A Field Guide to Critical Thinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids

Ziptales Advanced Library Worksheet 2 Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids ‘What is a myth? It is a story that pretends to be real, but is in fact unbelievable. Like many urban myths it has been passed around (usually by word of mouth), acquiring variations and embellishments as it goes. It is a close cousin of the tall tale. There are mythical stories about almost any aspect of life’. What do we get when urban myths meet the animal kingdom? We find a branch of pseudoscience called cryptozoology. Cryptozoology refers to the study of and search for creatures whose existence has not been proven. These creatures (or crytpids as they are known) appear in myths and legends or alleged sightings. Some examples include: sea serpents, phantom cats, unicorns, bunyips, giant anacondas, yowies and thunderbirds. Some have even been given actual names you may have heard of – do Yeti, Owlman, Mothman, Cyclops, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster sound familiar? Task 1: Choose one of the cryptids from the list above (or perhaps one that you may already know of) and write an informative text identifying the following aspects of this mythical creature: ◊ Description ◊ Features ◊ Location ◊ First Sighting ◊ Subsequent Sightings ◊ Interesting Facts (e.g. how is it used in popular culture? Has it been featured in written or visual texts?) Task 2: Cryptozoologists claim there have been cases where species now accepted by the scientific community were initially considered urban myths. Can you locate any examples of creatures whose existence has now been proven but formerly thought to be cryptids? Extension Activities: • Cryptozoology is called a ‘pseudoscience’ because it relies solely on anecdotes and reported sightings rather than actual evidence. -

Reptilians Are a Race of Lizard People of Unknown Origin

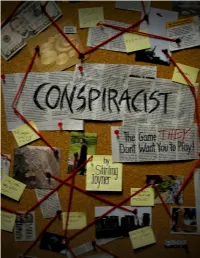

[title page, cover goes here] CREDITS Special thanks to Brian Williamson for being a great conversation partner and friend. Without you, this game would not be nearly as good. Concept, Design, and Writing: Stirling Joyner Editing: Caroline Harbour and Morgan Rawlinson Layout: John Fischer Aesthetic Advice: Morgan Rawlinson Cover Art: Stirling Joyner & Morgan Rawlinson Playtesting: Josie Joyner, Darcy Joyner, Brian Williamson, Garrett Gaunch, Elizabeth Williamson, Jeff Seitz, Dan Schaeffer Third-Party Images Used in Cover: Public Domain: Five dollar bill, Crop circles (Jabberocky), UFO CC BY-SA 3.0: Lizard (Ksenija Putilin) Fair Use: Newspaper clippings (Chicago Tribune), Warning lable, Reptilian secret service agent (YouTuber Reptillian Resistance), Google Earth image of Area 51 (DigitalGlobe, Google) CC BY 4.0: CC BY-SA button License: This roleplaying game and its cover art are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Under this license, you are free to copy, share, and remix all the content in this book for any purpose, even commercially. Under the following conditions: 1. You attribute Stirling Joyner. 2. You license any derivative works under the same license. Support Me: I released this game for free. If you like it and want to help me make more, please become a supporter on Patreon or send me a donation on PayPal. You can also pay what you want for this game on DriveThruRPG. • Patreon Link: patreon.com/sjrpgdesign • PayPal Link: paypal.me/sjrpgdesign • DriveThruRPG Link: drivethrurpg.com/browse.php?keywords=stirling+joyner Thank you Dan Shauer (DrLeaf), Johnathan & Jenn Madera, Austin Farrow, and Keller Scholl for supporting me on Patreon already! 1 I stumbled out of the crashed alien spacecraft and toward the secret government bunker that housed the real Statue of Liberty. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Monster Hunters Gather at Salt Fork State Park for Creature Weekend Conference

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 627 Wheeling Ave | Cambridge, OH 800‐933‐5480 | www.VisitGuernseyCounty.com CONTACT: Debbie Robinson ____________________________________________________________________________ MONSTER HUNTERS GATHER AT SALT FORK STATE PARK FOR CREATURE WEEKEND CONFERENCE The 6th annual Creature Weekend Conference being held at Salt Fork Lodge is scheduled for October 21, 2017 from 9:00AM to 6:30PM and features Adam Davies, Todd Neiss, Scott Mardis, Tom Sewid and Jeff Wamsley. Presentations will include discussions about Bigfoot, Lake Monsters, Mothman and other monsters mentioned in the tribal legends of the Pacific Northwest. The event also hosts Arts and Crafts vendors. Tickets are available at the door. Adults $30/Children 12 and under $10. Cambridge, Ohio, 10/18/2017: Creature Weekend is proud to announce that it will be holding its 2017 Cryptozoology Conference at Salt Fork State Park in Ohio on October 21, 2017 From 9:00AM to 10:00PM. This year’s speakers include Internationally reknown Adam Davies whose adventures can be seen on the show, “Finding Bigfoot : The Sumatra Expedition” and several episodes of “MonsterQuest”. He will be joined by longtime Bigfoot Researcher, Todd Neiss, Lake Monster expert Scott Mardis, Mothman Historian Jeff Wamsley and First Nations Bigfoot Researcher, Tom Sewid. Adam Davies will be talking about his two expeditions to Nepal in search of the Yeti, and will include insights into the T.V. programs he made there, History Channels' Abominable Snowman, and Josh Gates' Expedition Unknown on the Travel Channel. He will then move onto his current Bigfoot research in the U.S. Todd Neiss will be doing a presentation on his recent expedition into the Sasquatch Islands of the Broughton Archipelago in British Columbia. -

Guide to the Mandeville Collection in the Occult Sciences

GUIDE TO THE MANDEVILLE COLLECTION IN THE OCCULT SCIENCES in the Social Sciences, Health, and Education Library University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign http://www.library.illinois.edu/sshel/specialcollections/mandeville/mandgui.html TABLE OF CONENTS About the Collection ............................................................................................................ 1 Location of Materials ........................................................................................................... 2 Call Numbers ...................................................................................................................... 2 Astrology ............................................................................................................................. 3 Cereology ............................................................................................................................ 4 Cryptogeography ................................................................................................................. 5 Cryptozoology ..................................................................................................................... 5 Divination ............................................................................................................................ 6 Dreams ................................................................................................................................ 7 Esoteric Religion and Mysticism ........................................................................................ -

N: a Sea Monster of a Research Project

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2019 N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project Adrian Jay Thomson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomson, Adrian Jay, "N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 424. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/424 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N: A SEA MONSTER OF A RESEARCH PROJECT by Adrian Jay Thomson Capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS with a major in English- Creative Writing in the Department of English Approved: UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT SPRING2019 Abstract Ever since time and the world began, dwarves have always fought cranes. Ever since ships set out on the northern sea, great sea monsters have risen to prey upon them. Such are the basics of life in medieval and Renaissance Scandinavia , Iceland, Scotland and Greenland, as detailed by Olaus Magnus' Description of the Northern Peoples (1555) , its sea monster -heavy map , the Carta Marina (1539), and Abraham Ortelius' later map of Iceland, Islandia (1590). I first learned of Olaus and Ortelius in the summer of 2013 , and while drawing my own version of their sea monster maps a thought hit me: write a book series , with teenage characters similar to those in How to Train Your Dragon , but set it amongst the lands described by Olaus , in a frozen world badgered by the sea monsters of Ortelius. -

These Times for 1966

THE WORLD IN PERSPECTIVE BY GORDON M. HYDE HEN the British electronics en- signals have been sent, and then re- of the system, one might wonder Wgineer Arthur C. Clarke predicted turned with a spread that covers one whether the gospel—the good news— in 1945 that man could put a satellite third of the globe. And this, say the will be given worldwide dissemination. into orbit above the earth in such a way delighted engineers, is but the begin- And if so, by whom will it be spoken? that it would hold a fixed position in ning. More and more sophisticated The gospel commission to go into relationship to the earth, and actually packages of electronic wizardry will all the world and preach the gospel calculated that it should orbit at 22,- soon be "on location" above the earth, and to make disciples of all nations 300 miles, men wrote him off as a making it possible to beam multiple- comes inevitably to mind as these fairly wild science-fiction writer. Clarke signal TV, radio, or telephone com- "heavenly" messengers take up their did prove to be an effective writer, but munications to any spot on the earth. stations in the sky. Will men permit the in May, 1965, his fiction turned to fact The rapid development of such a everlasting gospel of the love of God to in the launching of a stationary satel- world-embracing system of communi- be proclaimed to every nation, kindred, lite. cation has inevitat ly aroused plenty tongue, and people? Or will these de- When Clarke made his calculations of international reaction and has given vices of man's God-given genius be put twenty years ago, there was no rocket the Western World a new channel for to purely secular uses for national ad- more powerful than the German V-2, matching the propaganda attempts of vantage? and it could climb only 100 miles. -

Science and Pseudo-Science Class Survey Form

Science and Pseudo-Science Survey (anonymous)- please do not sign your name Chem 199, Fall/2004 True Probably Probably Not True Not True True Acupuncture (Chi energy manipulation) Alligators in New York City sewers Alien abductions Astrology (personality prediction by birth date) Bad luck (black cats, broken mirrors, etc) Bermuda triangle effects Biorhythms (predictable personality cycles) Body memories (memory without the brain) Body-typing and personality Chiropractic Cryptozoology (e.g., Loch Ness, Big Foot) Crystal ball and tarot card reading Clairvoyance (prediction of the future) Demon possession Déjà vu experiences of another life Dowsing (for water, gold, etc.) ESP in animals ESP in twins Faith healing Fire walking (requires special mental state) Glossolalia (speaking in tongues) Ghosts, spirits, demons Graphology (handwriting analysis) Healing power of religious icons Homeopathy Hypnosis, Mesmerism Iridology (personality from eye colors, etc) Intelligent design/creation science/ Raelianism Kirlian auras Lie detector tests (Polygraph) Lourdes, etc (Religious Miracles) Mind reading/telepathy Mental imagery for improving sports performance Near-death experiences (NDEs) New Age therapies - crystals, orgone boxes, etc. Numerology / Kabalarian name analysis Out of body experiences Placebo effects Psychokinesis (movement by mental power) Pyramid power, healing powers, construction by aliens Reincarnation, existence of past lives Quantum basis for consciousness Recovered memories, hypnotic regression therapy Palm-reading, and tea leaves Poltergeists Repressed memory syndrome (hypnotic regression) Therapeutic touch Time travel Trancendental Meditation feats – floating on air UFO sightings as alien spacecraft Vampires, zombies Voodoo death, curses Witchcraft, spells, talking to the dead/spirits Yogi feats –stopping the heart, survive being buried alive. -

Gerard Croiset

Gerard Croiset: Investigation of the Mozart of "Psychic Sleuths"—Part I Critical examination of the evidence surrounding the cases of supposed crime-solving by the celebrated Dutch "clairvoyant" finds extraordinary differences between the claims and the facts. Piet Hein Hoebens First of two articles. The Dutchman Gerard Croiset, who died unexpectedly in July 1980, was undoubtedly one of the psychic superstars of the twentieth century. His mentor, Professor Wilhelm Tenhaeff, has called him the clairvoyant equivalent of Mozart or Beethoven. Tenhaeffs German colleague, Pro fessor Hans Bender, recently admitted that Croiset had been instrumental in transforming his belief in ESP into "an unshakable conviction." The obituaries published in the European press reflected the sensitive's unique reputation. According to the Amsterdam weekly Elsevier, the deceased had heralded a "new awareness of cosmic solidarity." The German para- scientific monthly Esotera ran a cover story lamenting the death of "the clairvoyant who never disappointed." A professor from the papal univer sity delivered the funeral oration. Croiset's career in the supernatural has been distinguished indeed. According to his biographers, he has solved some of the century's most baffling crimes, traced countless lost objects, and located hundreds of missing persons. His paranormal healing powers are said to have been on the Caycean level. He "excelled" at precognition and is credited with having accurately foretold future events on numerous occasions. Most of his remarkable feats, it is said, were performed under scientific supervision, which supposedly would make Croiset one of the most thoroughly tested sensitives since Mrs. Piper. Piet Hein Hoebens is an investigative journalist with the leading Dutch daily newspaper De Telegraff and a member of the Dutch section of CSICOP. -

Jeane Dixon and Prophecy

STATEMENT DJ010 Jeane Dixon And Prophecy JEANE DIXON, known to millions through her books and newspaper columns, claims to be a prophet of God, one who is doing “the Lord’s work.” In fact, she has gone so far as to say that “the same spirit that worked through Isaiah and John the Baptist also works through me.”1 This is quite a sobering claim. To be a prophet or seer of God, to speak for Him, and to reveal His will to the world is indeed a mighty calling. However, Jesus Himself warned us to beware of “false prophets” who would “mislead many.” (Matthew 24:11) How can we tell if someone is genuinely a prophet (or prophetess) of God? The best way to validate a person’s claim to a prophetic office is to compare him or her to the prophets of God found in the Scriptures. Since Jeane Dixon claims to be one such prophet, we must apply this test to her. CRITERIA FOR A PROPHET The first criterion for testing one claiming to be a prophet would obviously have to be a life that is pleasing to God. Obviously, someone who lived in rebellion to the Lord’s will, or who practiced things which God strongly condemns, could hardly be a reliable or true source of messages from God. Unfortunately, when one examines Jeane Dixon’s life, a rather significant problem emerges: Mrs. Dixon advocates astrology. Since her teen years, she has had an active interest in astrology and horoscopes, and she currently has a syndicated astrology column in numerous newspapers, across the country. -

Expansion of Consciousness: English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 063 292 TE 002 911 AUTHOR Kenzel, Elaine; Williams, Jean TITLE Expansion of Consciousness:.English. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 58p.; Authorized Course of InstructiGn for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 BC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; *Compositior (Literary); Comprehension Development; *Emotic il Experience; Group Experience; Individual Development; *Perception; Psychological Patterns; *Sensory Experience; Stimuli; *Stimulus Behavior; Thought Processes IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT A course that capitalizes on individual and group experiences and encourages students to expand their powers of observation and discernment is presented in the course, students analyzing their thoughts and translate them into written responses. The performance objectives are: A. Given opportunities to experience sensory and emotional stimuli, students will demonstrate an expanding awareness of each sense; B. Given opportunities to experience intellectual challenges, students will demonstrate an increasing comprehension with each situation; and C. Given opportunities to delve into moot phenomena, students will discern for themselves what is real and what is not real. Emphasis is placed on Teaching Strategies, which are approximately 178 suggestions tor the teacher's use in accomplishing the course objectives. Included are the course content and student and teacher resources.(Author/LS) ,, U.S. DEPARTMUIT OF HEALTH.EDUCATION St WELFARE I: OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THEPERSON DR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT,POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOTNECES. SARILT REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEOF EDU. CATION POSITION OR POLICY. AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE 3:0 EXPANSION OF CONSCIOUSNESS rims cm, 53.3.1.3.0 513.2 5113.10 533.4ao 5315ao 'PERMISSION TO-REPRODUCE THIS , -13 5116ao tiOPYRIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED = BY DADL-TcLICAtTY RIEV-1 r cm: TO ERIC AND OMANI/KOONS OPERATING ce) UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE U.S. -

ESP Your Sixth Sense by Brad Steiger

ESP Your Sixth Sense By Brad Steiger Contents: Book Cover (Front) (Back) Scan / Edit Notes Inside Cover Blurb 1 - Exploring Inner Space 2 - ESP, Psychiatry, and the Analyst's Couch 3 - Foreseeing the Future 4 - Telepathy, Twins, and Tuning Mental Radios 5 - Clairvoyance, Cops, and Dowsing Rod 6 - Poltergeists, Psychokinesis, and the Telegraph Key in the Soap Bubble 7 - People Who See Without Eyes 8 - Astral Projection and Human Doubles 9 - From the Edge of the Grave 10 - Mediumship and the Survival Question 11 - "PSI" and Psychedelics, and Mind-Expanding Drugs 12 - ESP in the Space Age 13 - "PSI" Research Behind the Iron Curtain 14 - Latest Experiments in ESP 15 - ESP - Test It Yourself ~~~~~~~ Scan / Edit Notes Versions available and duly posted: Format: v1.0 (Text) Format: v1.0 (PDB - open format) Format: v1.5 (HTML) Format: v1.5 (PDF - no security) Genera: ESP / Paranormal / Psychic Extra's: Pictures Included (for all versions) Copyright: 1966 / 1967 First Scanned: August - 11 - 2002 Posted to: alt.binaries.e-book Note: 1. The Html, Text and Pdb versions are bundled together in one zip file. 2. The Pdf files are sent as a single zip (and naturally does not have the file structure below) ~~~~ Structure: (Folder and Sub Folders) Main Folder - HTML Files | |- {Nav} - Navigation Files | |- {PDB} | |- {Pic} - Graphic files | |- {Text} - Text File -Salmun ~~~~~~~ Inside Cover Blurb Have you ever played a "lucky" hunch? Ever had a dream come true? Received a call or letter from someone you "just happened" to think of? Felt that "I've been here before" sensation known as Deja vu? Sensed what was "about to happen" even an instant before it occurred? Known what someone was about to say - or perhaps even spoken the exact words along with him? Then You May Be Using Your Sixth Sense Your Esp Without Even Realizing It! Recent research indicates that almost everyone possesses latent ESP powers.