Towards Shock-Responsive Social Protection: Lessons from the COVID-19 Response in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopia Case Study

Exemplars in Under-5 Mortality: Ethiopia Case Study Dr. Lisa Hirschhorn1,2, Agnes Binagwaho1, Alula M. Teklu3, Laura Drown1, Kelechi Udoh1, Miriam Frisch1, Jovial Thomas Ntawukuriryayo1 1 University of Global Health Equity 2 Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University 3 MERQ Consultancy PLC 28 February 2020 Exemplars in U5M: Ethiopia Case Study 1 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................... 12 1.1 Background on Ethiopia .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Causes of Under-5 and Neonatal Mortality .......................................................................................................................... -

Cultivating Small and Medium-Sized Firms

Cultivating Small and Medium-Sized Firms: Entrepreneurship Development, Gender, and Technology in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ethiopia and Senegal UN TECHNOLOGY UNITED NATIONS TECHNOLOGY BANK FOR LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES This report is written by Halla Thorsteinsdóttir, Jennifer M. Bell and Nandinee Bandyopadhyay, Small Globe Inc., Toronto, Canada. The research upon which the report is based was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa Canada. The production of the report is supported by the United Nations Technology Bank for the Least Developed Countries. Front cover: Women in Bangladesh acquire new skills in the training center. Photo: UN Women Asia and the Pacific Below: Women entrepreneurs and owners of a local Senegalese bakery. Photo: UN Women Africa 3 CONTENTS Executive Summary 05 Acknowledgement 07 List of Acronyms 08 1. Introduction 09 2. Drivers for SME Development 10 3. Government Policies Promoting SME 12 Development 4. Entrepreneurship Ecosystems 16 4.1 Bangladesh 16 4.1.1 Main public sector initiatives in Bangladesh 16 4.1.2 Main multilaterals and donors promoting SME 20 development in Bangladesh 4.1.3 Incubators, accelerators and other actors 21 active in Bangladesh 4.2 Cambodia 23 4.2.1 Main public sector initiatives in Cambodia 23 4.2.2 Main multilaterals and donors promoting SME 26 development in Cambodia 4.2.3 Incubators, accelerators and other actors active 27 in Cambodia 4.3 Ethiopia 30 4.3.1 Main public sector initiatives in Ethiopia 30 4.3.2 Main multilaterals and donors promoting SME development in Ethiopia 31 4.3.3 Incubators, accelerators and other actors active in Ethiopia 32 4 4.4 Senegal 35 4.4.1 Main public sector initiatives in Senegal 35 4.4.2 Main multilaterals and donors promoting SME 37 development in Senegal 4.4.3 Incubators, accelerators and other actors active 40 in Senegal 4.5 Main messages 43 5. -

The First Hundred Days of Novel Corona-Virus Disease 2019 in Ethiopia, 13 March to 21 June 2020: Retrospective Analysis

The First Hundred Days of Novel Corona-virus Disease 2019 in Ethiopia, 13 March to 21 June 2020: Retrospective Analysis Shambel Habebe Watare ( [email protected] ) Ethiopian Public Health Institute https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5554-4027 Zewdu Assefa Edea Ethiopian Public Health Institute Haftom Taame Desta Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fantu Lombamo St Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College Negussie Yohannes Ethiopian Public Health Institute Mulugeta Asefa Ethiopian Public Health Institute Alem Mirkuzie Ethiopian Public Health Institute Diriba Sufa Gemechu Ethiopian Public Health Institute Gizaw Teka Ethiopian Public Health Institute Yohannes Dugasa Feyisa Ethiopian Public Health Institute Kirubel Eshetu Ethiopian Public Health Institute Masresha Tesema Ethiopian Public Health Institute Emmanuel Onuche MUSA World Health Organization Regional Oce for Africa: Organisation mondiale de la Sante pour Afrique Getachew Tollera Ethiopian Public Health Institute Aschalew Abayneh Ethiopian Public Health Institute Ebba Abate Page 1/17 Ethiopian Public Health Institute Research article Keywords: Coronavirus disease, COVID-19, Retrospective, Hundred-days, Shambel, Ethiopia Posted Date: November 24th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-74097/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/17 Abstract Background The Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was originated from Wuhan city, China and spread to almost all countries and territories in the world. Ethiopia reported its rst COVID-19 conrmed case on 13 March, 2020. This study aims to show the epidemiological characteristics of the pandemic in Ethiopia in the rst hundred days, which would help to guide the ongoing national response efforts to control and prevent the spread of the disease through generating scientic evidence. -

East Africa – Desert Locust Crisis FEBRUARY 1, 2021

Fact Sheet #2 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 East Africa – Desert Locust Crisis FEBRUARY 1, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 4 3.6 $38.8 3.3 19 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Number of Locust-Affected People Estimated Acutely Estimated Acres of FAO 2021 Regional Countries Affected Likely to Require Food-Insecure Land Treated for Appeal Extension in East Africa1 Emergency Assistance Population2 Locusts in Ethiopia, for Response in Kenya, and Somalia East Africa FAO – December 2020 FAO – December 2020 IPC – December 2020 FAO – January 2021 FAO – December 2020 • Swarms that formed in eastern Ethiopia and central Somalia have been migrating to southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya since December. • Locusts continue to breed along the Red Sea coastal areas and in northern Somalia. • Two USAID/BHA-contracted spray aircraft have treated nearly 175,700 acres of locust infested areas since November and have been redeployed to southern Ethiopia for additional operations. • Control operations have prevented 2.9 million metric tons (MT) of crop loss at harvest time since January 2020, safeguarding the food security of 19.6 million people and protecting grazing areas for the livestock of 1.4 million households. TOTAL USAID HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA3 $25,770,961 For the East Africa Desert Locust Crisis Response in FYs 2020–2021 USAID/Uganda $379,862 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 5 Total $26,150,823 1 Figure includes East African countries included in the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)’s revised regional response plan as of late December: Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, and Sudan. -

Download the Report

Project Leads: Nicola Barrach-Yousefi and Althea Middleton-Detzner Project Team: Nicola Barrach-Yousefi, Althea Middleton-Detzner, Meklite Balcha, Will Ferroggiaro Partner Organizations and Collaborators: Centre for the Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD) | www.cardeth.org Destiny Ethiopia Project | www.destinyethiopia.com Editorial Design: Kirsten Ankers | Citrine Sky Design Front and Back Cover Design: Cesar Manuel Leon Osorio | www.PotencialPuro.com Copy Editor: Gregory Payne About the Lead Author: Nicola Barrach-Yousefi has over 15 years of experience working in human rights and with civil society worldwide. She specializes in collaborating with movements and human rights defenders to design field programs and research around hate speech, human rights, civil resistance and advocacy. She is the Founder and Executive Director of Human Rights Connected, a networked organization focused on mainstreaming understanding of strategic nonviolent action and international human rights law. She also serves as Senior Advisor for Civic Initiatives at the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC) and as Senior Advisor for the Hate Speech program at the PeaceTech Lab. She is the lead author for the Cameroon and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) lexicons. She serves as a consultant for the UN, USIP, and other international organizations. Table of Contents Purpose ..................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................. -

Linear Regression Model for Predictions of COVID-19 New

Linear Regression Model for Predictions of COVID- 19 New Cases and New Deaths Based on May/June Data in Ethiopia Alemayehu Sir Argawu ( [email protected] ) Ambo University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4444-0513 Research Article Keywords: COVID-19 New Cases, New Deaths, Number of Days, Laboratory Tests, New Recoveries, Correlation Coecient, Linear Regression Model Posted Date: August 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-61667/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Linear Regression Model for Predictions of COVID-19 New Cases and New Deaths Based on May/June Data in Ethiopia By Alemayehu Siffir Argawu (MSc) [email protected] [email protected] Department of Statistics, Ambo University Ambo, Ethiopia Introduction: On the 15th of June 2020, we have 7,984,067 total COVID-19 cases, globally and 435,181 deaths. Ethiopia was ranked 2nd and 15th in the table by 176 new cases and by 3,521 total new cases from African countries. Then, this study aimed to predict COVID-19 new cases and new deaths based on May/June data in Ethiopia using a linear regression model. Methods: In this study, I used Pearson’s correlation analysis and the linear regression model to predict COVID-19 new cases and new deaths based on the available data from 12th May to 10th June 2020 in Ethiopia. Results: There was a significant positive correlation between COVID-19 new cases and new deaths with different related variables. In the multiple linear regression model, variables such as the number of days, the number of new laboratory tests, and the number of new cases from AA city significantly predicted the COVID-19 new cases. -

Human Rights Responsibilities of States in Armed Conflicts Case of Eritrean Involvement in Ethiopia’S Tigray War

Human Rights Responsibilities Of States In Armed Conflicts case of Eritrean involvement in Ethiopia’s Tigray war Freweyini Hadush Kebede Spring semester of 2021 Independent written essay within the field of constitutional law and human rights, 15 credits Master’s programme in constitutional law and human rights, 60 hp Supervisor: Elizabeth Perry Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... 3 1.Introduction .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Statement of the problem .......................................................................................... 6 1.3 Purpose of the study ................................................................................................. 6 1.4 Research question ..................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 7 1.6 Scope of the study .................................................................................................... 8 2. Nature of the conflict; is it armed conflict or law enforcement operation? ............... 8 2.1Army conflict vs. law enforcement operation ........................................................... -

The COVID-19 Pandemic in the IGAD Region: Impact on the Health and Economy Vol

The COVID-19 Pandemic in the IGAD region: Impact on the Health and Economy Vol. I Horn Economic and Social Policy Institute (HESPI): Pillar 2 An assessment of the health and economic impact on the HoA countries1 Disclaimer: This document benefited from comments and feedback by a discussant and participants of the virtual validation workshop. The opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the AUHIP or the RWG. November, 2020 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia www.hespi.org 1 This research work was financially supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Royal Danish Embassy in Addis Ababa. The Covid-19 Pandemic in the IGAD Region: Impact on Health and the Economy2 Abstract The Covid crisis has cast its dark shadow in the IGAD region at the worst time as it came on top of the problems of weak or fragile states, lack of capacity, wide spread poverty and food insecurity, conflicts, and the desert locust invasion. Many of the member countries are also under major economic difficulties and have significant vulnerable populations, and large numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees. In addition to persistent fiscal and balance of payment deficits, debt burden, high inflation, foreign exchange shortage, and high unemployment (in the absence of social security), they are facing multiple shocks such as recurrent drought, floods, and conflict and common vulnerabilities such as environment degradation, land pressure, food insecurity malnutrition, limited access to health services and sanitation. Moreover, the region has an estimated 30 million pastoral population that move across borders, hence are less reachable with awareness and protection measures. -

The Sidama's Quest for Self-Rule: a Study of the Referendum on Regional

The Sidama’s quest for self-rule: A study of the referendum on regional statehood By Kjetil Tronvoll, with Filata Boroje and Kairedin Tezera European Institute of Peace January 2020 1 About the authors Kjetil Tronvoll is professor of peace and conflict studies at Bjørknes University College (Norway) and Managing Director of Oslo Analytica. Tronvoll has a PhD in social anthropology from LSE. He has researched developments in the Horn of Africa for close to 30 years and published extensively on issues of politics and identity, democratisation, human rights, and conflicts. Tronvoll has served as an advisor to various national and multilateral agencies on processes of peace, human rights, and democracy in Ethiopia and elsewhere in Eastern Africa. Filata Gigiso Boroje is Lecturer of Law and is currently serving as the Head of School of Law and Hawassa University in Ethiopia. Trained as a lawyer (LL.B) Filata also holds an MA in Governance and Development Studies from Hawassa University. His research focuses on good governance and human rights. Kairedin Tezera Adera is assistant professor of social anthropology at Addis Ababa University. He has his PhD in social anthropology from Bayeruth University (BIGSAS) (Germany). Kairedin has published books and articles on the Silte culture and history, and legal pluralism in southern Ethiopia. About Oslo Analytica Oslo Analytica is an independent research and consultancy company, offering bespoke analysis and programming to governmental and multilateral agencies, NGOs, and the private sector. About the European Institute of Peace The European Institute of Peace (EIP) is an independent body that partners with European states and the European Union to craft strategic and effective approaches to conflict prevention, resolution, dialogue, and mediation. -

HORN-Bulletin-Vol-III-•-Iss-IV-•-July-August-2020.Pdf

Volume III Issue IV July-August 2020 Bulletin The HORN Bulletin is a bi- Historical monthly publication by the HORN Talking Nile: Institute. It contains thematic articles mainly on issues affecting Aspects, Current Concerns, the Horn of Africa region. and the Stalemate in Grand INSIDE Talking Nile: Historical Aspects, 1 Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Current Concerns, and the Stalemate in GERD Negotiations Negotiations Human Rights and COVID-19 11 Responses in the Horn of Africa By Aleksi Ylönen, Ph.D. Burundi in Transition: Nkurunziza’s 20 Legacy and Priority Areas for the Incoming Administration Abstract The Double Edged Sword: China- 29 The iconic Nile River is both historically important and currently significant Kenya Relations in the Wake of COVID-19 Pandemic for the peoples inhabiting territories surrounding it. Ensuring continued access to Nile’s water resources has for a long time been an issue of concern About the HORN Institute especially to those whose livelihoods depend on it in the downstream territories. With independence, securing a sufficient supply of Nile water The HORN International Institute became a national security issue for Egypt and it became the most for Strategic Studies is a non- interested party in the Nile affairs. For years, Egypt, and Sudan as its junior profit, applied research, and partner, worked as the leading states in studying and exploiting the Nile policy think-do tank based water resources. However, with its ambitious dam project on the Blue Nile in Nairobi, Kenya. Its mission which contributes crucially to Nile’s overall flow, Ethiopia rapidly became a is to contribute to informed, contender in Nile affairs. -

World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020

World Economic Situation and Prospects asdf United Nations New York, 2020 Africa GDP Growth GDP Growth projected 3.5 3.2 2.9 2.9 3.0% 2.7 total 2.0% 1.1 1.0% 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.1 0.0% per 2017 2018 capita 2019 2020 2021 Trade structure 2018 GDP per capita Export Structure 2019 2018 World $11,300 7% Developed Other economies $47,100 19% Manufactured Economies $7,200 goods 17% in transition Services Developing economies $5,500 Western Asia $12,500 36% 12% Food & East Asia Fuels $9,000 9% agriculture Latin America $8,000 Ores & and the Caribbean metals South Asia $2,100 Africa $2,000 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. The map represents countries and/or territories or parts thereof for which data is available and/or analysed in World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020. The shaded areas therefore do not necessarily overlap entirely with the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. Chapter III. Regional developments and outlook 121 Developing economies Africa: growth rates are insufficient for meaningful development progress • GDP growth is inching up in Africa but is inadequate to meet development needs in most subregions. • In GDP per capita terms, the continent has experienced a decade of near stagnation. • Rising numbers of people in extreme poverty, elevated public debt and the lack of export diversification are key medium-term challenges. -

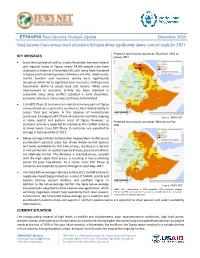

December 2020 Food Security Crisis Across Much of Eastern Ethiopia Drives Significantly Above Normal Needs for 2021

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook Update December 2020 Food security Crisis across much of eastern Ethiopia drives significantly above normal needs for 2021 Projected food security outcomes, December 2020 to KEY MESSAGES January 2021 • Since the outbreak of conflict in early November between federal and regional forces in Tigray, nearly 54,000 people have been displaced to Sudan as of December 26, with many likely displaced in Tigray and to bordering areas of Amhara and Afar. Additionally, market function and economic activity were significantly disrupted, which led to significant price increases, limiting many households' ability to access food and income. While some improvement in economic activity has been reported in accessible areas since conflict subsided in early December, economic activity in many areas continues to be limited. • Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected in many parts of Tigray as households are expected to continue to have limited ability to access food and income. In the absence of humanitarian assistance, Emergency (IPC Phase 4) outcomes are likely ongoing Source: FEWS NET in some central and eastern areas of Tigray; however, as Projected food security outcomes, February to May economic activity is expected to improve as the conflict remains 2021 at lower levels, Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected to emerge in February/March 2021. • Below-average October to December hagaya/deyr rainfall across southeastern pastoral areas has driven below-normal pasture and water availability for this time of year, resulting in a decline in milk production. In southern pastoral areas, pasture conditions are relatively normal. The decrease in livestock prices, coupled with the high staple food prices, is resulting in low purchasing power for poor households.