Danieljohn.Pdf (3.2MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Polish Contribution to the UK War Effort in World War Two 3

DEBATE PACK CDP-0168 (2019) | 27 June 2019 Compiled by: Polish contribution to the Tim Robinson Nigel Walker UK war effort in World War Subject specialist: Claire Mills Two Contents Westminster Hall 1. Background 2 2. Press Articles 4 Tuesday 2 July 2019 3. Ministry of Defence 5 4. PQs 7 2.30pm to 4.00pm 5. Other Parliamentary material 9 Debate initiated by Daniel Kawczynski MP 5.1 Debates 9 5.2 Early Day Motions 9 6. Further reading 10 The proceedings of this debate can be viewed on Parliamentlive.tv The House of Commons Library prepares a briefing in hard copy and/or online for most non-legislative debates in the Chamber and Westminster Hall other than half-hour debates. Debate Packs are produced quickly after the announcement of parliamentary business. They are intended to provide a summary or overview of the issue being debated and identify relevant briefings and useful documents, including press and parliamentary material. More detailed briefing can be prepared for Members on request to the Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number CDP 2019/0168, 26 June 2019 1. Background After Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany, thousands of Polish military personnel escaped to France, and later the UK, where they made an invaluable contribution to the Allied war effort. In June 1940, the Polish Government in exile in the UK signed an agreement with the British Government to form an independent Polish Army, Air Force and Navy in the UK, although they remained under British operational command. -

[< OU 1 60433 >M

r [< OU_1 60433 >m OUP 68 1 1-1-68 2,(lio. OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No./l^* ST)* 2rGj Accession No. / Z 1 / , /) / * Author Title (J This book should be returned on or before the date f last marked below. GOD IS MY ADVENTURE books by the same author Minos the Incorruptible Pilsudski Pademwski Seven Thy Kingdom Come Search for Tomorrow Arm the Apostles Love for a Country Of No Importance We have seen Evil Hitler's Paradise The Fool's Progress Letter to Andrew GOD IS MY ADVENTURE a book on modern mystics masters and teachers by ROM LANDAU FABER AND FABER 24 Russell Square London Gratefully to B who taught me some of the best yet most painful lessons Fifst\/)ublished by Ivor Nicholson and Watson September Mcmxxxv Reprinted October Mcmxxxv November Mcmxxxv November Mcmxxxv February Mcmxxxvi September Mcmxxxvi December Mcmxxxvi June Mcmxxxix Transferred to Faber and Faber Mcmxli Reprinted Mcmxliii, Mcmxliv, Mcmxlv and Mcmliii Printed in Great Britain by Purnell and Sons Ltd., Paulton (Somerset) and London All Rights Reserved PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION is something sacrilegious in your intention of writing Theresuch a book,' said a friend and yet I went on with it. Since I was a boy I have always been attracted by those regions of truth that the official religions and sciences are shy of exploring. The men who claim to have penetrated them have always had for me the same fascination that famous artists, explorers or states- men have for others and such men are the subject of this book. -

Generate PDF of This Page

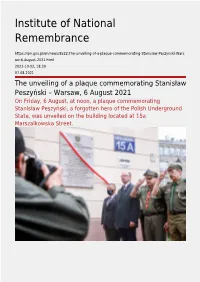

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8522,The-unveiling-of-a-plaque-commemorating-Stanislaw-Peszynski-Wars aw-6-August-2021.html 2021-10-02, 18:30 07.08.2021 The unveiling of a plaque commemorating Stanisław Peszyński – Warsaw, 6 August 2021 On Friday, 6 August, at noon, a plaque commemorating Stanisław Peszyński, a forgotten hero of the Polish Underground State, was unveiled on the building located at 15a Marszalkowska Street. Stanisław Peszyński was an associate of two successive Government Delegates for Poland: Minister Jan Piekałkiewicz (murdered by the Germans in June 1943) and Deputy Prime Minister Jan Stanisław Jankowski (arrested by the Soviet security services in March 1945, tried in the Moscow trial of the leaders of the Polish Underground State, and probably murdered in a Soviet prison in 1953), as well as head of the Control Section in the Delegation. He was in fact the chairman of the Supreme Chamber of Control (NIK) in the Polish Underground State. He was shot by the Germans on 6 August 1944. The plaque was unveiled by Deputy President of the Institute of National Remembrance Mateusz Szpytma, Ph.D., and the NIK’s President Marian Banaś. Before the ceremony, the IPN's 'History Point' Educational Center at 21/25 Marszałkowska Street hosted a meeting during which Professor Grzegorz Nowik, head of the Polish Scouting Association, talked about Stanisław Peszyński, and Professor Jacek Sawicki from the IPN’s Historical Research Office recalled what had happened in Warsaw on 5 and 6 August 1944. The participants also discussed the cooperation between the IPN and the NIK. -

Warsaw in Short

WarsaW TourisT informaTion ph. (+48 22) 94 31, 474 11 42 Tourist information offices: Museums royal route 39 Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street Warsaw Central railway station Shops 54 Jerozolimskie Avenue – Main Hall Warsaw frederic Chopin airport Events 1 ˚wirki i Wigury Street – Arrival Hall Terminal 2 old Town market square Hotels 19, 21/21a Old Town Market Square (opening previewed for the second half of 2008) Praga District Restaurants 30 Okrzei Street Warsaw Editor: Tourist Routes Warsaw Tourist Office Translation: English Language Consultancy Zygmunt Nowak-Soliƒski Practical Information Cartographic Design: Tomasz Nowacki, Warsaw Uniwersity Cartographic Cathedral Photos: archives of Warsaw Tourist Office, Promotion Department of the City of Warsaw, Warsaw museums, W. Hansen, W. Kryƒski, A. Ksià˝ek, K. Naperty, W. Panów, Z. Panów, A. Witkowska, A. Czarnecka, P. Czernecki, P. Dudek, E. Gampel, P. Jab∏oƒski, K. Janiak, Warsaw A. Karpowicz, P. Multan, B. Skierkowski, P. Szaniawski Edition XVI, Warszawa, August 2008 Warsaw Frederic Chopin Airport Free copy 1. ˚wirki i Wigury St., 00-906 Warszawa Airport Information, ph. (+48 22) 650 42 20 isBn: 83-89403-03-X www.lotnisko-chopina.pl, www.chopin-airport.pl Contents TourisT informaTion 2 PraCTiCal informaTion 4 fall in love wiTh warsaw 18 warsaw’s hisTory 21 rouTe no 1: 24 The Royal Route: Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street – Nowy Âwiat Street – Royal ¸azienki modern warsaw 65 Park-Palace Complex – Wilanów Park-Palace Complex warsaw neighborhood 66 rouTe no 2: 36 CulTural AttraCTions 74 The Old -

Rom Landau Collection, 1899-1965

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft0199n4k4 No online items Guide to the Rom Landau Collection Processed by Special Collections staff Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 2001 Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Rom Landau Mss 63 1 Collection Guide to the Rom Landau Collection, 1899-1965 Collection number: Mss 63 Department of Special Collections, Davidson Library, University of California, Santa Barbara Contact Information: Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html Processed by: Special Collections staff Date Completed: 06 August 2001 Encoded by: David C. Gartrell © 2001 Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Rom Landau Collection, Date (inclusive): 1899-1965 Collection Number: Mss 63 Creator: Landau, Rom, 1899- Extent: ca. .4 linear feet (1 box) Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara. Library. Department of Special Collections Santa Barbara, California 93106-9010 Physical Location: Annex. Language: English. Access Restrictions None. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. -

Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War Against Stronger States?

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2004 Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States? Sang Hyun Park University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Park, Sang Hyun, "Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2346 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sang Hyun Park entitled "Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Robert A. Gorman, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Mary Caprioli, Donald W. Hastings, April Morgan, Anthony J. Nownes Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sang-Hyun Park entitled “Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?” I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. -

Discover Warsaw

DISCOVER WARSAW #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw WELCOME TO WARSAW! If you are looking for open people, fascinating history, great fun and unique flavours, you've come to the right place. Our city offers you everything that will make your trip unforgettable. We have created this guide so that you can choose the best places that are most interesting for you. The beautiful Old Town and interactive museums? The wild river bank in the heart of the city? Cultural events? Or maybe pulsating nightlife and Michelin-star restaurants? Whatever your passions and interests, you'll find hundreds of great suggestions for a perfect stay. IT'S TIME TO DISCOVER WARSAW! CONTENTS: 1. Warsaw in 1 day 5 2. Warsaw in 2 days 7 3. Warsaw in 3 days 11 4. Royal Warsaw 19 5. Warsaw fights! 23 6. Warsaw Judaica 27 7. Fryderyk Chopin’s Warsaw 31 8. The Vistula ‘District’ 35 9. Warsaw Praga 39 10. In the footsteps of socialist-realist Warsaw 43 11. What to eat? 46 12. Where to eat? 49 13. Nightlife 53 14. Shopping 55 15. Cultural events 57 16. Practical information 60 1 WARSAW 1, 2, 3... 5 2 3 5 5 1 3 4 3 4 WARSAW IN 1 DAY Here are the top attractions that you can’t miss during a one-day trip to Warsaw! Start with a walk in the centre, see the UNESCO-listed Old Town and the enchanting Royal Łazienki Park, and at the end of the day relax by the Vistula River. -

(1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) As Political Myths

Department of Political and Economic Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki The Battle Backwards A Comparative Study of the Battle of Kosovo Polje (1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) as Political Myths Brendan Humphreys ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in hall XII, University main building, Fabianinkatu 33, on 13 December 2013, at noon. Helsinki 2013 Publications of the Department of Political and Economic Studies 12 (2013) Political History © Brendan Humphreys Cover: Riikka Hyypiä Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN-L 2243-3635 ISSN 2243-3635 (Print) ISSN 2243-3643 (Online) ISBN 978-952-10-9084-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9085-1 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2013 We continue the battle We continue it backwards Vasko Popa, Worriors of the Field of the Blackbird A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that “dream factory” takes over and employs countless mythical motifs – the fight between hero and monster, initiatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures and images (the maiden, the hero, the paradisiacal landscape, hell and do on). Even reading includes a mythological function, only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an ‘escape from time’ comparable to the ‘emergence from time’ effected by myths. -

KING HASSAN II: Morocco’S Messenger of Peace

KING HASSAN II: Morocco’s Messenger of Peace BY C2007 Megan Melissa Cross Submitted to the Department of International Studies and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts _________________________ Chair _________________________ Co-Chair _________________________ Committee Member Date Defended: ___________ The Thesis Committee for Megan Melissa Cross certifies That this is the approved version of the following thesis: KING HASSAN II: Morocco’s Messenger of Peace Committee: _________________________ Chair _________________________ Co-Chair _________________________ Committee Member Date approved: ___________ ii ABSTRACT Megan Melissa Cross M.A. Department of International Studies, December 2007 University of Kansas The purpose of this thesis is to examine the roles King Hassan II of Morocco played as a protector of the monarchy, a mediator between Israel and the Arab world and as an advocate for peace in the Arab world. Morocco’s willingness to enter into an alliance with Israel guided the way for a mutually beneficial relationship that was cultivated for decades. King Hassan II was a key player in the development of relations between the Arab states and Israel. His actions illustrate a belief in peace throughout the Arab states and Israel and also improving conditions inside the Moroccan Kingdom. My research examines the motivation behind King Hassan II’s actions, his empathy with the Israeli people, and his dedication to finding peace not only between the Arab states and Israel, but throughout the Arab world. Critics question the King’s intentions in negotiating peace between Israel and the Arab states. -

Gurdjieff and Music

Gurdjieff and Music 300854 Aries Book Series Texts and Studies in Western Esotericism Editor Marco Pasi Editorial Board Jean-Pierre Brach Wouter J. Hanegraaff Andreas Kilcher Advisory Board Allison Coudert – Antoine Faivre – Olav Hammer Monika Neugebauer-Wölk – Mark Sedgwick – Jan Snoek György Szőnyi – Garry Trompf VOLUME 20 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/arbs 300854 Gurdjieff and Music The Gurdjieff/de Hartmann Piano Music and Its Esoteric Significance By Johanna J.M. Petsche LEIDEN | BOSTON 300854 Cover Illustration: Photo reproduced with kind permission from Dorine Tolley and Thomas A.G. Daly. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petsche, Johanna J. M. Gurdjieff and music : the Gurdjieff/de Hartmann piano music and its esoteric significance / by Johanna J.M. Petsche. pages cm. -- (Aries book series ; v. 20) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-28442-5 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-28444-9 (e-book) 1. Gurdjieff, Georges Ivanovitch, 1872-1949. Piano music. 2. Gurdjieff, Georges Ivanovitch, 1872-1949. 3. Hartmann, Thomas de, 1885-1956. I. Title. ML410.G9772P47 2015 786.2092--dc23 2014038858 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1871-1405 ISBN 978-90-04-28442-5 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-28444-9 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. -

Defence Policy and the Armed Forces During the Pandemic Herunterladen

1 2 3 2020, Toms Rostoks and Guna Gavrilko In cooperation with the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung With articles by: Thierry Tardy, Michael Jonsson, Dominic Vogel, Elisabeth Braw, Piotr Szyman- ski, Robin Allers, Paal Sigurd Hilde, Jeppe Trautner, Henri Vanhanen and Kalev Stoicesku Language editing: Uldis Brūns Cover design and layout: Ieva Stūre Printed by Jelgavas tipogrāfija Cover photo: Armīns Janiks All rights reserved © Toms Rostoks and Guna Gavrilko © Authors of the articles © Armīns Janiks © Ieva Stūre © Uldis Brūns ISBN 978-9984-9161-8-7 4 Contents Introduction 7 NATO 34 United Kingdom 49 Denmark 62 Germany 80 Poland 95 Latvia 112 Estonia 130 Finland 144 Sweden 160 Norway 173 5 Toms Rostoks is a senior researcher at the Centre for Security and Strategic Research at the National Defence Academy of Latvia. He is also associate professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Univer- sity of Latvia. 6 Introduction Toms Rostoks Defence spending was already on the increase in most NATO and EU member states by early 2020, when the coronavirus epi- demic arrived. Most European countries imposed harsh physical distancing measures to save lives, and an economic downturn then ensued. As the countries of Europe and North America were cau- tiously trying to open up their economies in May 2020, there were questions about the short-term and long-term impact of the coro- navirus pandemic, the most important being whether the spread of the virus would intensify after the summer. With the number of Covid-19 cases rapidly increasing in September and October and with no vaccine available yet, governments in Europe began to impose stricter regulations to slow the spread of the virus.