Examining the Effect of Innovation on the Market Structure of the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

Jazzletter 93023 April 1984 - Vol

P.O. Box 24o Ojai, Calif. Jazzletter 93023 April 1984 - Vol. 3 No. 9» punishment oftheir users. They claim ofcourse to be motivated by The Road to Gadgets a deep and sensitive concern for the well-being of the artists. We The Federal Bureau of Investigation released, early in I984. some shall examine the sincerity ofthis posture. Even the industry‘s own interesting statistics. The number of violent crimes committed in brochures admit that a great deal of taping is done because so the United States in I983 dropped more sharply than at any time manyrecords are difficult or impossible to buy. as a result of the since the organization began keeping figures on them in I960. constant elimination of inventory. The industry has no interest in Serious crimes. including murder, rape, robbery. aggravated substantial and long-lasting music. Often the only way to get assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. were albums containing it is to tape them. In fact. artists end up taping dramatically down. The attorney general‘s office quickly claimed their own out-of-print albums for friends. ‘at some of the decline, which amounted to a respectable seven This brings us to a separate but pertinent subject. \-pBl'C€I"tl, was due to federal law enforcement efforts. But most thoughtful authorities-, including F. Lee Bailey, rejected that explanation for the good reason that these crimes are not federal offenses, and.not subject to FBI prosecution. What then caused Dogs in the Manger ~ the decline? Due to this penchant for fast turnover and maximal profits, the “Demographics play the most important role,” the Washington record companies cancel an album the moment sales fall below a Post said in an editorial. -

Accepted Manuscript Version

Research Archive Citation for published version: Kim Akass, and Janet McCabe, ‘HBO and the Aristocracy of Contemporary TV Culture: affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007’, Mise au Point, Vol. 10, 2018. DOI: Link to published article in journal's website Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: This manuscript version is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives License CC BY NC-ND 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact Research & Scholarly Communications at [email protected] 1 HBO and the Aristocracy of TV Culture : affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007 Kim Akass and Janet McCabe In its institutional pledge, as Jeff Bewkes, former-CEO of HBO put it, to ‘produce bold, really distinctive television’ (quoted in LaBarre 90), the premiere US, pay- TV cable company HBO has done more than most to define what ‘original programming’ might mean and look like in the contemporary TV age of international television flow, global media trends and filiations. In this article we will explore how HBO came to legitimatise a contemporary television culture through producing distinct divisions ad infinitum, framed as being rooted outside mainstream commercial television production. In creating incessant divisions in genre, authorship and aesthetics, HBO incorporates artistic norms and principles of evaluation and puts them into circulation as a succession of oppositions— oppositions that we will explore throughout this paper. -

Downloading of Movies, Television Shows and Other Video Programming, Some of Which Charge a Nominal Or No Fee for Access

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2011 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO Commission file number 001-32871 COMCAST CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) PENNSYLVANIA 27-0000798 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) One Comcast Center, Philadelphia, PA 19103-2838 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (215) 286-1700 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market Class A Special Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market 2.0% Exchangeable Subordinated Debentures due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 5.50% Notes due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 6.625% Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange 7.00% Notes due 2055 New York Stock Exchange 8.375% Guaranteed Notes due 2013 New York Stock Exchange 9.455% Guaranteed Notes due 2022 New York Stock Exchange SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. -

2010 Sequence K–2 DRAFT Knowledge Maps for Science Table

2010 Sequence K–2 DRAFT Knowledge Maps for Science With this file, we are happy to share with you the working draft Knowledge Maps for grades K–2. While the forthcoming CK Science (CKSci) curriculum will not be directly based on these Knowledge Maps, we offer them as guidance to schools seeking to compare the 2010 Core Knowledge Sequence domains to the NGSS expectations and goals. For each topic, the Knowledge Map: • Organizes content from the 2010 Core Knowledge Sequence. • Includes alignment information and rationale for addressing the relevant Next Generation Science Standards. • Articulates common misconceptions to support teachers as they help children overcome obstacles to understanding. • Lists recommended content objectives for student mastery. • Outlines several possible activities and assessment ideas for each domain of study. These maps offer support to educators as they work to bridge any gaps between the 2010 CK Sequence and the Next Gen. Standards. Table of Contents Kindergarten Unit 1: The Human Body: Five Senses ……………………………... (pgs. 2 – 13) Unit 2: Animals and Their Needs ………………………………….. (pgs. 14 – 27) Unit 3: Plants and Farms …………………………………………… (pgs. 28 – 41) Unit 4: Seasons and Weather ………………………………………. (pgs. 42 – 54) Unit 5: Taking Care of the Earth …………………………………... (pgs. 55 – 66) Unit 6: Pushes, Pulls, and an Introduction to Magnets ……………. (pgs. 67 – 79) Unit 7: The Wright Brothers ………………………………………. (pgs. 80 – 87) Grade 1 Unit 1: The Human Body: Body Systems ….…………………….. (pgs. 88 – 101) Unit 2: Introduction to Our Solar System ……………………….. (pgs. 102 – 116) Unit 3: Introduction to Geology ………………………….……... (pgs. 117 – 132) Unit 4: Living Things & Their Environments ……………..…..... (pgs. 133 – 150) Unit 5: Matter and Its Properties ……...……………………….. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

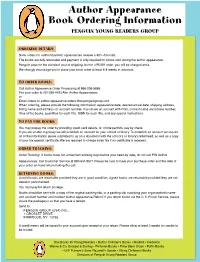

Author Appearance Book Ordering Information PENGUIN Young Readers Group

Author Appearance Book Ordering Information PENGUIN Young READerS Group ORDERING DETAILS: Book orders for author/illustrator appearances receive a 40% discount. The books are fully returnable and payment is only required for books sold during the author appearance. Penguin pays for the standard cost of shipping, but for a RUSH order, you will be charged extra. We strongly encourage you to place your book order at least 6-8 weeks in advance. TO ORDER BOOKS: Call Author Appearance Order Processing at 866-206-5865 Fax your order to 201-256-0013 Attn. Author Appearances or Email orders to [email protected] When ordering, please provide the following information: appearance date, desired arrival date, shipping address, billing name and address (or account number, if you have an account with PGI), contact name and phone number, titles of the books, quantities for each title, ISBN for each title, and any special instructions. TO PAY FOR BOOKS: You may prepay the order by providing credit card details, or, if time permits, pay by check. If you are unable to prepay we will establish an account for your school or library. To establish an account we require all of the information above submitted to us on a document with the school’s or library’s letterhead, as well as a copy of your tax exempt certificate. We are required to charge sales tax if no certificate is received. ORDER TRACKING: Order Tracking: If books have not arrived ten working days before your need-by date, do not call PGI Author Appearances. -

From Dream to Reality

From Dream to Reality 2 0 1 1 A n n u A l R e p o R t M a M a’s Moves into a New Home fter 17 years of leasing operatingA space in our second avenue location downtown, Mama’s Kitchen purchased and renovated a permanent two-story, 11,000 sq. ft. facility at 3960 Our new home boasts: Home avenue. our new doors • An industrial-size commercial opened on august 29, 2011, kitchen, furnished with equipment without interruption of service that will expand food preparation capacity and improve the quality to our clients. Mama’s Kitchen’s and nutritional value of meals. new home creates significant • A more welcoming environment for the hundreds of volunteers who walk opportunities to enhance and through its doors, with appropriate workspaces for staff and volunteers. expand our services to those we • Adequate conference and classroom space to accommodate community meetings, volunteer orientations, trainings and education programs that will serve with increased operational help service recipients, and enable staff, volunteers and community partners efficiency and organizational to stay informed, build skills and share resources. effectiveness. • A pantry, now under the same roof as our kitchen, which will provide perishable items (such as bread, fruits, meats, and dairy items) in addition to nonperishable items. • A convenient location for our volunteer delivery drivers, with easy access to all major San Diego freeways. A Message F r o M o u r b o a r d p r e s i d e n t and executive director As we look back at 2011, we are struck by the amazing spirit of generosity and commitment that so defines the communities of San Diego. -

Stallwood Collection Inventory Books.Numbers !1 of 33! Stallwood Collection Books 19/10/2013 Angell Geo

Stallwood Collection Books 19/10/2013 Aberconway Christabel A Dictionary of Cat Lovers London Michael Joseph 1949 0718100131 Abram David The Spell of the Sensuous New York Vintage Books 1997 0679776397 Acampora Ralph Corporal Compassion: Animal ethics and philosophy of body Pittsburgh, PA University of Pittsburgh Press 2006 822942852 Acciarini Maria Chiara Animali: I loro diritti i nostri 'doveri Roma Nuova Iniziativa Editoriale SpA LibraryThing Achor Amy Blount Animal Rights: A Beginner's Guide Yellow Springs, WriteWare, Inc. 1992 0963186507 OH Achor Amy Blount Animal Rights: A Beginner's Guide Yellow Springs, WriteWare, Inc. 1996 0963186507 OH Ackerman Diane The Zookeeper’s Wife London Old Street Publishing 2008 9781905847464 Adams Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical New York Continuum 1990 0826404553 Theory Adams Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical New York Continuum 1991 0826404553 Theory Adams Carol J., ed. Ecofeminism and the Sacred New York Continuum 1993 0883448408 Adams Carol J. Neither Man Nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals New York Continuum 1994 0826408036 Adams Carol J. Neither Man Nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals New York Continuum 1995 0826408036 Adams Carol J. and Josephine Animals & Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations Durham, NC Duke University Press 1995 0822316676 Donovan, eds. Adams Carol J. and Josephine Beyond Animal Rights: A Feminist Caring Ethic for the New York Continuum 1996 0826412599 Donovan, eds. Treatment of Animals Adams Bluford E Pluribus Barnum: The great showman & the making of the Minneapolis, MN University of Minnesota Press 1997 0816626316 U.S. popular culture Adams Carol J. -

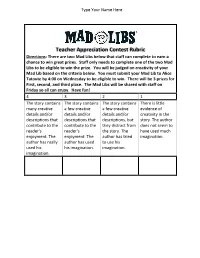

Teacher Appreciation Contest Rubric Directions: There Are Two Mad Libs Below That Staff Can Complete to Earn a Chance to Win Great Prizes

Type Your Name Here Teacher Appreciation Contest Rubric Directions: There are two Mad Libs below that staff can complete to earn a chance to win great prizes. Staff only needs to complete one of the two Mad Libs to be eligible to win the prize. You will be judged on creativity of your Mad Lib based on the criteria below. You must submit your Mad Lib to Alice Tatoute by 4:00 on Wednesday to be eligible to win. There will be 3 prizes for First, second, and third place. The Mad Libs will be shared with staff on Friday so all can enjoy. Have fun! 4 3 2 1 The story contains The story contains The story contains There is little many creative a few creative a few creative evidence of details and/or details and/or details and/or creativity in the descriptions that descriptions that descriptions, but story. The author contribute to the contribute to the they distract from does not seem to reader's reader's the story. The have used much enjoyment. The enjoyment. The author has tried imagination. author has really author has used to use his used his his imagination. imagination. imagination. HOW TO BECOME THE TEACHER’S PET Do you want straight _______________________ ’s on your report LETTER OF THE ALPHABET card? Do you want to bring home comments like “excellent” and “ ________________ ” on all your tests and ________________ ? Follow our ADJECTIVE PLURAL NOUN ________________ -fire guide to becoming the teacher’s ________________ , ADJECTIVE NOUN and you’ll be at the top of the ________________ in no time! NOUN • Tell your teacher every day that she looks ________________ . -

Digitalization and Television Newspictures As Evidence and As Libel

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 9 Number 2 Article 2 3-1-1989 One Technological Step forward and Two Legal Steps Back: Digitalization and Television Newspictures as Evidence and as Libel Don E. Tomlinson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Don E. Tomlinson, One Technological Step forward and Two Legal Steps Back: Digitalization and Television Newspictures as Evidence and as Libel, 9 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 237 (1989). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol9/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ONE TECHNOLOGICAL STEP FORWARD AND TWO LEGAL STEPS BACK: DIGITALIZATION AND TELEVISION NEWSPICTURES AS EVIDENCE AND AS LIBEL* Don E. Tomlinson** I. Introduction ............................................. 237 II. History of Television Newspictures as Admissible Evidence ................................................ 241 III. The Relationship of Television Newspictures to Libel ..... 244 IV. From Analog to Digital: A Revolution in Television Technology .............................................. 249 V. Concerns About and Uses of Digitexed Television Newspictures ............................................ 252 VI. Possible New Life for False Light Privacy Invasion ........ 255 VII. Analysis and Conclusions ................................ 256 I. INTRODUCTION Digitalization, the technological revolution now taking place in tele- vision,' will have a profound impact on the admissibility of television newspictures as evidence,2 and on the status of television newspictures as * Parts of this article appeared in two earlier articles by the author.