The Effect of Tranexamic Acid in Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Tranexamic Acid in the Treatment of Residual Chronic Subdural Hematoma: a Single-Centre, Observer-Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial (Trace)

TRANEXAMIC ACID IN THE TREATMENT OF RESIDUAL CHRONIC SUBDURAL HEMATOMA: A SINGLE-CENTRE, OBSERVER-BLINDED, RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL (TRACE) by Adriana Micheline Workewych A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Adriana Micheline Workewych 2018 TRANEXAMIC ACID IN THE TREATMENT OF RESIDUAL CHRONIC SUBDURAL HEMATOMA: A SINGLE-CENTRE, OBSERVER-BLINDED, RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL (TRACE) Adriana Micheline Workewych Master of Science Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2018 ABSTRACT Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is a frequent consequence of head trauma, particularly in older individuals. Given the aging of populations globally, its incidence is projected to increase substantially. Hyperfibrinolysis may be central to CSDH enlargement by causing excessive clot degradation and liquefaction, impeding resorption. The only current standard treatment for CSDH is surgery, however, up to 31% of residual hematomas enlarge, requiring reoperation. Tranexamic acid (TXA), an antifibrinolytic medication that prevents excessively rapid clot breakdown, may help prevent CSDH enlargement, potentially eliminating the need for repeat surgery. To evaluate the feasibility of conducting a trial investigating TXA efficacy in residual CSDH, we conducted an observer-blinded, pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT). We showed this trial was feasible and safe, reporting only minor to moderate AEs, and an attrition rate of 4%. The results from this study will inform the conduct of a double-blinded RCT investigating TXA efficacy in post-operative CSDH management. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Michael Cusimano, my mentor for nearly six years. You have always given me more opportunity than I could have ever hoped for – I could not ask for a more dedicated teacher. -

No Benefit of Hemostatic Drugs on Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Cirrhosis

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2020, Article ID 4097170, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4097170 Research Article No Benefit of Hemostatic Drugs on Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Cirrhosis Yang An,1,2 Zhaohui Bai,1,2 Xiangbo Xu,1,2 Xiaozhong Guo ,1 Fernando Gomes Romeiro ,3 Cyriac Abby Philips,4 Yingying Li,5 Yanyan Wu,1,6 and Xingshun Qi 1 1Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (formerly General Hospital of Shenyang Military Area), Shenyang 110840, China 2Postgraduate College, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, Shenyang 110016, China 3Department of Internal Medicine, Botucatu Medical School, UNESP-Univ Estadual Paulista. Av. Prof. Mário Rubens Guimarães Montenegro, s/n Distrito de Rubião Jr, Botucatu, Brazil 4The Liver Unit and Monarch Liver Lab, Cochin Gastroenterology Group, Ernakulam Medical Center, Kochi, 682028 Kerala, India 5Department of Gastroenterology, The First People’s Hospital of Huainan, Huainan 232007, China 6Postgraduate College, Jinzhou Medical University, Jinzhou 121001, China Correspondence should be addressed to Xingshun Qi; [email protected] Received 28 February 2020; Revised 25 May 2020; Accepted 1 June 2020; Published 27 June 2020 Academic Editor: Hongqun Liu Copyright © 2020 Yang An et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background and Aims. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) is one of the most life-threatening emergency conditions. Hemostatic drugs are often prescribed to control AUGIB in clinical practice but have not been recommended by major guidelines and consensus. -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Multiple Technology Appraisal Avatrombopag and Lusutrombopag

Multiple Technology Appraisal Avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure [ID1520] Committee papers © National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2019. All rights reserved. See Notice of Rights. The content in this publication is owned by multiple parties and may not be re-used without the permission of the relevant copyright owner. NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE MULTIPLE TECHNOLOGY APPRAISAL Avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure [ID1520] Contents: 1 Pre-meeting briefing 2 Assessment Report prepared by Kleijnen Systematic Reviews 3 Consultee and commentator comments on the Assessment Report from: • Shionogi 4 Addendum to the Assessment Report from Kleijnen Systematic Reviews 5 Company submission(s) from: • Dova • Shionogi 6 Clarification questions from AG: • Questions to Shionogi • Clarification responses from Shionogi • Questions to Dova • Clarification responses from Dova 7 Professional group, patient group and NHS organisation submissions from: • British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL) The Royal College of Physicians supported the BASL submission • British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) 8 Expert personal statements from: • Vanessa Hebditch – patient expert, nominated by the British Liver Trust • Dr Vickie McDonald – clinical expert, nominated by British Society for Haematology • Dr Debbie Shawcross – clinical expert, nominated by Shionogi © National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2019. All rights reserved. See Notice of Rights. The content in this publication is owned by multiple parties and may not be re-used without the permission of the relevant copyright owner. MTA: avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure Pre-meeting briefing © NICE 2019. -

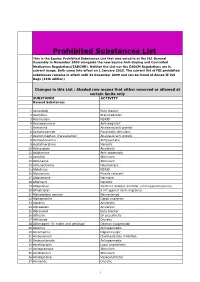

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

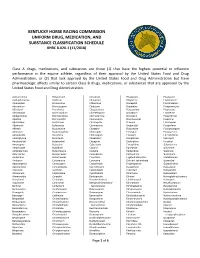

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

Supplement II to the Japaneses Pharmacopoeia Fourteenth Edition

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notiˆcation No. 461 In accordance with the provisions of Article 41, Paragraph 1 of the Pharmaceutical AŠairs Law (Law No. 145, 1960), we hereby revise a part of the Japanese Phar- macopoeia (Ministerial Notiˆcation No. 111, 2001) as follows, and the revised Japanese Pharmacopoeia shall come into eŠect on January 1, 2005, [including dele- tion from O‹cial Monographs fro Part II in The Japanese Pharmacopoeia, Four- teenth Edition of the articles of Absorbent Cotton, Puriˆed Absorbent Cotton, Sterile Absorbent Cotton, Sterile Puriˆed Absorbent Cotton and Absorbent Gauze and Sterile Absorbent Gauze (hereinafter referred to as ``sanitary materials'')]. Provi- so: With respect to the drugs which are included in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``the old Japanese Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those included in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed with this notiˆcation published (hereinafter referred to as ``the new Japanese Phar- macopoeia'')] and those which are approved as of January 1, 2005 pursuant to the provisions of Article 14, Paragraph 1 of this Law (including cases where it shall apply mutatis mutandis under Article 23 of this Law; the same hereinafter) [including the drugs designated as those exempted from approval (hereinafter referred to as ``the drugs exempted from approval'') among the drugs etc. designated by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare as those exempted from manufacturing or import approval pursuant to the provisions of Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Pharmaceutical AŠairs Law (Ministerial Notiˆcation No. 104, 1994), the standards established in the old Japanese Pharmacopoeia (limited to the standards for the relevant drugs) shall be recognized, up to June 30, 2006, as the standards established in the new Japanese Pharmacopoeia. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0181054A1 Nishibe Et Al

US 2005O181054A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0181054A1 Nishibe et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 18, 2005 (54) PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITION FOR (30) Foreign Application Priority Data APPLICATION TO MUCOSA Apr. 21, 1998 (JP)................................ 10-110887(PAT) (75) Inventors: Yoshihisa Nishibe, Tokyo (JP); Wataru Apr. 21, 1998 (JP)................................ 10-110888(PAT) Kinoshita, Tokyo (JP); Hiroyuki Kawabe, Tokyo (JP) Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl." ........................... A61K 9/24; A61K 31/56; Correspondence Address: A61K 31/70; A61K 31/205 SUGHRUE MION, PLLC (52) U.S. Cl. ............................ 424/473; 514/23: 514/169; 2100 PENNSYLVANIAAVENUE, N.W. 514/554 SUTE 800 WASHINGTON, DC 20037 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: TEIJIN LIMITED The present invention provides a pharmaceutical composi tion for application to the mucosa to be used in drug therapy (21) Appl. No.: 11/102,760 comprising a water-insoluble and/or water-low Soluble Sub stance, a medicament, and an aqueous medium, and having (22) Filed: Apr. 11, 2005 an osmotic pressure of less than 290 mOsm. This compo Sition is Superior over conventional pharmaceutical compo Related U.S. Application Data Sitions for application to the mucosa, due to efficient and high permeability to the blood at the mucosa. The present (63) Continuation of application No. 10/201,303, filed on invention further provides a pharmaceutical composition for Jul. 24, 2002, which is a continuation of application application to the mucosa comprising a hemostatic agent and No. 09/446,276, filed on Dec. 21, 1999, filed as 371 a medicament. This composition is Superior over conven of international application No. -

Tranexamic Acid and Total Knee Arthroplasty

Central Annals of Orthopedics & Rheumatology Review Article *Corresponding author Ran Schwarzkopf , Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of California Irvine, Orange, 101 The City Drive South, Pavilion III, Building 29, Orange, CA, 92868, Tel: Tranexamic Acid and Total Knee 714-456-5759, USA, Email: [email protected] Submitted: 24 September 2013 Arthroplasty Accepted: 30 September 2013 Published: 02 October 2013 Phuc (Phil) Dang and Ran Schwarzkopf* Copyright Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of California Irvine, USA © 2013 Dang and Schwarzkopf OPEN ACCESS Abstract Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most commonly performed elective orthopaedic procedures in the United States. TKA provides significant pain relief and improvement in quality of life. However, TKA surgery has been shown to have significant blood loss that sometimes requires blood transfusions. Transfusion of blood products is not a benign procedure and is associated with many risks such as; periprosthetic joint infection, lengthen hospital stay, and increased cost for the patient and payers. Tranexamic acid (TXA), an inhibitor of fibrinolysis, has been used in TKA to control blood loss. Because of the TXA’s mode of action, there have been longstanding concerns about the possibilities of adverse effects, such as thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and renal failure. Multiple studies and review articles have shown that tranexamic acid is efficacious and does not significantly increase the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and renal failure. Intravenous and intra- articular (topical) TXA injection has been shown to be efficacious in controlling blood loss and transfusion requirement, with increasing concentration being more efficacious. Common dosage of IV TXA is 10mg/kg prior to tourniquet inflation and during closure.