Forensic Toxicology – Robert WENNIG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master of Science in Biomedical Forensic Sciences Master of Science in Biomedical Forensic Sciences

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOMEDICAL FORENSIC SCIENCES MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOMEDICAL FORENSIC SCIENCES Program Overview The M.S. in Biomedical Forensic Sciences trains individuals for a variety of disciplines applied to crime scene investigation and evidence analysis. The only program of its kind based at a major medical center, students benefit from unique opportunities to engage with forensic science practitioners, examine cadavers, utilize extensive laboratory and library resources and access a 32-acre outdoor forensic science research facility that includes: • A crime scene house • Open fields, wooded areas and a cranberry bog • A decomposition field In addition, the University’s medical campus, home to Boston’s largest research park, is very close to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for Massachusetts as well as the Boston Police Department’s Crime Laboratory. Program Highlights: Through the class curriculum, laboratory • Only program of its kind based at a medical school, experiments, thesis research and mentoring, and one of the few forensic science graduate programs I had many opportunities to learn from professors offered in New England who have practical experiences and are active • Emphasis on biomedical specialties including toxicology, members in their fields. pathology, DNA analysis and bloodstain pattern analysis - Drew Horsley, Class of 2014 • Access to state-of-the-art laboratory equipment used in forensic DNA analysis, drug chemistry, trace analysis, and microscopy • Coursework in criminal law including a mock court -

Primer on Forensic Toxicology

1 OSAC’s purpose is to strengthen the nation's use of forensic science by providing technical leadership necessary to facilitate the development and promulgation of consensus-based documentary standards and guidelines for forensic science, promoting standards and guidelines that are fit-for-purpose and based on sound scientific principles, promoting the use of OSAC standards and guidelines by accreditation and certification bodies, and establishing and maintaining working relationships with other similar organizations. 2 The six subcommittees of the Chemistry/Instrumental Analysis SAC include Fire Debris and Explosives, Geological Materials, Gunshot Residue, Materials (Trace), Seized Drugs and Toxicology. 3 This resource is intended to provide a brief overview, or the “what”, “why”, “where”, and “how”, of the field of Forensic Toxicology. 4 Toxicology is the study of drugs and chemicals on biological systems. Toxicology relies on information from numerous scientific and social disciplines as well as engineering and statistics. 5 Forensic toxicology deals with the application of toxicology to cases and issues where adverse effects of the use of impairing, toxic and lethal concentrations of drugs have administrative or medicolegal consequences, and where the results are likely to be used in a legal setting. 6 Other career opportunities exist in hospitals, universities, and industry. 7 Paracelsus is often credited with one of the original conceivers of toxicology. Manly Hall, a famous author of the 19th Century called him "the precursor of chemical pharmacology and therapeutics and the most original medical thinker of the sixteenth century.“ A principle tenet of forensic toxicology is that the “dose makes something a poison”. For example, water is generally a safe and essential beverage all living organisms require to live, but if taken in an excessive amount this can interfere with a body’s chemistry and create a toxic environment. -

Forensic Toxicology in Death Investigation

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. CHAPTER 5 Forensic Toxicology in Death Investigation Eugene C. Dinovo, Ph.D., and Robert H. Cravey Forensic toxicology is a highly specialized States, warrant an official investigation by the area of forensic science which requires exper coroner or medical examiner to determine the tise in analytical chemistry, pharmacology, cause of death. The resolution of many legal biochemistry, and forensic investigation. The questions depends on the official pronounce practicing forensic toxicologist is concerned ment of the cause of death. The settlement of not only with the isolation and identification insurance claims often rests on the pro of drugs and other pOlsons from tissues, but nouncement of the death investigator. Accu also with the interpretation of his findings for racy in determining the cause of death depends the medical examiner, coroner, or other legal on the cooperation and free flow of informa authority. tion among all members of the medicolegal In our modern drug-oriented society the investigative team: the police homicide need for the services of a toxicologist is clear. investigator, the medical examiner's investi The benefits received from medication are so gator, the forensic pathologist, the forensic well publicized that society tends to minimize toxicologist, and the medical examiner. the dangers and pitfalls. The American people The homicide investigator is usually the spend over $9 billion a year on drugs. In first to view the scene and, if he is properly 1971, the public spent approximately $5% bil trained, it is he who maintains the scene lion on prescription drugs and about $3'12 bil undisturbed for the medical examiner whom lion for over-the-counter medications (Arena he calls. -

73Rd Aafs Annual Scientific Meeting

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF FORENSIC SCIENCES 73RD AAFS ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING PROGRAM • FEBRUARY 2021 WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to the 73rd American Academy of Forensic Sciences Annual Scientific Meeting. We are 100% virtual this year and it is my pleasure and excitement to greet each and every one of you. While we could not be in Houston, we have planned a jammed packed week of science, collegial interactions, collaborations, learning, social networking, and just plain fun! The Academy has nearly 6,500 members representing 70 countries. We usually meet annually in the U.S., but this year we are meeting virtually and worldwide for the first time. I cannot wait to see how many locations across the globe will be represented by our attendees. Jeri D. Ropero-Miller, PhD 2020-21 AAFS President Our meeting theme this year, One Academy Pursuing Justice through Truth and Evidence, has fueled the culture of the Academy since its inception. It has also encouraged more than 1,000 presentations for this week with over 560 oral, more that 380 posters, and countless presenters in the 18 workshops, and special sessions. The Exhibit Hall will be accessible to attendees the entire week. Don’t miss out on all the latest products and technology available to the forensic science industry. You also will want to participate in the Gamification activity by going on a virtual scavenger hunt to earn points towards winning some fun prizes. Don’t forget to visit the online AAFS store between sessions for your chance to purchase meeting apparel. I cannot thank everyone enough for all the effort, dedication, and support for making this virtual event memorable for all. -

Forensic Toxicology: Career Choices and Development Karen Sco� Ph.D, MRSC, Michele (Shelly) Merves Ph.D., DABFT Barry Logan Ph.D, DABFT C

Forensic Toxicology: Career Choices and Development Karen ScoU Ph.D, MRSC, Michele (Shelly) Merves Ph.D., DABFT Barry Logan Ph.D, DABFT C. Chem., C. Sci. Assistant Laboratory Director- 2013-14 President, AAFS Associate Professor, Toxicology NMS Labs & Forensic Science Pinellas County Forensic Lab Center for Forensic Science Research Arcadia University Largo, FL and Educaon Glenside, PA Willow Grove, PA Forensic Toxicology Answers the QuesNon: Did Alcohol or Drugs, Cause or Contribute to, this Person’s Death or Intoxicaon? BL PracNce Areas • Human performance – Driving – Post Crash – Drug Facilitated Sexual Assault • Death InvesNgaon • Regulated • High throughput vs less casework/complex (interpretaon) BL Forensic Toxicology Analy&cal Interpreve SM AnalyNcal Toxicology • Understanding the chemistry of the analyte. • Knowing the capabiliNes of various analyNcal plaorms (i.e. how instruments work). • Understanding Quality Management requirements. • Understanding data evaluaon and assessment. • Applying insight into working with problemac specimens. • Understanding method development and opNmizaon. • Performing method validaon. SM InterpreNve Toxicology • Understanding the source of the sample and its limitaons. • Understanding how the result was obtained and its limitaons. • Thorough familiarity with the published literature on drug concentraons. • Knowing the therapeuNc, toxic and potenNally fatal outcomes associated with different toxins. • Relang laboratory findings to invesNgave, autopsy, and cogniNve and behavioral findings. SM Key Competencies -

Handbook of Forensic Medicine

Handbook of Forensic Medicine Handbook of Forensic Medicine Edited by Burkhard Madea Institute of Forensic Medicine University of Bonn Bonn, Germany This edition first published 2014 © 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Wiley Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing. Registered office: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offices: The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Tox Part 1.Pdf

1 Agree or Disagree? • "All substances are poisons; there are none which is not a poison. The right dose differentiates a poison and a remedy.“ – Paracelsus Swiss-German Physician (1493-1541) 2 Central Focus Students can explain how forensic toxicologists use components of chemistry, biology, and medicine to interpret and justify their toxicology results from bodily tissues/fluids. Students can explain the proper techniques used to identify toxins in the body and describe why toxins have different effects on different people. 3 Learning Standards Ga. SFS3. Students will analyze the use of toxicology in forensic investigations. a. Classify toxins and their effects on the body. c. Evaluate forensic techniques used to isolate toxins in the body 4 Day 1 Essential Questions • What is the difference between the type(s) of evidence that is analyzed by a forensic chemist versus a forensic toxicologist during a criminal investigation? • Why is toxicology important to criminal investigations? • How is lethality of a drug/poison determined? 5 Learning Targets. I can… • SFS1a – LK1: Match historical forensic scientists with their role in crime scene investigations • SFS3a – LK3: Describe how toxicology applies to criminal investigations. • SFS3a – LR6: Compare/contrast intoxicants, poisons, and toxins • SFS3a – LR7: Classify toxins and their effects on the body • SFS3a – LR8: Categorize toxin/poison exposure as intentional, deliberate, or accidental • SFS3a – LK4: Explain LD50 and how it applies to forensic toxicology 6 Toxicology • Mathieu Orfila -

Forensic Toxicology MODULE No.8: Organic Poisons: Animal Poisons

SUBJECT FORENSIC SCIENCE Paper No. and Title PAPER No.10: Forensic Toxicology Module No. and Title MODULE No.8: Organic Poisons- II: Animal Poisons Module Tag FSC_P10_M8 FORENSIC SCIENCE PAPER No.10: Forensic Toxicology MODULE No.8: Organic Poisons: Animal Poisons TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcome 2. Introduction to Animal Poisoning 3. Forensic Issues 4. Categorization of Venomous Animals 4.1 Vertebrates 4.1.1 Reptiles 4.1.2 Fishes 4.1.3 Amphibians 4.1.4 Birds 4.2 Non- Vertebrates 4.2.1 Arthropods 4.2.2 Arachnids 4.2.3 Cnidaria (or Coelenterates) 4.2.4 Molluscs 5. Summary FORENSIC SCIENCE PAPER No.10: Forensic Toxicology MODULE No.8: Organic Poisons: Animal Poisons 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to know about – The toxins of Animal origin. General introduction of certain animal toxins Forensic significance of animal poisoning 2. Introduction to Animal Poisoning Largely it talks about the poisons originated from living organisms which are obviously animals. While there is so much diversity in the animal kingdom, the methods of predation and self-protection is varies from species to species. Similarly, some animals use poisons as a weapon of predation or self-defence or both. Snakes are the most popular among these type creatures besides other known venomous organisms like, fishes, insects, etc. In India, deaths as a result of snake-bite are mainly accidental in nature. Venoms used in an offensive posture are generally associated with the oral pole, as in the snakes and spiders, while those used in a defensive function are usually associated with the aboral pole or with spines, as in the stingrays and scorpion fishes. -

Crime-Scene-Technician-Curriculum-Guide

© A Curriculum Guide for Contextualized Instruction in Workforce Readiness Crime Scene Technician The Literacy Institute at Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Adult Learning Resource Center 3600 W Broad St. Ste 112 Richmond, VA 23230 www.valrc.org Southwest Virginia Community College 724 Community College Road Cedar Bluff, VA 24609 1 www.pluggedinva.com This work by Virginia Commonwealth University is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. PluggedInVA© is a project of the Virginia Adult Learning Resource Center at Virginia Commonwealth University. PluggedInVA© has received funds from the Governor's Productivity Investment Fund, The Chancellor's Elearning Enhancement & Development Grant, the Virginia Department of Education Office of Adult Education & Literacy, the Virginia Community College System, the Virginia Employment Commission, and the Department of Labor. This curriculum guide was developed as part of a Department of Labor Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training grant to Southwest Virginia Community College. 2 October, 2013 Table of Contents I. PluggedInVA Introduction and Project Rationale II. PluggedInVA Curriculum Framework III. Instructional Schedules Monthly Objectives Weekly Instructional Template IV. Capstone Project Project Description Project Planning Template V. Instructional Approaches and Strategies VI. Materials and Resources Appendices i. Sample Instructional Activities ii. College Survival Resources iii. Online Collaboration Tool Example v. Phlebotomy Classroom Activities and Resources A. Career Assessment B. Ethics and Justice C. Mythbusting in Forensic Science D. What is Leadership? And What is Its Value? Information about the PluggedInVA project, including resources for planning and implementation, are available on the PluggedInVA website. 3 I. Introduction PluggedInVA is a career pathways program that prepares adult learners with the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in postsecondary education, training, and high-demand, high-wage careers in the 21st century. -

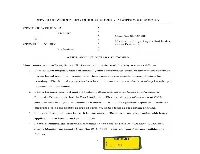

Affidavit of Stuart H. James

STATE OF WISCONSIN : CIRCUIT COURT : MANITOWOC COUNTY STATE OF WISCONSIN, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Case No. 05-CF-381 V. ) ) Honorable Judge Angela Sutkiewicz, STEVEN A. AVERY, ) Judge Presiding ) Defendant. ) AFFIDAVIT OF STUART H. JAMES Now comes your affiant, Stuart H. James, and under oath hereby states as follows: 1. I am of legal majority and can truthfully and competently testify to the matters contained herein based upon my personal knowledge and to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty. The factual statements herein are true and correct to the best of my knowledge, information, and belief. 2. I am a forensic scientist and bloodstain pattern analyst with James and Associates Forensic Consultants, Inc. in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. A copy of my current CV is attached and incorporated herein as Exhibit A. All of the opinions expressed herein are expressed to a reasonable degree of certainty in the field of bloodstain analysis. 3. In my professional experience, it is extremely difficult to clean blood stains with heavy applications of bleach and paint thinner. 4. I have examined the following materials in the case of State of Wisconsin v. Steven A. Ave,y, Manitowoc County Case No. 05-CF-381, received from Attorney Kathleen T. Zellner: EXHIBIT 1 6 a. Photographs of RAV -4 vehicle b. Photographs of bone fragments c. Photographs of burn area behind garage d. Photographs of burn barrel contents e. Photograph of blood sample container f. Video and photographs of blood tube packaging g. Photographs of garage and contents h. Photograph of burned cell phone 1. Photographs of blood stain on Steven A very' s bathroom floor J. -

Toxicological Analyzes and Its Use in Forensic Science

Forensic Research & Criminology International Journal Research Article Open Access Toxicological analyzes and its use in forensic science Abstract Volume 6 Issue 5 - 2018 Over the centuries, the history of drug and drug use has undergone significant changes Jefferson Lemes Carvalho in Forensic Sciences, in which Toxicology is used, mainly in the toxicological Laboratory of the Legal Medical Institute Leonídio Ribeiro, analyzes and methods used routinely by civil or criminal experts. Toxicology, federal District, Brazil as a multifunctional science, covers several other related areas, such as Clinical Toxicology, Social Toxicology, Environmental Toxicology and Occupational Correspondence: Jefferson Lemes Carvalho, Laboratory of Toxicology, Toxicology applied to Doping Control, and essential Forensic Toxicology, the Legal Medical Institute Leonídio Ribeiro, federal District, as well as others. This article was elaborated with searches in scientific publications, Brazil, Email bibliographical reviews, scientific journals and Forensic Science books, as well as other sources of scientific knowledge. There are currently many techniques used in Received: October 04, 2018 | Published: November 16, 2018 the routine of Forensic Toxicology laboratories, among which the use of the following are most frequently used: Thin Layer Chromatography - CCD, Immunoassay methods, High Performance Liquid Chromatography - HPLC, Gas Chromatography - GC and Liquid or Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrophotometry - HPLC/ MS. Throughout this article, in a -

As Seen on Forensic Update – NFSTC@FIU 1

As Seen on Forensic Update – NFSTC@FIU 1 As Seen on Forensic Update Saw something cool in the Forensic Update? You can get all the details from each edition via the links below. NFSTC’s online forensic news series is where we share some of the coolest technologies and industry news. November 2019 • Thermo Fisher Rapid DNA Center of Excellence • Where DNA falls short in cracking crimes, scientists can use this new tool • A safer way for police to test drug evidence • A breath test for opioids • Opioids PPE • A fourth amendment framework for voiceprint database searches October 2019 • Department of Justice announces interim policy on emerging method to generate leads for unsolved violent crimes • Pitt researchers create breathalyzer that can detect marijuana • ANSI National Accreditation Board • FIU Digital Forensics Professional Program • NICE Conference • 9th Annual Forensic Science Symposium September 2019 • NFSTC@FIU named Rapid DNA Center of Excellence by Thermo Fisher Scientific • Fentanyl analogue identification toolkit aids forensic toxicology • ISHI student ambassadors • GCC Forensics Conference and Symposium • Forensic Science Week August 2019 • NIST’s new PCR-based DNA profiling standards • Research: Improving the chemiluminescense of luminol • Was that song stolen? Forensic Musicology with Joe Bennett, PhD, of the Berklee College of Music. Listen to the full interview here. As Seen on Forensic Update – NFSTC@FIU 2 July 2019 • How forensic face recognition works • SOCOM seeks smartphone app for fingerprint data • Deep fakes: Researchers