Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chauri – Chaura Incident (1922)

Chauri – Chaura Incident (1922) CHAURI – CHAURA INCIDENT (1922) The Congress session held at Ahmedabad in December 1921, decided to launch a civil disobedience movement while reiterating its stand on the non-violent, non-cooperation movement of which Gandhi was the appointed leader. Before Gandhi could launch the civil disobedience movement, a mob at Chauri-Chaura led by Jawahar Yadav, near Gorakpur in the present day Uttar Pradesh, clashed with the police which opened fire. In retaliation, the mob burnt the police station and killed 22 policemen. This compelled Gandhi to call off the civil disobedience movement on 11 February 1922. Even so Gandhi was arrested and sentenced to 6 years imprisonment. The Chauri-Chaura incident convinced Gandhi that the nation was not yet ready for mass disobedience and he prevailed upon the Congress Working Committee in Bardoli on 12 February 1922, to call off the non-cooperation movement. Trade Unionism: Ideological Battleground Ideological differences in the labour movement began to appear within a few years after the birth of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC). The three distinct ideological groups in the trade union organization had entirely different views regarding the labour movement. These groups were; (i) Communists led by M. N. Roy and shripad Amrut Dange who wanted AIIUC to be affiliated to such --- international organizations as the League against imperialism and the Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat. The party ideology was supreme to these leaders and they took the unions as instruments for furthering it. (ii) Moderates led by N. M. Joshi and V. V. Giri, who wanted affiliation with the British labour Organization (BLO) and the international Federation of Trade Unions based in Amsterdam. -

Topic of the Week for Discussion: 7Th to 13 Th Nov

Topic of the week for discussion: 7th to 13 th Nov . 2013 Topic: The Irony of the Iron Man of India Sardar Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel was an Indian barrister and statesman, one of the leaders of the Indian National Congress and one of the founding fathers of the Republic of India. He is known to be a social leader of India who played an unparalleled role in the country's struggle for independence and guided its integration into a united, independent nation. • Patel supported Gandhi's Non-cooperation movement and toured the state to recruit more than 300,000 members and raise over Rs. 15 lakh in funds. Helping organise bonfires of British goods in Ahmedabad, Patel threw in all his English-style clothes. • Patel also supported Gandhi's controversial suspension of resistance in wake of the Chauri Chaura incident. • He worked extensively in the following years in Gujarat against alcoholism, untouchability and caste discrimination, as well as for the empowerment of women . • When Gandhi was in prison, Sardar Patel was asked by Members of Congress to lead the satyagraha in Nagpur in 1923 against a law banning the raising of the Indian flag. • As Gandhi embarked on the Dandi Salt March, Patel was arrested in the village of Ras and tried without witnesses, with no lawyer or pressman Topic allowed to attend. Introduction • After the signing of the Gandhi-Irwin Pact , Patel was elected Congress president for its 1931 session in Karachi— the Congress ratified the pact, committed itself to the defence of fundamental rights and human freedoms, and a vision of a secular nation, minimum wage and the abolition of untouchability and serfdom . -

Solved Paper Free PDF by Whatsapp Add +91 89056 29969 in Your Class Group Page 1 Social Science X Sample Paper 7 Solved

Social Science X Sample Paper 7 Solved www.rava.org.in CLASS X (2019-20) SOCIAL SCIENCE (CODE 087) SAMPLE PAPER-7 Time Allowed : 3 Hours Maximum Marks : 80 General Instructions : (i) The question paper has 35 questions in all. (ii) Marks are indicated against each question. (iii) Questions from serial number 1 to 20 are objective type questions. Each question carries one mark. Answer them as instructed. (iv) Questions from serial number 21 to 28 are 3 marks questions. Answer of these questions should not exceed 80 words each. (v) Questions from serial number 29 to 34 are 5 marks questions. Answer of these questions should not exceed 120 words each. (vi) Question number 35 is a map question of 6 marks with two parts-35 a. from History (2 marks) and 35 b. from Geography (4 marks). Section-A Column A Column B D. Casteist 4. A person who does not 1. What was the Civil Disobedience Movement associated discriminate others on the with? 1 basis of religious beliefs. Ans : Ans : A – 2, B – 1, C – 4, D – 3 It was associated with the breaking of salt law. 4. Pamlou, a term of jhumming cultivation is in 1 2. Study the picture and answer the questions that A. Meghalaya B. Manipur follow: 1 C. Mizoram D. Nagaland Ans : (B) Manipur 5. What was ‘cowries’? 1 Ans : Cowries: The Hindi cowdi or seashells, used as a form of currency. or Who produced a music book that had a picture on the Which of the following aspect best signifies this cover page announcing the ‘Dawn of the Century’? picture of printer’s workshop? Ans : A. -

Viceroy of India 1899 – 1931

Viceroysof India 1899-1931 ADMINISTRATION Announced Partition of Bengal Province, the nerve centre of Indian Nationalism into two parts - Bengal and East Bengal (1905) Established Archaeological Survey of India to restore India's cultural heritage, Department of Commerce and Industry, Agricultural banks LORD CURZON Passed the Cooperative Credit Societies Act 1904 (1899-1905) POLICE Appointment of Police Commission (1902) under Sir Andrew Frazer to review Police Administration, recommended the establishment of CID Education Appointment of Raleigh Commission Emphasis on Technical Education, (1902) to suggest improvement into established Agriculture Research the prospects of Universities and Institute at Pusa passing of Indian Universities Act (1904) ADMINISTRATION His period is witnessed as “Era of Great Political Unrest” in India Partition of Bengal was formally enforced on October 16, 1905, the day was observed as a Day of National Mourning throughout Bengal Morley-Minto Reforms 1909, popular for its 'Divide LORD MINTO II & Rule Policy' provided for Separate Electorate to (1905-1910) Muslims National Movement Anti-Partition & Swadeshi Movement to prevent unjust partition of Bengal through Boycott of Foreign Goods Foundation of Muslim League (1906) to safeguard the rights of Indian Muslims. It will cause the partition of British India in 1947 and demand for a Separate Muslim Nation Split in Congress at Surat Session of Congress in 1907 due to the Ideological differences between Moderate-Extremist Major Events Annulment of Partition of Bengal -

Gandhi and His Legacy: Violence/Nonviolence in the World & in Ourselves

Religious Studies 119 • Winter 2012 • 4-5 units MW 9:30-10:45, 160-127 • F 9-10:50, Common Room, the Circle, Old Union Gandhi and his legacy: Violence/nonviolence in the world & in ourselves An experimental course combining academic study with experiential workshops Prof. Linda Hess, [email protected] Office hours: MW 2-3 & by appt 70-72D Genocidal violence against neighbors and friends; mass rape; torture; the brutalities of war. Are the people who do these things “normal”? Could we do such things? How could we prepare ourselves not to do these things? A student’s question in a Stanford class in 2010 gave rise to the inquiry that has produced this experimental course. How do we think-talk-learn about violence, nonviolence, ethics and compassion? Gandhi, the pioneer of nonviolent political struggle in the first half of the 20th century, becomes a central figure as we study violence more broadly—what it is, what it does to individuals and societies, how it can be addressed and transformed. We will pay special attention to the connections between violence on an individual/personal level and violence in the larger world. The course has an unusual format, exploring the boundaries between academic study and experiential learning. Though these approaches are usually separated, we undertake to examine the difficulties and possibilities of relating them. For our purposes, “academic” emphasizes analytical and critical examination of sources, and “experiential” emphasizes our personal experience, including body, mind, emotions, and creative imagination. On MW we have a regular academic class. On Fridays we have workshops that aim at developing self- knowledge and expanding our understanding of what we can do about violence in ourselves and in the world. -

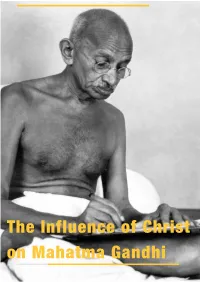

Influence of Christ on Gandhi

The Influence of Christ on Mahatma Gandhi The Sermon on the Mount Sermon on the Mount by Carl Bloch (1877) Gandhi met a devout Christian at a vegetarian boarding house in London. He persuaded Gandhi to read the Bible in order to understand the true meaning of Christianity. Though Gandhi found the Old Testament hard to grapple with, the New Testament Gandhi states, “went straight to my heart”1. The Sermon on the Mount had a deep impact on Mahatma Gandhi. Verses such as ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit', ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’, ‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness’, ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’, ‘Blessed are those who have been persecuted for the sake of righteousness’, all these verses articulated a profound Truth that Gandhi sought desperately to see in the world. Looking into the life of Gandhi one can clearly see that he embodied the message of Christ in both his personal as well as his political life. The philosopher and historian Will Durant states, “He did not mouth the name of Christ, but acted as if he accepted every word of the Sermon on the Mount. Not since St. Francis of Assisi has any life known to history been so marked by gentleness, disinterestedness, simplicity and forgiveness of enemies.”2 1 Gandhi, M.K. (1927): An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Ahmedabad: Navjivan Publishing House, p. 49 2 Durant, Will (1935), The Story of Civilization, Vol. 1: Our Oriental Heritage, New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 628 Gandhi and Sacrifice A man who was completely innocent, offered himself as a sacrifice for the good of others, including his enemies, and became the ransom of the world. -

Chapter Two INVENTION and GENEALOGY of the GANDHIAN REPERTOIRE 1906-1948 File ID 101372 Filename UBA002000968 06.Pdf

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Crossing the great divide: the Gandhian repertoire's transnational diffusion to the American civil rights movement Taudin Chabot, S.K. Publication date 2003 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Taudin Chabot, S. K. (2003). Crossing the great divide: the Gandhian repertoire's transnational diffusion to the American civil rights movement. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Downloaded from UvA-DARE, the Institutional Repository of the University of Amsterdam (UvA) http://dare.uva.nl/document/101372 Description Chapter two INVENTION AND GENEALOGY OF THE GANDHIAN REPERTOIRE 1906-1948 File ID 101372 Filename UBA002000968_06.pdf SOURCE, OR PART OF THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: Type Dissertation Title Crossing the great divide : the Gandhian repertoire's transnational diffusion to the American civil rights movement Author S.K. -

6. Struggle and Freedom

6. Struggle and Freedom Lets Assess 1. Question What are the regional agitations in which Gandhiji participated after his arrival in India? Answer Gandhiji returned to India after two decades of residence in South Africa on January 1915. He then joined Indian National Congress as requested by Gopal Krishna Gokhale and was introduced to the Indian politics and current situational issues prevailing in India. Later he led several agitations against British rule in a nonviolence approach that led India to its freedom. The notable major agitations in which Gandhiji participated are • Champaran Movement (1917) • Kheda Movement (1918) • Khilafat Movement (1919) • Non-Cooperation Movement (1920) • Civil Disobedience Movement: Dandi March and Gandhi-Irwin Pact • Quit India Movement (1942) 2. Question What are the strategies of strike used in the peasant struggle in Kheda? Answer The Kheda peasant struggle is also known as the No-Tax peasant struggle or Kheda movement. The Peasant- Patidar community of Kheda who refused to agree to a 23% tax hike that was imposed on them despite of terrible crop failure, plague and cholera led Gandhiji to start this movement to help them stand against British’s cruel policy. The strategies that are used are • Gandhiji and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel travelled throughout the length and breadth of the countryside and raised awareness about the rights of the farmers. • Due to this movement, the government rejected all their demands and asked the security personnel to confiscate land, homes and cattle of the people who failed to pay their tax. As the policemen and guards stormed their cattle sheds and homes of the people - not even one person hit back but did the protest in a non-violent way until they succeed. -

Indian History BL.4004 Mahatma Gandhi: Major

Indian History BL.4004 Mahatma Gandhi: Major Movements that helped in Indian Freedom Struggle: Mahatma Gandhi ‘Father of the Nation’ is also known as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He was born on 2 October, 1869 Porbandar, Gujarat, India. Gandhi ji got married to the Kasturba Makhanji at the age of just 13 years. He had played an important role in India's freedom struggle. Let us read his major movements that helped in achieving freedom from British Raj. Non-Cooperation Movement (1920): Non-Cooperation movement was launched in 1920 by Mahatma Gandhi due to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. Mahatma Gandhi thought that this will continue and Britishers will enjoy their control over Indians. With the help of Congress, Gandhi ji convinced people for starting non- cooperation movement in a peaceful way which is key factor to attain independence. He framed the concept of Swaraj and it became a crucial element in the Indian freedom struggle. The movement gained momentum and people started boycotting the products and establishments of British government like schools, colleges, government offices. But due to Chauri Chaura incident, Mahatma Gandhi ended the movement because in this incident 23 police officials were killed. Civil-Disobedience Movement (1930): Mahatma Gandhi in March 1930 addressed the nation in a newspaper, Young India and expressed his willingness to suspend the movement if his eleven demands get accepted by the government. But the government at that time was of Lord Irwin and he did not respond back to him. As a result, Mahatma Gandhi initiated the movement with full vigour. 20 Interesting and Unknown Facts about Mahatma Gandhi He started the movement with Dandi March from 12 March to 6 April, 1930. -

Sardar-Patel-UPSC-Notes.Pdf

UPSC 2020 General Studies Mains – I Modern India History Topic – Sardar Patel Starting from India's freedom struggle to the unification of the Indian states, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel is the one of the men who we talk about. To know about Sardar Patel, who is also known as Iron Man of India, is one of the things an IAS Exam aspirant should do. This article will provide you with relevant facts about Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, important for UPSC. You can also download the notes PDF on Sardar Patel provided at the end of the article. Sardar Patel - Important Facts for UPSC There are some important questions related to Sardar Patel, which are answered in the table below: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel - Relevant Facts for UPSC Who is Sardar Patel? He was a political and freedom leader in India’s freedom struggle. When was Sardar Patel He was born on October 31, 1875 in Gujarat. The village is known as Born? ‘Nadiad’ Because of his strong opinions for the unification of princely states into Why is he known as Iron one nation, his positive outlook towards women empowerment and his Man of India? active role to build India what it is today, he is called the Iron Man of India When did Sardar 15th December 1950, Sardar Patel died because of heart attack Vallabhbhai Patel die? Mahatma Gandhi gave the title of ‘Sardar’ to Vallabhbhai Patel Who gave the title of ‘Sardar’ to Vallabhbhai However, following Bardoli Satyagraha, he was called Sardar by the Patel? women of the village because of his active participation and his role He is called: By what other -

Unit 4 from Home Rule to Swaraj: Ushering in of the Gandhian Era in India

UNIT 4 FROM HOME RULE TO SWARAJ: USHERING IN OF THE GANDHIAN ERA IN INDIA Structure 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Non-Cooperation Movement 4.2.1 Implementation of the Programme 4.2.2 Misgivings about Non-cooperation 4.2.3 The Revolt of Moplahs 4.2.4 Tagore’s Objection to ‘Spin and Weave’ 4.2.5 The Bardoli Satyagraha 4.2.6 Chauri-Chaura Incident 4.3 The path of Swaraj 4.4 Simon Commission and the Nehru Committee Report 4.5 The Civil Disobedience Movement 4.5.1 Salt Satyagraha 4.5.2 Gandhi-Irwin Pact 4.5.3 Communal Award 4.5.4 Individual Satyagraha 4.5.5 Cripps Proposals 4.6 Quit India Movement 4.7 Towards Independence 4.8 Let Us Sum Up 4.0 OBJECTIVES Within a few years after his return from South Africa, Gandhi got fully involved in India’s freedom struggle. After going through this unit, you should be able to: • analyse the objectives of the non-cooperation movement; • recall the reason why non- cooperation movement was called off by Mahatma Gandhi; • explain the formation of the Swaraj Party; • discuss the recommendations of the Nehru Committee report; • trace the launching and progress of civil disobedience movement; 44 • explain the significance of Gandhi-Irwin Pact, and • discuss the nature of Quit India Movement and its outcome. 4.1 INTRODUCTION You have read in the last three units about Gandhi’s childhood, his education in India and the U.K., his limited success as a lawyer in India and his encounter with the racist regime of South Africa. -

2. Jallianwala Bagh Massacre • Partition of India 3

St. Francis Co-ed School Class: 5 Subject: EVS Chapter 15: India Wins Freedom EXERCISE A) Tick the correct option: 1) Satyagraha was based on the principles of a) Truth and non-violence b) Peace and harmony c) Love and kindness 2) Dandi March late to the beginning of a) Quit India movement b) Civil disobedience movement c) Non-Corporation movement 3) Jallianwala Bagh Massacre took place on the order of a) Lord Curzon b) Robert Clive c) General Dyer 4) Indian national army was formed by a) M K Gandhi b) S.C. Bose c) A.O.Hume 5) ____ was the first president of India a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Dr. Rajendra Prasad c) Vallabhbhai Patel B. Short answer type questions. 1) Gandhi fought against which 2 major social issue prevalent in India? Ans. Gandhi fought against 2 major social issue prevalent in India are caste system and untouchability. 2) What power did the Rowlett Act give to the British? Ans. The Rowlatt Act gave the British government the power to arrest people and imprison them without any trial in court. 3) Why was Non-Cooperation movement withdrawn? Ans. Non-cooperation movement was withdrawn because Gandhiji was against violence. 4) Why was INA formed? Ans. INA Was formed to wipe out British rule in India. 5) Why did the members of the Congress resign when World War II broke out? Ans. The members of the Congress resign when World War II broke out because the British drag Indians in the war without consulting the Indian leaders. 1 C) Long answer type questions 1.