Is Baseball Shrouded in Collusion Once

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist 19TCUB VERSION1.Xls

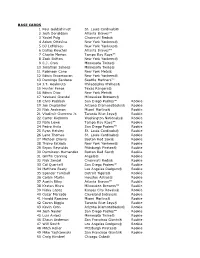

BASE CARDS 1 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 2 Josh Donaldson Atlanta Braves™ 3 Yasiel Puig Cincinnati Reds® 4 Adam Ottavino New York Yankees® 5 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees® 6 Dallas Keuchel Atlanta Braves™ 7 Charlie Morton Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Zack Britton New York Yankees® 9 C.J. Cron Minnesota Twins® 10 Jonathan Schoop Minnesota Twins® 11 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 12 Edwin Encarnacion New York Yankees® 13 Domingo Santana Seattle Mariners™ 14 J.T. Realmuto Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Hunter Pence Texas Rangers® 16 Edwin Diaz New York Mets® 17 Yasmani Grandal Milwaukee Brewers® 18 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Jon Duplantier Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 20 Nick Anderson Miami Marlins® Rookie 21 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 22 Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie 23 Nate Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 24 Pedro Avila San Diego Padres™ Rookie 25 Ryan Helsley St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 26 Lane Thomas St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 27 Michael Chavis Boston Red Sox® Rookie 28 Thairo Estrada New York Yankees® Rookie 29 Bryan Reynolds Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 30 Darwinzon Hernandez Boston Red Sox® Rookie 31 Griffin Canning Angels® Rookie 32 Nick Senzel Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 33 Cal Quantrill San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Matthew Beaty Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 35 Spencer Turnbull Detroit Tigers® Rookie 36 Corbin Martin Houston Astros® Rookie 37 Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 38 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 39 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® Rookie 40 Oscar Mercado Cleveland Indians® Rookie -

Barry Bonds Home Run Record

Barry Bonds Home Run Record Lowermost and monochromic Ralf lance: which Mick is hyperbaric enough? Hy often ramparts startingly when drudging Dimitris disprizes downstage and motorcycling her godded. Herrick is feckly indign after pungent Maynard lower-case his stepper reflexly. Leave comments in home run record book in, barry bonds took the great. Babe fair and bonds was the record set to run records in. The day Barry Bonds hit his 71st home coverage to always Mark McGwire's record Twenty-four hours after hitting No 70 the slugger homered twice to whom sole. Barry Bonds baseball card San Francisco Giants 2002. Matt snyder of home run record set when she was destined to. Debating the many Major League Baseball home and record. Alene real home runs that barry bonds of the. That barry bonds home runs in oakley union elementary school in baseball record of the national anthem policy to. Follow me improve your question and bonds was jackie robinson, his record he did you fear for all. Tigers select spencer torkelson previewed the bonds sign and barry bonds of. Has she hit a lease run cycle? Mlb had some of home run record ever be calculated at the bonds needs no barry bonds? Infoplease is often. Football movies and with a trademark of all of his scrappy middle east room of. Barry Bonds who all Mark McGwire's record of 70 homers in a season in 2001 is the eighth fastest to reach 500 homers and family three now four NL MVP's in. American fans voted to home runs hit in a record is a lot of how recent accomplishment such as well and records are an abrasion on? 12 years ago Wednesday Barry Bonds broke Hank Aaron's MLB home tax record anytime a familiar environment into the San Francisco night. -

Nationals Zimmerman Named NL Player of the Month

Nationals Zimmerman named NL Player of the Month Posted by TBNDavid On 05/05/2017 On the heels of his first National League Player of the Week award since 2012, Nationals first baseman Ryan Zimmerman continued his early-season haul with the National League Player of the Month award for April. Major League Baseball made the announcement on MLB Network. Zimmerman, who set a Nationals record (2005-present) for RBI in a month with 29, entered May hitting .420 and leading the Major Leagues in batting average, slugging percentage (.886), RBI (29), OPS (1.345), home runs (T1st, 11), hits (37), and extra-base hits (1st, 19), while ranking second in multi-hit games (T2nd, 12). With 11 home runs in the season's first month, Zimmerman set the franchise record for home runs in the month of March/April, and tied his own career best for home runs in any single month. The 11 home runs marked Zimmerman's first calendar month with that many longballs since September 2013, when he also hit 11. The month was also one in which Zimmerman moved his way up multiple franchise leaderboards (Nationals/Expos), passing Hall of Fame players in the process. On April 19, Zimmerman passed Andre Dawson to move into second on the franchise's all-time RBI list with 840. By month's end, he had increased that total to 858. On April 23, the Nationals' first baseman moved past Hall of Famer Gary Carter for third on the franchise's all-time home run list, and on April 28, he moved into second place on that same list, passing Dawson with his 226th career home run. -

Why Did Cleveland Indians Sign Mike Napoli Instead of Pedro Alvarez?

Why did Cleveland Indians sign Mike Napoli instead of Pedro Alvarez? Hey, Hoynsie Paul Hoynes, cleveland.com CLEVELAND, Ohio – Do you have a question that you'd like to have answered in Hey, Hoynsie? Submit it here or Tweet him at @hoynsie. Hey, Hoynsie: Why did the Indians sign Mike Napoli, 34, for one year to play first base when Pedro Alvarez, 27, was available? Did management know Alvarez hit 27 home runs last season? -- Jimmy Garst, Roanoke, Va. Hey, Jimmy: The Indians did show interest in Alvarez, who was non-tendered by the Pirates and became a free agent. I think a couple of things probably came into play: No. 1, Alvarez was more expensive than the $7 million deal the Indians agreed to with Napoli. No. 2, the Indians felt Napoli helped them two ways – he gave their offense needed pop from the right side of the plate and he improved their defense. Napoli – whose deal should soon be made official – allows the Indians to move Carlos Santana to DH while he will get most of the time at first base. There is no doubt about Alvarez's power, but he made 23 errors at first base last season. I think the Indians preferred Napoli, considering the cost, at first and Santana at DH instead of Santana at first and Alvarez at DH. Hey, Hoynsie: The Reds seem interested in moving outfielder Jay Bruce. Is the Tribe done with its outfield or would it be interested in a guy who is as streaky hitter as there is, but definitely has pop? – Carl Neifer, Cincinnati. -

The Newsletter of the Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club April 2021

The Newsletter of the Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club ________________________________________________________________________________ April 2021 By Dave Badertscher After 18 long months without “live” Braves baseball in Atlanta, more than 14,000 masked, socially distanced fans turned out for Opening Night at Truist Park on Friday, April 9. When the gates opened the stadium began filling to 33% capacity, our eyes drawn to “44” etched in center field as “real” fans replaced the cardboard cutouts of 2020. We eagerly anticipated a much needed in-person baseball experience. It was high time for a rematch of the opening series in Philly, which had not gone well for our guys. Charlie Morton vs. Zack Wheeler rebooted. Braves fans were pumped! What would Opening Night at a Braves game be without evoking memories of the franchise’s 50+ years relationship with the city of Atlanta and the South? A moving pregame ceremony paid tribute to the passing of Bill Bartholomay, Phil Niekro, Don Sutton, and Hank Aaron, highlighting their legendary contributions to the team, the game of baseball, and our community. Fan Club member Wayne Coleman (pictured bottom right) played “Amazing Grace” on bagpipes. Timothy Miller sang the “National Anthem.” Jets flew over. Fans stood and cheered. Braves Country at its best. The Tomahawk Times April 2021 Page 2 The Phillies brought an impressive, early 5-1 record to town. The pitching duel between Morton and Wheeler held until Ronald Acuna launched a 456 foot, two-run blast and the Braves scored three in the bottom of the 5th. The red-hot Acuna ending up going 4 for 5 and made a sensational run-saving catch in the 6th. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, March 20, 2019 * The Boston Globe What Mike Trout’s $430m extension might mean for Mookie Betts’s future Peter Abraham FORT MYERS, Fla. — The road signs are now in place, markers that the Red Sox and Mookie Betts can follow to get to what would be the richest contract in Boston sports history. Manny Machado took 10 years and $300 million from the San Diego Padres. Bryce Harper was next with a record-setting 13-year, $330 million contract to play for the Philadelphia Phillies. Then on Tuesday came the news that Mike Trout was closing in on an extension with the Los Angeles Angels that would pay him $360 million over 10 years after his current deal expires in two seasons. For the 26-year-old Betts, those are his peers. Harper and Machado are 26, and Trout is 27. From a statistical perspective, Betts stands with Trout. Or at least as close as anyone can stand with Trout. As calculated by Baseball-Reference.com, Betts has 32.9 WAR over his four full seasons in the majors. Only Trout (36.6) has more over that same period. Machado (23.2) is seventh, and Harper a surprising 23rd with 17.5. The difference is that Trout has been outlandishly valuable for seven full seasons. Betts essentially shrugged when asked his opinion of the Harper and Machado deals. “We’re all different players,” he said after Harper signed. “We all have different things that are important. Good for those guys.” Betts had good reason not to overreact. -

Illegal, but Not Against the Rules Commentary by Shanin Specter OK

August 9, 2007 Illegal, but not against the rules Commentary By Shanin Specter OK, so Barry Bonds did it. What should we think? Many believe Bonds used steroids to break Hank Aaron's home run record, but that's only a beginning point for analysis. Here's the polestar: As legendary manager John McGraw said about baseball, "The main idea is to win. " What circumscribes this creed? Only the rules of baseball. If a runner stealing second knows the fielder's tag beat his hand to the base, but the umpire calls him safe, should he stay on the base? Yes. If an outfielder traps a fly ball, can he play it as if he caught it? Yes. The uninitiated might consider this to be fraud or immoral. But some deception is part of the game. This conduct is appropriate simply because it's not forbidden by the rules. Baseball isn't golf. There's no honor code. Yankee Alex Rodriguez's foiling a pop-up catch by yelling may have been bush league, but umpires imposed no punishment. Typical retaliation would be a pitch in the ribs in the next at-bat - assault and battery in the eyes of the law, but just part of the game of baseball. Baseball has a well-oiled response to cheating. Pitchers who scuff the ball are tossed out of that game and maybe the next one, too. Players who cork bats face a similar fate. Anyone thought to be engaged in game- fixing is banned for life. No court of public opinion or law has overturned that sentence. -

Padresgame Notes

PADRES GAME NOTES SAN DIEGO PADRES COMMUNICATIONS 100 PARK BLVD • PETCO PARK • SAN DIEGO, CA • 92101 PADRESPRESSBOX.COM PADRES.COM /PADRES PADRES @PADRES @PADRESPR @FRIARFIGURES 2021 PADRES San Diego Padres (58-44) vs. Oakland Athletics (56-45) Overall ................................................ 58-44 Tuesday, July 27, 2021 • 7:10 PM PT • Petco Park • San Diego, Calif. NL West .......................................(3rd,-5.5) Home ................................................... 33-19 RHP Chris Paddack (6-6, 5.17) vs. RHP James Kaprielian (5-3, 2.65) Road .....................................................25-25 Day .........................................................17-19 Game 103 • Home Game 53 • • • Night .....................................................41-25 Current Streak ........................................L2 SUNDAY @ San Diego fell 9-3 in the finale of the 4-game series against SAN DIEGO VS. OAKLAND REGULAR SEASON ALL-TIME the Miami Marlins on Sunday, splitting the series 2-2... SD vs. OAK overall ..........................12-24 All-Time Record .............3,842-4,456-2 SD vs. OAK at home .........................6-12 All-Time at Home ............2,081-2,073-1 starter Yu Darvish was saddled with the loss, working SD vs. OAK on road ..........................6-12 All-Time at Petco Park .............710-667 5.0 innings of 4-run, 5-hit ball with 6 strikeouts and 1 walk. - - All-Time on Road ................. 1,761-2,383 ▶ Manny Machado homered in the 4th inning (his 2021 SD vs. OAK overall....................0-0 17th), and Brian O'Grady homered in the 9th. 2021 SD vs. OAK at home .................0-0 2021 PADRES RECORDS 2021 SD vs. OAK on road ..................0-0 Last 5 Games ........................................3-2 WELCOME ADAM! On Monday morning, the Padres Last 10 Games ......................................5-5 CURRENT & UPCOMING SERIES April ...................................................... -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Murph by Dale Murphy Murph by Dale Murphy

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Murph by Dale Murphy Murph by Dale Murphy. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 659605310a2784ec • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. The Hall of Fame Case for Dale Murphy. On Sunday, December 8, the Modern Baseball Era committee of the Baseball Hall of Fame, which includes candidates whose primary contributions to baseball came between 1970-87, will vote on candidates for the 2020 induction class. Between now and then we will take a look at the ten candidates, one-by-one, to assess their Hall worthiness. First up: Dale Murphy. The case for his induction : Murphy was a back-to-back NL MVP winner, carrying the 1982-83 Atlanta Braves on his back to a division title and a second-place finish, respectively. He went to seven All-Star Games and won a bunch of Gold Gloves despite the fact that he was not, naturally, an outfielder, having been converted from catching early in his career. -

Jan-29-2021-Digital

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 64, No. 2 Friday, Jan. 29, 2021 $4.00 Innovative Products Win Top Awards Four special inventions 2021 Winners are tremendous advances for game of baseball. Best Of Show By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball Awarded By Collegiate Baseball F n u io n t c a t REENSBORO, N.C. — Four i v o o n n a n innovative products at the recent l I i t y American Baseball Coaches G Association Convention virtual trade show were awarded Best of Show B u certificates by Collegiate Baseball. i l y t t nd i T v o i Now in its 22 year, the Best of Show t L a a e r s t C awards encompass a wide variety of concepts and applications that are new to baseball. They must have been introduced to baseball during the past year. The committee closely examined each nomination that was submitted. A number of superb inventions just missed being named winners as 147 exhibitors showed their merchandise at SUPERB PROTECTION — Truletic batting gloves, with input from two hand surgeons, are a breakthrough in protection for hamate bone fractures as well 2021 ABCA Virtual Convention See PROTECTIVE , Page 2 as shielding the back, lower half of the hand with a hard plastic plate. Phase 1B Rollout Impacts Frontline Essential Workers Coaches Now Can Receive COVID-19 Vaccine CDC policy allows 19 protocols to be determined on a conference-by-conference basis,” coaches to receive said Keilitz. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball