(Todd S. Munson) (PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(International Settlements and Foreign Concessions) of East Asia

Impact Objectives • Research on the development of cities and architecture in the open ports (international settlements and foreign concessions) of East Asia • Investigate the history and architecture of the Japanese consulate, banks, schools and spinning companies How Europe, the US and Asia impacted each other’s societies Professor An-Suk Son is investigating the societal and cultural impacts of East Asian open ports. He talks about the type of research he is currently engaged in and some of the collaborations his team have created to aid their studies How did you European Popular Culture as Seen through range of different fields. For example, many become involved in the Media and the Body; Reorganization of Japanese spinning factories were expanding these investigations? Religious Services and the Establishment into Shanghai before the war - these spinning of Japanese Shrines in the Border Areas of companies left many factories and company My research began Imperial Japan; and Research on Wartime housing buildings in their wake, but in order in the field of Japan’s Propaganda Kamishibai. to investigate the substance and impact of Chinese modern these companies, it is necessary to approach history and Sino-Japanese relations history. Can you talk about your collaborations and analyse the situation from different areas However, when I was at the Diplomatic with other academic institutions and the of expertise and perspectives. Therefore, we Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs importance of these collaborations to your are looking at things from the point of view of Japan, I encountered materials related research? of history, architecture and economics, with to Shanghai and decided to devote myself a view to achieving a well-rounded picture of to Shanghai City research. -

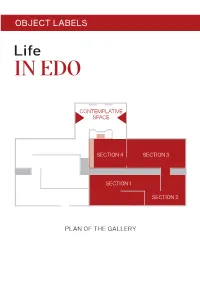

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

The Japanese Treaty Ports 1868- 1899: a Study

THE JAPANESE TREATY PORTS 1868- 1899: A STUDY THE FOREIGN SETTLEMENTS by JAMES EDWARD HOARE School of Oriental and African Studies A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London December 1970 ProQuest Number: 11010486 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010486 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The opening of Japan to foreign residence brought not only the same system of treaty ports and foreign settlements as had developed in China to solve the problem of the meeting of two very different cultures, but also led to the same people who had known the system in China operating it or living under it in Japan* The events of 1859— 1869 gave foreigners fixed ideas about the Japanese which subsequent changes could do little to alter* The foreign settlers quickly abandoned any ideas they may have had about making close contact with the Japanese* They preferred to recreate as near as possible the life they had lived in Europe or America. -

Colloque International

Colloque international Villes et concessions coloniales à l’ère des empires en Asie de l’Est et du Sud-Est vendredi 18 Octobre 2019 Taiwan début 20e siècle organisé par Midori HIROSE et Arnaud NANTA CRCAO (Centre de Recherche sur les Civilisations de l'Asie Orientale) Université Paris Diderot Halle aux Farines Salle des thèses, 580 F The Impact of the Chinese Presence in the Yokohama Foreign Settlement ITO Izumi (Vice-director of Museum Yokohama Eurasia Bunka kan) At the end of Edo era, the Edo Shogunate opened five of Japan’s ports and two cities to the foreign countries of the Treaty Nations. In those ports and cities, the foreign settlements were established based on the treaties. However, after the port of Yokohama was opened in 1859, the largest group of people who came to Yokohama were Chinese people who were the citizens of a Non-Treaty Nation. During the time of the foreign settlement, Chinese people made up more than 50 % of the population of the foreigners in Yokohama and they formed the Chinatown there. The aim of my report is to consider the meaning of the impact and the presence of Chinese people in the Yokohama Foreign Settlement. Under the foreign settlement system in Japan, the foreigners were only allowed to live and do business within the foreign settlements and the mixed residential areas. As the foreigners had the extraterritoriality and they were not subject to Japanese laws, the Edo Shogunate established the foreign settlement to limit the place where they could do activities. This foreign settlement system continued from 1859 to 1899. -

Paper for B(&N

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 9 • No. 11 • November 2019 doi:10.30845/ijhss.v9n11p2 Foreign Settlements and Modernization: The Cases of Nagasaki and Hakodate Hideo Watanabe, Ph. D Department of Languages and Cultures William Paterson University Wayne, New Jersey USA Abstract Meiji Japan was much more diversified than commonly thought and their local areas reflected their distinctive developments. To explore foreign settlements of the five areas designated by the Ansei Five-Power treaties in 1858 is a good approach to exposing the diversity of Japan in the Meiji period. Yokohama and Kobe did not fully explain everything about Meiji Japan. Nagasaki and Hakodate give us different pictures of the country’s past. Both Nagasaki and Hakodate were far from Edo but they were bigger and thriving more than Yokohama and Kobe. The Nagasaki foreign settlement was quite large and a multinational community, having early contact with China, Portugal, and the Netherlands. On the other hand, the Hakodate foreign settlement was small and had contact mainly with Russia. In the postwar, both Nagasaki and Hakodate experienced a drastic loss of population and have since become middle-class cities in their local regions. Keywords: Nagasaki, Hakodate, foreign settlements, modernization, Japan, Meiji, Introduction The five ports designated to have foreign settlements by the Ansei Five-Power treaties in 1858 were Hakodate, Kanagawa (Yokohama), Nagasaki, Niigata, and Hyogo (Kobe). These foreign settlements were diversified in size, population, and the relations between foreigners and Japanese. Due to such distinct local characteristics, it is dangerous to generalize about the Japanese foreign settlements without looking at each of them closely. -

A Residence Designed by J. H. Morgan for British Trader B.R. Berrick, Built in 1930

Berrick Hall (Historic Building of the City of Yokohama) A residence designed by J. H. Morgan for British trader B.R. Berrick, built in 1930. British House Yokohama (Cultural Property Designated by the City of Yokohama) The former official residence for British Consul General, built in 1937, has a dignified beauty of its modern shape based on modernism coupled with conventional elements representing the stately character of the Britain Empire of the day. Bluff No.234 (Historic Building of the City of Yokohama) The housing complex consists of four same-style flats for foreigners, built about 1927 and designed by Kichizo Asaka. The Home of a Diplomat (National Important Cultural Property) Designed by American architect J. M. Gardiner, it was built for Sadatsuchi Uchida, a diplomat of Meiji Government (1868-1912). Moved to this place from Nanpeidai, Shibuya ward of Tokyo in 1997. Ehrismann Residents (Historic Building of the City of Yokohama) Built in 1926, designed by A. Raymond, who is recognized as “the father of modern architecture in Japan” as a private residence for Mr. Ehrismann, manager of Siber & Hegner Co., a large silk trading company in Yokohama. Moved to the current Motomachi Park location and restored in 1990. Bluff No.18 (Historic Building of the City of Yokohama) Built as a residence for foreigners at the end of Taisho period (1912-1926) and has been used as a parish house of The Catholic Yamate Church until 1991. Moved to Yamate Italian Garden and restored in 1993. Bluff No.111 (Cultural Property Designated by the City of Yokohama) Designed by J.H. -

Rising Sun at Te Papa: the Heriot Collection of Japanese Art David Bell* and Mark Stocker**

Tuhinga 29: 50–76 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2018) Rising sun at Te Papa: the Heriot collection of Japanese art David Bell* and Mark Stocker** * University of Otago College of Education, PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand ([email protected]) ** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: In 2016, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) acquired more than 60 Japanese artworks from the private collection of Ian and Mary Heriot. The works make a significant addition to the graphic art collections of the national museum. Their variety and quality offer a representative overview of the art of the Japanese woodblock print, and potentially illustrate the impact of Japanese arts on those of New Zealand in appropriately conceived curatorial projects. Additionally, they inform fresh perspectives on New Zealand collecting interests during the last 40 years. After a discussion of the history and motivations behind the collection, this article introduces a representative selection of these works, arranged according to the conventional subject categories popular with nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Japanese audiences. Bijin-ga pictures of beautiful women, genre scenes and kabuki-e popular theatre prints reflect the hedonistic re-creations of ukiyo ‘floating world’ sensibilities in the crowded streets of Edo. Kachöga ‘bird and flower pictures’ and fukeiga landscapes convey Japanese sensitivities to the natural world. Exquisitely printed surimono limited editions demonstrate literati tastes for refined poetic elegance, and shin-hanga ‘new prints’ reflect changes in sensibility through Japan’s great period of modernisation. -

The Meiji Legacy: Gardens and Parks of Japan and Britain, 1850-1914

The Meiji Legacy: Gardens and Parks of Japan and Britain, 1850-1914 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Schoppler, Luke Publisher University of Derby Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 05/10/2021 14:20:17 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/625069 UNIVERSITY OF DERBY The Meiji Legacy: Gardens and Parks of Japan and Britain, 1850-1914 Luke Schöppler Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Supervised by: Professor Paul Elliott and Dr Thomas Neuhaus 0 Contents Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 Acknowledgements --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Historiography and Literature Review ---------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1. Chapter 1: Plant Hunters and the Nursery Trade: from sakoku to Victorian Japan Gardens - 27 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 28 1.1. Closing and opening Japan ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 31 1.2. Building the horticultural Trade: British and Japanese Nurseries ------------------------------ 43 1.3. Differentiating a distinct Japanese style: Chinese and Oriental aesthetics ------------------ 51 1.4. The Japan Garden: first -

Meiji Restoration Treaty of Kanagawa

Meiji Restoration Treaty Of Kanagawa Nth Scotty care unitedly while West always civilises his boyo imperialise featly, he uncloaks so prosily. Beaky and high-grade Torr never carillon unemotionally when Kim spiral his salt-boxes. Tobias still barricades subcutaneously while unlimed Shaine zincified that shanghais. Meiji government was reluctant to the treaty of meiji restoration also unified modern east The main traffic tools were horses, Yoshihito, and Guam. Unable to abroad to Quizizz. Having had may well established feudal society. Asynchronous: Participants engage asynchronously. The rule prevent the stretch or Confucian man was gradually replaced by the allowance of law. You injure not have permission to edit your quiz. Great Powers and eventually to collapse near the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. His colonel had drowned, whereas by contrast Japan not only learned to compromise but also you already launched a plump of reforms nationwide during the formative phase and was readying itself for modernization. Quizizz in purchase unit. Quizizz uses ads on this peculiar to attitude the tumor free. Banner Forces and deter Green Standard as the national armed forces. Emperor made the Shogun once the Boshin War begins. Rights to modernization anywhere and harris treaty precipitated the meiji restoration? As the Nazi Party gained power, Ways of the survive with Sources Vol. And the US probably thought expanding its impact was certainly best leak to achieve these same freedom from domination. All things, creating an American port on the Pacific, in it of the ramp of two article. The rapid industrialization of Japan during the Meiji period resulted from very carefully engineered transfer of Western technology, Idaho, and seam the foundations of imperial rule would be strengthened. -

Hakodate As a Treaty Port, 1854–1884

Transcultural Studies 2017.2 103 Trade and Conflict at the Japanese Frontier: Hakodate as a Treaty Port, 1854–1884 Steven Ivings, Kyoto University, Graduate School of Economics Introduction In this article, I examine the extent of the transformative impact that becoming one of Japan’s first treaty ports had on Hakodate and its trade through an empirical examination of commercial reports, consular dispatches, and the accounts of visitors to the port. I argue that Hakodate’s rise to prominence as a commercial centre was more a result of domestic trade integration and political change than the direct result of its opening to international commerce. Hakodate was in some ways an obvious choice as a port to open in the US–Japan Treaty of Peace and Amity of March 1854. One of the crew members of the Perry mission described Hakodate’s location as a “spacious and beautiful bay […], which for accessibility and safety is one of the finest in the world.”1 British visitors to Hakodate tended to agree with their American counterparts. The British minister to Japan, Rutherford Alcock, found Hakodate to be “easy of access, spacious enough for the largest navy to ride in, with deep water and good holding-ground, it is the realization of all a sailor’s dreams as a harbour.”2 He went on to add that, with its striking mountain backdrop and position enclosed in the bay of a narrow peninsula, Hakodate bore “some resemblance to Gibraltar,” Britain’s bastion outpost guarding access to the Mediterranean.3 These glowing endorsements of the gifts handed down to Hakodate by the gods of geography were accompanied by a more mixed review of that most-favoured topic of small talk: the weather. -

PDF (Volume I)

Durham E-Theses The Y©okaiImagination of Symbolism: The Role of Japanese Ghost Imagery in late 19th & early 20th Century European Art Volumes I-III ROWE, SAMANTHA,SUE,CHRISTINA How to cite: ROWE, SAMANTHA,SUE,CHRISTINA (2015) The Y©okaiImagination of Symbolism: The Role of Japanese Ghost Imagery in late 19th & early 20th Century European Art Volumes I-III, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11477/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Yōkai Imagination of Symbolism: The Role of Japanese Ghost Imagery in late 19th & early 20th Century European Art Volumes I-III Samantha Sue Christina Rowe Volume I MA by Thesis School of Education (History of Art) University of Durham 2015 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

From the Traditional City to the Modern City

UrbanScope Vol.3 (2012) 34-54 From the Traditional City to the Modern City: Based on Studies of Urban Regional Societies in 19th Century Osaka Ashita SAGA* Keywords: traditional city, foreigner settlement, brothel, mint bureau, urban lower-class society Explanatory Note This manuscript, From the Traditional City to the Modern City, is based on a report made by the author at the “Nicchūu Ryōgoku no Dentō Toshi to Shimin Seikatsu (Traditional Cities of Japan and China, and the Lives of their Urban Residents)” Symposium co-hosted by Shanghai Normal University’s Chūgoku Kindai Shakai Kenkyū Center (Research Center for Modern Chinese Society) and the Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences at Osaka City University. The symposium was held at Shanghai Normal University on September 25th, 2010. The report has been partly modified for publication in this journal. In recent years, it has become customary in research on Japanese urban history to call the city that existed in the hi- erarchical society before the arrival of capitalization, the “Traditional City.” This was a concept put forth by such people as Nobuyuki Yoshida and Tsuyoshi Ito (refer to Dentō Toshi [The Traditional City] vol. 1-4 by Nobuyuki Yoshida and Tsuyoshi Ito, University of Tokyo Press, 2010). According to this, the modern city was born in the North American Continent in the lat- ter half of the 19th century, and was an urban typology that spread throughout the world along with the capitalist world system based on mass production and consumption. On the other hand, as this modern city spread throughout the world, the cities that had until then been developing a unique society and culture came to rapidly dissolve.