Non-Corrigé Uncorrected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2013

Chronicle: The Caucasus In the Year 2013 January 9 January 2013 The Georgian State audit agency launches a probe into the alleged violation of funding political parties’ rules by the United National Movement during the electoral campaign of 2012 11 January 2013 Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulates the head of the Georgian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Ilia II, on his 80th birthday 18 January 2013 During an official visit to Armenia, Georgian Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili promises to the head of the Holy Armenian Apostolic Church Catholicos Karekin II that Armenian history will soon be taught in Georgian schools 19 January 2013 police in Baku clash with shopkeepers protesting a rent increase by the managers of Azerbaijan’s largest shopping center 24 January 2013 The Azerbaijani police break up protests in the town of Ismayilli demanding the resignation of the local governor Nizami Alekberov 26 January 2013 Hundreds of people demonstrate in Baku to express their solidarity with the protests in the town of Ismayilli and some 40 participants are detained by the police including the blogger Emin Milli and investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova 26 January 2013 A statue of Azerbaijan’s late President Heydar Aliyev is removed from a park in Mexico City 27 January 2013 Three activists involved in a 26 January protest in the Azerbaijani capital of Baku are given prison sentences 28 January 2013 The Azerbaijani and Armenian foreign ministers meet in Paris for talks mediated by the OSCE Minsk Group and aimed at settling the conflict -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2014

Chronicle: The Caucasus In the Year 2014 January 1 January 2014 The Georgian State Ministry for Reintegration is renamed into State Ministry for Reconciliation and Civic Equality in a move that Tbilisi officials say will help engagement with the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 4 January 2014 Russia pledges over 180 million dollars to the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2014–2016 through a decree signed by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev with the financial aid to be provided via the Russian Ministry of Construction 14 January 2014 Hungary becomes the twelfth country to recognize Georgia’s neutral travel documents designed for residents of the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 16 January 2014 Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili says that Russia lacks the levers to deter the country’s signing of an Association Agreement with the European Union although provocations are expected 20 January 2014 Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili meets with his Turkish counterpart Abdullah Gül and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during a visit to Turkey that includes meetings with representatives of the Georgian diaspora 30 January 2014 Czech President Milos Zeman says during Armenian President Serzh Sarkisian’s official visit to Prague that the mass killings of Armenians during the Ottoman empire amounted to a “genocide” February 3 February 2014 Azerbaijani parliament speaker Oqtay Asadov calls on religious clerics to perform prayers in Azeri and not in Arabic to make it easier for people to -

Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges

Transcript Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges Dr Maia Panjikidze Minister of Foreign Affairs, Georgia Chair: James Nixey Head, Russia and Eurasia Programme, Chatham House 11 June 2014 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges James Nixey Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. I am absolutely delighted to have Dr Maia Panjikidze here with us in Chatham House. I’ve always said that one thing about Georgia, apart from the fact its politics are always interesting and never dull – you can take that any way you wish – is that the Georgians have always been excellent at sending over their most senior politicians and articulating their point of view on local and wider politics. -

For Ease of Doing Business

Investor.A MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN GEORGIA ge ISSUE 35 OCT.-NOV. 2013 Georgia Is Number The Comeback Kid: Georgian Wine Outperforming Expectations in Russian Market Georgian Ski Resorts Receive A Major Upgrade Why the Georgian Economy May be in Better Shape Than You Realize Impact of Agricultural For Ease Amendment on Investment Of Doing Business Investor.ge OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2013 3 Investor.ge Investor.ge CONTENT AmCham Executive Director 6 Investment in Brief 32 Independence of the Judiciary Amy Denman A brief synopsis of new investments in Georgia: Trends and and business news. Challenges Editor in Chief BGI’s Otar Kakhidze looks at Molly Corso 6 New Millennium Challenge changes and challenges for the Compact to Bridge Work-Skill judiciary in an editorial. Copy Editor Alexander Melin Gap 34 The Direction of Georgia’s Marketing & Promotion 7 The Comeback Kid: Georgian EU Policy: What November’s Sophia Chakvetadze Wine Outperforming Eastern Partnership Summit Expectations in Russian Means for Georgia Promotional Design Market Levan Baratashvili 37 New Restrictions on Foreigner 8 ISET: The future of Georgia’s Ownership of Agricultural Magazine Design and Layout and hospitality industry Land Negatively Impacting Giorgi Megrelishvili An analysis of the tourism Investors Writers sector based on the tourism and Eva Anderson, Emil Avdaliani, Molly hospitality industry chapter in the 39 Georgia’s Per-Diem and Corso, Maia Edilashvili, Rusudan ISET Policy Institute’s Georgian Reimbursement- Cost Kemularia, Eric Livny, Alexander -

Georgia-Eu International Investors' Conference

GEORGIA-EU INTERNATIONAL INVESTORS' CONFERENCE 13 June, 2014 │ Radisson Blu Iveria Hotel │ Tbilisi, Georgia 09.00-10:00 REGISTRATION; COFFEE/TEA AND BUSINESS EXHIBITION 10:00-11:00 OPENING SESSION (EU-GEORGIA RELATIONS) Welcome remarks and conference overview - H.E. Maia Panjikidze, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia Georgia's AA/DCFTA with the EU: what does it mean for the EU? - H.E. Jose-Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission Georgia's AA/DCFTA with the EU: what does it mean for Georgia? - H.E. Irakli Garibashvili, Prime Minister of Georgia Georgia’s economic outlook and reforms – Giorgi Kvirikashvili, Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia Signing ceremony of the NIF project agreement “Water Infrastructure Modernisation II” 11:00-11:30 BREAK AND BUSINESS EXHIBITION 11:30-13:30 INTEGRATION WITH THE EU AND EXPECTATIONS IN GEORGIA TODAY Moderator: Kakha Gogolashvili, Senior Fellow, Director of EU studies, GFSIS Overview of Georgia's integration with the EU: DCFTA Reform Action Plan: the steps and the needs to be addressed – Mikheil Janelidze, Deputy Minister of Economy and Sustainable Development AA/DCFTAs and the EU acquis – what do they aim to do? – Philippe Cuisson, European Commission, DG TRADE Developing energy links between Georgia and the EU – Peter Mather, Group Vice President BP and President of BP Europe What attracts us to countries which are integrating with the EU? - Constantine Michalos, President of the Union of Hellenic Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Vice-President -

Video-Stream Between Tbilisi and Brussels

Compiled and edited by the NATO Contact Point Embassy (NATO CPE) in Georgia – 10th Edition, December 2013 – IN THIS EDITION : • N A T O – GEORGIA – NATO-GEORGIA COMMISSION AT THE LEVEL OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS MINISTERS – ALLIED FOREIGN MINISTERS PRAISE GEORGIA’S REFORM EFFORTS – MEETING OF THE STATE COMMISSION OF GEORGIA ON NATO INTEGRATION – MOD’S REPORT ON GEORGIA’S NATO INTEGRATION – MEETING OF THE PUBLIC ADVISORY COUNCIL ON GEORGIA’S NATO INTEGRATION • P U B L I C D I P L O M A C Y – WORKSHOP FOR JOURNALISTS: “GEORGIA ON THE NATO MEMBERSHIP PATH” – NATO WORKSHOP FOR COMMUNICATION EXPERTS – 1 st SOUTH CAUCASUS SECURITY FORUM HELD IN TBILISI – JAMIE SHEA ’s VIDEO-CONFERENCE WITH GEORGIAN NGO s – STUDENTS OF THE COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE BRIEFED BY MINISTER PETRIASHVILI – CYBER AND INFORMATION SECURITY SEMINAR IN NATO LIAISON OFFICE – MEETING AT AKAKI TSERETELI KUTAISI STATE UNIVERSITY • N A T O H Q – NATO SECRETARY GENERAL ANNOUNCED DATES FOR 2014 SUMMIT – 2013: NATO’S YEAR IN REVIEW 1 N A T O – GEORGIA NATO-GEORGIA COMMISSION AT THE LEVEL OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS MINISTERS NATO-Georgia Commission at the level of Foreign Affairs Ministers was held in Brussels on 4 December 2013. In his opening remarks, NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen welcomed the meeting and stated the following: “The timing is particularly important, so soon after the inauguration of the new president of Georgia. We have achieved a lot since the NATO-Georgia Commission was created five years ago. We have come closer to fulfilling the promise of the Bucharest that Georgia will become a member of the Alliance. -

![Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1694/georgia-republic-recent-developments-and-u-s-3221694.webp)

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs June 21, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-727 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary The small Black Sea-bordering country of Georgia gained its independence at the end of 1991 with the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The United States had an early interest in its fate, since the well-known former Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, soon became its leader. Democratic and economic reforms faltered during his rule, however. New prospects for the country emerged after Shevardnadze was ousted in 2003 and the U.S.-educated Mikheil Saakashvili was elected president. Then-U.S. President George W. Bush visited Georgia in 2005, and praised the democratic and economic aims of the Saakashvili government while calling on it to deepen reforms. The August 2008 Russia-Georgia conflict caused much damage to Georgia’s economy and military, as well as contributing to hundreds of casualties and tens of thousands of displaced persons in Georgia. The United States quickly pledged $1 billion in humanitarian and recovery assistance for Georgia. In early 2009, the United States and Georgia signed a Strategic Partnership Charter, which pledged U.S. support for democratization, economic development, and security reforms in Georgia. The Obama Administration has provided ongoing support for Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The United States has been Georgia’s largest bilateral aid donor, budgeting cumulative aid of $3.37 billion in FY1992-FY2010 (all agencies and programs). -

My City, Tbilisi

Investor.ge APRIL-MAY 2014 3 Investor.ge Investor.ge CONTENT AmCham Executive Director 6 After Crimea 26 ISO Certification is Not Amy Denman Will the crisis affect Armenia the Same as Performance and its path toward the Improvement Copy Editor Russian-led Customs Union? TBSC Consulting’s Paul Clark Alexander Melin and TemoKhmelidze on 8 The Road to a Free Trade the difference between ISO Marketing & Promotion Agreement with the US Certification and performance Sophia Chakvetadze Georgian Prime Minister improvement. IrakliGharibashvili’s trip Promotional Design to Washington was an 29 Hotel Construction Renews Levan Baratashvili encouraging step for an Building Boom in Tbilisi Magazine Design and Layout eventual FTA. Giorgi Megrelishvili 34 Georgian Entrepreneurs: 10 Fifteen Years of Georgian An interview with Writers Business LashaPapashvili Emil Avdaliani, Helena Bedwell, Paul Investor.ge looks at how the Clark, Maia Edilashvili, Monica Ellena, Georgian economy and doing 36 Reforming Tax Appeals: An ISET, TemoKhmelidze, Nino Patsuria, business in Georgia has Overview of PwC Research on Cordelia Ponczek, Łukasz Ponczek changed. Best Practices for Tax Appeal Councils Photographs 12 The Economic Report Card: A report published as part of Helena Bedwell, Molly Corso, Grading Georgia on its 15- AmCham’s CLT Committee, Monica Ellena, Davit Khizanishvili / year Performance with the support of East-West UNDP Management Institute, Eurasia 16 15 Years and Counting Partnership Foundation, and Special thanks to the AmCham Editorial Heather Yundt interviews USAID. Board and the AmCham staff, as well as three investors and long time ISET and TBSC Consulting. expats on what brought them 38 Brain Drain: Bringing Back to Georgia, how the business the Best environment has changed, and Investor.ge continues its series how their investments have into brain drain with an fared. -

49Th Munich Security Conference

49th Munich Security Conference Friday, 1 February 2013 15:00 - 15:30 WELCOME REMARKS & OPENING STATEMENT Venue: Conference Hall, Hotel Bayerischer Hof Wolfgang Ischinger Ambassador, Chairman, Munich Security Conference, Munich Dr. Thomas de Maizière Federal Minister of Defence, Federal Republic of Germany, Berlin 15:30 - 17:00 Panel Discussion THE EURO CRISIS AND THE FUTURE OF THE EU Venue: Conference Hall, Hotel Bayerischer Hof Chairman: Robert B. Zoellick Former President of The World Bank Group, Washington, D.C. Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble Federal Minister of Finance, Federal Republic of Germany, Berlin Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier Member of the German Bundestag, Chairman of the SPD Parliamentary Group; former Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany, Berlin Anshu Jain Co-Chairman of the Management Board, Deutsche Bank AG, Frankfurt a.M. José Manuel García-Margallo y Marfil Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Spain, Madrid Dr. Dalia Grybauskaitė President, Republic of Lithuania, Vilnius 16:50 A Comment from China Jin Liqun Chairman of the Supervisory Board, China Investment Corporation, Beijing 17:00 - 17:30 Coffee Break Venue: Cocktail Lounge, Hotel Bayerischer Hof 17:30 - 19:00 Panel Discussion THE AMERICAN OIL & GAS BONANZA: THE CHANGING GEOPOLITICS OF ENERGY Venue: Conference Hall, Hotel Bayerischer Hof Dr. Philipp Rösler Federal Minister of Economics and Technology, Federal Republic of Germany, Berlin Günther Oettinger Commissioner for Energy, European Union, Brussels Aleksandr Novak Minister of Energy, Russian Federation, Moscow Jorma Ollila Chairman of the Board of Directors, Royal Dutch Shell, The Hague Carlos Pascual Ambassador, Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs, U.S. -

Relations Between NATO and Georgia Have Deepened Significantly Over

Backgrounder Deepening relations with elations between NATO and Georgia have deepened significantly over the years since dialogue and cooperation was first launched in the early R 1990s. The “Rose Revolution” in 2003 and the push for democratic reforms were a strong catalyst for intensified partnership with the Alliance. Today, Georgia is an aspirant for NATO membership, actively contributes to NATO-led operations, and cooperates with the Allies and other partner coun- tries in many other areas. Georgia’s security policy is based on establishing a secure, democratic, © NATO Georgian Foreign Minister Maia Panjikidze and stable environment. To pursue this goal, it is establishing defence (right) sits next to NATO Secretary General cooperation with partner countries and organisations. Cooperation with Anders Fogh Rasmussen at a meeting of the NATO, active participation in NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme, NATO-Georgia Commission at NATO Headquarters on 5 December 2012. The Allies and eventual accession to the Alliance are central to this policy. encouraged all parties in Georgia to keep up the momentum of the recent elections and to The Allies welcome Georgia’s ambition to join the Alliance and launched consolidate democratic progress. They also an Intensified Dialogue with the country about its membership aspira- thanked Georgia for its substantial contribution to NATO’s mission in Afghanistan. tions in 2006. At the Bucharest Summit in April 2008, Allied leaders agreed that Georgia will become a member of NATO – a decision which Allied leaders reaffirmed at their summit meetings in Strasbourg/Kehl in April 2009, Lisbon in November 2010 and Chicago in May 2012. -

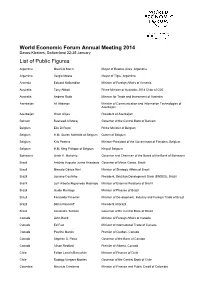

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Rose Revolution”

Georgia’s Identity Making in Relations with Russia and the European Union After the “Rose Revolution” Katrina Urtane, 11041013, ES3-3D Supervisor: Antje Grebner 24/06/2014 Academy of European Studies & Communication Management The Hague University of Applied Sciences Author’s Declaration I confirm that this is my own work and that all sources used have been fully acknowledged and referenced in the prescribed manner Respectfully submitted _____________________ (Date,Signature) Georgia’s Identity Making Katrina Urtane Executive Summary After the “Rose Revolution” in 2003, Georgia’s political elite announced its new policy direction to follow democratic and liberal beliefs norms, values and ideas. This has formed Georgia’s national identity, which, the country claims, has always been European. Georgia’s powerful neighbor country – Russia - never supported those changes and saw them as a threat to the Russian influence in the region. The aim of this thesis is to analyze the impact of Georgia’s national identity reshaping process after the “Rose Revolution” in the relationships between Russia and the European Union, in terms of Georgia’s foreign policy and the perspective of social constructivism. The thesis will also analyze how Georgia’s newly proclaimed democracy is being implemented together with its sustainability and stability. The first chapter is a brief introduction which is followed by the second chapter which includes the literature review. This includes an overview and analysis of the research, substantive findings, theoretical and methodological contributions currently in the field. The third chapter of the work is based on the thesis’ theoretical base, namely, the theory of social constructivism.