Oye Como Va!: Hybridity and Identity in Latino Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-011534Lbr

Legacy Business Registry Executive Summary HEARING DATE: JANUARY 6, 2021 Filing Date: December 9, 2020 Case No.: 2020-011534LBR Business Name: 24th Street Dental Business Address: 2720 24th St Zoning: NCT - 24th-Mission Neighborhood Commercial Transit Calle 24 SUD 65-X Block/Lot: 4211/016 Applicant: Dr. Bernardo D. Gonzalez III 2720 24th Street, San Francisco, CA 94110 Nominated By: Supervisor Hillary Ronen Located In: District 9 Staff Contact: Kalyani Agnihotri – (628)652-7454 [email protected] Recommendation: Adopt a Resolution to Recommend Approval Business Description 24th Street Dental is a dental practice owned by Dr. Bernardo D. Gonzalez III, located at 2720 24th Street in the Mission District. The address’ history dates back to before the dental practice was established in 1985 when it was the location of the shoe store owned by Dr. Gonzalez’s father. Dr. Gonzalez, a fixture of the city’s local music scene, came to be known as “Dr. Rock,” when he served as manager of the pioneering Latin rock group Malo and organized the annual benefit “Voices of Latin Rock” for 10 years. While concurrently running his dental practice, Dr. Rock has continually been involved in significant Mission cultural activities. In 1981, Dr. Rock helped produce the 24th Street Fair for the 24th Street Merchants Association, and subsequently became their president. After his successes with the 24th St. Merchants Association, Dr. Rock created the Mission Economic Cultural Association, or MECA along with Roberto Hernandez, which produced the 24th Street Fair, Cinco de Mayo, and Legacy Business Registry 2020-011534 LBR January 6, 2021 Hearing 24th Street Dental Carnaval. -

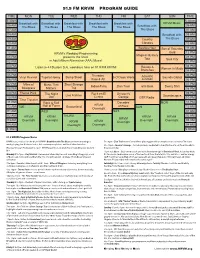

Vertical Program Guide CW 9

91.9 FM KRVM PROGRAM GUIDE TIME MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN TIME 5:30am 5:30am Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with KRVM Music 06 AM 06 AM The Blues The Blues The Blues The Blues The Blues Breakfast with 07 AM The Blues 07 AM 08 AM Breakfast with 08 AM 09 AM Country The Blues 09 AM 10 AM Classics 10 AM 11 AM Beatles Hour Son of Saturday 11 AM 12 PM KRVM’s Weekday Programming Gold 12 PM Magical Mystery 01 PM presents the finest 01 PM Tour Soul City 02 PM in Adult Album Alternative (AAA) Music! 02 PM 03 PM 03 PM Listen to 4J Student DJs, weekdays here on 91.9 FM KRVM! Routes & Women in Music 04 PM Branches 04 PM 05 PM Thursday 05 PM Vinyl Revival Tupelo Honey Bump Skool 5 O’Clock World Acoustic Sounds Global 06 PM Free 4 All Junction 06 PM 07 PM Miles of Music That Short Strange 07 PM Indian Time Zion Train 60s Beat Swing Shift 08 PM Bluegrass Matters Trip 08 PM 09 PM Theme Park The Night Rock en El Greaser’s 09 PM Live Archive Soundscapes 10 PM Owl Centro Garage GTR Radio 10 PM Time Traveler 11 PM Rock & Roll Decades MON 11 PM KRVM 12 AM TUE Hall of Fame Grooveland of Rock SUN 12 AM Overnight 01 AM WED SAT 01 AM 02 AM KRVM KRVM THURS FRI KRVM KRVM 02 AM KRVM 03 AM Overnight Overnight Overnight Overnight 03 AM KRVM KRVM Overnight 04 AM Overnight Overnight 04 AM 5:30am 5:30am 91.9 KRVM Program Notes KRVM is your station for the blues! KRVM's Breakfast with The Blues airs seven mornings a 7 to 9pm - Zion Train hosts Corey & Pete play reggae with an emphasis on conscious 70s roots. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Student Study Outline

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Student Study Outline I. The “Me” Decade a. Tom Wolfe’s label b. Music industry reached new heights of consolidation II. Singer-Songwriters: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor a. Carole King (b. 1942): career illustrates the central prominence of singer- songwriters in this period i. Tapestry (1971): album whose success made King a major recording star b. Joni Mitchell (b. 1943): began career as songwriter, started recording on her own in 1968 i. Blue (1971): best-known album; cycle of songs about complexity of love c. James Taylor (b. 1948): perhaps the most successful long-running career of the 1970s era singer-songwriters i. Sweet Baby James (1970): hugely successful album with many hit singles, including number three hit “Fire and Rain.” III. Country Music and the Pop Mainstream a. Country-pop crossover accomplished by a new generation of musicians: i. Glen Campbell (b. 1936) ii. Charlie Rich (b. 1932) iii. Olivia Newton-John (b. 1948) iv. Dolly Parton (b. 1946) v. John Denver (1943‒1997) IV. Box 11.1: Hardcore Country: Merle Haggard and the Bakersfield Sound a. Merle Haggard (b. 1937) V. Country Rock: The Eagles a. The Eagles: influential band who epitomized the culture of Southern California i. Ambitious saga “Hotel California” cashed in on this association VI. Rock Comes of Age a. Pop rock and soft rock i. Elton John (b.1947): continued trend of long-running “British occupation” of the American pop charts 1. “Crocodile Rock” and nostalgia b. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories. -

RADIO ROCKWAY Odalys Cordero

RADIO ROCKWAY Odalys Cordero Preface It is with great pleasure that I share a Johnny Mercer inspired unit entitled: “Radio Rockway.” This unit utilizes interdisciplinary instruction within a musical setting. The target student audience throughout the curriculum is the 5th grade student population but can easily be adapted to middle and high school level students. The unit is typically completed in approximately nine weeks if music class is taught one hour a week. This unit is designed to educate students on the history and elements of Latin Jazz while simultaneously establishing a creative environment for student to create their own lyrics. On a personal note, I enjoyed witnessing the musical growth in each 5th grade class as they used the framework of pre-existing Latin Jazz songs and lyrically “made it their own,” so to speak. This was a great opportunity for Spanish speakers at an ESOL Level of 1 & 2 level to express themselves more freely throughout the progression of the unit. Overall Organization of Unit UNIT COVER PAGE Unit Title: “Radio Rockway” Grade Level: 5th Grade Subject/Topic Area(s): Studying a selected musical genre typically played on the radio: Latin Jazz. Designed By: Odalys Cordero , Florida International University Unit Duration: 9 Weeks Brief Summary of Unit (Including curricular context and unit goals): Three classes of 5th grade students will learn about the genre of Latin Jazz. This unit will be based on experiencing and creating lyrics to this particular genre. Each class will take on the role of a radio station with the assigned genre. Through these radio stations, students will perform their composition lyrics. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

MUSIC, Dvds, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS

MUSIC, DVDs, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS ® and “Hi! I’m Christy Lane, creator of Dare to Dance owner of Christy Lane Enterprises. How can we help you? As you browse through this catalog, you will notice we expanded our line of products and services. When our company was established 20 years ago our philosophy was simple. To educate children that dance can benefit them physically, mentally, That's me on my first video shoot. socially, and emotionally. We did this by producing quality educational products for the physical Catalog Listings: education teachers and dance studio instructors. LINE DANCING Our customer base has expanded tremendously over PARTY DANCING the years and so has the popularity of dance. Now, DECADE DANCING moms, dads, single adults, seniors, and kids who HIP HOP have never danced before are dancing! So join the PARTNER/BALLROOM fun!” LATIN DANCING SQUARE DANCING AMERICA SPORTS & NOVELTY MULTICULTURAL FOLK Christy Lane is one of America’s most well-known and respected dance instructors. Her DANCING extensive dance training has led her to become an acknowledged dance educator, producer, choreographer, and writer. Her work has been recognized by U.S. News and World Report, AFRICAN-CARIBBEAN American Fitness, USA Today and Shape Magazine. Her credits include Disney, Pepsi and DANCING Capezio to name a few. A former private dance studio owner, she tours nationally and her PHYSICAL FITNESS conventions and workshops have delighted thousands of all ages. MUSIC EDITING JAZZ DANCING TAP DANCING DANCE CONVENTIONS HOLIDAY DANCE SHIRTS DANCE FLOORS SOUND SYSTEMS & MICROPHONES TEACHER WORKSHOPS “Christy Lane has the magic to motivate the non-dancer and insight to move DANCE SCHOOL ASSEMBLIES accomplished dancers to the next level.”-Bud Turner, P.E. -

Geschiedenis Van De Rockmuziek Gratis Epub, Ebook

GESCHIEDENIS VAN DE ROCKMUZIEK GRATIS Auteur: David Roberts Aantal pagina's: 576 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2013-08-01 Uitgever: Librero Nederland B.V. EAN: 9789089983251 Taal: nl Link: Download hier De geschiedenis van de rockmuziek Zo kun je meteen zien welke muzikanten wanneer meespeelden en op welke instrumenten, bij welke platenlabels de band zat, wanneer de albums uitkwamen en wie daarop meespeelden. Bovendien zie je de verkoopcijfers van de succesvolste albums van topbands. Van meer dan vijftig van de belangrijkste bands is de beschrijving aangevuld met een dubbele fotopagina, die een schitterend overzicht geeft van de veranderingen in hun uiterlijk, gekoppeld aan hun beste albums en historische hoogtepunten. Achter in het boek staat een uitgebreid artiestenregister. Hierin staan alle beschreven muzikanten vermeld, zodat je de rockcarrière van de afzonderlijke bandleden kunt volgen van de ene band naar de andere, en weer terug. Boeiend, uitgebreid en boordevol informatie: Geschiedenis van de rockmuziek is hét naslagwerk voor iedereen die van rock houdt. Bekijk ook eens deze boeken. Vinyl Mike Evans. Jimi Hendrix Gillian G. Na Curtis' dood bracht de band nog Closer uit, het tweede en laatste album. De overige bandleden creëerden een nieuwe band: New Order. Een nieuwe stroming bands in de jaren 80 werd onder de noemer " alternatieve rock " geschaard, die gebruikt werd om punkrockgeïnspireerde bands te beschrijven die niet in de mainstreammuziek pasten. Een van de eerste albums die tot de alternatieve rock werden gerekend, was Murmur , het debuut van de Amerikaanse band R. Deze band werd eind jaren 80 een gevestigde naam, met albums als Out of Time en Automatic for the People. -

International Agenda Vol

with the A student from the Univ. of New England is engrossed by her up‐close learning in the small island nation of Dominica. Inside, Professor Thomas Klak shares lessons from the experience (p. 14). See pages 10-35 for coverage of Schoolcraft College’s year-long Focus Caribbean project. p. 3 Schoolcraft College International Institute International Agenda Vol. 13, No. 2 Fall 2014 International Institute (SCII) Published once per semester by Schoolcraft College the International Institute (SCII) 18600 Haggerty Road Livonia, MI 48152-2696 Editorial Committee: http://www.schoolcraft.edu/department-areas/ Chair: Randy K. Schwartz (Mathematics Dept.) international-institute/ Sumita Chaudhery (English Dept.) Helen Ditouras (English Dept.) The mission of the Schoolcraft College International Kim Dyer (History Dept.) Institute is to coordinate cross-cultural learning Mark Huston (Philosophy Dept.) opportunities for students, faculty, staff, and the Josselyn Moore (Anthropology/ Sociology Depts.) community. The Institute strives to enhance the Suzanne Stichler (Spanish Dept.) international content of coursework, programs, and other Yovana P. Veerasamy (French Dept.) College activities so participants better appreciate both the diversities and commonalities among world cultures, and e-mail: [email protected] better understand the global forces shaping people’s lives. voice: 734-462-4400 ext. 5290 fax: 734-462-4531 SCII Administrative Director: Cheryl Hawkins (Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences) Material contained in International Agenda