The Paranormal Conceptualizations in Previous Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrayals of Religious Studies in Popular Culture Brian Collins Ohio University

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2018 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 6-2018 From Middlemarch to The aD Vinci Code: Portrayals of Religious Studies in Popular Culture Brian Collins Ohio University Kristen Tobey John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018 Part of the Religion Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Brian and Tobey, Kristen, "From Middlemarch to The aD Vinci Code: Portrayals of Religious Studies in Popular Culture" (2018). 2018 Faculty Bibliography. 55. https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018/55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2018 Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Middlemarch to The Da Vinci Code: Portrayals of Religious Studies in Popular Culture TEMPLE MIDDLEMARCH Directed by Michael Barrett Television serial Screen Media, 2017. 78 minutes Directed by Anthony Page BBC, 1994 DEXTER. SEASON SIX Created by James Manos Jr. MIDDLEMARCH: THE SERIES Showtime, 2011 Directed by Rebecca Shoptaw DEATH DU JOUR YouTube, 2017 By Kathy Reichs New York: Pocket Books, 1999 ANGELS & DEMONS Pp. 480. $17.19 By Dan Brown New York: Washington Square Press, 2006 [2000] THE BLACK TAPES Pp. 496. $17.00 Podcast. Created by Paul Bae and Terry Miles 2015–2017 THE DA VINCI CODE By Dan Brown. THE REAPING New York: Anchor Books, 2009 [2003] Directed by Stephen Hopkins Pp. 597. $9.99 Warner Brothers, 2007. 99 minutes THE LOST SYMBOL SINISTER By Dan Brown Directed by Scott Derickson New York: Anchor Books, 2012 [2009] Blumhouse Productions, 2012. -

The Body in Wellbeing Spirituality

JAY JOHNSTON The body in Wellbeing Spirituality Self, spirit beings and the politics of difference Introduction New religious movements of the nineteenth century—notably the Theo sophical Society and Spiritualism—endowed western culture with an ener getic concept of the self: that is, with a model of the body that proposed the individual to be constituted by a ‘spiritual’ or subtle substance. This model of the body—the subtle body—was not new to western esoteric traditions, however, its presentation at this time melded with subtle body schemes from Hindu traditions (primarily Yoga traditions) and provided the groundwork for the popularisation of a concept of the body and self as being comprised of an energetic anatomy. This model of the self has continued unabated into con temporary consumer culture and underpins the vast majority of mind–body concepts in Complementary and Alternative Medical (CAM) practices. This article is concerned with the subtle body models currently found in Wellbeing Spirituality healing modalities. In particular, it considers their ontological and metaphysical propositions with regard to an ethics of difference: both ener getic and cultural. Therefore, two distinct types of discourse will be examined and discussed: that of popular culture and that of Continental philosophy (especially feminist and poststructural). Both provide methods for under standing the enduring popularity of subtle body concepts of the self and the challenging ethical relations that the model presupposes. ‘Difference’ herein refers to the term’s use in the Continental philosophic al tradition, in particular following the thought of Emmanuel Levinas in the proposition of a radical difference, or alterity. -

Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids

Ziptales Advanced Library Worksheet 2 Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids ‘What is a myth? It is a story that pretends to be real, but is in fact unbelievable. Like many urban myths it has been passed around (usually by word of mouth), acquiring variations and embellishments as it goes. It is a close cousin of the tall tale. There are mythical stories about almost any aspect of life’. What do we get when urban myths meet the animal kingdom? We find a branch of pseudoscience called cryptozoology. Cryptozoology refers to the study of and search for creatures whose existence has not been proven. These creatures (or crytpids as they are known) appear in myths and legends or alleged sightings. Some examples include: sea serpents, phantom cats, unicorns, bunyips, giant anacondas, yowies and thunderbirds. Some have even been given actual names you may have heard of – do Yeti, Owlman, Mothman, Cyclops, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster sound familiar? Task 1: Choose one of the cryptids from the list above (or perhaps one that you may already know of) and write an informative text identifying the following aspects of this mythical creature: ◊ Description ◊ Features ◊ Location ◊ First Sighting ◊ Subsequent Sightings ◊ Interesting Facts (e.g. how is it used in popular culture? Has it been featured in written or visual texts?) Task 2: Cryptozoologists claim there have been cases where species now accepted by the scientific community were initially considered urban myths. Can you locate any examples of creatures whose existence has now been proven but formerly thought to be cryptids? Extension Activities: • Cryptozoology is called a ‘pseudoscience’ because it relies solely on anecdotes and reported sightings rather than actual evidence. -

Book Section Reprint the STRUGGLE for TROGLODYTES1

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 6:33-170 (2017) Book Section Reprint THE STRUGGLE FOR TROGLODYTES1 Boris Porshnev "I have no doubt that some fact may appear fantastic and incredible to many of my readers. For example, did anyone believe in the existence of Ethiopians before seeing any? Isn't anything seen for the first time astounding? How many things are thought possible only after they have been achieved?" (Pliny, Natural History of Animals, Vol. VII, 1) INTRODUCTION BERNARD HEUVELMANS Doctor in Zoological Sciences How did I come to study animals, and from the study of animals known to science, how did I go on to that of still undiscovered animals, and finally, more specifically to that of unknown humans? It's a long story. For me, everything started a long time ago, so long ago that I couldn't say exactly when. Of course it happened gradually. Actually – I have said this often – one is born a zoologist, one does not become one. However, for the discipline to which I finally ended up fully devoting myself, it's different: one becomes a cryptozoologist. Let's specify right now that while Cryptozoology is, etymologically, "the science of hidden animals", it is in practice the study and research of animal species whose existence, for lack of a specimen or of sufficient anatomical fragments, has not been officially recognized. I should clarify what I mean when I say "one is born a zoologist. Such a congenital vocation would imply some genetic process, such as that which leads to a lineage of musicians or mathematicians. -

The Sherpa and the Snowman

THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN Charles Stonor the "Snowman" exist an ape DOESlike creature dwelling in the unexplored fastnesses of the Himalayas or is he only a myth ? Here the author describes a quest which began in the foothills of Nepal and led to the lower slopes of Everest. After five months of wandering in the vast alpine stretches on the roof of the world he and his companions had to return without any demon strative proof, but with enough indirect evidence to convince them that the jeti is no myth and that one day he will be found to be of a a very remarkable man-like ape type thought to have died out thousands of years before the dawn of history. " Apart from the search for the snowman," the narrative investigates every aspect of life in this the highest habitable region of the earth's surface, the flora and fauna of the little-known alpine zone below the snow line, the unexpected birds and beasts to be met with in the Great Himalayan Range, the little Buddhist communities perched high up among the crags, and above all the Sherpas themselves that stalwart people chiefly known to us so far for their gallant assistance in climbing expeditions their yak-herding, their happy family life, and the wav they cope with the bleak austerity of their lot. The book is lavishly illustrated with the author's own photographs. THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN "When the first signs of spring appear the Sherpas move out to their grazing grounds, camping for the night among the rocks THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN By CHARLES STONOR With a Foreword by BRIGADIER SIR JOHN HUNT, C.B.E., D.S.O. -

Sunlite 2 6.Pdf

SUNlite Shedding some light on UFOlogy and UFOs VOICES FROM THE WOODS When we got within a 50 meter distance. The object was producing red and blue light. The blue light was steady and projecting under the object. It was lighting up the area directly under extending a meter or two out. At this point of positive identification I relayed to CSC, SSgt Coffey. Positive sighting of object...colour of lights and that it was definitely mechanical in nature. This is the closest point Penniston relayed that he was close enough to the object to determine that it that I was near the object at any point. We then proceeded after it. It moved in a was definitely a mechanical object. He stated he was within approximately 50 zig-zagging manner back through the woods then lost sight of it. - Jim Penniston meters....Each time Penniston gave me the indication that he was about to reach January 1981 statement the area where the lights were, he would give an extended estimated location. He eventually arrived at a “beacon light”, however, he stated that this was not the light or lights he had originally observed. He was instructed to return. - J. D. Chandler January 1981 statement We climbed over the fence and started heading towards the red and blue lights and they just disappeared. Once we reached the farmer’s house we could see a beacon going around so we went towards it. We followed it for about 2 miles be- fore we could see it was coming from a lighthouse. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

ANG 5012, Section 6423 Spring 2017 FANTASTIC ANTHROPOLOGY and FRINGE SCIENCE

ANG 5012, section 6423 Spring 2017 FANTASTIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND FRINGE SCIENCE Time: Mondays, periods 7-9 (1:55 – 4:55) Place: TUR 2303 Instructor: David Daegling, Turlington B376 352-294-7603 [email protected] Office Hours: M 10:30 – 11:30 AM; W 1:00 – 3:00 PM. COURSE OBJECTIVES: This course examines the articulation and perpetuation of so-called paranormal and fringe scientific theories concerning the human condition. We will examine these unconventional claims with respect to 1) underlying belief systems, 2) empirical and logical foundations, 3) persistence in the face of refutation, 4) popular treatment by mass media and 5) institutional reaction. The course is divided into five parts. Part I explores forms of inquiry and considers the demarcation of science from pseudoscience. Part II concerns unconventional theories of human evolution. Part III investigates unorthodox ideas of human biology. Part IV examines claims of extraterrestrial and supernatural contact in the world today. Part V further scrutinizes institutional reaction to fringe science, popular coverage of science, and the culture of science in the contemporary United States. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Attendance is mandatory. Unexcused absences (i.e., other than medical or family emergency) result in a half grade reduction of your final grade. Participation in group and class discussions is required (50% of your final grade). In addition, written work is required for each of the five parts of the course (50% of your grade). These will take the form of essays and short papers to be completed concurrently with our discussions of these topics. Late papers are subject to a full letter grade reduction. -

Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: a Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 5 9-1-1996 Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: A Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Shamanic wisdom, parapsychological research and a transpersonal view: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15(3), 30–55.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15 (3). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol15/iss3/5 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAMANIC WISDOM, PARAPSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND A TRANSPERSONAL VIEW: A CROSS-CULTURAL ' PERSPECTIVE LARISSA VILENSKAYA PSI RESEARCH MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA, USA There in the unbiased ether our essences balance against star weights hurled at the just now trembling scales. The ecstasy of life lives at this edge the body's memory of its immutable homeland. -Osip Mandelstam (1967, p. 124) PART I. THE LIGHT OF KNOWLEDGE: IN PURSUIT OF SLAVIC WISDOM TEACHINGS Upon the shores of afar sea A mighty green oak grows, And day and night a learned cat Walks round it on a golden chain. -

Reptilians Are a Race of Lizard People of Unknown Origin

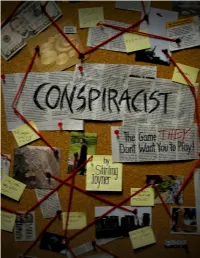

[title page, cover goes here] CREDITS Special thanks to Brian Williamson for being a great conversation partner and friend. Without you, this game would not be nearly as good. Concept, Design, and Writing: Stirling Joyner Editing: Caroline Harbour and Morgan Rawlinson Layout: John Fischer Aesthetic Advice: Morgan Rawlinson Cover Art: Stirling Joyner & Morgan Rawlinson Playtesting: Josie Joyner, Darcy Joyner, Brian Williamson, Garrett Gaunch, Elizabeth Williamson, Jeff Seitz, Dan Schaeffer Third-Party Images Used in Cover: Public Domain: Five dollar bill, Crop circles (Jabberocky), UFO CC BY-SA 3.0: Lizard (Ksenija Putilin) Fair Use: Newspaper clippings (Chicago Tribune), Warning lable, Reptilian secret service agent (YouTuber Reptillian Resistance), Google Earth image of Area 51 (DigitalGlobe, Google) CC BY 4.0: CC BY-SA button License: This roleplaying game and its cover art are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Under this license, you are free to copy, share, and remix all the content in this book for any purpose, even commercially. Under the following conditions: 1. You attribute Stirling Joyner. 2. You license any derivative works under the same license. Support Me: I released this game for free. If you like it and want to help me make more, please become a supporter on Patreon or send me a donation on PayPal. You can also pay what you want for this game on DriveThruRPG. • Patreon Link: patreon.com/sjrpgdesign • PayPal Link: paypal.me/sjrpgdesign • DriveThruRPG Link: drivethrurpg.com/browse.php?keywords=stirling+joyner Thank you Dan Shauer (DrLeaf), Johnathan & Jenn Madera, Austin Farrow, and Keller Scholl for supporting me on Patreon already! 1 I stumbled out of the crashed alien spacecraft and toward the secret government bunker that housed the real Statue of Liberty. -

Evidence-Based Alternative Medicine?

(YLGHQFH%DVHG$OWHUQDWLYH0HGLFLQH" .LUVWLQ%RUJHUVRQ 3HUVSHFWLYHVLQ%LRORJ\DQG0HGLFLQH9ROXPH1XPEHU$XWXPQ SS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2,SEP )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Dalhousie University (13 Jul 2016 15:54 GMT) 05/Borgerson/Final/502–15 9/6/05 6:55 PM Page 502 Evidence-Based Alternative Medicine? Kirstin Borgerson ABSTRACT The validity of evidence-based medicine (EBM) is the subject of on- going controversy.The EBM movement has proposed a “hierarchy of evidence,” ac- cording to which randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of RCTs provide the most reliable evidence concerning the efficacy of medical interventions. The evaluation of alternative medicine therapies highlights problems with the EBM hierarchy. Alternative medical researchers—like those in mainstream medicine—wish to evaluate their therapies using methods that are rigorous and that are consistent with their philosophies of medicine and healing.These investigators have three ways to relate their work to EBM.They can accept the EBM hierarchy and carry out RCTs when possible; they can accept the EBM standards but argue that the special characteristics of alternative medicine warrant the acceptance of “lower” forms of evidence; or they can challenge the EBM approach and work to develop new research designs and new stan- dards of evidence that reflect their approach to medical care. For several reasons, this last option is preferable. First, it will best meet the needs of alternative medicine prac- titioners. Moreover, because similar problems beset the evaluation of mainstream med- ical therapies, reevaluation of standards of evidence will benefit everyone in the med- ical community—including, most importantly, patients. -

Downloading Physics Preprints from Arxiv Would Be Quite Unaware That a Paper in General Physics Has to Be Treated Differently to Papers in Other Categories

1 The Ecology of Fringe Science and its Bearing on Policy Harry Collins, Andrew Bartlett and Luis Reyes-Galindo School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University1 emails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Introduction Fringe science has been an important topic since the start of the revolution in the social studies of science that occurred in the early 1970s.2 As a softer-edged model of the sciences developed, fringe science was a ‘hard case’ on which to hammer out the idea that scientific truth was whatever came to count as scientific truth: scientific truth emerged from social closure. The job of those studying fringe science was to recapture the rationality of its proponents, showing how, in terms of the procedures of science, they could be right and the mainstream could be wrong and therefore the consensus position is formed by social agreement. One outcome of this way of thinking is that sociologists of science informed by the perspective outlined above find themselves short of argumentative resources for demarcating science from non-science. The distinction with traditional philosophy of science, which readily demarcates fringe subjects such as parapsychology by referring to their ‘irrationality’ or some such, is marked.3 For the sociologist of scientific knowledge, that kind of demarcation comprises 1 This paper is joint work by researchers supported by two grants: ESRC to Harry Collins, (RES/K006401/1) £277,184, What is scientific consensus for policy? Heartlands and hinterlands of physics (2014-2016); British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellowship to Luis Reyes-Galindo, (PF130024) £223,732, The social boundaries of scientific knowledge: a case study of 'green' Open Access (2013-2016).