8 Urologic Emergencies in Children: Special Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bladder & Cloacal Exstrophy

Bladder & Cloacal Exstrophy: A 30 Year Journey of Innovation Rosemary H. Grant, RN BSN Boston Childrens Hospital Department of Urology/ Surgical Programs 27th Annual APSNA Scientific Conference Palm Desert , California Bladder & Cloacal Exstrophy There are no disclosures Bladder & Cloacal Extrophy Objectives Identify 3 systems involved in the Exstrophy Complex Diagnosis Define the procedure for management of the exstrophied bladder State 2 components of psychosocial support for the Exstrophy Population 1 Exstrophy Complex Exstrophy – Epispadias (EEC): Classic Bladder Exstrophy Epispadias Cloacal Exstrophy (OEIS): Omphalocele Exstrophy Imperforate anus Spinal anomaly Exstrophy/Epispadias Complex (EEC) Incidence- 1:10,000- 1:50,000 live births 5:1 ratio of male- female births Embryology Typically occurs between 9 and 12 weeks gestation Cloacal membrane ruptures prematurely AFTER separation of the GI and GU tracts Presentation: Eversion of the bladder through an abdominal wall defect Exposure of the inner bladder mucosa Exposure of the dorsal urethra Lack of musculature in the anterior abdominal wall over the bladder Bladder is exposed and drains onto the abdomen Bladder Exstrophy Prenatal Diagnosis (Fetal US) Courtesy of Carol Barnewolt, MD 2 Bladder Exstrophy (Boy) Boy: Frontal view Umbilicus Bladder Low-lying umbilicus Urethral Exposed (inside-out) bladder Plate Urethra open on dorsum (top) Glans of the penis Penis Scrotum Bladder Exstrophy (Girl) Girl: Frontal view Umbilicus Bladder open on Bladder abdominal wall Urethral Urethra open -

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S. Tekgül (Chair), H.S. Dogan, E. Erdem (Guidelines Associate), P. Hoebeke, R. Ko˘cvara, J.M. Nijman (Vice-chair), C. Radmayr, M.S. Silay (Guidelines Associate), R. Stein, S. Undre (Guidelines Associate) European Society for Paediatric Urology © European Association of Urology 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Aim 7 1.2 Publication history 7 2. METHODS 8 3. THE GUIDELINE 8 3A PHIMOSIS 8 3A.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 8 3A.2 Classification systems 8 3A.3 Diagnostic evaluation 8 3A.4 Disease management 8 3A.5 Follow-up 9 3A.6 Conclusions and recommendations on phimosis 9 3B CRYPTORCHIDISM 9 3B.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 9 3B.2 Classification systems 9 3B.3 Diagnostic evaluation 10 3B.4 Disease management 10 3B.4.1 Medical therapy 10 3B.4.2 Surgery 10 3B.5 Follow-up 11 3B.6 Recommendations for cryptorchidism 11 3C HYDROCELE 12 3C.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 12 3C.2 Diagnostic evaluation 12 3C.3 Disease management 12 3C.4 Recommendations for the management of hydrocele 12 3D ACUTE SCROTUM IN CHILDREN 13 3D.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 13 3D.2 Diagnostic evaluation 13 3D.3 Disease management 14 3D.3.1 Epididymitis 14 3D.3.2 Testicular torsion 14 3D.3.3 Surgical treatment 14 3D.4 Follow-up 14 3D.4.1 Fertility 14 3D.4.2 Subfertility 14 3D.4.3 Androgen levels 15 3D.4.4 Testicular cancer 15 3D.5 Recommendations for the treatment of acute scrotum in children 15 3E HYPOSPADIAS 15 3E.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology -

Renal Agenesis, Renal Tubular Dysgenesis, and Polycystic Renal Diseases

Developmental & Structural Anomalies of the Genitourinary Tract DR. Alao MA Bowen University Teach Hosp Ogbomoso Picture test Introduction • Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney & Urinary Tract (CAKUT) Objectives • To review the embryogenesis of UGS and dysmorphogenesis of CAKUT • To describe the common CAKUT in children • To emphasize the role of imaging in the diagnosis of CAKUT Introduction •CAKUT refers to gross structural anomalies of the kidneys and or urinary tract present at birth. •Malformation of the renal parenchyma resulting in failure of normal nephron development as seen in renal dysplasia, renal agenesis, renal tubular dysgenesis, and polycystic renal diseases. Introduction •Abnormalities of embryonic migration of the kidneys as seen in renal ectopy (eg, pelvic kidney) and fusion anomalies, such as horseshoe kidney. •Abnormalities of the developing urinary collecting system as seen in duplicate collecting systems, posterior urethral valves, and ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Introduction •Prevalence is about 3-6 per 1000 births •CAKUT is one of the commonest anomalies found in human. •It constitute approximately 20 to 30 percent of all anomalies identified in the prenatal period •The presence of CAKUT in a child raises the chances of finding congenital anomalies of other organ-systems Why the interest in CAKUT? •Worldwide, CAKUT plays a causative role in 30 to 50 percent of cases of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), •The presence of CAKUT, especially ones affecting the bladder and lower tract adversely affects outcome of kidney graft after transplantation Why the interest in CAKUT? •They significantly predispose the children to UTI and urinary calculi •They may be the underlying basis for urinary incontinence Genes & Environment Interact to cause CAKUT? • Tens of different genes with role in nephrogenesis have been identified. -

OEIS Complex, a Case Report

Case Report iMedPub Journals Journal of Intensive and Critical Care 2016 http://www.imedpub.com ISSN 2471-8505 Vol. 2 No. 1:4 DOI: 10.21767/2471-8505.100013 OEIS Complex, A Case Report Manassero-Morales G, Franco-Bustamante K, Matos-Rojas I Abstract National Institute of Child Health, San Borja, Introduction: The OEIS complex includes: Omphalocele, Exstrophy of the cloaca, Lima, Perú Imperforate anus, and Spinal defects. The OEIS complex affects 1 in 200,000 to 400,000 pregnancies and its etiology is uncertain. The purpose is to present our experience in this unusual coexistence of malformations never reported in Latin Corresponding author: America. Manassero-Morales G Clinical Case: A male infant, three months of age, diagnosed at birth with omphalocele, cloacal exstrophy, double hemi bladder, rectum and anal atresia, [email protected] bilateral clubfeet and lumbosacral bifid spine. Abdominal MRI confirmed clinical findings and also showed horseshoe kidney, bilateral enlarged renal pelvis. Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño-San Borja, Lumbosacral spine MRI revealed lipomeningocele, hypoplastic sacrum and pubic Lima, Perú agenesia. In the first two days of life, this patient underwent several surgical procedures. Currently (3 months old) is waiting for further surgical reconstruction. Conclusion: The case described meets the clinical criteria for OIES complex; in the Citation: Manassero-Morales G, Franco- absence of a family history that could suggest a pattern of Mendelian inheritance Bustamante K, Matos-Rojas I .OEIS Complex, and normal cytogenetic study. We conclude that this is an isolated case of probable A Case Report. J Intensive & Crit Care 2016, multifactorial inheritance. -

Irish Rare Kidney Disease Network (IRKDN)

Irish Rare kidney Disease Network (IRKDN) Others Cork University Mater, Waterford University Dr Liam Plant Hospital Galway Dr Abernathy University Hospital Renal imaging Dr M Morrin Prof Griffin Temple St and Crumlin Beaumont Hospital CHILDRENS Hospital Tallaght St Vincents Dr Atiff Awann Rare Kidney Disease Clinic Hospital University Hospital Prof Peter Conlon Dr Lavin Prof Dr Holian Little Renal pathology Lab Limerick University Dr Dorman and Hospital Dr Doyle Dr Casserly Patient Renal Council Genetics St James Laboratory Hospital RCSI Dr Griffin Prof Cavaller MISION Provision of care to patients with Rare Kidney Disease based on best available medical evidence through collaboration within Ireland and Europe Making available clinical trials for rare kidney disease to Irish patients where available Collaboration with other centres in Europe treating rare kidney disease Education of Irish nephrologists on rare Kidney Disease. Ensuring a seamless transition of children from children’s hospital with rare kidney disease to adult centres with sharing of knowledge of rare paediatric kidney disease with adult centres The provision of precise molecular diagnosis of patients with rare kidney disease The provision of therapeutic plan based on understanding of molecular diagnosis where available Development of rare disease specific registries within national renal It platform ( Emed) Structure Beaumont Hospital will act as National rare Kidney Disease Coordinating centre working in conjunction with a network of Renal unit across the country -

Epispadias and Exstrophy

Epispadias and Exstrophy How is bladder exstrophy/epispadias treated? Bladder exstrophy is managed surgically. One technique is to close it in stages. First the bladder and bladder neck are closed, the bones of the pelvis are brought together, and the urethra is made. Secondary surgeries are required in the first year of life to reconstruct the penis and to manage inguinal hernias. In some instances the entire reconstruction including bladder, bladder neck, pelvic bones, and urethra are closed all in one surgery. Both these techniques require an experienced surgeon. Both techniques will require the child to go to the intensive care unit (ICU) immediately after surgery for a few days. The child is then followed for a few more days in the regular (non ICU) part of the pediatric hospital before the child is ready for discharge. Hernia repairs will need to be performed later and often the child has vesicoureteral reflux, which may need to be corrected. Depending on the initial size of the bladder continence can be achieved up to 70% of the time. However, often these children require further surgeries to manage the bladder neck and treat incontinence. Often these children need to catheterize. Epispadias occurs in males and females. It occurs in bladder exstrophy and without bladder exstrophy. In males it occurs when the penis does not properly form a tube out to the tip of the penis and the opening is along the shaft of the penis. It can occur from the tip of the penis all the way to the bladder and depending on the position of the opening it can be associated with urinary incontinence (urine leakage) and retrograde ejaculation (ejaculate going backward toward the bladder instead out the urethra). -

Appendix 3.1 Birth Defects Descriptions for NBDPN Core, Recommended, and Extended Conditions Updated March 2017

Appendix 3.1 Birth Defects Descriptions for NBDPN Core, Recommended, and Extended Conditions Updated March 2017 Participating members of the Birth Defects Definitions Group: Lorenzo Botto (UT) John Carey (UT) Cynthia Cassell (CDC) Tiffany Colarusso (CDC) Janet Cragan (CDC) Marcia Feldkamp (UT) Jamie Frias (CDC) Angela Lin (MA) Cara Mai (CDC) Richard Olney (CDC) Carol Stanton (CO) Csaba Siffel (GA) Table of Contents LIST OF BIRTH DEFECTS ................................................................................................................................................. I DETAILED DESCRIPTIONS OF BIRTH DEFECTS ...................................................................................................... 1 FORMAT FOR BIRTH DEFECT DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................................................. 1 CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM ....................................................................................................................................... 2 ANENCEPHALY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 ENCEPHALOCELE ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 HOLOPROSENCEPHALY............................................................................................................................................................. -

OEIS Complex (Omphalocele, Exstrophy of Bladder, Imperforate Anus and Spine Defects)

Journal of Human Anatomy OEIS Complex (Omphalocele, Exstrophy of Bladder, Imperforate Anus and Spine Defects) Kandavadivelu M* Mini Review PSG Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, India Volume 2 Issue 1 Received Date: January 22, 2018 *Corresponding author: Manickavasuki Kandavadivelu, PSG Institute of Medical Published Date: February 16, 2018 Sciences & Research, India, Tel: 9842766782; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract OEIS complex comprises of a combination of defects including Omphalocele, Exstrophy of bladder, Imperforate anus and Spinal defects. The prenatal ultrasound of the fetus may show grossly malformed fetus. It may be provisionally diagnosed as OEIS complex by Non - visualization of urinary bladder, presence of Omphalocele, limb and spine defects in the ultrasound. During dissection of the fetus short umbilical cord and adherent amniotic membrane may be observed. On opening the sac, liver, intestines and cloaca were found to be contents. External genitalia and anal opening may not be seen. There may be an imperforate anus. Fetal spine may shows scoliosis, hemivertebrae or any other vertebral anomalies. Prognosis of the fetus depends on the associated anomalies and its severity. Serial ultrasonography may be used to accurately diagnose abdominal wall defect in utero and to diagnose the associated anomalies. The possibility of correction of the defects after birth of the fetus or termination of the fetus may be determined by the Ultrasound. Keywords: Exstrophy of bladder; Omphalocele; Scoliosis; Umbilical cord Introduction of the herniation of the abdominal contents into the proximal part of the umbilical cord. Herniation of the OEIS complex comprises of a combination of defects intestines into the cord occurs in approximately 1 in 5000 including Omphalocele, Exstrophy of bladder, Imperforate births and herniation of liver and intestines occur in 1 in anus and Spine defects. -

An Omphalocele Exstrophy Imperforate Anus Spinal Abnormality (OEIS) Variant

Delayed recognition of bladder exstrophy and persistent cloaca: An Omphalocele exstrophy imperforate anus spinal abnormality (OEIS) Variant Itunu O. Arojo MD, Lynn L. Woo MD. HPI • Newborn term infant with abnormal prenatal ultrasound on 22- week anatomy scan. – Widened pubic diastasis – Dilated rectosigmoid colon – Mild polyhydramnios – Distended bladder in pelvis protruding into the omphalocele • Empties during exam • Mother aged 31 G3P3, otherwise healthy • Prenatal MRI obtained to confirm findings 2 Physical Exam • Omphalocele • Asymmetric labia/clitoral tissue • Fistulous connection to the bladder • Imperforate anus with a single mucosal-lined opening in perineum 6 Diagnostic evaluation • Cystoscopy/EUA – cloacal malformation – Appearance of an intact urethra/bladder neck complex – vaginal duplication – fistulous tract to the rectum 7 Diagnostic evaluation • Cystogram – smooth-walled bladder without evidence of reflux • Spinal ultrasound was normal. 8 • DOL 4 – Omphalocele rupture revealed bladder exstrophy 9 Hospital course • She underwent a diverting colostomy on DOL 4. • Discharged home with seran wrap coverage and prophylatic antibiotics • Cloacal repair and closure of bladder exstrophy is planned at age 6 months of age. 10 Discussion • Cloacal exstrophy is a rare and complex congenital anomaly • Incidence of 1/200,000-400,000 live birth • Occurs along a spectrum • Associated omphalocele often contains bowel or liver • Prenatal diagnosis of exstrophy is difficult to make. Often a diagnosis of omphalocele/gastroschisis made and the exstrophy overlooked . 11 Conclusion • This case highlights the complexity associated with diagnosis of exstrophy- epispadias complex. Despite advances in prenatal imaging, diagnosis of this condition relies upon physical examination with the knowledge that each presentation can be different; not fitting in one box. -

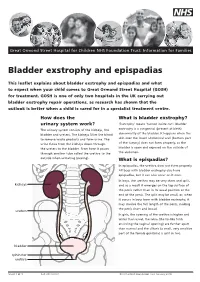

Bladder Exstrophy and Epispadias

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust: Information for Families Bladder exstrophy and epispadias This leaflet explains about bladder exstrophy and epispadias and what to expect when your child comes to Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) for treatment. GOSH is one of only two hospitals in the UK carrying out bladder exstrophy repair operations, as research has shown that the outlook is better when a child is cared for in a specialist treatment centre. How does the What is bladder exstrophy? urinary system work? ‘Exstrophy’ means ‘turned inside out’. Bladder The urinary system consists of the kidneys, the exstrophy is a congenital (present at birth) bladder and ureters. The kidneys filter the blood abnormality of the bladder. It happens when the to remove waste products and form urine. The skin over the lower abdominal wall (bottom part urine flows from the kidneys down through of the tummy) does not form properly, so the the ureters to the bladder. From here it passes bladder is open and exposed on the outside of through another tube called the urethra to the the abdomen. outside when urinating (peeing). What is epispadias? In epispadias, the urethra does not form properly. All boys with bladder exstrophy also have epispadias, but it can also occur on it own. In boys, the urethra may be very short and split, kidneys and as a result it emerges on the top surface of the penis rather than in its usual position at the end of the penis. The split may be small, or, when it occurs in boys born with bladder exstrophy, it may involve the full length of the penis, making the penis short and broad. -

Abdominal Wall Defects

FETAL MRI OF ABDOMINAL WALL DEFECTS Teresa Victoria MD PhD Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia PRENATAL WORK UP AWD • AWD range • very simple (umbilical cord defect) • highly complex (cloacal exstrophy or LBWC) • all: abd content herniation through ventral wall • Correct dx, vital: 1. Appropriate management and referral 2. Accurate parental counseling KEY TO DX: UMBILICAL CORD INSERTION OBJECTIVES • Fetal MR review of abdominal wall defects 1. Umbilical cord defect 2. Gastroschisis 3. Omphalocele 4. Bladder exstrophy 5. Cloacal exstrophy 6. Limb body wall complex 1. UMBILICAL CORD DEFECT Defect of the abdominal wall muscles Skin covered SSFP ssTSE UMBILICAL CORD DEFECT OB MUST KNOW! or the bowel will be cut ssTSE T1FLASH 2. GASTROSCHISIS • Full thickness abd. wall defect • Usually RIGHT-sided paraumbilical defect Survival: 95% if uncomplicated SSFP GASTROSCHISIS-COMPLICATED ssTSE T1FLASH • Survival decreases (~70%) if: ischemia perforation atresia 3. OMPHALOCELE • Herniation abd contents into base of umb cord • Usually membrane covered Peritoneum Wharton’s jelly Amnion • Etiology, uncertain • Cord insertion, at base/apex of AWD 20 wk fetus OMPHALOCELE • Herniation abd contents into base of umb cord • Usually membrane covered Peritoneum Wharton’s jelly Amnion • Etiology, uncertain • Cord insertion, at base/apex of AWD OMPHALOCELE-”TYPES” Giant omph Bowel only with ascites (>75% herniated liver) OMPHALOCELE “TYPES” Ruptured OMPHALOCELE “TYPES” L B Ruptured Syndromic Beckwith-Wiedemann 4. BLADDER EXSTROPHY • Failure of ant abd wall and ant bladder wall to close normally • AWD INFERIOR to the cord insertion site • Hallmark of BE: “Absent” urinary bladder INFRAumbilical “mass” represents the everted bladder Bladder is everted and open to the abd wall Urine is released directly to amniotic cavity • Normal amniotic fluid and hindgut • Usually abnormal genitalia BLADDER EXSTROPHY L 29 wk fetus BLADDER EXSTROPHY ♀ 29 wk fetus BLADDER EXSTROPHY 29 wk fetus ♂ 5. -

Congenital Anomalies of the Kidneys, Collecting System, Bladder, and Urethra

Congenital Anomalies of the Kidneys, Collecting System, Bladder, and Urethra Halima S. Janjua, MD,* Suet Kam Lam, MD, MPH, MS,† Vedant Gupta, DO,‡ Sangeeta Krishna, MD† *Center for Pediatric Nephrology, †Department of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, ‡Department of Pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic Children’s, Cleveland, OH Education Gap Several congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract are incidental findings. An understanding of when to suspect and how to diagnose, manage, and use timely and appropriate investigations and consults is necessary. Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to: 1. Develop an awareness of various congenital anomalies of the renal system, including embryology, prevalence, and risk factors. 2. Describe the clinical presentation and management of renal and urinary tract anomalies, including which anomalies warrant further evaluation and the timing and utility of imaging modalities. 3. Develop an awareness of genetic syndromes affecting the kidneys and urinary tract with associated extrarenal manifestations. INTRODUCTION Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) include a wide spectrum of anomalies, with a reported incidence of up to 2% of births. (1) CAKUT account for almost one-fourth of all birth defects. (2) These are major AUTHOR DISCLOSURE Drs Janjua, Lam, Gupta, and Krishna have disclosed no causes of kidney disease in children and account for more than 40% of end-stage financial relationships relevant to this article. renal disease (ESRD). CAKUT are usually detected by routine prenatal ultraso- This commentary does not contain a nography, although some cases are not diagnosed until adulthood. (3) discussion of an unapproved/investigative When renal disease is suspected, a complete physical examination should be use of a commercial product/device.