training. By bringing together multi-disciplinary fundamental approach to help improve patient safety. healthcare professionals in a simulation to rehearse both common birthing scenarios and emergency critical incidents; In the field of obstetrics, research into suboptimal patient early recognition of birth complications, correct diagnosis outcomes have identified the following key contributory and rapid, coordinated action from the delivery team can factors: confusion in roles and responsibilities; lack of cross be perfected for improved outcomes. monitoring; failure to prioritize and perform clinical tasks in a structured, coordinated manner; poor communication and lack of organizational support. Reference : The Joint Commission, 2004, Draycott et al. 2009 2 Simulation by Laerdal and Limbs & Things SimMomTM A complete solution A progressive partnership SimMomTM is an advanced full-body birthing simulator with By integrating the strengths of the PROMPT birthing accurate anatomy and functionality. SimMom has been simulator from Limbs & Things with the ALS Simulator developed to provide you with a comprehensive simulation from Laerdal, SimMom provides anatomical accuracy and solution to support multi-disciplined staff in obstetric and authentic simulation experiences that together, facilitate midwifery care, enabling refinement of individual skills and valuable learning experiences for a wide range of midwifery team performance. and obstetric skills. With a range of Technical and Educational Services as well as pre-programmed scenarios to ease educator preparation time, SimMom is the optimal simulation experience. -

Cord Prolapse MATY021

Document ID: MATY021 Version: 1.0 Facilitated by: Eleanor Martin, Educator Issue Date: August 2011 Approved by: Maternity Quality Committee Review date: March 2017 Cord Prolapse Policy Purpose of the policy The purpose of this policy is to • provide safe and effective care for women and their babies when a cord prolapse or presentation is diagnosed in the intrapartum period • establish a local approach to care, that is evidence based and consistent • inform good decision making Scope • All obstetric staff employed by the Hutt Valley DHB • All midwifery staff employed by the Hutt Valley DHB • All Hutt Valley DHB maternity access agreement holders. • Anaesthetic staff • Neonatal staff Abbreviations used in this document ARM Artificial rupture of membranes C/S Caesarean Section ROM Rupture of membranes SROM Spontaneous rupture of membranes Definitions Cord Presentation It is the presence of the umbilical cord between the foetal presenting part and cervix with or without rupture of membranes RCOG, 2008.p1 Cord Prolapse It is the descent of the umbilical cord through the cervix alongside (occult) or past the presenting part (overt) with ruptured membranes RCOG, 2008.p1 Complications Maternal Operative delivery and anaesthesia Haemorrhage Sepsis Post-traumatic stress Foetal Hypoxia Death Risk Assessment Women with known antenatal risk factors should have a well-documented care plan. Practitioners should refer to the Referral Guidelines Risk factors for Cord Prolapse General High presenting part Polyhydramnios Prematurity Cord presentation on ultrasound Malpresentation (e.g. breech, transverse lie) Birth weight < 2500g Multiparity Procedure related Artificial Rupture of Membranes External Cephalic Version Internal Podalic Version Application of foetal scalp electrode Rotational instrumental delivery Prevention of Cord Prolapse Cord prolapse often cannot be avoided. -

Chapter 14 CORD PROLAPSE

Perinatal Manual of Southwestern Ontario Southwestern Ontario Maternal, Newborn, Child & Youth Network (MNCYN) Perinatal Outreach Program Chapter 14 CORD PROLAPSE Cord prolapse occurs in 1/200 to 1/400 pregnancies. Perinatal mortality ranges from 0.02% to 12.6%. The outlook for the fetus is influenced by the degree and duration of cord compression and the time interval between the diagnosis and birth. Definition: Umbilical cord prolapse is defined as the descent of the umbilical cord through the cervix alongside (occult) or past the presenting part (overt) in the presence of ruptured membranes. Cord presentation is the presence of the umbilical cord between the fetal presenting part and the cervix, with or without membrane rupture Risk Factors 1. Malpresentation: more common when preterm, multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, pelvic tumors 2. Unstable lie 3. Hydramnios 4. Grand multiparous women i.e., parity of >5 5. Rupture of membranes when the presenting part is high 6. Preterm rupture of membranes 7. CPD 8. Placenta previa, low lying placenta 9. Male gender 10. Fetal congenital anomalies 11. Birth weight less than 2500 g 12. Pelvic tumours Presentation 1. Sudden fetal bradycardia 2. Patient complaint that something is coming from the vagina 3. Visual – umbilical cord seen at introitus (majority are hidden in vagina, therefore, diagnosis is not always easy) 4. Palpation of the cord on vaginal examination Revised October 2018 14-1 Disclaimer The Southwestern Ontario Maternal, Newborn, Child & Youth Network (MNCYN) has used practical experience and relevant legislation to develop this manual chapter. We recommend that this chapter only be used as a reference document at other facilities. -

Perinatal Factors Affecting Human Development

PERINATAL FACTORS AFFECTING HUMAN DEVELOPMENT PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 1969 PERINATAL FACTORS AFFECTING HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Proceedings of the Special Session held during the Eighth Meeting of the PAHO Advisory Committee on Medical Research 10 June 1969 Scientific Publication No. 185 October 1969 PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 525 Twenty-third Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20037, U.S.A. NOTE At each meeting of the Pan American Health Organization Advisory Committee on Medical Research, a special session is held on a topic chosen by the Committee as being of particular interest. At the Eighth Meeting, which convened in June 1969 in Washington, D.C., the session surveyed some of the factors which may act on the fetus during pregnancy and labor interfering with its normal development or causing irreversible damage. Their influence on perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as their, long-term consequences on the surviving child received special attention. The basis for early diagnosis, prevention and trcatment was carefully reviewed. This volume records the papers presented and the ensuing discussions. PAHO ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON MEDICAL RESEARCH Dr. Hernán Alessandri Dr. Robert Q. Marston Ex-Decano, Facultad de Medicina Director, National Institutes of Health Universidad de Chile Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A. Santiago, Chile Dr. Walsh McDermott Dr. Otto G. Bier Chairman, Department of Public Health Director, PAHO/WHO Immunology Cornell University Medical College Research and Training Center New York, New York, U.S.A. Instituto Butantan Sao Paulo, Brazil Dr.