Spaces of the Recent Past: Cinematic Investigations for a Marketplace In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APRES Moi LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL Review in HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY

"APRES MoI LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL REvIEw IN HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY Tahirih V. Lee* INTRODUCTION One of the burning questions stemming from China's promise that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) would enjoy a "high degree of autonomy" is whether the HKSAR's courts would have the authority to review issues of constitutional magnitude and, if so, whether their decisions on these issues would stand free of interference by the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 promulgated in PRC law and international law a guaranty that implied a positive answer to this question: "the judicial system previously practised in Hong Kong shall be maintained except for those changes consequent upon the vesting in the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the power of final adjudication."' The PRC further promised in the Joint Declaration that the "Uludicial power" that was to "be vested in the courts" of the SAR was to be exercised "independently and free from any interference."2 The only limit upon the discretion of judicial decisions mentioned in the Joint Declaration was "the laws of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and [to a lesser extent] precedents in other common law jurisdictions."3 Despite these promises, however, most of the academic and popular discussion about Hong Kong's judiciary in the United States, and much of it in Hong Kong, during the several years leading up to the reversion to Chinese sovereignty, revolved around a fear about its decline after the reversion.4 The * Associate Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law. -

Life and Death of Kowloon Walled City Antonín Brinda

Life and Death of Kowloon Walled City Antonín Brinda The text you are about to read speaks about the island of Hong Kong which is by itself an exceptional place with a very specific history. There is (or maybe better to say was) nevertheless an arguably even more interesting island located within the territory of Hong Kong: Chinese enclave called Kowloon Walled City (KWC). What surrounded this 'island' was not water but „larger territory whose inhabitants are culturally or ethnically distinct“ (Oxford Dictionary's definition of enclave). Though in this case, the situation is somewhat more complicated, as KWC – officially part of China – was at the time surrounded by another piece of land formerly also belonging to China – British Hong Kong. Therefore one might say that a part of China was surrounded by another part of China, but that would be a quite a simplification. Decades of British domination had a significant impact on Hong Kong as well as unexpected juridical implications strongly influenced the nature of KWC. It is then legitimate to talk about KWC and Hong Kong as two entities, quite distinct from both each other and Mainland China, the smaller one strangely inserted into the body of its bigger neighbor. Let us explore together this unique 'island' and its 'waters'. The paper aims to shortly introduce the history of an urbanistic phenomenon of Kowloon Walled City (KWC) which until 1993 had been located in the territory currently known as Hong Kong (Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China). In the four parts of the article, I will look upon (1) the establishment and development of Kowloon City (Sung Dynasty - 1847), (2) the birth of the Walled City within the Kowloon City area (1847-1945), (3) the post-Second World War period during which the City received its reputation and the nickname 'City of Darkness' (1945-1993), and (4) the concurrent afterlife following the City's demolition in 1993 (1993-now). -

Examples of Books on Cultural Development of Hong Kong Personal, Social and Humanities Education, Curriculum Development Institute

Examples of Books on Cultural Development of Hong Kong Personal, Social and Humanities Education, Curriculum Development Institute Examples of Books on Cultural Development of Hong Kong General 1. Bard, S. (1988). Solomon Bard's in Search of the Past: A Guide to the Antiquities of Hong Kong. Hong Kong: the Urban Council. 2. Chung, T. (1991). A Journey into Hong Kong's Archaeological Past. Hong Kong: Regional Council. 3. Lim, P. (2002). Discovering Hong Kong's Cultural Heritage: The New Territories (With 13 Guided Walks). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. 4. Lim, P. (2002). Discovering Hong Kong's Cultural Heritage: Hong Kong and Kowloon (With 19 Guided Walks). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. 5. Lee, O.F. (2008). City between Worlds: My Hong Kong. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. 6. Owen, N. (1999). The Heritage of Hong Kong: Its History, Architecture & Culture. Hong Kong: FormAsia. 7. Ward, B., Law, J. (1993).Chinese Festivals in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Guidebook Company Ltd. 18 Districts Central and Western District 8. Hui, D. (2004). Selected Historic Buildings and Sites in Central District. Hong Kong: Antiquities and Monuments Office of the Leisure and Cultural Services Dept. 9. Leung, P. W. (1999). Heritage of the Central and Western District, Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Central & Western Provisional District Board. Islands District 10. Wong, W. K. (2000). Tai O: Love Stories of the Fishing Village. Hong Kong: Jinyibu Duomeiti Youxian Gongsi. Sham Shui Po District 11. Society for Community Organization. (2008). West Kowloon: Where Life, Heritage and Culture Meet. Hong Kong: Society for Community Organization. -

Gweilo: Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood Ebook

GWEILO: MEMORIES OF A HONG KONG CHILDHOOD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Booth | 384 pages | 06 Sep 2005 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780553816723 | English | London, United Kingdom Gweilo: Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood PDF Book Initially, many Hong Kongers were optimistic about reunification with China. Shelve Daydreams of Angels. Special financing available Select PayPal Credit at checkout to have the option to pay over time. He began working for the 14K, a notorious… More. Some of the food in Hong Kong is truly unforgettable. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. Shelve Punisher: Soviet. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Full of local colour and packed with incident. His father, a pedantic, embittered Admiralty clerk, openly loathed the "natives" and relished his power as a "gweilo", the Cantonese nickname for the white man. By using Tripsavvy, you accept our. A journalist and blogger takes us on a colorful and spicy gastronomic tour through Viet Nam in this entertaining, offbeat travel memoir, with a foreword by Anthony Bourdain. Generous-size, round tables abound to accommodate large groups and families. Summer Namespaces Article Talk. While the city of Victoria used to house the capital, it now rests in a central location of Hong Kong. Located on the second floor of Cosmo Hotel Mongkok, this cinema-inspired eatery is named after the Italian film studio that produced the work of renowned director Federico Fellini. Luxe Lounges When it comes to sipping, grazing, and posing, Hong Kong doesn't miss a beat. More From Reference. Susan Recommends My mother was full of fun, with a quick wit, an abounding sense of humour, an easy ability to make friends from all walks of life and an intense intellectual curiosity. -

The History of Planning for Kowloon City

Manuscript for Planning Perspective The History of Planning for Kowloon City *Lawrence W.C. Lai ** Mark Hansley Chua *Professor Ronald Coase Centre for Property Rights Research, Department of Real Estate & Construction University of Hong Kong Registered Professional Planner, F.R.I.C.S., M.R.A.P.I. [email protected] ** Doctoral candidate Department of Real Estate & Construction University of Hong Kong [email protected] [email protected] 1 Manuscript for Planning Perspective The History of Planning for Kowloon City Lawrence W.C. Lai and Mark H. Chua University of Hong Kong 5 March 2017 Keywords Kowloon City, city of darkness, town plans, history of planning Abstract This short paper identifies from archival and published materials plans for a place called Kowloon City which had an Imperial Chinese military purpose and is now a public park (officially called “Kowloon Walled City Park”) after a long period of dispute over its jurisdiction. These plans were mostly produced by the colonial Hong Kong government who made the first planned attempt to clear the place of Chinese residents for a public garden in the 1930s but this garden could only be built after the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. They testified to the fact that the City has always been planned. Introduction The disclosure of formerly secret and confidential colonial Hong Kong government documents to the public has stimulated research on the mapping and planning of use of a famous place in Hong Kong called “Kowloon City”1 (hereafter referred to as the City), as can be found in the works of Lai et al. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ‘Designs against a common foe’ the Anglo-Qing suppression of piracy in South China Kwan, Nathan Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Abstract of thesis entitled ‘Designs against a Common Foe’: The Anglo-Qing Suppression of Piracy in South China Submitted by C. -

Kowloon Walled City

Land Use Policy 76 (2018) 157–165 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Land Use Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol Quality of life in a “high-rise lawless slum”: A study of the “Kowloon Walled T City” ⁎ Lau Leung Kwok Prudencea, , Lai Wai Chung Lawrenceb, Ho Chi Wing Danielb a Department of Cultural and Creative Arts, The Education University of Hong Kong, Tai Po, Hong Kong b Department of Real Estate & Construction, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Informed by the ‘quality of life’ model with specific reference to Chinese culture, this article uses reliable and Kowloon Walled City publicly available information seldom used in historical or heritage study to identify the designs of flats and Quality of life builders of the “Kowloon Walled City” (hereafter the City) and reliable oral testimonies to refute some myths Builders about the quality of life within it. This settlement has been notoriously misrepresented by some as a city of Housing unit darkness that was razed from the face of the Earth before 1997 to fulfill a pre-war dream of the colonial gov- Life satisfaction ernment. This article confirms the view that this extremely short-lived concrete jungle, mystified as a horrifying, disorderly-built, and unplanned territory, was a product of un-organised small builders that had been hitherto unreported. The layout and designs of the housing units were different from that prescribed by the Buildings Ordinance, but were, in fact, developed within a consciously planned boundary that was a result of international politics. Although the City’s overall built environment was poor due to a lack of natural light penetration, the designs of its individual flats were comparable, if not better than, typical units in contemporary public rental housing blocks, many of which had to be demolished less than 20 years after their construction due to structural defects. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) The Spatial Production of Films Illustrated by the Case of Hong Kong Kowloon Walled City Ge Zheng The College of Literature and Journalism Sichuan University Chengdu, China Abstract—Due to the unique political background, complex was knocked down by the Hong Kong government in 1993 construction, the living conditions of the chaos, the Hong Kong and the Kowloon Walled City Park had been built there. Kowloon Walled city has become the focus of public concern, especially providing a rich source for artists. It is not only a II. THE PRODUCTION OF SYMBOL SPACE IN FILMS space entity, but also a cultural symbol, a kind of representational space. This article applies the theory of Space One of the best frames in the movie Chasing the Dragon to discuss the relationship of the different spaces which is is the pursuit in the Walled City. Inspector Lei Luo meant illustrated by the case of the Kowloon Walled city in movies. It nothing threatened to this place, and the airplane that seemed shows the cultural symbolic meaning behind so that a glimpse to be easily touched was also like its environment before. can be put into the social production of spatial operation mode. Most Hong Kong movies on the background of Kowloon Walled City are themed by crime and gangsters showing the Keywords—Kowloon Walled city; spaces in movie; theory of chaotic and violent colonial life, such as Brothers from the space; cultural symbol Walled City in 1982, Long Arm of the Law Part 1 in 1984, To Be Number One in 1991, Crime Story in 1993, The H.K. -

Performing Arts 54-62

Contents Pages Foreword 1-2 Performance Pledges 3 Vision, Mission and Values 4-5 Feedback Channels 6 Leisure Services 7-51 Recreational and Sports Facilities 8-18 Recreational and Sports Programmes 19-24 Sports Subvention Scheme 25-26 Beijing 2008 Olympic Games 27-30 Hong Kong 2009 East Asian Games 31-33 The 2nd Hong Kong Games 34-35 Sports Exchange and Co-operation Programmes 36 Horticulture and Amenities 37-41 Green Promotion 42-44 Licensing 45 Major Recreational and Sports Events 46-51 Cultural Services 52-125 Performing Arts 54-62 Cultural Presentations 63-66 Festivals 67-69 Arts Education and Audience-Building Programmes 70-73 Carnivals and Entertainment Programmes 74-75 Subvention to Hong Kong Arts Festival 76 Conferences and Cultural Exchanges 77-79 Film and Video Programmes 80-81 Music Office 82 Indoor Stadia 83-84 Urban Ticketing System (URBTIX) 85 Public Libraries 86-93 Museums 94-108 Central Conservation Section 109-110 Antiquities and Monuments Office 111-112 Expert Advisers on Cultural Services 113 Major Cultural Events 114-125 Administration 126-152 Financial Management 126-127 Public Feedback 128 Outsourcing 129-130 Human Resources 131-139 Environmental Efforts 140-142 Facilities and Projects 143-145 Information Technology 146-150 Public Relations and Publicity 151-152 Appendices 153-174 Foreword 2008-09 was another busy year for the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD). A distinct highlight of the year was the Beijing 2008 Olympic and Paralympic Games, the first Olympic and Paralympic Games ever held on Chinese soil. Hong Kong had the great honour of co-hosting the Equestrian Events. -

Hong Kong: City in Transition

Hong Kong: City In Transition November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide Hong Kong: City In Transition 1 Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Background Information ............................................................................................................. 4 Location and Geographical Information ..................................................................................... 4 A Colony is Created (1842-1930) ............................................................................................... 4 Pre-War Year and Occupation (1930-1945) ............................................................................... 5 Report on Key Issues .................................................................................................................... 6 Issue #1: Relations with Mainland China and Chinese People ................................................... 6 Issue #2: Development of Adequate Infrastructure..................................................................... 7 Issue #3: The Government's Responsibility for Hong Kong? ..................................................... 8 Committee Mechanics .................................................................................................................. 9 Debate......................................................................................................................................... -

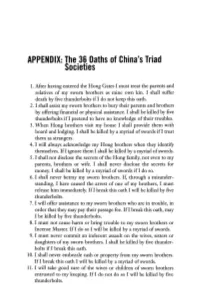

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master. -

The Second Life of Kowloon Walled City

CMC0010.1177/1741659017703681Crime, Media, CultureFraser and Li 703681research-articleView2017 metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten Article Crime Media Culture 2017, Vol. 13(2) 217 –234 The second life of Kowloon Walled © The Author(s) 2017 City: Crime, media and cultural https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017703681Reprints and permissions: memory sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1741659017703681 journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc Alistair Fraser University of Glasgow, UK Eva Cheuk-Yin Li King’s College London, UK Abstract Kowloon Walled City (hereafter KWC or Walled City), Hong Kong has been described as ‘one of history’s great anomalies’. The territory remained under Chinese rule throughout the period of British colonialism, with neither jurisdiction wishing to take active responsibility for its administration. In the postwar period, the area became notorious for vice, drugs and unsanitary living conditions, yet also attracted the attention of artists, photographers and writers, who viewed it as an instance of anarchic urbanism. Despite its demolition in 1993, KWC has continued to capture the imaginations of successive generations across Asia. Drawing on data from an oral and visual history project on the enclave, alongside images, interviews and observations regarding the ‘second life’ of KWC, this article will trace the unique flow of meanings and reimaginings that KWC has inspired. The article will locate the peculiar collisions of crime and consumerism prompted by KWC within the broader contexts in which they are embedded, seeking out a new interdisciplinary perspective that attends to the internecine spaces of crime, media and culture in contemporary Asian societies.