War in Cinema and Electronic Gaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between Politics and Popular Culture at the End of Wars

Conflict, Culture, Closure: The interaction between politics and popular culture at the end of wars Cahir O’Doherty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University August 2019 ii Abstract In this thesis I engage with the topic of how popular culture and politics interact at the end of conflict. Using contemporary Hollywood action cinema from 2000 to 2014 and political speeches from the Bush and Obama administrations, I pose the question of how do these seemingly disparate fields forge intense connections between and through each other in order to create conditions of success in the War on Terror. I utilise the end of wars assemblage to argue that through intense and affective encounters between cinema screen and audiences, certain conditions of success emerge from the assemblage. These conditions include American exceptionalism and the values it exemplifies; the use of technology in warfare as co-productive of moral subjectivities; the necessity of sacrifice; and the centrality of the urban landscape and built environment. I then proceed to assess the resilience of the end of wars assemblage and its conditions of success by engaging with cinematic and political artefacts that have the potential to destabilise the assemblage through genre inversion and alternative temporalities. Ultimately, I argue that the assemblage and its conditions of success are strongly resilient to change and critique. The conditions of success that emerge from the assemblage through intense affective encounters can then be politically deployed make a claim that a war has ended or will end. Because audiences have been pre-primed to connect these conditions to victory, such a claim has greater persuasive power. -

H1 FY12 Earnings Presentation

H1 FY12 Earnings Presentation November 08, 2011 Yves Guillemot, President and Chief Executive Officer Alain Martinez, Chief Financial Officer Jean-Benoît Roquette, Head of Investor Relations Disclaimer This statement may contain estimated financial data, information on future projects and transactions and future business results/performance. Such forward-looking data are provided for estimation purposes only. They are subject to market risks and uncertainties and may vary significantly compared with the actual results that will be published. The estimated financial data have been presented to the Board of Directors and have not been audited by the Statutory Auditors. (Additional information is specified in the most recent Ubisoft Registration Document filed on June 28, 2011 with the French Financial Markets Authority (l’Autorité des marchés financiers)). 2 Summary H1 : Better than expected topline and operating income performance with strong growth margin improvement H1 : Across the board performance : Online − Casual − High Definition H2 : High potential H2 line-up for casual and passionate players, targeting Thriving HD, online platforms and casual segments H2 : Quality improves significantly Online : Continue to strenghten our offering and expertise FY12 : Confirming guidance for FY12 FY13 : Improvement in operating income and back to positive cash-flows 3 Agenda H1 FY12 performance H2 FY12 line-up and guidance 4 H1 FY12 : Sales Q2 Sales higher than guidance (146 M€ vs 99 M€) Across the board performance : Online − Casual − HD Benefits -

KILLER GAMES for 2010 Lost Planet 2 Kicks Off the Hottest Year in Gaming March 2010

HALO: REACH • DEAD SPACE 2 • TRUE CRIME OFFICIAL XBOX MAGAZINE OFFICIAL XBOX GIANT MONSTERS! 4-PLAYER ACTION! HELL YEAH! GET READY! LOST PLANETLOST 2 100KILLER GAMES FOR 2010 Lost Planet 2 kicks off the hottest year in gaming March 2010 March FINALLY! BIOSHOCK 2 Reviewed here fi rst! MARCH 2010 • ISSUE 107 MEET THE TEAM Letter From the Editor There’s no place like home Issue 107 • March 2010 EDITORIAL EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Francesca Reyes 2010. It’s barely under way as I type this, but it MANAGING EDITOR Corey Cohen already feels like it’s going to be one of those mega- SENIOR EDITOR Ryan McCaffrey FEATURES EDITOR Kevin W. Smith years in gaming — one that all of us will be talking EDITORIAL SUPER-INTERN Taylor Cocke about well into the future in hushed, reverent tones. EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS Mike Channell, Alex Clark, Mitch Dyer, Why? Because it’s one of the big-time bullet-points Andrew Hayward, Cameron Lewis, Chris Morris, in the Great Big Videogame Cycle™ when the stars Chuck Osborn, Matthew Pellett, Will Porter, Ben Talbot, Meghan Watt align and we get the much-anticipated “Part IIs” (or “These dark whatever chapter each series is on at this point) that ART revamp, relaunch, or revisit universes we still hold CONTRIBUTING ART DIRECTOR/PHOTOGRAPHER Juliann Brown little places CONTRIBUTING GRAPHIC DESIGNER/ILLUSTRATOR dear years after the originals. Just think: Mass of fi ction and Christina Empedocles Effect 2, BioShock 2, Lost Planet 2, Dead Rising 2, CONTRIBUTING COVER DESIGNER Monique Convertito Fable III, a new Fallout…the list just stretches far into wonder are BUSINESS the furthest reaches of 2010 without end. -

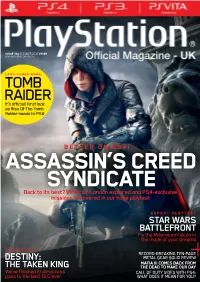

Official Playstation Magazine! Get Your Copy of the Game We Called A, “Return to Form for the Legendary Spookster,” in OPM #108 When You Subscribe

ISSUE 114 OCTOBER 2015 £5.99 gamesradar.com/opm LARA COMES HOME TOMB RAIDER It’s official! First look as Rise Of The Tomb Raider heads to PS4 ASSASSIN’SBETTER ON PS4! CREED SYNDICATE Back to its best? Victorian London explored and PS4-exclusive missions uncovered in our huge playtest EXPERT PLAYTEST STAR WARS BATTLEFRONT Fly the Millennium Falcon in the mode of your dreams COMPLETED! RECORD-BREAKING TEN-PAGE METAL GEAR SOLID REVIEW DESTINY: MAFIA III COMES BACK FROM THE TAKEN KING THE DEAD TO MAKE OUR DAY We’ve finished it! All-access CALL OF DUTY SIDES WITH PS4: pass to the best DLC ever WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR YOU? ISSUE 114 / OCT 2015 Future Publishing Ltd, Quay House, The Ambury, Welcome Bath BA1 1UA, United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1225 442244 Fax: +44 (0) 1225 732275 here’s just no stopping the PS4 train. Email [email protected] Twitter @OPM_UK Web www.gamesradar.com/opm With Sony’s super-machine on track to EDITORIAL Editor Matthew Pellett @Pelloki eventually overtake PS2 as the best- Managing Art Editor Milford Coppock @milfcoppock T Production Editor Dom Reseigh-Lincoln @furianreseigh selling console ever, developers keep News Editor Dave Meikleham flocking to Team PlayStation. This month we CONTRIBUTORS Words Alice Bell, Jenny Baker, Ben Borthwick, Matthew Clapham, Ian Dransfield, Matthew Elliott, Edwin Evans-Thirlwell, go behind the scenes of five of the best Matthew Gilman, Ben Griffin, Dave Houghton, Phil Iwaniuk, Jordan Farley, Louis Pattison, Paul Randall, Jem Roberts, Sam games due out this year to show you why Roberts, Tom Sykes, Justin Towell, Ben Wilson, Iain Wilson Design Andrew Leung, Rob Speed the biggest blockbusters of the gaming ADVERTISING world are set to be better on PS4. -

Bikini Bottom Geek Meet Spongebob Squarepants Writer Derek Iversen

Student Life Magazine The University of Advancing Technology Issue 4 WINTER/SPRING 2009 34 BIKINI BOTTOM GEEK MEET SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS WRITER DEREK IVERSEN 18 SPRUCE YOUR EWARDROBE SMART CLOTHES Are THE APEX OF EMBEDDED SYSTEMS 10 THE LITTLE BIG BANG SECRETS OF THE UNIVERSE PART 2 $6.95 WINTER/SPRING T.O.C. • • • 10 THEHE LITTLELITTLE BIGBIG BANGBANG Secrets of the Universe, Part 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS GEEK 411 ISSUE 4 WINTER/SPRING 2009 ABOUT UAT 8 UAT IN THE NEWS 30 UAT BOOKSTORE 38 MEET THE FACULTY 45 MEET THE STAFF INSIDE THE TECH WORLD FEATURE 20 DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP STORIES 31 GEEK TEST 40 MAKING IT, GAMER STYLE 39 GADGETS & GIZMOS 18 SPRUCE UP YOUR EWARDROBE 36 WHAT’S HOT, WHAT’S NOT FIND OUT WHAT’S HOT IN EMERGING SMART CLOTHES TECHNOLOGY 4 EVENTS ESSENTIAL STUDENT INFO 16 A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A DORM STUDENT 44 BACKGROUND ON UAT 33 REGISTRATION INFO 43 WHERE TO FIND WHAT YOU NEED 50 UAT STUDENT CLUBS & GROUPS 9 TRAVEL SCHEDULE 25 EMOTIONAL ROBOTS PEOPLE THE ROBOTIC SPIDER THAT REMEMBERS YOUR FACE 5 ZERO BARRIER 26 RAY KURZWEIL 32 STUDENT BLOGS 14 FACULTY PROFILE {RYAN CLARKE} 12 SHRED NEBULA 29 MEET NEW FRESHMEN 34 BIKINI BOTTOM GEEK 15 UAT COMMUNITY SERVICE MEET SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 22 UAT STUDENTS SET NEAR SPACE RECORD WRITER DEREK IVERSEN 27 ALUMNI BAND TOGETHER TO LAUNCH NEW COMPANY © CONTENTS COPYRIGHT BY FABCOM 2008 Fly-In The UAT Fly-in G33K Program gives you the opportunity to tour The Game Developers Conference GDC G33k our unique technology-infused defines the future of the multi- campus, sit in on classes, 2009 billion dollar game industry and Program eat at the campus cafe, meet www.gdconf.com shapes the next generation of www.uat.edu/flyingeek with Admissions and Financial San Francisco, CA entertainment. -

Drpjournal 1Pm S1 2010.Pdf (PDF

!"#"$%&'()&$)*+, -."/+*,"$0'12'304.+0 5556%*$,6),046+4)6%)74"#"$%&8)&$)*+, JOURNAL OF DIGITAL RESEARCH & PUBLISHING Vol 3, Issue 1 , Semester 1, 2010 Tuesday 1pm class Journal of Digital Research and Publishing Vol 3, No 1. June 2010 This edition was created by students in ARIN6912 Digital Research and Publishing, June 2010. Digital Cultures University of Sydney http://www.arts.usyd.edu.au/digital_cultures/ Lecturer: Chris Chesher Contents Refolding the fold: the complete representation of actuality in digital culture 5 Sonia Therese Chan Mind over media? A philosophical view on usergenerated media and social identity 14 Romina Cavagnola Outsiders looking in: How everyday bloggers are gaining access to the elite fashion world 25 Tiana Stefanic New media revolution: personal ads expand to the Internet 33 David James Misner !"#$"%&'()#$*+$",-&./"$0%1&23"&456$7"&3"8&$8%"6$69& :; Nicola Santilli The practicality of magazine websites 48 Emma Turner A Cultural Historical Approach to Virtual Networking 58 Kate Fagan How social media is changing public relation practices 67 Katharina Otulak The 3D evolution after AVATAR: Welcome to 3D at homes 75 Jaeun Yun The interaction between technology, people and society — In the case of Happy Farm 82 Chen Chen 8 Technical solutions to business challenges: the Content Management System of today 90 Bujuanes Livermore Hidden Consumerism: ‘Advergames’ and preschool children. Parents give the thumbs up? 99 Kathryn Lewis Google’s library of Alexandria: The allure and dangers of online texts 107 Leila Chacko -

![Download Resident Evil 5 Pc Full Version Resident Evil 5: Gold Edition for PC [2.9 GB] Highly Compressed Repack](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8673/download-resident-evil-5-pc-full-version-resident-evil-5-gold-edition-for-pc-2-9-gb-highly-compressed-repack-4678673.webp)

Download Resident Evil 5 Pc Full Version Resident Evil 5: Gold Edition for PC [2.9 GB] Highly Compressed Repack

download resident evil 5 pc full version Resident Evil 5: Gold Edition for PC [2.9 GB] Highly Compressed Repack. • Features new modernized action game control variations, as well as the return of the traditional control schemes. • Extras including all of the original content, two new episodes, four new costumes, an updated Mercenaries Mode . • Playable 2 characters in the standard campaigns, including new character Sheva Alomar, an African BSAA agent . • Cooperatively gameplay . Chris and Sheva must work together to survive challenges and fight hordes of enemies. • I nventory management is done in real time; items can even be assigned, to the directional pad for instant access. Resident Evil 5 Free Download. Resident Evil 5 Free Download game setup in direct link. Also Resident Evil 5 Free is an action adventure and third person shooter video game. Resident Evil 5 Overview. Player will also experience some horror elements in this game. Resident Evil 5 is published by capcom. You might have played other games of Resident Evil series. But this game is something special. Graphic and sound effects are improved. Resident Evil 5 is a 6 th game of Resident Evil game series. This game is based on Chris Redfield. and Sheva Alomar’s investigation. They are investigating a terrorist threat in Kijuju. Kijuju is a fictional area in Africa. You will play Resident Evil 5 from shoulder perspective. Environment of this game plays has important role. Life of player is in danger. You will not see Zombies In this game. Because they are replaced by a new type of enemy called Majini. -

Ubisoft® Reports Third-Quarter 2008-09 Sales

Ubisoft ® reports third-quarter 2008-09 sales Third-quarter sales up 13% to ⁄508 million. Update on the games release schedule. Full-year 2008-09 targets adjusted. Initial targets for 2009-10. Paris, January 22, 2009 œ Today, Ubisoft reported its sales for the third fiscal quarter ended December 31, 2008. Sales Sales for the third quarter of 2008-09 came to ⁄508 million, up 12.9%, or 17.0% at constant exchange rates, compared with the ⁄450 million recorded for the same period of 2007-08. For the first nine months of fiscal 2008-09 sales totaled ⁄852 million versus ⁄711 million in the corresponding prior-year period, representing an increase of 19.8%, or 24.8% at constant exchange rates. Third-quarter sales came in slightly higher than the guidance of approximately ⁄500 million issued when Ubisoft released its sales figures for the second quarter of 2008-09. This performance was primarily attributable to: Þ The diversity and quality of Ubisoft‘s games line-up for the holiday period, with a targeted offering for each type of consumer. Þ A solid showing from franchise titles launched during the quarter, particularly Far Cry ® 2 and Rayman Raving Rabbids ® TV Party which generated sell-in sales of 2.9 million and 1.5 million units respectively and offset the impact of a slower take-off for Prince of Persia ® (2.2 million units). Þ The creation of a new multi-million units selling franchise œ Shaun White Snowboarding œ which was the quarter‘s number two sports game in the United States and recorded 2.3 million units sell-in worldwide. -

Heroism, Gaming, and the Rhetoric of Immortality

Heroism, Gaming, and the Rhetoric of Immortality by Jason Hawreliak A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the Thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Jason Hawreliak 2013 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines rhetorics of heroism and immortality as they are negotiated through a variety of (new) media contexts. The dissertation demonstrates that media technologies in general, and videogames in particular, serve an existential or “death denying” function, which insulates individuals from the terror of mortality. The dissertation also discusses the hero as a rhetorical trope, and suggests that its relationship with immortality makes it a particularly powerful persuasive device. Chapter one provides a historical overview of the hero figure and its relationship with immortality, particularly within the context of ancient Greece. Chapter two examines the material means by which media technologies serve a death denying function, via “symbolic immortality” (inscription), and the McLuhanian concept of extension. Chapter three examines the prevalence of the hero and villain figures in propaganda, with particular attention paid to the use of visual propaganda in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Chapter four situates the videogame as an inherently heroic, death denying medium; videogames can extend the player’s sense of self, provide quantifiable victory criteria, and allow players to participate in “heroic” events. -

Ubisoft® Publie Son Chiffre D'affaires Annuel 2008-09

Ubisoft® publie son chiffre d'affaires annuel 2008-09 Chiffre d'affaires annuel : 1 058 M€, en hausse de 14%. Performance financière attendue pour l'exercice fiscal 2008-09 : 1 − Résultat opérationnel courant à environ 12% du chiffre d'affaires. − Situation financière nette attendue à environ 155 M€. Objectifs 2009-10 confirmés. Paris, le 29 avril 2009 – Ubisoft publie son chiffre d’affaires du quatrième trimestre fiscal, clos le 31 mars 2009. Chiffre d'affaires Le chiffre d'affaires du quatrième trimestre s’élève à 206 M€, en baisse de 5,1% (-2,3% à taux de change constants) par rapport aux 217 M€ réalisés au quatrième trimestre 2007-08. Le chiffre d'affaires annuel s'élève à 1 058 M€, en hausse de 14,0% (+18,4% à taux de change constants) par rapport aux 928 M€ réalisés sur l'exercice 2007-08. Le chiffre d'affaires du quatrième trimestre 2008-09 est en ligne avec l'objectif compris entre 190 M€ et 210 M€ communiqué lors de la publication du chiffre d'affaires du troisième trimestre 2008-09. Ce résultat s'explique principalement par : − La poursuite de la très bonne performance des titres sur Wii™, dont Rayman Raving Rabbids® TV Party, Shaun White Snowboarding: Road Trip et le lancement réussi du jeu My Fitness Coach™. − Les ventes de TOM CLANCY’S H.A.W.X™ qui ont atteint l'objectif de 1 million d'unités en sell-in. − Les franchises Petz® et Imagine® qui ont chacune vendu plus d'un million d'unités en sell-in sur le trimestre. -

Ubisoft® Reports Its Final Sales Figures for Third-Quarter 2011-12

Ubisoft® reports its final sales figures for third-quarter 2011-12 . Final sales for third-quarter 2011-12: €652 million . Full-year targets confirmed Paris, February 15, 2012 – Today, Ubisoft® released its final sales figures for the fiscal quarter ended December 31, 2011. Sales Sales for the third quarter of 2011-12 came to €652 million, up 8.8% (or 11.0% at constant exchange rates) compared with the €600 million recorded for the same period of 2010-11. For the first nine months of fiscal 2011-12, sales totaled €900 million versus €861 million in the corresponding prior-year period, representing an increase of 4.5%, or 9.2% at constant exchange rates. The Group’s final sales for third-quarter 2011-12 are in line with the estimate of around €650 million issued on January 10, 2012 and significantly higher than the guidance of between €580 million and €620 million announced when Ubisoft reported its results for the first half of fiscal 2011-12. This third-quarter performance reflects the following: − A near-30% increase in sales of dance titles, with over 13 million sell-in units, which propelled Ubisoft’s worldwide market share in this high-growth segment to nearly 70%1 in calendar 2011. Just Dance® – Ubisoft’s flagship casual franchise – was once again a star performer, continuing to attract increasing numbers of Wii™ players in addition to launching successfully on Kinect™ and seeing its popularity grow in Continental Europe and Asia. In December 2011, Just Dance 3 was the industry best-sku seller in the United States and in EMEA. -

Playstation Official Magazine

ISSUE 123 JUNE 2016 £5.99 gamesradar.com/opm WORLD EXCLUSIVE HANDS-ON! UNCHARTED 4 MIRROR’S REVIEWED! EDGE Has Nathan Drake Massive Catalyst struck gold again? playtest, because you gotta have Faith… All-slime classic gets reinvented on PS4 EXTENDED PLAY! MAFIA III: It’s GTA IN NEW ORLEANS! TITANFALL 2 BREAKS COVER AT LAST FINAL FANTASY XV KANE AND ABLE: EURO 2016 PREDICTED New screens, new secrets, new movie ISSUE 123 / JUNE 2016 Welcome Future Publishing Ltd, Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA, United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1225 442244 Fax: +44 (0) 1225 732275 es, you are staring at the ghost of Email [email protected] Twitter @OPM_UK Web www.gamesradar.com/opm OPM past. Yes, my doughy frame does EDITORIAL bear an uncanny resemblance to the Acting editor Ben Wilson @BenjiWilson Y Managing art editor Milford Coppock @milfcoppock Production editor Andrew Westbrook @andy_westbrook 1984 manifestation of Gozer. Don’t, however, Staff writer Jen Simpkins @itsJenSim Staff writer Ben Tyrer @bentyrer go calling 555-2368. I’m merely filling in CONTRIBUTORS while editor Matt takes a spring break, Words Jenny Baker, Ben Borthwick, Matthew Clapham, Edwin Evans-Thirlwell, Matt Elliott, Jordan Farley, David Houghton, Leon Hurley, Daniella Lucas, Ben Maxwell, and in doing so helping the team source Dave Meikleham, James Nouch, Louis Pattison, Matthew Pellett, Rhiannon Rees, Sam Roberts, Matt Sakuraoka-Gilman, spook-tacular exclusives such as the first Chris Schilling, Tom Sykes, Robin Valentine, Iain Wilson Design Rob Speed hands-on with Ghostbusters on PS4. ADVERTISING Making an official tie-in is one of the Commercial sales director Clare Dove Advertising director Andrew Church toughest challenges in all of gaming, and our Account manager Steve Pyatt Advertising manager Michael Pyatt tale of new studio Fireforge’s efforts with For Ad enquiries contact [email protected] MARKETING this one begins on p52.