(Enaρ Centre D’Alerte Et De Prévention Des Conflits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

Burundi: the Issues at Stake

BURUNDI: THE ISSUES AT STAKE. POLITICAL PARTIES, FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND POLITICAL PRISONERS 12 July 2000 ICG Africa Report N° 23 Nairobi/Brussels (Original Version in French) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................i INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 I. POLITICAL PARTIES: PURGES, SPLITS AND CRACKDOWNS.........................1 A. Beneficiaries of democratisation turned participants in the civil war (1992-1996)3 1. Opposition groups with unclear identities ................................................. 4 2. Resorting to violence to gain or regain power........................................... 7 B. Since the putsch: dangerous games of the government................................... 9 1. Purge of opponents to the peace process (1996-1998)............................ 10 2. Harassment of militant activities ............................................................ 14 C. Institutionalisation of political opportunism................................................... 17 1. Partisan putsches and alliances of convenience....................................... 18 2. Absence of fresh political attitudes......................................................... 20 D. Conclusion ................................................................................................. 23 II WHICH FREEDOM FOR WHAT MEDIA ?...................................................... 25 A. Media -

Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS for PEACE an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY FILIP REYNTJENS BURUNDI: Acknowledgements PROSPECTS FOR PEACE Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of Trócaire and all the orga- Internally displaced © Minority Rights Group 2000 nizations and individuals who gave financial and other people. Child looking All rights reserved assistance for this Report. after his younger Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- sibling. commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- This Report has been commissioned and is published by GIACOMO PIROZZI/PANOS PICTURES mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the For further information please contact MRG. issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in ISBN 1 897 693 53 2 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. ISSN 0305 6252 Published November 2000 MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert Typeset by Texture readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Kat- Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. rina Payne (Commissioning Editor) and Sophie Rich- mond (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR Burundi: FILIP REYNTJENS teaches African Law and Politics at A specialist on the Great Lakes Region, Professor Reynt- the universities of Antwerp and Brussels. -

The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi

Human Rights as Means for Peace : the Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi Author: Fidele Ingiyimbere Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2475 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE-SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTY S.T.L THESIS Human Rights as Means for Peace The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi By Fidèle INGIYIMBERE, S.J. Director: Prof David HOLLENBACH, S.J. Reader: Prof Thomas MASSARO, S.J. February 10, 2011. 1 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 0 General Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 CHAP. I. SETTING THE SCENE IN BURUNDI ......................................................................... 8 I.1. Historical and Ecclesial Context........................................................................................... 8 I.2. 1972: A Controversial Period ............................................................................................. 15 I.3. 1983-1987: A Church-State Conflict .................................................................................. 22 I.4. 1993-2005: The Long Years of Tears................................................................................ -

Will Hutus and Tutsis Live Together Peacefully ?

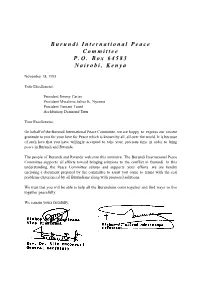

B u r u n d i I n t e r n a t i o n a l P e a c e C o m m i t t e e P . O . B o x 6 4 5 8 3 N a i r o b i , K e n y a November 18, 1995 Your Excellencies. President Jimmy Carter President Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere President Tumani TourŽ Archbishop Desmond Tutu Your Excellencies, On behalf of the Burundi International Peace Committee, we are happy to express our sincere gratitude to you for your love for Peace which is known by all, all over the world. It is because of such love that you have willingly accepted to take your precious time in order to bring peace in Burundi and Rwanda. The people of Rurundi and Rwanda welcome this initiative. The Burundi International Peace Committee supports all efforts toward bringing solutions to the conflict in Burundi. In this understanding, the Peace Committee salutes and supports your efforts. we are hereby enclosing a document prepared by the committee to assist you come to terms with the real problems experienced by all Burundians along with proposed solutions. We trust that you will be able to help all the Burundians come together and find ways to live together peacefully. We remain yours faithfully, WILL HUTUS AND TUTSIS LIVE TOGETHER PEACEFULLY ? Introduction More than two years have passed since the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye of Burundi. Since then, many people have lost their lives and continue to die. One wonders whether it will be possible again for Hutus and Tutsis to live together peacefully. -

List of Prime Ministers of Burundi

SNo Phase Name Took office Left office Duration Political party 1 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) Joseph Cimpaye 26-01 1961 28-09 1961 245 days Union of People's Parties 2 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) Prince Louis Rwagasore 28-09 1961 13-10 1961 15 days Union for National Progress 3 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) André Muhirwa 20-10 1961 01-07 1962 254 days Union for National Progress 4 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) André Muhirwa 01-07 1962 10-06 1963 344 days Union for National Progress 5 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pierre Ngendandumwe 18-06 1963 06-04 1964 293 days Union for National Progress 6 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Albin Nyamoya 06-04 1964 07-01 1965 276 days Union for National Progress 7 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pierre Ngendandumwe 07-01 1965 15-01 1965 10 days Union for National Progress 8 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pié Masumbuko 15-01 1965 26-01 1965 11 days Union for National Progress 9 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Joseph Bamina 26-01 1965 30-09 1965 247 days Union for National Progress 10 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Prince Léopold Biha 13-10 1965 08-07 1966 268 days Union for National Progress 11 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Michel Micombero 11-07 1966 28-11 1966 140 days Union for National Progress 12 Republic of Burundi Albin Nyamoya 15-07 1972 05-06 1973 326 days Union for National Progress 13 Republic of Burundi Édouard Nzambimana 12-11 1976 13-10 1978 1 year, 335 days Union for -

Assassinat Du Premier Ministre Du Burundi, Pierre Ngendandumwe Cinquante Ans Après Par Perpétue Nshimirimana, Le 15 Janvier 2015

Assassinat du Premier ministre du Burundi, Pierre Ngendandumwe Cinquante ans après Par Perpétue Nshimirimana, le 15 janvier 2015 Contribution à la Commission Vérité-Réconciliation et au Mécanisme de Justice Transitionnelle L’année 2015 est une année particulière dans l’Histoire du Burundi. Elle marque, en effet, le cinquantième anniversaire du déclenchement des premiers assassinats en masse des citoyens et des intellectuels burundais ayant en commun le fait d’appartenir à l’ethnie Hutu. Cet anniversaire invite tous les Barundi épris de justice et de paix à marquer un temps d’arrêt pour une pensée envers toutes les victimes innocentes du pays. Aujourd’hui, le public attend, précisément, de la part des dirigeants du Burundi officiel, de vrais gestes symboliques et concrets dans le but d’honorer leur mémoire et de lutter contre l’oubli suivi d’une impunité invraisemblable. L’année 2015 donne l’occasion, aussi, de se souvenir en particulier de ces illustres disparus, les vrais Bâtisseurs du Burundi moderne. Il faut les mettre en lumière pour assurer la pérennité de leurs idées et de leurs projets. Au moment où le pays se dote, enfin, des membres constitutifs de la Commission Vérité et Réconciliation (C.V.R.)1, le Burundi doit regarder en face son passé et délivrer l’entière vérité à sa population en souffrance depuis si longtemps. De nombreuses familles sont dans l’attente d’explications sur l’étendue du mal répandu en toute conscience et avec détermination. Le temps de la réhabilitation des personnes injustement accusées puis assassinées dans la foulée, au cours de l’année 1965, est arrivé. -

The Origin and Persistence of State Fragility in Burundi

APRIL 2018 The origin and persistence of state fragility in Burundi Janvier D. Nkurunziza Abstract State fragility in Burundi has been a cause, and consequence, of the country’s political instability. Since independence, Burundi has endured six episodes of civil war, two major foiled coup d’états, and five coup d’états that have led to regime change. The root cause of state fragility is traced back to divisive practices introduced by the colonial power, which have since been perpetuated by post-colonial elites. This political volatility has generated persistent cycles of violence, resulting in the collapse of the country’s institutions and economy, even after the negotiation of the Arusha Agreement. This has led to mass migration of Burundi’s people and the emergence of a large refugee population, dispersed among neighbouring states and far away. Therefore, state fragility in Burundi is first and foremost the result of the strategies and policies of its political leaders, who are motivated by personal interests. Political capture calls into question the legitimacy of those in power, who feed state fragility through rent extraction, corruption, and mismanagement. This has had vast economic consequences, including slow growth, an underdeveloped private sector, an unstable investment landscape, and severe financial constraints. For reconciliation to be achieved, justice needs to be afforded to those who have encountered repression from the state, thereby breaking the cycle of violence. What’s more, Burundi needs strong and long-term engagement of the international community for the successful implementation of reforms, as well as the provision of technical and financial resources, to embark on a prosperous and peaceful path. -

ECFG-Burundi-Apr-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to help prepare you for deployment to culturally complex environments and successfully achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information it contains will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain necessary skills to achieve mission success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1: Introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Burundi Part 2: Presents “Culture Specific” Burundi, focusing on unique cultural features of Burundian society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN News © Jane Some). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

GENERAL A/1C€,6 S E B LY 25 January 1G6l a S M ENGLISH OBIGINAL: I'ae$CE

NAT'ONS GENERAL A/1C€,6 S E B LY 25 January 1g6l A S M ENGLISH OBIGINAL: I'AE$CE Sixteenth session Agenda iten 49 QUESTION OF :THE I'UTURE OF IUANDA-URTJNDI Report of the United" Nations Connnission for Ruanda-Urundi on tb.e assassination of the Prime Minister of Burundi t A/5a86 Xng]lsh I TABTE OF CONTENTS laragraphs l,etter of transroittal Introduction f _ IO I. Chronofogical- account of the Conmission!s novenents, actions and" intervi.ews . , . ll_20 II. Terms of reference of the Coomission . ZI - jO IfI. Facts and circr$stances surxound-i-ng the prime Ministerrg death IV. Various opinions col_lected in Eurundi 12-\J Annexes r. srrfimaries of and rer-evant extrects from documents subnitted to the Conmission and annexed h€reto II. Xxplanatory note concernj_ng the ca6e of Frince Louis Rwagasore, Prlne Minister of the Governnxent of Burundi, addressed tc Mr. Max I{, Dorslnvill_e III. Conmunication dated. JO October 196l frotx the Legisl-atj.ve Agsenbly of Burundi concexni-ng the political situation in Burundi rv. Report subni-tted by the security conxxission to the Legisrative As sembl_y of Burundl on 28 October 1961 v. Additional- note supprementing the report of the security cccrni.ssion subnitted to the Legislative Assenbl-y of Burundi for approval on 28 October 1!61 VI. Letter dated 1 Novenxber 1961 fron the Vice Chalrnan of the parti ddmocrate ch"dtien VIL Intervlew with l4r, Kageorgis VIII. Interview with Mx. Iatrou IX. fnterview with lvir. Antoine Nahiuana X. Interviev with Mr. Jean-Baltiste Ntakiyica XI. -

Wounded Memories: Perceptions of Past Violence in Burundi and Perspectives for Reconciliation

Wounded Memories: Perceptions of past violence in Burundi and perspectives for reconciliation Patrick Hajayandi Wounded Memories: Perceptions of past violence in Burundi and perspectives for reconciliation Research Report Patrick Hajayandi Published by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation 105 Hatfield Street, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001, South Africa www.ijr.org.za ISBN: 978-1-928332-51-0 Text © 2019 Institute for Justice and Reconciliation All rights reserved. Orders to be placed with the IJR: Tel: +27 (21) 202 4071 Email: [email protected] The contributors to this publication write in their personal capacity. Their views do not necessarily reflect those of their employers or of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. The front cover photograph shows the rocks at Kiganda. These are connected to the signing of a peace treaty between the King of Burundi, Mwezi Gisabo, and the German officer Captain von Beringe in 1903. Designed and produced by COMPRESS.dsl | www.compressdsl.com Table of contents Foreword 1 Acknowledgements 3 Research team 5 Acronyms 6 Executive summary 7 Chapter 01 Introduction 11 Chapter 02 Historical background 14 2.1. Winds of change 17 2.2. First elections and first signs of political instability 18 2.3. Rwagasore at loggerheads with the colonial administration 19 2.4. The thorny road to independence 21 2.5. Major violent crises in the post-independence era 23 2.5.1. The 1965 crisis and ethnic radicalization 24 2.5.2. The 1972 Genocide against the Bahutu 24 2.5.3. 1988: The Ntega and Marangara crisis 26 2.5.4. The 1990’s reforms and resistances 27 2.5.5. -

![International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5984/international-commission-of-inquiry-for-burundi-final-report-1-2-3985984.webp)

International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2

[International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2 Contents Part I: Introduction I. Creation of the Commission II. The Commission’s Mandate III. General Methodology IV. Activities of the Commissions A. 1995 B. 1996 V. Difficulties in the Commission’s Work A. The time elapsed since the events under investigation B. Ethnic polarization in Burundi C. The security situation in Burundi D. Inadequacy of resources VI. Acknowledgements VII. Documents and Recordings Part II: Background I. Geographical Summary of Burundi II. Population III. Administrative Organization IV. Economic Summary V. Historical Summary VI. The Presidency of Melchior Ndadaye VII. Events After the Assassination Part III: Investigation of the Assassination I. Object of the Inquiry II. Methodology III. Access to Evidence IV. Work of the Commission V. The Facts According to Witnesses A. 3 July 1993 B. 10 July 1993 C. 11 October 1993 1 Note: This title is derived from information found at Part I:1:2 of the report. No title actually appears at the top of the report. 2 Posted by USIP Library on: January 13, 2004 Source Name: United Nations Security Council, S/1996/682; received from Ambassador Thomas Ndikumana, Burundi Ambassador to the United States Date received: June 7, 2002 D. Monday, 18 October 1993 E. Tuesday, 19 October 1993 F. Wednesday, 20 October 1993 G. Thursday, 21 October 1993, Midnight to 2 a.m. H. Thursday, 21 October 1993, 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. I. Thursday, 21 October 1993, 6 a.m. to noon J. Thursday, 21 October 1993, Afternoon VI. Analysis of Testimony VII.