'PV Driven Dew-Point Cooling for Australia'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Maine's Renewable Resources Through Appropriate Technology

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1986 Sun, Wind, Water, Wood : Using Maine's Renewable Resources Through Appropriate Technology State of Maine Office of Energy Resources Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Education Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation State of Maine Office of Energy Resources, "Sun, Wind, Water, Wood : Using Maine's Renewable Resources Through Appropriate Technology" (1986). Maine Collection. 64. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/64 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sun, Wind, Water, Wood- Using Maine's Renewable Resources through Appropriate Technology STATE OF MAINE Office of Energy Resources State House Station 53 Augsta, Maine 04333 phone (207) 289-3811 Acknowledgements We wish to thank the participants in these projects for their help in preparing this publication: Roger Bickford, Monmouth; Dan Boisclair, University of Maine, Portland; William Carr, University of Maine, Orono; Sandra Dickson, Port Clyde; Lawrence Gamble, Hampden; Captain Havilah Hawkins, Camden; Chris Heinig, Harpswell; Dr. Gordon Johnston, Sanford; Paul Jones, Mechanic Falls; Robert and Susanne Kelly, Lowell; William Kreamer, St. Joseph, Michigan; Jay LeGore, Liberty; Lloyd Lund, Waldoboro; Allen Pinkham, Damariscotta; Arthur Shute, East Sebago; George Sprowl, Searsmont; Peter Talmage, Kennebunkport; Lloyd Weaver, Topsham; Roger and Cheryl Willis, Bar Harbor. This publication has been funded by a grant from the United States Department of Energy, Appropriate Technology Information Dissemination Program, grant number DE-FG1-83R122245, and with support from the Maine Office of Energy Resources. -

XP Convection Heater

XP Convection Heater Heat Sync The Norseman™ XP Series convection heater is designed Length for freeze protection of control enclosures or other confined areas characterized by poor natural circulation and where explosive substances are present. As a precaution against excessive convector temperatures the unit comes standard with two thermostats. One thermostat is factory preset to limit the convector temperature to the maximum allowed for the temperature code classification. The second thermostat is also L nonadjustable and is set to control the space temperature Figure 18 Norseman™ XP between 0°C to 16°C (32°F to 60°F). (Refer to TABLE 13 and TABLE 14) Units are available from 50 watts to 600 watts. Applications 5.5” (139.7 mm) The heaters are designed for space heating where potentially explosive substances are or may be present. Typical applications include: • control cabinets and small enclosures • storage rooms for paints and cleaners 2.625” • grain elevators (66.7 mm) • flour mills 5.25” (133.35 mm) • spray booths • gas plants Figure 19 Norseman™ Figure 20 Norseman™ XP Side View XP1-1007T3B Shown • pump houses • marine and offshore Construction and Installation • oil platforms • cleaning and dyeing plants The Norseman™ XP explosion-proof convection heaters utilize unique copper free aluminum extruded ® Selection of Temperature Code convector and the patented x-Max terminal housing. Large convector surface area and high mass fins ensure Refer to the atmospheric condition table (TABLE 2) at the safe and efficient low temperature heat transfer to the beginning of this catalog for detailed selection data for the environment. Convectors are black anodized to resist temperature code. -

Eb0726 1980.Pdf

Owen Osborne, Extension Energy Specialist b1!11~~~· Hi ugh J. Hansen, Extension Agricultural Engineer II I • i,. r ..... - ..... ..... ...- ... Oregon State University Fireplaces are aesthetically appealing to many peo ple. Because of nostalg'ia, or for reasons of intuitive common sense, homeowners have for years been demanding open fireplaces in their homes. Estimates indicate that over half the single family -homes in the U.S. have at least one fireplace and about one million new fireplaces are being installed annually. Home buyers express an overwhelming preference fo ~ built-in fireplaces and a brisk business ·is being done in pre fabricated units. Where wood fuel is plentiful and inex pensive, people are turning down central heating sys tem thermostats, stoking up fireplaces and learning Fireplace Heat Distribution and Efficiency through personal experience the pros and cons of Heat, by laws of physics, is transfenred by three heating with wood. methods-convection, radiation and conduction. Con A fireplace must generally be considered a luxury, vection is transferring of heat from one area to another since its primary value is enhancing the appearance by moving air. Radiation is movement of infrared and atmosphere of a room. Fireplaces are basically electromagnetic rays through air with virtually no low-efficiency home heating units (only about 10% warming of the air but warming of any objects when efficient) unless extensive modifications are made in the rays stri·ke them. Sunlight is an example of radi their design and/ or operation to reduce the amount of ant heat. Conduction is transfer of heat along a solid heat lost up the chimney. -

Heating Report

Heating Report 1475 - St Paul’s Church, Finchley Rev 3.0 / 18th March 2020 1475 – St Pauls Church Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................. 2 2. The Existing Building and Heating System ........... 3 3. Sustainability Aims ................................................. 11 4. Lean Energy Saving Options ................................. 12 5. Heating .................................................................... 16 6. Conclusion ............................................................... 25 7. Appendix A Further Heating Information ...........26 8. Appendix B – Selection of Electric Radiant Heaters ................................................................... 28 9. Appendix C – The Rejected Shortlisted Electric Radiant Heating Option ......................................... 32 Audit History Rev Date of Status Issued Checked Summary Issue By By of Changes 3.0 18/03/2020 FINAL MJS - Conclusion Updated 2.0 07/02/2020 FOR MJS - Conclusion COMMENT Added 1.0 15/01/2020 DRAFT MJS - © Skelly & Couch /1475-SAC-RPT-Heating Options Report /Rev 3.0 1 1475 – St Pauls Church 1. Introduction This report has been prepared by Skelly and Couch Ltd to inform St The sustainability goals are informed by Skelly & Couch’s knowledge of: The calculated heat losses were then used to calculate predicted energy Pauls Church, located on Long Lane, Finchley, of their heating and use and the results cross checked against actual gas consumption data • the minimum requirements set out in the current building insulation options. The church was built in 1886, reordered in 1979 and for the church to check accuracy of any assumptions. Average annual in 2008 an extension was built along the South Eastern face. The study regulations; energy usages have been calculated using ‘Degree Days’ data from considers the most efficient way to heat the original church building • the current UK construction industry best practice for CIBSE A Guide, for average temperatures in London (Heathrow) 1982- only. -

PROPANE CONSTRUCTION CONVECTION HEATER OWNER’S MANUAL for More Information, Visit

PROPANE CONSTRUCTION CONVECTION HEATER OWNER’S MANUAL For more information, visit www.desatech.com Variable 40-60-80,000 Btu/Hr Model OFF LO HI MED IMPORTANT: Read and understand this manual before assembling, starting, or servicing heater. Improper use of heater can cause serious injury. Keep this manual for future reference. GENERAL HAZARD WARNING: FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THE PRECAUTIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS PROVIDED WITH THIS HEATER, CAN RESULT IN DEATH, SERIOUS BODILY INJURY AND PROPERTY LOSS OR DAMAGE FROM HAZARDS OF FIRE, EXPLOSION, BURN, ASPHYXIATION, CARBON MONOX- IDE POISONING, AND/OR ELECTRICAL SHOCK. ONLY PERSONS WHO CAN UNDERSTAND AND FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS SHOULD USE OR SERVICE THIS HEATER. IF YOU NEED ASSISTANCE OR HEATER INFORMATION SUCH AS AN INSTRUCTIONS MANUAL, LABELS, ETC. CONTACT THE MANUFACTURER. TABLE OF CONTENTS SAFETY INFORMATION ............................................................ 2 STORAGE................................................................................... 5 PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION ..................................................... 3 MAINTENANCE .......................................................................... 6 UNPACKING ............................................................................... 3 SPECIFICATIONS ...................................................................... 6 THEORY OF OPERATION ......................................................... 3 REPLACEMENT PARTS ............................................................ 6 PROPANE SUPPLY ................................................................... -

Norseman 2014

Product Guide Forced Air Unit Heaters Convection Heaters Thermostats Thermostat Installation Kits Convection Heaters XB Explosion-Proof Natural Convection Heaters • Designed for heating spaces where explosive substances may be present, such as storage rooms for paints and cleaners, grain elevators, gas plants, and more. • Offers a state of the art design, featuring CCI Thermal's unique copper-free aluminum extruded convecter and patented x-Max® terminal housing. • Models offered in 50 to 5130W and from 120 to 600V. • CCSAUS approved for Class 1, Division 1 & 2, Groups A, B, C & D; Class II, Division 1 & 2, Groups E, F, G; Class III, Division 1 & 2 at a temperature code of T2D, T3B, T4A or T6. • CE/ATEX for II 2 G, Ex d IIC T3 or T4 Gb. XPA Explosion-Proof Natural Convection Panel Heaters • Designed specifically for freeze protection of control enclosures and other confined areas characterized by poor natural circulation where potentially explosive substances may be present, such as control cabinets, small enclosures and more. • Comes factory-wired to a explosion-proof junction box and includes a mounting bracket and hardware. • Models offered in 50 to 700 W and from 120 to 240V. • CCSAUS approved for Class 1, Divisions 1 & 2, Groups A, B, C & D at a temperature code of T2D, T3, T3B or T4. • Available in three different size extrusions. Forced Air Unit Heaters XGB Explosion-Proof Forced Air Unit Heaters • Designed for heating industrial spaces where potentially explosive substances may be present, such as water and sewage treatment plants, oil refineries, compressor stations and more. -

Performance Studies on Automated Solar Powered Air Cooler/ Air Heater

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 01, JANUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Performance Studies On Automated Solar Powered Air Cooler/ Air Heater Manish Nayak, Manjunath H N, Madhusudhan M Abstract: So many types of air cooler cum air heating system available in the market which is working on AC and DC power. Here we design a model which is automated using micro controller arduino nano and temperature sensor. Which is maintains the temperature automatic. In this paper we collect power from sun light and stored in lead acid battery during a day times and also we save the energy by using controller. Whenever we required this power is used to operate the air collar/air heating system. Evaporative cooling accomplished by direct contact of water with flowing air. When hot and dry air passed through the soaked pad temperature of air get diminished with increase of specific humidity, moisture content in a pad get evaporated by use of latent heat of evaporation from air and heating of air is done by convective heating. Required temperature conditions are programmed in microcontroller to accomplish the satisfying cooling/heating effect. Index Terms: DC fan, temperature sensor, water pump, solar panel and microcontroller, Coil. —————————— —————————— 1. INTRODUCTION are used to balance the room temperature and humidity to For all forms of energy the main source is solar power. The comfortable region. Cooling is done by adiabatic manner [5], existence of energy to environment is developing to promise and heating by forced convection method.it consists of fan that the standard life and healthy run of economy. -

Constant-Heat-Flux Surfaces

hol29362_Ch07 11/3/2008 15:0 336 7-4 Free Convection from Vertical Planes and Cylinders Figure 7-6 Free-convection heat transfer from horizontal isothermal cylinders. 10000 1000 100 d Nu 10 1 0.1 10 −10 10 −7 10 −4 1 103 106 109 1012 GrdPr Constant-Heat-Flux Surfaces Extensive experiments have been reported in References 25, 26, and 39 for free convection from vertical and inclined surfaces to water under constant-heat-flux conditions. In such experiments, the results are presented in terms of a modified Grashof number, Gr∗: 4 ∗ gβq x Gr = Gr Nu = w [7-30] x x x kν2 where qw = q/A is the heat flux per unit area and is assumed constant over the entire plate surface area. The local heat-transfer coefficients were correlated by the following relation for the laminar range: = hx = ∗ 1/5 5 ∗ 11; = Nuxf 0.60(Grx Prf ) 10 < Grx Pr < 10 qw const [7-31] kf ∗ It is to be noted that the criterion for laminar flow expressed in terms of Grx is not the same as that expressed in terms of Grx. Boundary-layer transition was observed to begin between ∗ = × 12 × 13 × 13 14 Grx Pr 3 10 and 4 10 and to end between 2 10 and 10 . Fully developed ∗ = 14 ∗ turbulent flow was present by Grx Pr 10 , and the experiments were extended up to Grx Pr = 1016. For the turbulent region, the local heat-transfer coefficients are correlated with = ∗ 1/4 × 13 ∗ 16; = Nux 0.17(Grx Pr) 2 10 < Grx Pr < 10 qw const [7-32] # 101675 Cust: McGraw-Hill Au: Holman Pg. -

Direct Fired Heaters Brochure

Direct Fired Heaters Convection Heater A convection style heater offers the benefits of a direct fired heater, while eliminating some of the drawbacks associated with radiant heat transfer. Radiant heat transfer can be undesirable in certain temperature sensitive applications as radiant heat transfer tends to be more intense and unevenly distributed around the coil surface. Sigma Thermal’s convection style direct fired heater utilizes a separate combustion chamber and flue gas recirculation to reduce combustion chamber temperatures to 1,400F, thereby minimizing the impact of radiant heat transfer to the process coil. Convection Heater Design Features Row by Row Sizing Method: This detailed siz- Advanced Control Systems: Complete control Typical Applications ing method allows for accurate prediction systems are engineered to optimize and precise control of heat flux and film system safety and performance. Sigma »» Natural»Gas»Heating temperatures on each individual tube row. thermal can supply simple and cost »» Crude»Oil»Heating Coil Configuration Flexibility: Coil flow path effective standard panels, as well as »» Regeneration»Gas»Heating and metallurgy are engineered for each full process automation and PLC based »» In»Line»Liquid»Heating customer’s process requirements. Sigma combustion control / BMS. »» In»Line»Gas»Heating Thermal has extensive experience in »» Thermal»Oil»Heating process coil design for multi-phase fluids, »» Other»Direct»Process»Heating viscous hydrocarbons, suspended solids, and various gaseous mixtures. Fuel Source and Burner Flexibility: Standard or engineered burner configurations are available for use with both traditional and alternative fuel sources. Low emissions burners can be supplied to meet all emis- sion requirements (e.g., Low NOx, Best Available Control Technology). -

Space Heater Guide Did You Know Heating Your Home with Electric Space Heaters Can Easily Double Or Triple Your Electric Bill If

Space Heater Guide Did you know heating your home with electric space heaters can easily double or triple your electric bill if you are not careful? Even though they are typically small in size, and often touted as 100% efficient, electric space heaters can use a lot of electricity. Most space heaters use on average 1,000 to 1,500 watts of electricity and cost about 13¢ an hour to operate. While that may not sound like much, it can add up quickly if heaters are left on for several hours a day. Leaving one space heater on for 8 hours a day for a period of one month could easily add an additional $30-$35 to your monthly electric bill. Following are some good tips to help manage your electric bill if you use electric space heaters in your home. • Do not heat rooms that are not in use. Space heaters should only be used in rooms you are occupying and should never be left unattended. Remember to turn off heaters when you leave a room to help you save money on your electric bill. • Appropriate uses for space heaters. Most space heaters work best in areas that can easily be closed off to retain heat, such as a small bedroom or office. They do not work well in areas that cannot be closed off to the rest of the home, or large rooms as the heat will dissipate away quickly. • Select the right space heater. Not all space heaters are created equal. Some space heaters are designed to evenly heat a whole room, while others are better at heating only what is directly in front of them. -

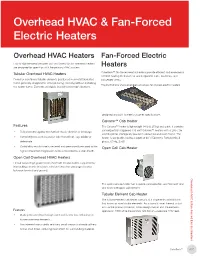

Catalog Section C, Page C6 for More Information the Left Or Right Side, Top Or Bottom

Overhead HVAC & Fan-Forced Electric Heaters Overhead HVAC Heaters Fan-Forced Electric Low to high temperature open coil and finned tubular overhead heaters are designed for operation with the primary HVAC system� Heaters Tubular Overhead HVAC Heaters Caloritech™ fan-forced electric heaters provide efficient and economical comfort heating for transit car use in operator cabs, lavatories, and Finned or non-finned tubular elements positioned in a metal fabricated passenger areas� frame generally designed for removal during servicing without disturbing The illustrations show examples of various fan-forced electric heaters the heater frame� Elements are rigidly braced to minimize vibrations� designed and built to meet customer specifications� Calvane™ Cab Heater Features The Calvane™ heater is lightweight 14 lb (6�35 kg) and quiet� It contains six horizontally staggered 333 watt Calvane™ heaters with a 250 c�f�m� • Fully protected against mechanical shock, vibration or breakage� centrifugal fan strategically placed in a brushed aluminum frame� The • Completely encased resistance wire that will not, sag, oxidize or heater is low profile, having a depth of 60” (1520 mm)� Rated 208V, 3 deteriorate� phase, 60 Hz, 2 kW� • Coiled alloy resistor wire is centered and permanently encased within Open Coil Cab Heater highly compacted magnesium oxide surrounded by a steel sheath� Open Coil Overhead HVAC Heaters Helical wound high grade nickel chromium resistant wires supported by interlocking ceramic insulators with four times the creepage distance between -

Radiant Convection Heater

Radiant Convection Heater INSTRUCTION MANUAL Model Number ERC24B AFTER SALES SUPPORT (AU) 1300 886 649 (NZ) 0800 836 761 Important Safety Instructions READ CAREFULLY AND KEEP FOR FUTURE REFERENCE Read this manual thoroughly before first use, even if you are familiar with this type of product. The safety precautions enclosed herein reduce the risk of fire, electric shock and injury when correctly adhered to. Make sure you understand all instructions and warnings. Keep the manual in a safe place for future reference, along with any warranty information, your purchase receipt and packaging. If you sell or transfer ownership of this product, please pass on these instructions to the new owner. Always follow basic safety precautions and accident prevention measures when using an electrical appliance, including the following: Electrical safety and cord handling • Voltage: Before plugging in the heater, make sure your outlet voltage and frequency correspond to the voltage stated on the appliance rating label. • Electrical outlet / circuit: Always plug this heater into a separate wall outlet socket that must be properly earthed. To ensure you do not overload the circuit, do not operate another high-wattage product on the same circuit. • Connection: To insert the plug, grasp it firmly and guide it into the outlet. • WARNING: No extension cord: Do not use this heater with an extension cord as this may overheat and cause a risk of fire. Do not use a plug adaptor. • Protect the power cord: – Do not operate the heater with the cord coiled up; always fully unwind. – Do not twist or kink the cord or let it touch heated surfaces.