“Reading Outside the Comfort Zone”: How Secondary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Comics

9780415606899.c:Layout 1 22/8/10 20:00 Page 1 ISBN 978-0-415-60689-9 90000 9 780415 606899 Adult Comics In a society where a comic equates with knockabout amusement for children, the sudden pre-eminence of adult comics, on everything from political satire to erotic fantasy, has predictably attracted an enormous amount of attention. Adult comics are part of the cultural landscape in a way that would have been unimaginable a decade ago. In this first survey of its kind, Roger Sabin traces the history of comics for older readers from the end of the nineteenth century to the present. He takes in the pioneering titles pre-First World War, the underground 'comix' of the 1960s and 1970s, 'fandom' in the 1970s and 1980s, and the boom of the 1980s and 1990s (including 'graphic novels' and Viz.). Covering comics from the United States, Europe and Japan, Adult Comics addresses such issues as the graphic novel in context, cultural overspill and the role of women. By taking a broad sweep, Sabin demonstrates that the widely-held notion that comics 'grew up' in the late 1980s is a mistaken one, largely invented by the media. Adult Comics: An Introduction is intended primarily for student use, but is written with the comic enthusiast very much in mind. Roger Sabin is a freelance arts journalist, living and working in London. He has written about comics for several national news- papers and magazines, including The Guardian, The Independent and New Statesman and Society. THE NEW ACCENT SERIES General Editor: Terence Hawkes Alternative Shakespeares 1, ed. -

Comic Books: Superheroes/Heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume II: Art, Artifacts, and Material Culture Comic Books: Superheroes/heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images Curriculum Unit 80.02.03 by Patricia Flynn The idea of developing a unit on the American Comic Book grew from the interests and suggestions of middle school students in their art classes. There is a need on the middle school level for an Art History Curriculum that will appeal to young people, and at the same time introduce them to an enduring art form. The history of the American Comic Book seems appropriately qualified to satisfy that need. Art History involves the pursuit of an understanding of man in his time through the study of visual materials. It would seem reasonable to assume that the popular comic book must contain many sources that reflect the values and concerns of the culture that has supported its development and continued growth in America since its introduction in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies , a group of reprinted newspaper comic strips. From my informal discussions with middle school students, three distinctive styles of comic books emerged as possible themes; the superhero and the superheroine, domestic scenes, and animal images. These themes historically repeat themselves in endless variations. The superhero/heroine in the comic book can trace its ancestry back to Greek, Roman and Nordic mythology. Ancient mythologies may be considered as a way of explaining the forces of nature to man. Examples of myths may be found world-wide that describe how the universe began, how men, animals and all living things originated, along with the world’s inanimate natural forces. -

Voice Actor) Next Month Some Reviews, Pictures from ICFA and Wendee Lee (Faye, Cowboy Bebop) Maybe from Some Other Events

Volume 24 Number 10 Issue 292 March 2012 Events A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Megacon was fun but tiring. I got see some people I Knighttrokon really respect and admire. It felt bigger than last year. I heard March 3 from the Slacker and the Man podcast that the long lines from University of Central Florida Student Union previous Megacons were not there this year. Checkout the report $5 per person in this issue. Guests: Kyle Hebert (voice actor) Next month some reviews, pictures from ICFA and Wendee Lee (Faye, Cowboy Bebop) maybe from some other events. knightrokon.com Sun Coast: CGA show (gaming and comics) March 31 Tampa Bay Comic Con Charlotte Harbor Event and Conference Center March 3-4 75 Taylor Street Double Tree Hotel Punta Gorda, Florida 33950 4500 West Cypress Street $8 or $6 with a can of food per person Tampa, FL 33607 $15 per day ICFA 33 (professional conference) Guests: Jim Steranko (comic writer and artist) March 21-25 Mike Grell(comic writer and artist) Orlando Airport Marriott, Orlando, Florida and many more Guest of Honor: China Miéville www.tampabaycomiccon.com/ Guest of Honor: Kelly Link Guest Scholar: Jeffrey Cohen Anime Planet Special Guest Emeritus : Brain Aldiss March 16 www.iafa.org Seminole State College Heathrow Campus Heathrow, Florida 32746 The 2011Nebula Awards nominees $10 entry badge, $15 event pass (source Locus & SFWA website) Edwin Antionio Figueroa III (voice actor) The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America announced theanimeplanet.com the nominees for the 2011 Nebula Awards (presented 2012), the nominees for the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Hatsumi Fair (anime) Presentation, and the nominees for the Andre Norton Award for March 17-18 Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Book. -

West Campus SGA Debate Meet the Candidates Talk Nerdy to Me Presidential Candidate Discusses Important Issues Pg

NEWS OPINION FEATURES SPORTS MEGACON 1 March 30, 2011 VOLUME 15 • ISSUE 13 VALENCIAVOICE.COM West Campus SGA debate Meet the candidates Talk Nerdy to Me Presidential candidate discusses important issues Pg. 4 Shardeh Berry By James Austin Chief-of-staff and VCC student RDV Sportsplex to host West Campus Vice Presidential candidate [email protected] since Fall 2009, said that he wanted sports, and increasing school spirit • Current Parlimentarian of SGA to bring back intramural sports to by holding pep rallies, campus • Platform: The right to vote is one of our West Campus, would work to create competitions and fundraisers to Richer variety of courses for nations founding principles. It gives a mentorship program avalible for support campus clubs. those who can only us, the citizens, the opportunity to Though she is running access one campus make our society better by electing unopposed, the Vice Presidential leaders who we think best represent candidate Berry released her own our thoughts and beliefs. platform that she will be focusing Wendell Smith Jr It’s time again for Valencia’s on in the coming year, including Presidential candidate Student Government elections and encouraging more students to to help the student body make an actively participate in campus • Current Vice President of SGA Playlist Live educated decision the West Campus events. She also wants to focus on • Platform: SGA debates were held on the SSB making more courses available to Increase student participation patio this past Tuesday. all campus’s. Partner with local sportsplex to Pg. 7 host club sports. There were three candidates The power of the people is a scheduled to participate in the guiding light in the politics of this debates. -

The Comic Book and the Korean War

ADVANCINGIN ANOTHERDIRECTION The Comic Book and the Korean War "JUNE,1950! THE INCENDIARY SPARK OF WAR IS- GLOWING IN KOREA! AGAIN AS BEFORE, MEN ARE HUNTING MEN.. .BIAXlNG EACH OTHER TO BITS . COMMITTING WHOLESALE MURDER! THIS, THEN, IS A STORY OF MAN'S INHUMANITY TO MAN! THIS IS A WAR STORY!" th the January-February 1951 issue of E-C Comic's Two- wFisted Tales, the comic book, as it had for WWII five years earlier, followed the United States into the war in Korea. Soon other comic book lines joined E-C in presenting aspects of the new war in Korea. Comic books remain an underutilized popular culture resource in the study of war and yet they provide a very rich part of the tapestry of war and cultural representation. The Korean War comics are also important for their location in the history of the comic book industry. After WWII, the comic industry expanded rapidly, and by the late 1940s comic books entered a boom period with more adults reading comics than ever before. The period between 1935 and 1955 has been characterized as the "Golden Age" of the comic book with over 650 comic book titles appearing monthly during the peak years of popularity in 1953 and 1954 (Nye 239-40). By the late forties, many comics directed the focus away from a primary audience of juveniles and young adolescents to address volatile adult issues in the postwar years, including juvenile delinquency, changing family dynamics, and human sexuality. The emphasis shifted during this period from super heroes like "Superman" to so-called realistic comics that included a great deal of gore, violence, and more "adult" situations. -

British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2013 Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Salisbury, Derek, "Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books" (2013). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 209. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. -

Adult Comics

Adult Comics COMICS and CARDS This is a listing of all Comics rated for Adult viewing. For a listing of General Audience Comics, please refer to the General Audience Comics listing. NOTE: You must be 18 or older to purchase any of the products on this list. Please provide a statement attesting to age with your first order. Title Issue Qty Price Comments Publisher 1001 Arabian Tails 1 3 $18.00 CCP A Cat's Tale 1 0 Guy/guy Angry Viking Press Alice Extreme 3 3 $7.50 Eros Comix 4 5 $7.50 Eros Comix 5 4 $7.50 Eros Comix 6 3 $7.50 Eros Comix 7 4 $7.50 Eros Comix Alice in Sexland 1 0 Eros Comix 2 0 Eros Comix 3 0 Eros Comix 4 0 Eros Comix 5 1 $7.50 Eros Comix 6 0 Eros Comix 7 1 $7.50 Eros Comix 8 0 Eros Comix Amy's Adventures 1 1 $5.00 Radio Comix Anaconda Davida 1 5 $6.00 Radio Comix 2 6 $7.00 Radio Comix Anubis Dark Desire 1 1 $40.00 Radio Comix 2 3 $10.00 Radio Comix 3 3 $8.00 Radio Comix 4 6 $8.00 Radio Comix 30-Jun-19 Page 1 of 24 Title Issue Qty Price Comments Publisher Arizona Funnies 1 8 $6.00 Karno 2 8 $6.00 Karno 3 8 $6.00 Karno 4 9 $6.00 Karno 5 9 $6.00 Karno 6 9 $6.00 Karno Art Worth Stealing 1 0 Jarlidium Press ArtZone with BrainBlackberry 0 Jarlidium Press ArtZone with Megan Giles 0 Jarlidium Press ArtZone with Synnabar 1 $4.00 Jarlidium Press ArtZone with Xianjaguar 0 Jarlidium Press Associated Student Bodies 0 Yearbook (Hardcover); reprints Another Rabco issues 1-8 plus additional artwork 1 1 $25.00 1st Printing Arclight Press 1 1 $20.00 2nd Printing Arclight Press 2 1 $70.00 Arclight Press 3 11 $50.00 Arclight Press 4 7 $30.00 -

2010 1:22 PM Page 1

April 10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 3/18/2010 1:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 10APR 2010 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG Project7:Layout 1 3/15/2010 1:35 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Apr:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/18/2010 2:07 PM Page 1 PREDATORS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUZZARD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN ARROW #1 DC COMICS SUPERMAN #700 DC COMICS JURASSIC PARK: REDEMPTION #1 IDW PUBLISHING HACK/SLASH: MY FIRST MANIAC #1 MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH IMAGE COMICS THE BULLETPROOF COFFIN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD MAGAZINE #226 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #634 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/18/2010 2:14 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS 1 THE ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ #1 G AMAZE INK/ SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS CRITICAL MILLENNIUM #1 G ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC DARKWING DUCK: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS DISNEY‘S ALICE IN WONDERLAND GN/HC G BOOM! STUDIOS RED SONJA #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STARGATE: DANIEL JACKSON #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 GHOSTOPOLIS SC/HC G GRAPHIX THE WHISPERS IN THE WALLS #1 G HUMANOIDS INC STARDROP VOLUME 1 GN G I BOX PUBLISHING KRAZY KAT: A CELEBRATION OF SUNDAYS HC G SUNDAY PRESS BOOKS SIMON & KIRBY SUPERHEROES HC G TITAN PUBLISHING THE PLAYWRIGHT HC G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS CHARMED #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES WILLIAM STOUT: HALLUCINATIONS SC/HC G ART BOOKS 2 SUCK IT, WONDER WOMAN! MISADVENTURES OF A HOLLYWOOD GEEK G HUMOR ASLAN: THE PIN-UP SC G INTERNATIONAL STAR WARS: THE OFFICIAL FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE G STAR WARS TOYFARE #156 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CALENDARS 2 BONE 2011 WALL CALENDAR G COMICS VINTAGE -

Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics As a Screen Based Medium

Dennis Kogel Digital Culture Department of Art and Culture Studies 16.01.2013 MA Thesis Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics as a Screen Based Medium JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanities Art and Culture Studies Tekijä – Author Dennis Kogel Työn nimi – Title Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics as a Screen Based Medium Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Digital Culture MA Thesis Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages January 2013 91 pages Tiivistelmä – Abstract So far, webcomics, or online comics, have been discussed mostly in terms of ideologies of the Internet such as participatory culture or Open Source. Not much thought, however, has been given to webcomics as a new way of making comics that need to be studied in their own right. In this thesis a diverse set of webcomics such as Questionable Content, A Softer World and FreakAngels is analyzed using a combination of N. Katherine Hayles’ Media Specific Analysis (MSA) and the neo-semiotics of comics by Thierry Groensteen. By contrasting print- and web editions of webcomics, as well as looking at web-only webcomics and their methods for structuring and creating stories, this thesis shows that webcomics use the language of comics but build upon it through the technologies of the Web. Far from more sensationalist claims by scholars such as Scott McCloud about webcomics as the future of the comic as a medium, this thesis shows that webcomics need to be understood as a new form of comics that is both constrained and enhanced by Web technologies. Although this thesis cannot be viewed as a complete analysis of the whole of webcomics, it can be used as a starting point for further research in the field and as a showcase of how more traditional areas of academic research such as comic studies can benefit from theories of digital culture. -

Comic Books: Origin, Evolution and Its Reach

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 9, Issue-I, February 2018 ISSN: 0976-8165 Comic Books: Origin, Evolution and Its Reach S Manoj Assistant Professor of English, Agurchand Manmull Jain College (Shift II), Affiliated to the University of Madras Meenambakkam, Chennai 600114. Article History: Submitted-31/01/2018, Revised-06/02/2018, Accepted-08/02/2018, Published-28/02/2018. Abstract: This research article traces the origin of comics and its growth as an art form. It categorizes the different phases of comics and explains the salient features of comics to differentiate it from the other mediums. It also touches on the comic books and its variants around the globe. Keywords: Comics, Origin, Evolution, Popularity, Graphic Novels, Manga series. Origin The earliest known comic book is The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck which was originally published in several languages in Europe in 1837. It was designed by Switzerland's Rodolphe Töpffer, who has been considered in Europe as the creator of the picture story. The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck is 40 pages long and measured 8 ½" x 11". Picture – 1: The first ever comic book, The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck. www.the-criterion.com 246 Comic Books: Origin, Evolution and Its Reach The book was side stitched, and inside there were 6-12 panels per page. -

The Comics Grid. Journal of Comics Scholarship. Year One, Edited by Ernesto Priego (London: the Comics Grid Digital First Editions, 2012)

The Comics Grid Journal of Comics Scholarship Year One Contributor Jeff Albertson James Baker Roberto Bartual Tiago Canário Esther Claudio Jason Dittmer Christophe Dony Kathleen Dunley Jonathan Evans Michael Hill Nicolas Labarre Gabriela Mejan Nina Mickwitz Renata Pascoal s Nicolas Pillai Jesse Prevoo Ernesto Priego Pepo Pérez Jacques Samson Greice Schneider Janine Utell Tony Venezia Compiled by Ernesto Priego Peter Wilkins This page is intentionally blank Journal of Comics Scholarship Year One The Comics Grid Digital First Editions • <http://www.comicsgrid.com/> Contents Citation, Legal Information and License ...............................................................................................6 Foreword. Year One ...................................................................................................................................7 Peanuts, 5 October 1950 ............................................................................................................................8 Ergodic texts: In the Shadow of No Towers ......................................................................................10 The Wrong Place – Brecht Evens .........................................................................................................14 Sin Titulo, by Cameron Stewart, page 1 ...............................................................................................16 Gasoline Alley, 22 April 1934 ............................................................................................................... -

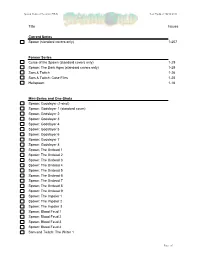

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA)

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Title Issues Current Series Spawn (standard covers only) 1-207 Former Series Curse of the Spawn (standard covers only) 1-29 Spawn: The Dark Ages (standard covers only) 1-28 Sam & Twitch 1-26 Sam & Twitch: Case Files 1-25 Hellspawn 1-16 Mini-Series and One-Shots Spawn: Godslayer (1-shot) Spawn: Godslayer 1 (standard cover) Spawn: Godslayer 2 Spawn: Godslayer 3 Spawn: Godslayer 4 Spawn: Godslayer 5 Spawn: Godslayer 6 Spawn: Godslayer 7 Spawn: Godslayer 8 Spawn: The Undead 1 Spawn: The Undead 2 Spawn: The Undead 3 Spawn: The Undead 4 Spawn: The Undead 5 Spawn: The Undead 6 Spawn: The Undead 7 Spawn: The Undead 8 Spawn: The Undead 9 Spawn: The Impaler 1 Spawn: The Impaler 2 Spawn: The Impaler 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 1 Spawn: Blood Feud 2 Spawn: Blood Feud 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 4 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 1 Page of Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 2 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 3 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 4 Angela 1 Angela 2 Angela 3 Cy-Gor 1 Cy-Gor 2 Cy-Gor 3 Cy-Gor 4 Cy-Gor 5 Cy-Gor 6 Violator 1 Violator 2 Violator 3 Spawn: Blood & Shadows (Annual 1) Spawn Bible (1st Print) Spawn Bible (2nd Print) Spawn Bible (3rd Print) Spawn: Book of Souls Spawn: Blood & Salvation Spawn: Simony Spawn: Architects of Fear The Adventures of Spawn Director’s Cut The Adventures of Spawn 2 Celestine 1 (green) Celestine 1 (purple) Celestine 2 Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (1st Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (2nd Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn)