Movement of Cultural Objects in and Through Finland: an Analysis in a Regional Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Report by Finland

COUNTRY REPORT BY FINLAND Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action (1995) and the Outcome of the Twenty-Third Special Session of the General As- sembly (2000) June 2004 Table of Contents Part I: Overview of achievements and challenges in promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment __________________________________________________________4 Government Programmes since 1995________________________________________________5 Challenges ahead ________________________________________________________________6 Finland as an international actor ___________________________________________________7 Part II: Progress in implementation of the critical areas of concern of the Beijing Platform for Ac- tion and further initiatives and actions identified in the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly _________________________________________________________________________9 Elimination of multiple discrimination – safeguarding equality__________________________9 Challenges to eliminate multiple discrimination_______________________________________9 A. Women and poverty __________________________________________________________10 B. Education and training of women _______________________________________________10 Achievements_________________________________________________________________10 Challenges ahead ______________________________________________________________11 C. Women and health ___________________________________________________________12 Successful examples ___________________________________________________________12 -

Genetic Background of Extreme Violent Behavior

Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 786–792 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/15 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Genetic background of extreme violent behavior J Tiihonen1,2,3,19, M-R Rautiainen3,19, HM Ollila3,4, E Repo-Tiihonen2, M Virkkunen5,6, A Palotie7,8,9,10,11, O Pietiläinen3, K Kristiansson3, M Joukamaa12, H Lauerma3,13,14, J Saarela15, S Tyni16, H Vartiainen16, J Paananen17, D Goldman18 and T Paunio3,5,6 In developed countries, the majority of all violent crime is committed by a small group of antisocial recidivistic offenders, but no genes have been shown to contribute to recidivistic violent offending or severe violent behavior, such as homicide. Our results, from two independent cohorts of Finnish prisoners, revealed that a monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) low-activity genotype (contributing to low dopamine turnover rate) as well as the CDH13 gene (coding for neuronal membrane adhesion protein) are associated with extremely violent behavior (at least 10 committed homicides, attempted homicides or batteries). No substantial signal was observed for either MAOA or CDH13 among non-violent offenders, indicating that findings were specific for violent offending, and not largely attributable to substance abuse or antisocial personality disorder. These results indicate both low monoamine metabolism and neuronal membrane dysfunction as plausible factors in the etiology of extreme criminal violent behavior, and imply that at least about 5–10% of all severe violent crime in Finland is attributable to the aforementioned MAOA and CDH13 genotypes. Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 786–792; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.130; published online 28 October 2014 INTRODUCTION Recently, it was reported that this finding has actually started to 9 Violent crime is a major issue that affects the quality of life even in influence the attitudes on court sentences in the US. -

HENKILÖSTÖEDUT KOULUTUS 2 Monipuolisia& Etuja Ja Koulutusmahdollisuuksia 3 Ostoedut 2018 4 Etuja Ja Bonusta

HENKILÖKUNNAN LEHTI 1/2018 HENKILÖSTÖEDUT KOULUTUS 2 Monipuolisia& etuja ja koulutusmahdollisuuksia 3 Ostoedut 2018 4 Etuja ja bonusta 2018 6 Työ- ja ikämerkkipäivät 7 Työterveyshuolto 8 Sairauskassa ja sopimuspaikat 11 Urapolut 16 Työsuhde- ja loma-asunnot ym. MONIPUOLISIA HOK-ELANTO/HENKILÖKUNNAN OSTOEDUT ETUJA & KOULUTUSMAHDOLLISUUKSIA HOK-Elanto tarjoaa työntekijöilleen monenlaisia henkilös- Vakituisen henkilökuntamme vapaa-ajan tapaturmava- töetuja, sekä konkreettisia ja tuntuvia taloudellisia hyötyjä kuutus ilman korvauskattoa sisältää mm. sairaanhoidon että henkiseen pääomaan ja hyvinvointiin liittyviä etuja. kustannukset, päivärahakorvauksen ja tapaturmaeläk- Osaa eduista voivat hyödyntää myös samassa taloudessa keen. Vakuutus on voimassa kaikkialla maailmassa. asuvat perheenjäsenet. Tällaisia ovat mm. henkilökun- Tämä esite on tietopaketti kaikista HOK-Elannon tarjoa- ta-alennukset HOK-Elannon ja S-ryhmän toimipaikoista, mista henkilöstöeduista ja työhyvinvointiin liittyvistä pal- Vierumäen loma-asuntojen käyttömahdollisuus sekä vuo- veluista. Myös eri toimialojen ja ketjujen urapolut ja niitä sittainen Linnanmäkipäivä. tukevat valmennusohjelmat löydät tästä esitteestä. Tämän vuoden alusta alkaen henkilökuntaetua saa myös Tutustu monipuoliseen tarjontaan ja hyödynnä työnan- Stockmann Herkuista Helsingin keskustassa, Tapiolassa, tajan tarjoamat edut ja kehittymismahdollisuudet! Itiksessä ja Jumbossa. Henkilöstöalennuksen saamiseksi tulee ostokset maksaa henkilökunnan S-Etukortti Visalla, mikä antaa alennuksen Antero Levänen lisäksi -

Country Report for Finland

GROWING INEQUALITIES AND THEIR IMPACTS IN FINLAND Jenni Blomgren, Heikki Hiilamo, Olli Kangas & Mikko Niemelä Country Report for Finland November 2012 GINI Country Report Finland GINI Country Report Finland Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. The Nature of Inequality and Its Development over Time ................................................................ 14 2.1 Has inequality grown? ........................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Household income inequality ........................................................................................ 14 2.1.2 Wealth and debt inequality ........................................................................................... 22 2.1.3 Labour market inequality .............................................................................................. 28 2.1.4 Educational inequality ................................................................................................... 34 2.2 Whom has inequality affected? ............................................................................................ 38 2.3 Interdependence between the inequality components over time ....................................... 43 2.4 Why has inequality -

Nimistöntutkimusta, Komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -Salapoliisiromaaneissa

Nimistöntutkimusta, komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -salapoliisiromaaneissa Milla Juhonen Pro gradu -tutkielma Suomen kieli Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto Toukokuu 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Suomen kielen ja suomalais-ugrilaisten kielten ja kulttuurien mais- teriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Suomen kieli Tekijä – Författare – Author Juhonen, Milla Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Nimistöntutkimusta, komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -salapoliisiromaaneissa Työn laji – Arbetets art – Le- Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages vel year Pro gradu -tutkielma Toukokuu 2020 65 + 3 liitesivua Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielman aiheena on Komisario Palmu -romaanien paikannimistö. Ensisijaisena tavoitteena on analysoida paikannimien roolia fiktiivisen Helsinki-kuvan rakentamisessa. Lisäksi pyritään muodostamaan kokonaisvaltainen käsitys siitä, millaisia paikannimiä romaaneissa esiintyy. Tutkimuksen aineistona on Kuka murhasi rouva Skrofin? (1939) ja Komisario Palmun erehdys (1940) -romaanien paikannimet. Tutkimusaineistossa on yhteensä 58 paikannimeä. Näistä 39 nimeä viittaa Helsingissä sijaitseviin paikkoihin. 12 nimistä on ulkomailla sijaitsevien paikkojen nimiä ja seitsemän taas viittaa muualla Suomessa sijaitseviin paikkoihin. Nimistä 52 on autenttisia paikannimiä ja kuusi fiktiivisiä. Suurin osa nimistä viittaa alueisiin (25 nimeä), kulkuväyliin ja rakennelmiin -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

Exploring Police Relations with the Immigrant Minority in the Context of Racism and Discrimination: a View from Turku, Finland

ISSN 1554-3897 AFRICAN JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY & JUSTICE STUDIES: AJCJS; Volume 1, No. 2, November 2005 EXPLORING POLICE RELATIONS WITH THE IMMIGRANT MINORITY IN THE CONTEXT OF RACISM AND DISCRIMINATION: A VIEW FROM TURKU, FINLAND Egharevba, Stephen Faculty of Law, University of Turku, Finland and Hannikainen, Lauri Faculty of Law, University of Turku, Finland Abstract Citizens and immigrant minorities come into contact with the police in various circumstances, either as witnesses, victims of crime, or even as suspects. The present study is an attempt to examine issues concerning racism and discrimination in police/immigrant relations in Finland under this circumstances, which to our knowledge has not received the academic scholastic investigation it deserves. Furthermore, this is also an attempt to look at police/immigrant everyday interactions to help in understanding this relationship. The research was carried out by means of a questionnaire (the sampled respondents consisting of forty-seven graduating police cadets a day before their graduation from the Police School and six serving police officers) and a semi- structured interview with thirteen police/cadets volunteers. These sources then served as the basis of this analysis Secondly, the participants’ experiences were examined in our attempt to determine whether the relationships were cordial or not. The authors are of the opinion that the experiences of these respondents could help to understand and shed some light on how Exploring Police Relations With The Immigrant Minority In The Context Of Racism And Discrimination: A View From Turku, Finland Egharevba, Stephen and Hannikainen, Lauri these two groups view their relations. The finding indicates some level of ignorance on the part of the police/cadets of the cultural differences between the immigrant minorities and the majority population. -

2ND ANNOUNCEMENT · CALL for ABSTRACTS Invitation

2ND ANNOUNCEMENT · CALL FOR ABSTRACTS Invitation EWMA In cooperation with the Finnish Wound Care Society (FWCS), European Wound Management Association EWMA is pleased to announce the 19th Conference of the The Executive Committee Marco Romanelli, President European Wound Management Association on the theme: Zena Moore, Honorary Secretary & President Elect Luc Gryson, Treasurer Sue Bale, Recorder HEALING, EDUCATING, Council Members Paulo Alves LEARNING and PREVENTING Jan Apelqvist Carol Dealey in wound care Finn Gottrup Marcus Gürgen Maarten J. Lubbers Severin Läuchli The conference gives the participants an opportunity to benefit Sylvie Meaume from high level scientific presentations, network with each E. Andrea Nelson Patricia Price other, exchange data and evaluate clinical practice. Salla Seppänen José Verdú Soriano Rita Gaspar Videira Peter Vowden The conference will be held in Helsinki, Finland at Helsinki Address Exhibition and Convention Centre, which is located in EWMA Business Office Itä-Pasila, a modern urban complex within easy reach c/o Congress Consultants Martensens Allé 8 of the city centre. DK-1828 Frederiksberg C Denmark The participants will therefore not only benefit from the Tel.: +45 7020 0305 Fax: +45 7020 0315 scientific aspect of the conference but also from [email protected] the beautiful location of the conference. www.ewma2009.org We look forward to welcoming you to Helsinki. Sue Bale, EWMA Recorder Marco Romanelli, EWMA President Salla Seppänen, FWCS President Preliminary Programme The programme will consist of plenary sessions, key sessions, work- shops and satellite symposia. The sessions will deal with advancement of education and research in relation to epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis, prevention and management of wounds. -

The Dangerous Offender As a Problem in Finnish Judicature and Society Bruun Kari* University of Tampere, Finland

Open Access Journal of Forensic and Crime Studies RESEARCH ARTICLE ISSN: 2638-3578 The Dangerous Offender as a Problem in Finnish Judicature and Society Bruun Kari* University of Tampere, Finland *Corresponding author: Bruun Kari, University of Tampere, Finland, Tel: + 358415451454, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Bruun Kari (2019) The Dangerous Offender as a Problem in Finnish Judicature and Society. J Forensic Crime Stu 3: 102 Abstract In Finnish judicature, as elsewhere, the dangerousness of offenders has gained increasing attention during the past few decades. The question asked in this study is this: what were the knowledge and belief systems, conditions and struggles, in the judicial and societal spheres in particular, through which dangerousness reached its current status in the context of actor-centric prevention of crime? The research data consisted of government proposals, various documents, literature, and newspaper articles on law drafting as well as assessment, prediction, and conceptions of dangerousness. The analysis was done by examining the data discursively, reaching beyond the textual structure towards language-mediated social construction of reality. The analysis lends support to the notion that presumed dangerousness is a condition that is attached to the offender on the basis of certain indications but that it is not always an omen of severe violence in the future. Although the methods of assessing and predicting dangerousness have shown great progress lately, they still prove controversial in regard to an individual person. Also, the notion of decreasing the risk of offender violence by means of treatment is discernibly less emphasized in Finnish judicature than in most other Western countries. -

WEDNESDAY 8Th 2010

10th Annual Conference of the European Society of Criminology CRIME AND CRIMINOLOGY: FROM INDIVIDUALS TO ORGANIZATIONS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Table of Contents Table of Contents Organizing Comittee ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 List of Participants ................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Panel Session 1 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 79 1. Different perspectives on social perception in the fear of crime : relational concerns and social anxieties .......................................................................................................................... 79 2. The science of Art Crime ................................................................................................................................................ 81 3. Judicial Rehabilitation in Europe – Working Group Community Sanctions ............................................................ 82 4. Youth Violence ................................................................................................................................................................. 83 5. Mafia ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Acta Universitatis Carolinae Studia Territorialia Xxi 2021 1

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE STUDIA TERRITORIALIA XXI 2021 1 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE STUDIA TERRITORIALIA XXI 2021 1 CHARLES UNIVERSITY KAROLINUM PRESS 2021 Editor-in-Chief: PhDr. Jan Šír, Ph.D. (Charles University) Executive Editor: PhDr. Lucie Filipová, Ph.D. (Charles University) Editorial Board: Maria Alina Asavei, Ph.D. (Charles University), Ing. Mgr. Magdalena Fiřtová, Ph.D. (Charles University), doc. RNDr. Vincenc Kopeček, Ph.D. (University of Ostrava), PhDr. Ondřej Matějka, Ph.D. (Charles University), doc. PhDr. Tomáš Nigrin, Ph.D. (Charles University), prof. PhDr. Jiří Kocian, CSc. (Institute of Contemporary His- tory of the Czech Academy of Sciences), doc. PhDr. Luboš Švec, CSc. (Charles Universi- ty), doc. PhDr. Jiří Vykoukal, CSc. (Charles University) International Advisory Board: Prof. dr hab. Marek Bankowicz (Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie), Prof. Dr. Chris- toph Boyer (Universität Salzburg), Prof. Alan Butt Philip (University of Bath), Prof. Iain McLean (Nuffield College, University of Oxford), Soňa Mikulová, Ph.D. (Max-Planck-In- stitut für Bildungsforschung, Berlin), Prof. Dr. Marek Nekula (Universität Regensburg), Prof. Dr. Dietmar Neutatz (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), Prof. James F. Pontuso (Hampden-Sydney College), Prof. Jacques Rupnik (Sciences Po, Paris), Prof. Dr. Wolf- gang Wessels (Universität zu Köln) Website: https://stuter.fsv.cuni.cz © Charles University – Karolinum Press, 2021 ISSN 1213-4449 (Print) ISSN 2336-3231 (Online) CONTENTS Editorial . 7 Articles ................................................................. 9 Memories of the Maya: National Histories, Cultural Identities, and Academic Orthodoxy ................................................. 11 KATHRYN M. HUDSON, JOHN S. HENDERSON Undemocratic History Politics in a Democratic State: Celebrations of Finland’s 100 Years of Independence ..................................... 45 JUHO KORHONEN The Politics of Memory and the Refashioning of Communism for Young People: The Illustrated Guide to Romanian Communism ............ -

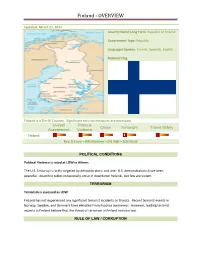

Finland - OVERVIEW

Finland - OVERVIEW Updated: March 21, 2014 Country Name Long Form: Republic of Finland Government Type: Republic Languages Spoken: Finnish, Swedish, English National Flag Finland is a Tier III Country. Significant security measures are necessary. Overall Political Crime Terrorism Travel Safety Assessment Violence Finland Key: (L) Low – (M) Medium – (H) High – (C)Critical POLITICAL CONDITIONS Political Violence is rated at LOW in Athens The U.S. Embassy is rarely targeted by demonstrators, and anti- U.S. demonstrations have been peaceful. Anarchist rallies occasionally occur in downtown Helsinki, but few are violent. TERRORISM Terrorism is assessed as LOW Finland has not experienced any significant terrorist incidents or threats. Recent terrorist events in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark have elevated Finnish police awareness. However, leading terrorist experts in Finland believe that the threat of terrorism in Finland remains low. RULE OF LAW / CORRUPTION Finland - OVERVIEW The Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2013 gave Finland a score of 89, indicating that the country has low levels of corruption. The CPI rates countries by the perceived levels of corruption in the public sector, with the least corrupt receiving a maximum score of 100. CRIME Crime is assessed as LOW Americans are seldom the victims of violent criminal acts, and most violent crimes committed in Finland go almost unnoticed by ordinary Finnish citizens, who more typically fall victim to crimes like burglaries and thefts. Non-violent crimes, such as petty theft and pick-pocketing, increase twofold during the warmer months. Personal robberies occur but are most often during late hours. Violent crime fell six percent in 2013 from 2012, and the number of recorded robberies dropped seven percent.