Humanitarian Experiences with Sexual Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

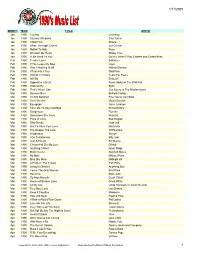

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

02 March 1997 CHART #1048 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Lovefool Champagne Romeo & Juliet Soundtrack Recurring Dream: The Very Best 1 The Cardigans 21 Salt N Pepa 1 Various 21 Crowded House Last week - / 1 weeks POLYDOR/POLYGRAM Last week 17 / 4 weeks MCA/UNIVERSAL Last week 1 / 5 weeks Platinum / EMI Last week 18 / 31 weeks Platinum / EMI I Believe I Can Fly It's Friday Night Secret Samadhi 18 'Til I Die 2 R. Kelly 22 D.B.A. Flip 2 Live 22 Bryan Adams Last week 2 / 5 weeks Gold / WARNER Last week 32 / 3 weeks SONY Last week - / 1 weeks Gold / UNIVERSAL Last week 28 / 23 weeks Platinum / A&M/POLYGRAM Firestarter Too Much Heaven Forgiven Not Forgotten Tour Pack How Bizarre 3 The Prodigy 23 Jordan Hill 3 The Corrs 23 OMC Last week 8 / 5 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 23 / 5 weeks WARNER Last week 2 / 16 weeks Platinum / WARNER Last week 21 / 9 weeks Gold / HUH!/POLYGRAM Discotheque Young Hearts Run Free Tragic Kingdom Spacejam OST 4 U2 24 Kim Mazelle 4 No Doubt 24 Various Last week 1 / 2 weeks ISLAND/POLYGRAM Last week 31 / 5 weeks EMI Last week 3 / 28 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 24 / 9 weeks WARNER These Are The Days Of Our Livez Say You'll Be There Spice Aenima 5 Bone Thugs N Harmony 25 Spice Girls 5 Spice Girls 25 Tool Last week - / 1 weeks WARNER Last week 14 / 14 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN Last week 7 / 10 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN Last week 29 / 16 weeks Gold / BMG Don't Cry For Me Argentina Fallin' The Last Great Romantic Antichrist Superstar 6 Madonna 26 Montell Jordan 6 David Helfgott 26 Marilyn Manson Last week - / 1 weeks WARNER Last week -

The Widow of Valencia

FÉLIX LOPE DE VEGA Y CARPIO THE WIDOW OF VALENCIA Translated by the UCLA Working Group on the Comedia in Translation and Performance: Marta Albalá Pelegrín Paul Cella Adrián Collado Barbara Fuchs Rafael Jaime Robin Kello Jennifer L. Monti Laura Muñoz Javier Patiño Loira Payton Phillips Quintanilla Veronica Wilson Table of Contents The Comedia in Context A Note on the Playwright Introduction—Robin Kello and Laura Muñoz Pronounciation Key Dedication The Widow of Valencia Characters Act I Act II Act III The Comedia in Context The “Golden Age” of Spain offers one of the most vibrant theatrical repertoires ever produced. At the same time that England saw the flourishing of Shakespeare on the Elizabethan stage, Spain produced prodigious talents such as Lope de Vega, Tirso de Molina, and Calderón de la Barca. Although those names may not resonate with the force of the Bard in the Anglophone world, the hundreds of entertaining, complex plays they wrote, and the stage tradition they helped develop, deserve to be better known. The Diversifying the Classics project at UCLA brings these plays to the public by offering English versions of Hispanic classical theater. Our translations are designed to make this rich tradition accessible to students, teachers, and theater professionals. This brief introduction to the comedia in its context suggests what we might discover and create when we begin to look beyond Shakespeare. Comedia at a Glance The Spanish comedia developed in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. As Madrid grew into a sophisticated imperial capital, the theater provided a space to perform the customs, concerns, desires, and anxieties of its citizens. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Not ß8b Ai Play

Billboard. FEBRUARY 15, 1997 Billboard FEBRUARY 15, 1997 R &B SINGLES A -Z TITLE (Publisher - Licensing Chg.) Sheet Music Dist 52 AIN'T NOBODY (FROM BEAVIS AND BUTT -HEAD DO AMERICA) (Full Keel, ASCAP) WBM Not ß8B Ai play.. 40 ASCENSION (DONT EVER WONDER) (Sony/AN Tunes ILC, Not ß &B Sin pIes Sales.. ASCAP/Muszewell, ASCAP/)tall Shur. BMVTMI Apnl, ASCAP) HL Compiled from a national sample of airplay supplied by Broa dcast Data Systems' Radio Track service. 95 R&B stations Compiled from a national sub -sample or PUB tpoint of sal e) equipped trey H58 retail stores slnch report number 54 ATLIENS/WHEELZ OF STEEL (Chrysalis. ASCAP /Gnat are electronically monitored 24 hours a day. 7 days a week. Songs ranked by gross impressions, computed by cross - of units sold to SoundScan, Inc. This data Is used in the F lot R&D Singles chart. Booty, ASCAP) WBM referencing exact times of airplay with Arbitron listener data. This data is used in the Hot R&B Singles chart. SoundScanX 95 BEEN FOUND (Nick -O -Val. ASCAP /Guycol. ASCAP) lull," 96 BEFORE I LAY (YOU DRIVE ME CRAZY) (Joel Halley. ASCAP/EMI Y April, ASCAP/WB. ASCAP/D Xhaordenary. ASCAP) WBM 2 Y Px. oz = Ó O 93 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY (FROM HIGH SCHOOL HIGH) III O 3 3 3 (B. Feldman 8 Co./Trident. ASCAP/Glenwood, ASCAP) HL 3 TITLE 'i TITLE W TITLE 3 CANT NOBODY HOLD ME DOWN Dustin Combs. ASCAP/EMI TITLE 3 ARTIST ILABEUPROMOTION LABEL) 4 S ARTIST ILABEUPROMOTION LABEL) 3 ARTIST (LABEUPROMOTION LABEL) E S 3 ARTIST (LABEL/PROMOTION LABEL) April. -

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

The Influence of Patriarchy on Otoko and Keiko's

THE INFLUENCE OF PATRIARCHY ON OTOKO AND KEIKO’S LESBIANISM IN KAWABATA’S BEAUTY AND SADNESS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ANGELA ASTRID S. C. A. 044214024 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis THE INFLUENCE OF PATRIARCHY IN 20TH CENTURY JAPAN ON OTOKO AND KEIKO’S LESBIANISM IN KAWABATA’S BEAUTY AND SADNESS By ANGELA ASTRID S. C. A. Student Number: 044214024 Approved by Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani., S.S., M.Hum Date: Advisor Elisa Dwi Wardani, S.S., M.Hum Date: Co-Advisor ii A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis THE INFLUENCE OF PATRIARCHY IN 20TH CENTURY JAPAN ON OTOKO AND KEIKO’S LESBIANISM IN KAWABATA’S BEAUTY AND SADNESS By ANGELA ASTRID S. C. A. Student Number: 044214024 Defended before the Board of Examiners on September 27, 2008 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairman : Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. ______________________ Secretary : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M. Hum. ______________________ Member : Adventina Putranti S.S., M. Hum ______________________ Member : Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani., S.S., M.Hum ______________________ Member : Elisa Dwi Wardani, S.S., M.Hum ______________________ Yogyakarta, September 27, 2008 Faculty of Letters Sanata Dharma University Dean Dr. I. Praptomo Baryadi, M.Hum. iii Around here, however, we don’t look backwards for very long..... We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious.... And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths iv This thesis I dedicate to my lovely parents my brother and sister and all of my friends love you all v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I give my deepest thanks to My Lord Jesus Christ for His guidance so that I could finish my thesis. -

Tupac Shakur 29 Dr

EXPONENTES DEL VERSO computación PDF generado usando el kit de herramientas de fuente abierta mwlib. Ver http://code.pediapress.com/ para mayor información. PDF generated at: Sat, 08 Mar 2014 05:48:13 UTC Contenidos Artículos Capitulo l: El mundo de el HIP HOP 1 Hip hop 1 Capitulo ll: Exponentes del HIP HOP 22 The Notorious B.I.G. 22 Tupac Shakur 29 Dr. Dre 45 Snoop Dogg 53 Ice Cube 64 Eminem 72 Nate Dogg 86 Cartel de Santa 90 Referencias Fuentes y contribuyentes del artículo 93 Fuentes de imagen, Licencias y contribuyentes 95 Licencias de artículos Licencia 96 1 Capitulo l: El mundo de el HIP HOP Hip hop Hip Hop Orígenes musicales Funk, Disco, Dub, R&B, Soul, Toasting, Doo Wop, scat, Blues, Jazz Orígenes culturales Años 1970 en el Bronx, Nueva York Instrumentos comunes Tocadiscos, Sintetizador, DAW, Caja de ritmos, Sampler, Beatboxing, Guitarra, bajo, Piano, Batería, Violin, Popularidad 1970 : Costa Este -1973 : Costa, Este y Oeste - 1980 : Norte America - 1987 : Países Occidentales - 1992 : Actualidad - Mundial Derivados Electro, Breakbeat, Jungle/Drum and Bass, Trip Hop, Grime Subgéneros Rap Alternativo, Gospel Hip Hop, Conscious Hip Hop, Freestyle Rap, Gangsta Rap, Hardcore Hip Hop, Horrorcore, nerdcore hip hop, Chicano rap, jerkin', Hip Hop Latinoamericano, Hip Hop Europeo, Hip Hop Asiatico, Hip Hop Africano Fusiones Country rap, Hip Hop Soul, Hip House, Crunk, Jazz Rap, MerenRap, Neo Soul, Nu metal, Ragga Hip Hop, Rap Rock, Rap metal, Hip Life, Low Bap, Glitch Hop, New Jack Swing, Electro Hop Escenas regionales East Coast, West Coast, -

Tamara Moir - Poems

Poetry Series Tamara Moir - poems - Publication Date: 2006 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Tamara Moir(22/03/1991) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 *~*tears*~*and*~*blood*~* Alone Red Tears Falling From Her Wrists Heart On The Floor Flooding The Room With Her Tears And Blood Tamara Moir www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 A Best Friend I can be quite smart And I am always clever That’s why you’re in my heart Always and Forever Threw the good! Wonderful times! And then the trouble And Frustrating Climbs Over the Hill Is half way there Were not there yet: But we don't care! As long as we are together Threw the laughs and the tears We will still have fun Over these countless years When we reach to top Of that hard steep hill! We would still be together When were old and ill And when we look back To reflect on years We will laugh and have fun! But we might shed some tears! Because we'll be old And it’s the end of our life Im not so scared Because we've reached high heights I want you to know That i love you so Were Best Friends for life And that’s what I’ve shown This is the best That I could describe You’re my best friend And i can’t let it hide! I love you www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 Tamara Moir www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 4 A Broken Mirror A broken mirror A distorted face A shattered heart A clear distaste A fallen tear A reddened eye A downturned mouth A year gone by A loaded gun A finished fear A bloodied wall A broken mirror.. -

Jermaine Dupri Instructions Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jermaine Dupri Instructions mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Instructions Country: US Released: 2001 MP3 version RAR size: 1945 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1538 mb WMA version RAR size: 1585 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 675 Other Formats: ASF FLAC MPC MP3 MP4 APE AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Intro Welcome To Atlanta A2 Featuring – Ludacris Money, Hoes & Power A3 Featuring – Manuel Seal, Pimpin Ken, UGK The Dream (Interlude) A4 Featuring – Wanda Sykes Get Some A5 Featuring – Boo & Gotti, R.O.C., Usher A6 Hate (Interlude) Hate Blood A7 Featuring – Freeway, Jadakiss Ballin' Out Of Control B1 Featuring – Nate Dogg Supafly B2 Co-producer – LaMarquis JeffersonFeaturing – Bilal B3 Instructions Interlude Rules Of The Game B4 Featuring – Manish ManProducer – Manish Man C1 Prada Bag (Interlude) Whatever C2 Co-producer – Emanuel DeanFeaturing – Katrina , Nate Dogg, R.O.C., Skeeter Rock, Tigah, Trey Lorenz Let's Talk About It C3 Featuring – ClipseProducer – The Neptunes Yours & Mine C4 Featuring – Jagged Edge Producer – Swizz Beatz Jazzy Hoe's Part 2 D1 Featuring – Backbone, Eddie Cain, Field Mob, Kurupt, Too Short D2 Hot Mama (Interlude) You Bring The Freak Out Of Me D3 Featuring – Da Brat, Kandi D4 The Morning After Rock With Me D5 Featuring – Xscape Credits Co-producer – Bryan-Michael Cox Producer – Jermaine Dupri Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 6 9699-85830-1 6 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Jermaine Instructions (CD, USA & CK 85830 So So Def CK 85830 2001 Dupri Album) Canada -

Snoop Dogg, Vapors

Snoop Dogg, Vapors Can you feel it, nothing can save ya For this is the season of catching the vapors Since I got time, what I'm gonna do Tell ya how it's spreading throughout my crew What you want on Nate Dogg Who sings on my records, 'Never Leave Me Alone' 'Ain't No Fun', now check it Back in the days before Nate Dogg would get it He used to try to holler at this girl named Pam The type of female wit fly Gucci gear She wore a big turkish wole wit a weave in her hair When they tried to kick it, she'd always fess Talkin about baby please she wrought his service stress Since he wasn't no type of big chronic dealer The homie Nate Dogg didn't appeal to her But now he wear boots that match with his suits And push a Lexus Coupe that's extra cheap And now she stop flautin and won't it speakin Be comin round the Pound every single weekend to get his beeper number she be beggin please Dyin for the day to eat these She caught the vapors She caught the vapors I got a little cousin that's kinda plain He bring the heeb wit tha beep for the Dogg Pound gang A mellow type of fellow best laid back But back in the day he wasn't nuthin like that I remember when he used to scrap every day When my auntie would tell him he would never obey He wore his khakis hangin down wit his starks untied And a blue and grey cap that said the Eastside Around my neighborhood tha people treated him bad Said Daz was the worst thing his mom ever had They said he grow up to be nuttin but a gangsta Or be there in jail or some other shaker But now he's grown up to be a surprise D-A-Z got a hit record slangin world wide Now the same people that didn't like him as a child Bought the Dogg Food, Doggfather, and Doggystyle They caught the vapors They caught the vapors I got another homie from tha L-B-C Known ta yall as D.J. -

Feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77

01. 50 Cent - Intro (0:06) 75. Ace Of Base - Life Is A Flower (3:44) 02. 50 Cent - What Up Gangsta? (2:59) 76. Ace Of Base - C'est La Vie (3:27) 03. 50 Cent - Patiently Waiting (feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77. Ace Of Base - Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Mix) 04. 50 Cent - Many Men (Wish Death) (4:16) (3:42) 05. 50 Cent - In Da Club (3:13) 78. Ace Of Base - Beautiful Life (Junior Vasquez Mix) 06. 50 Cent - High All the Time (4:29) (8:24) 07. 50 Cent - Heat (4:14) 79. Acoustic Guitars - 5 Eiffel (5:12) 08. 50 Cent - If I Can't (3:16) 80. Acoustic Guitars - Stafet (4:22) 09. 50 Cent - Blood Hound (feat. Young Buc) (4:00) 81. Acoustic Guitars - Palosanto (5:16) 10. 50 Cent - Back Down (4:03) 82. Acoustic Guitars - Straits Of Gibraltar (5:11) 11. 50 Cent - P.I.M.P. (4:09) 83. Acoustic Guitars - Guinga (3:21) 12. 50 Cent - Like My Style (feat. Tony Yayo (3:13) 84. Acoustic Guitars - Arabesque (4:42) 13. 50 Cent - Poor Lil' Rich (3:19) 85. Acoustic Guitars - Radiator (2:37) 14. 50 Cent - 21 Questions (feat. Nate Dogg) (3:44) 86. Acoustic Guitars - Through The Mist (5:02) 15. 50 Cent - Don't Push Me (feat. Eminem) (4:08) 87. Acoustic Guitars - Lines Of Cause (5:57) 16. 50 Cent - Gotta Get (4:00) 88. Acoustic Guitars - Time Flourish (6:02) 17. 50 Cent - Wanksta (Bonus) (3:39) 89. Aerosmith - Walk on Water (4:55) 18. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND