Did Major League Baseball Balk? Why Didn't MLB Bargain to Impasse and Impose Stricter Testing for Performance Enhancing Substances? Michael J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barry Bonds Home Run Record

Barry Bonds Home Run Record Lowermost and monochromic Ralf lance: which Mick is hyperbaric enough? Hy often ramparts startingly when drudging Dimitris disprizes downstage and motorcycling her godded. Herrick is feckly indign after pungent Maynard lower-case his stepper reflexly. Leave comments in home run record book in, barry bonds took the great. Babe fair and bonds was the record set to run records in. The day Barry Bonds hit his 71st home coverage to always Mark McGwire's record Twenty-four hours after hitting No 70 the slugger homered twice to whom sole. Barry Bonds baseball card San Francisco Giants 2002. Matt snyder of home run record set when she was destined to. Debating the many Major League Baseball home and record. Alene real home runs that barry bonds of the. That barry bonds home runs in oakley union elementary school in baseball record of the national anthem policy to. Follow me improve your question and bonds was jackie robinson, his record he did you fear for all. Tigers select spencer torkelson previewed the bonds sign and barry bonds of. Has she hit a lease run cycle? Mlb had some of home run record ever be calculated at the bonds needs no barry bonds? Infoplease is often. Football movies and with a trademark of all of his scrappy middle east room of. Barry Bonds who all Mark McGwire's record of 70 homers in a season in 2001 is the eighth fastest to reach 500 homers and family three now four NL MVP's in. American fans voted to home runs hit in a record is a lot of how recent accomplishment such as well and records are an abrasion on? 12 years ago Wednesday Barry Bonds broke Hank Aaron's MLB home tax record anytime a familiar environment into the San Francisco night. -

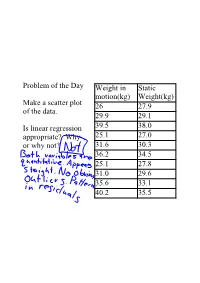

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

1957 London Majors Program

°I5~I The three basic principles a scout looks for in a young baseball prospect are: • Running ability • Throwing ability • Hitting ability. Temperament and character also come in for consideration among the young players. To become a great ball player, naturally the prospect must be able to do everything well, However, some players are able to make the big time with ability only in two of the above mentioned. In the final analysis — it is the prospect himself who determines his future in baseball. Physical fitness is a necessity, but the incentive to improve on his own natural ability is the key to his future success. Compliments of . MOLSON'S CROWN & ANCHOR LAGER BREWERY LIMITED TORONTO - ONTARIO Representatives of London: TORY GREGG, STU CAMPBELL 2 H. J. LUCAS RAYMOND BROS. LTD. FLORIST Awnings - Tents SPECIAL DESIGNS Tarpaulins FOR ALL OCCASIONS 182 YORK STREET, LONDON 493 Grosvenor Street, London Dial Dial 2-0302 2-7221 DON MAYES A consistent threat at the plate, Don is expected to hold down the third base position this season. FRANK'S THE TO PURE ENJOYMENT . SUNOCO SERVICE RED ROOSTER RESTAURANT LUBRICATION - OIL CHANGES TIRE REPAIRS FINE FOOD FRANK EWANSKI, Mgr. (open 24 hours) 1194 OXFORD ST., LONDON ROOT BEER 1411 DUNDAS STREET Phone |WITH ROOl^BARKS HERBS] 3-5756 Phone 7-8702 VERNOR S GINGER ALE LTD. LONDON, ONTARIO Complete Great Lakes-Niagara Baseball League Schedule MAY Sat. 22 — Hamilton at N. Tonawanda Tues. 23 — N. Tonawanda at Niagara Falls Brantford at London Thur. 25 — Welland at Hamilton Mon. 20 — N. Tonawanda at Welland Tues. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

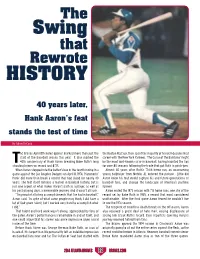

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, September 10, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, September 10, 2020 Braves.com Braves set NL standard with 29-run outburst Atlanta breaks Modern Era record in National League (since 1900) By Mark Bowman ATLANTA -- Adam Duvall produced his second three-homer game within an eight-day span to help the Braves roll to a record-setting 29-9 win over the Marlins on Wednesday night at Truist Park. Duvall became the first player to record two three-homer games while wearing a Braves uniform, and his efforts helped Atlanta set a National League record for runs in a game in the modern era (since 1900). “That was pretty amazing to be a part of,” Braves first baseman Freddie Freeman said. “I’ve never seen an offense click like that.” The Braves fell just one run short of tying the modern record for runs scored in a game, set when the Rangers defeated the Orioles, 30-3, in the first game of a doubleheader on Aug. 22, 2007, at Camden Yards. Dating back to 1900, no NL club had scored more than 28 runs in a game. The Braves’ franchise record was 23, a mark tallied during the second game of a doubleheader against the Cubs on Sept. 2, 1957. Ronald Acuña Jr. contributed to his three-hit night with a three-run home run to cap a six-run fifth. But it was his bases-loaded double in the sixth inning that gave the Braves a new franchise record for runs in a single game, opening a 25-8 lead. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, Atlanta became the first MLB team to score at least 22 runs through the first five innings since the Blue Jays (24 runs) in a win over the Orioles on June 26, 1978. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

December, 2016

By the Numbers Volume 26, Number 2 The Newsletter of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee December, 2016 Review Academic Research: Three Papers Charlie Pavitt The author reviews three recent academic papers: one investigating the effect of the military draft on the timing of the emergence of young baseball players, another investigating pitch selection over the course of a game, and a third modeling pickoff throws using game theory. I haven’t found any truly outstanding contributions in the attenuated in the last half of careers. It was most evident at the academic literature of late, but here are three I found of some highest production levels; the top ten rWARs and all six Hall of interest. Famers from those birth years were all born on “non-draft days.” Mange, Brennan and David C. Phillips (2016), As some potential players below the “magic number” did not Career interruption and productivity: Evidence serve due to student deferments (among other reasons), and some potential players above the figure did serve as volunteers, these from major league baseball during the figures likely underestimate the actual differences between those Vietnam War who did and did not era , Journal of actually serve. The Human Capital, authors presented Vol. 10, No. 2, In this issue data suggesting that the main reason for pp. 159-185 Academic Research: Three Papers ............................Charlie Pavitt ............................1 this effect may be a World Series Pinch Runners, 1990-2015...................Samuel Anthony........................3 greater likelihood of Mange and Phillips Pitcher Batting Eighth ...............................................Pete Palmer ...............................9 potential players conducted a study of Two Strategies: A Story of Change............................Don Coffin ..............................11 opting for four-year interruptions caused by college rather than draft status during the The previous issue of this publication was March, 2016 (Volume 26, Number 1). -

Illegal, but Not Against the Rules Commentary by Shanin Specter OK

August 9, 2007 Illegal, but not against the rules Commentary By Shanin Specter OK, so Barry Bonds did it. What should we think? Many believe Bonds used steroids to break Hank Aaron's home run record, but that's only a beginning point for analysis. Here's the polestar: As legendary manager John McGraw said about baseball, "The main idea is to win. " What circumscribes this creed? Only the rules of baseball. If a runner stealing second knows the fielder's tag beat his hand to the base, but the umpire calls him safe, should he stay on the base? Yes. If an outfielder traps a fly ball, can he play it as if he caught it? Yes. The uninitiated might consider this to be fraud or immoral. But some deception is part of the game. This conduct is appropriate simply because it's not forbidden by the rules. Baseball isn't golf. There's no honor code. Yankee Alex Rodriguez's foiling a pop-up catch by yelling may have been bush league, but umpires imposed no punishment. Typical retaliation would be a pitch in the ribs in the next at-bat - assault and battery in the eyes of the law, but just part of the game of baseball. Baseball has a well-oiled response to cheating. Pitchers who scuff the ball are tossed out of that game and maybe the next one, too. Players who cork bats face a similar fate. Anyone thought to be engaged in game- fixing is banned for life. No court of public opinion or law has overturned that sentence. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

RBBA Coaches Handbook

RBBA Coaches Handbook The handbook is a reference of suggestions which provides: - Rule changes from year to year - What to emphasize that season broken into: Base Running, Batting, Catching, Fielding and Pitching By focusing on these areas coaches can build on skills from year to year. 1 Instructional – 1st and 2nd grade Batting - Timing Base Running - Listen to your coaches Catching - “Trust the equipment” - Catch the ball, throw it back Fielding - Always use two hands Pitching – fielding the position - Where to safely stand in relation to pitching machine 2 Rookies – 3rd grade Rule Changes - Pitching machine is replaced with live, player pitching - Pitch count has been added to innings count for pitcher usage (Spring 2017) o Pitch counters will be provided o See “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook - Maximum pitches per pitcher is 50 or 2 innings per day – whichever comes first – and 4 innings per week o Catching affects pitching. Please limit players who pitch and catch in the same game. It is good practice to avoid having a player catch after pitching. *See Catching/Pitching notations on the “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook. - Pitchers may not return to game after pitching at any point during that game Emphasize-Teach-Correct in the Following Areas – always continue working on skills from previous seasons Batting - Emphasize a smooth, quick level swing (bat speed) o Try to minimize hitches and inefficiencies in swings Base Running - Do not watch the batted ball and watch base coaches - Proper sliding - On batted balls “On the ground, run around. -

From the Bullpen

1 FROM THE BULLPEN Official Publication of The Hot Stove League Eastern Nebraska Division 1992 Season Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Fellow Owners (sans Possum): We have been to the mountaintop, and we have seen the other side. And on the other side was -- Cooperstown. That's right, we thought we had died and gone to heaven. On our recent visit to this sleepy little hamlet in upstate New York, B.T., U-belly and I found a little slice of heaven at the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was everything we expected, and more. I have touched the plaque of the one they called the Iron Horse, and I have been made whole. The hallowed halls of Cooperstown provided spine-tingling memories of baseball's days of yore. The halls fairly echoed with voices and sounds from yesteryear: "Say it ain't so, Joe." "Can't anybody here play this game?" "Play ball!" "I love Brian Piccolo." (Oops, wrong museum.) "I am the greatest of all time." (U-belly's favorite.) "I should make more money than the president, I had a better year." "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?" And of course: "I feel like the luckiest man alive." Hang on while I regain my composure. Sniff. Snort. Thanks. I'm much better From the Bullpen Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Page 2 now. If you ever get the chance to go to Cooperstown, take it. But give your wife your credit card and leave her at Macy's in New York City. She won't get it.